Abstract

Objective

To determine associations between admission markers of socioeconomic status, transitioning, bridging programme attendance and prior academic preparation on academic outcomes for indigenous Māori, Pacific and rural students admitted into medicine under access pathways designed to widen participation. Findings were compared with students admitted via the general (usual) admission pathway.

Design

Retrospective observational study using secondary data.

Setting

6-year medical programme (MBChB), University of Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. Students are selected and admitted into Year 2 following a first year (undergraduate) or prior degree (graduate).

Participants

1676 domestic students admitted into Year 2 between 2002 and 2012 via three pathways: GENERAL admission (1167), Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme—MAPAS (317) or Rural Origin Medical Preferential Entry—ROMPE (192). Of these, 1082 students completed the programme in the study period.

Main outcome measures

Graduated from medical programme (yes/no), academic scores in Years 2–3 (Grade Point Average (GPA), scored 0–9).

Results

735/778 (95%) of GENERAL, 111/121 (92%) of ROMPE and 146/183 (80%) of MAPAS students graduated from intended programme. The graduation rate was significantly lower in the MAPAS students (p<0.0001). The average Year 2–3 GPA was 6.35 (SD 1.52) for GENERAL, which was higher than 5.82 (SD 1.65, p=0.0013) for ROMPE and 4.33 (SD 1.56, p<0.0001) for MAPAS. Multiple regression analyses identified three key predictors of better academic outcomes: bridging programme attendance, admission as an undergraduate and admission GPA/Grade Point Equivalent (GPE). Attending local urban schools and higher school deciles were also associated with a greater likelihood of graduation. All regression models have controlled for predefined baseline confounders (gender, age and year of admission).

Conclusions

There were varied associations between admission variables and academic outcomes across the three admission pathways. Equity-targeted admission programmes inclusive of variations in academic threshold for entry may support a widening participation agenda, however, additional academic and pastoral supports are recommended.

Keywords: academic outcomes, equity admission, medicine, indigenous, rural

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Most comprehensive quantitative analysis of academic outcomes for equity admission pathways into medicine within New Zealand.

Examines one of the largest cohorts of indigenous medical students available internationally.

Confined to a single medical programme and results may not be generalisable to other programmes or tertiary institutions.

The use of secondary school decile as a proxy for socioeconomic position relies on an area-level indicator of deprivation and may not directly reflect the socioeconomic position of each individual student or their family.

This study did not explore the effect of medical interview outcomes due to different processes of selection being used across equity and general admission pathways.

Introduction

Widening participation in the medical profession remains a priority for many countries worldwide.1 2 Most medical schools acknowledge the need to embrace a widening participation agenda in order to contribute to the development of a health workforce that reflects a community’s ethnic, cultural, geographic and socioeconomic diversity.3 4 Health workforce diversity is expected to reduce inequities in health outcomes through enhanced patient–provider interactions,5 6 increased provision of culturally competent care7 and better delivery to high-need, underserved population groups.8 9 In addition to workforce and healthcare delivery benefits, increasing diversity within medical school classes has been associated with positive effects on the medical school context itself including enhanced educational experiences for all students,10 11 positive student attitudes towards the value of diversity within medicine12 and the creation of learning contexts that challenge stereotypes and reduce implicit bias of medical students towards under-represented minorities.13 Widening participation interventions have been successful at increasing medical school diversity for under-represented ethnic minorities, women and rural students; however, disparities by socioeconomic status remain, as reported in the UK.14 Despite the strong rationale and increasing evidence of effectiveness,4 15 interventions to widen participation, such as medical school quotas, regularly come under attack and are criticised for lowering academic and quality standards.16 17 Comprehensive data analyses that measure outcome differences by admission pathways and attempt to examine the likely predictors for any observed differences are needed.18 This information is expected to better inform the widening participation debate and assist institutions to provide appropriate recruitment and tertiary support interventions for students admitted under equity-targeted admission pathways.

This study explores the predictors of both short-term and long-term academic outcomes for (1) indigenous Māori or Pacific students and (2) rural background students admitted into the medical programme (MBChB) under equity admission pathways, compared with general admission at the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences (FMHS), University of Auckland (UoA) and Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). This is one of two medical schools in NZ, based in a city of over 1.2 million, about one-third of the nation’s population. Entry into the MBChB at UoA may occur in two ways as: (1) an undergraduate within the first year of a health sciences or biomedical sciences degree at the UoA or (2) as a graduate with a completed undergraduate or postgraduate qualification. Both pathways equate to ‘Year 1’ of the MBChB degree at the UoA. The Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme (MAPAS) commenced in 1972 in response to Māori and Pacific health workforce shortages, significant inequities in health outcomes and the indigenous rights of Māori within NZ.19 MAPAS involves comprehensive recruitment and retention interventions delivered within culturally appropriate contexts of support with approximately 240 MAPAS medical students enrolled in 2017 (approximately 20% of the total cohort).19 20 The Rural Origin Medical Preferential Entry (ROMPE) pathway began in 2004, in response to NZ government prioritisation of rural healthcare needs and evidence that students from rural backgrounds are more likely to return to practice in rural regions.21 ROMPE initially offered 20 places to students of rural origin per year.22 The number of places available on each pathway has increased with increasing student class sizes and NZ population proportions. Students may apply for only one pathway. The selection tools used to rank GENERAL and ROMPE students for entry include a measure of prior academic performance (60%), medical entry interview (25%) and score on the Undergraduate Medical and Health Sciences Admission Medical Test (UMAT), an aptitude test (15%). MAPAS selection during the study period consisted of a measure of prior academic performance and an assessment via a MAPAS-specific interview.19

Over the first 20 years of MAPAS (ie, 1972–1992), there was a higher withdrawal rate for MAPAS medical students compared with other students admitted; however, the reasons for these findings are unclear and no associations between likely predictor variables and academic outcomes have been investigated to date.23 We hypothesise that markers of socioeconomic status, transition factors, bridging programme attendance (implemented specifically for Māori and Pacific students aspiring to enter medicine from 1999) and prior academic preparation, are likely to impact on both short-term, that is, Year 2–3 Grade Point Average (GPA) and long-term, that is, graduation outcomes. This study aimed to examine the association between admission variables and academic outcomes for students admitted into the medical programme under equity admission pathways in comparison to those students admitted under the general (usual) admission pathway.

Methods

Study design

A retrospective observational study design was used to analyse data from all domestic students entering Year 2 MBChB at the UoA between 2002 and 2012 (with graduation data inclusive of academic outcomes from 2013). International students were excluded from analysis. Individual student demographic, admission and academic results data were sourced from Student Services Online, the UoA’s web-based centralised student data management system and the Medical Programme Directorate within the FMHS. The study period reflects the availability of electronic data from these sources and the time required for students to have graduated from a 6-year medical programme at the time this study commenced. A Kaupapa Māori Research (KMR) framework, supplemented by Pacific research methodology, was used throughout all aspects including study design, data collection, data analysis and research dissemination.24 25 This approach includes: a commitment to ensuring that the research outputs will have positive benefits for Māori and Pacific participants and communities; an explicit challenge to reject ‘victim blame’ and ‘cultural deficit’ analyses when interpreting data26; and ensuring that any recommendations made from the research aim to facilitate participant academic success. This broad approach is expected to provide benefit for all study participants. The study was approved by the UoA Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC) (Reference 8110).

Predictor variables

Participants were identified by their admission category (MAPAS, ROMPE, GENERAL). The decile rating of secondary school attended was used as a proxy measure of socioeconomic status: low (1–3) (high deprivation), medium (4–7) and high (8–10) (low deprivation).27 28 High decile schools have a high proportion of students who reside in areas of low deprivation (high socioeconomic status). Attended school in Auckland (yes, no) and admitted into Year 1 as a school leaver (SL; yes, no) were used to measure transitioning effects, that is, impact of relocation to Auckland City (the largest city in NZ with a population of 1.4 million where the UoA medical programme is based) and impact of beginning tertiary study as a mature student or SL entrant. SL is defined as enrolment in bachelor level study in the year immediately following secondary school. Completion of a UoA bridging foundation programme (yes, no) that aims to bridge the ‘gaps’ between secondary and tertiary education contexts was recorded. The entry pathway into Year 2 MBChB was recorded as graduate or undergraduate. Academic preparation for medical entry was measured by the GPA or Grade Point Equivalent (GPE) at the time of admission for undergraduate and graduate applicants, respectively (0–9 representing Fail to A+ average grade).

Outcome variables

Two outcome variables were included in this study: graduated from MBChB (yes, no) and MBChB Year 2–3 GPA (0–9). Graduated from MBChB represents a long-term academic outcome and was only applied to those students who completed the MBChB programme by 2013, that is, students admitted between 2002 and 2009. The Year 2–3 GPA represents a short-term academic outcome associated with the 2 preclinical years of the MBChB programme. Data for this measure were available for a larger cohort of current and graduated students, that is, students admitted between 2002 and 2012. The Year 2–3 GPA represents the average GPA achieved across Years 2 and 3 for students admitted between 2002 and 2011, and the GPA achieved across Year 2 only for students admitted in 2012.

Analysis

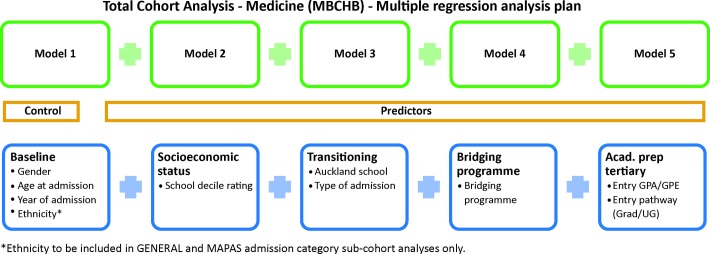

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4. All statistical tests were two sided at a 5% significance level. A full statistical analysis plan was developed a priori that incorporated baseline confounders, key predictor and outcome variables of interest, based on concepts identified from relevant health workforce development and tertiary education literature as well as experience within the FMHS context as to the factors likely to impact on student success (figure 1). Multiple regression analyses with stepwise model selection were used to test the associations between predictor variables and academic outcomes for the total cohort (ie, MAPAS, ROMPE and GENERAL admission combined) and via entry admission subcohorts (ie, MAPAS and GENERAL). The results on ROMPE were not included due to small number of students in the study cohort.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model and multiple regression analysis plan with stepwise model selection (see separate attachment). GPA, Grade Point Average; GPE, Grade Point Equivalent.

The baseline model has controlled for predefined confounders including gender, age and year of admission into Year 2 MBChB (model 1) with the addition of predictor variables representing the sequential effect of socioeconomic status (model 2), transitioning (model 3), bridging programme (model 4) and academic preparation (model 5) on academic outcomes. Each model was initially run with all the prespecified predictors of interest, and those predictors that were significant at the 5% level were retained in the final model. This analysis was applied to all students admitted under MAPAS, ROMPE and GENERAL categories, with the outcome variables assessed at the time of data collection. For MBChB Year 2–3 GPA, the mean difference was reported with 95% CI using the linear regression model. For graduation outcome (yes/no), the OR was reported with 95% CI using logistic regression model. Similar regression analyses were conducted on the two largest subcohorts for MAPAS and GENERAL categories separately, in order to identify significant predictors of academic outcomes specific to that subcohort. Ethnicity was added to the baseline model in the subcohort analyses for MAPAS (Māori, Pacific) and GENERAL (Māori, Pacific, Asian, European/Pākehā, other/missing). Missing data were reported in the descriptive summary, but excluded in final regression analysis.

Results

A total of 1676 students were included in the study, representing 1167 (70%) GENERAL, 317 (19%) MAPAS and 192 (11%) ROMPE admission categories. Cohort demographics are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive variables for GENERAL, MAPAS and ROMPE admission categories 2002–2009

| Descriptive summary variables | Admission category | Total (N=1082) | ||||||||

| GENERAL (n=778) | MAPAS (n=183) | ROMPE (n=121) | ||||||||

| Categorical variables | n | % | n | % | p-Value | n | % | p-Value | n | % |

| Female | 427 | 54.88 | 103 | 56.28 | 0.7319 | 76 | 62.81 | 0.1023 | 606 | 56.01 |

| Ethnicity | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Māori | 20 | 2.57 | 102 | 55.74 | 2 | 1.65 | 124 | 11.46 | ||

| Pacific | 14 | 1.80 | 79 | 43.17 | 2 | 1.65 | 95 | 8.78 | ||

| Asian | 339 | 43.57 | 1 | 0.55 | 12 | 9.92 | 352 | 32.53 | ||

| Other | 44 | 5.66 | 1 | 0.55 | 3 | 2.48 | 48 | 4.44 | ||

| Pākehā/European | 348 | 44.73 | 0 | 0.00 | 99 | 81.82 | 447 | 41.31 | ||

| Missing/no response | 13 | 1.68 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 2.48 | 16 | 1.48 | ||

| School decile rating | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| High | 545 | 70.05 | 80 | 43.72 | 54 | 44.63 | 679 | 62.75 | ||

| Medium | 159 | 20.44 | 54 | 29.51 | 48 | 39.67 | 261 | 24.12 | ||

| Low | 24 | 3.08 | 38 | 20.77 | 9 | 7.44 | 71 | 6.56 | ||

| Missing | 50 | 6.43 | 11 | 6.01 | 10 | 8.26 | 71 | 6.56 | ||

| Attended school in Auckland | 565 | 72.62 | 115 | 62.84 | 0.0017 | 48 | 39.67 | <0.0001 | 728 | 67.28 |

| Completed bridging programme | 8 | 1.03 | 41 | 22.40 | <0.0001 | 1 | 0.83 | 1.0000 | 50 | 4.62 |

| Admitted as school leaver (Year 1) | 565 | 72.62 | 91 | 49.73 | <0.0001 | 78 | 64.46 | 0.0643 | 734 | 67.84 |

| Entry pathway | 0.5200 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Graduate | 121 | 15.55 | 32 | 17.49 | 36 | 29.75 | 189 | 17.47 | ||

| Undergraduate | 657 | 84.45 | 151 | 82.51 | 85 | 70.25 | 893 | 82.53 | ||

| Graduated (yes) | 735 | 94.47 | 146 | 79.78 | <0.0001 | 111 | 91.74 | 0.2343 | 992 | 91.68 |

| Continuous variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age at admission (Year 2) | 20.02 | 3.10 | 20.98 | 3.97 | 0.0014 | 21.07 | 3.80 | 0.0041 | 20.3 | 3.37 |

| Admission GPA/GPE | 8.12 | 0.99 | 6.04 | 1.29 | <0.0001 | 7.72 | 0.88 | 0.0002 | 7.72 | 1.29 |

Cohort 2002–2009 comprises students who matriculated into Year 2 of the MBCHB (or Bachelor of Human Biology BHB) programme within FMHS from 2002 to 2009 inclusive, excluding international entry students. Students who repeated Year 2 have been recorded in their first 2 years. All variables have been compared for the GENERAL versus MAPAS categories and for the General versus RRAS categories. Categorical variables have been tested using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, where necessary. Continuous variables have been tested using the analysis of variance model, with adjustment for multiple comparisons.

GPA, Grade Point Average; GPE, Grade Point Equivalent; MAPAS, Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme; ROMPE, Rural Origin Medical Preferential Entry.

The MAPAS category differs in comparison to the GENERAL category by ethnicity (59% Māori, 41% Pacific, 0.3% Asian, 0.3% other, p<0.0001), school decile (42% high, 34% medium and 20% low, p<0.0001), having attended an Auckland school (60%, p<0.0001) and being admitted into medicine as an SL (50%, p<0.0001). The average admission GPA/GPE was approximately two points lower for MAPAS compared with GENERAL admission category students (6.22, SD 1.19, p<0.0001). The ROMPE category differs in comparison to the GENERAL category by mean age (21.5, SD 4.55, p<0.0001), gender (61.5% female, p<0.017), ethnicity (84% European/Pākehā, 11% Asian, 1% Māori, 1% Pacific, 2% other, p<0.0001), school decile (43% high, 43% medium, 7% low, p<0.0001), having attended an Auckland school (30%, p<0.0001), admission into first year as an SL (59%, p<0.0001) and entry pathway into medicine (31% graduate, 69% undergraduate, p<0.0002). The average admission GPA/GPE was approximately half a point lower for ROMPE compared with GENERAL students (7.74, SD 1.19, p<0.0001).

Of the 1082 students who completed the programme in the study period (ie, admitted between 2002 and 2009), 95% (735/778) of GENERAL, 92% (111/121) of ROMPE and 80% (146/183) of MAPAS students graduated from MBChB. For the total cohort (admitted between 2002 and 2012), the mean Year 2–3 GPA was 6.35 (SD 1.52) for GENERAL, 5.82 (SD 1.65, p=0.0013) for ROMPE and 4.33 (SD 1.56, p<0.0001) for MAPAS students. Table 2 presents the multiple regression analysis findings for the total cohort.

Table 2.

Multiple regression results for Graduated (2002–2009 cohort) and year 2–3 GPA (2002–2012 cohort) academic outcomes

| Model | Predictor variable (ref) | Comparison | Graduated (n=1082) (2002–2009 cohort) |

Year 2–3 GPA (n=1676) (2002–2012 cohort) |

||||

| Overall p-Value | OR | 95% CI | Overall p-Value | Mean difference | 95% CI | |||

| Unadj. | Admission category (GENERAL) | MAPAS | <0.0001 | 0.23 | 0.14 to 0.37 | <0.0001 | −1.93 | −2.11 to 1.76 |

| ROMPE | 0.65 | 0.32 to 1.33 | −0.45 | −0.67 to 0.23 | ||||

| 1 | Admission category (GENERAL) | MAPAS | <0.0001 | 0.24 | 0.14 to 0.39 | <0.0001 | −1.99 | −2.17 to 1.82 |

| ROMPE | 0.70 | 0.33 to 1.50 | −0.54 | −0.76 to 0.32 | ||||

| n=1011* | n=1586* | |||||||

| 2 | Admission category (GENERAL) | MAPAS | 0.0001 | 0.29 | 0.16 to 0.51 | <0.0001 | −1.94 | −2.12 to 1.75 |

| ROMPE | 0.63 | 0.28 to 1.44 | −0.54 | −0.77 to 0.31 | ||||

| School decile (high 8–10) | Medium (4–7) | 0.0032 | 0.56 | 0.32 to 0.98 | 0.0279 | −0.16 | −0.32 to 0.00 | |

| Low (1–3) | 0.29 | 0.14 to 0.61 | −0.32 | −0.61 to 0.03 | ||||

| 3 | Admission category (GENERAL) | MAPAS | 0.0002 | 0.30 | 0.17 to 0.53 | <0.0001 | −1.89 | −2.08 to 1.70 |

| ROMPE | 0.48 | 0.21 to 1.12 | −0.53 | −0.76 to 0.31 | ||||

| School decile (high 8–10) | Medium (4–7) | 0.0022 | 0.52 | 0.29 to 0.93 | 0.0454 | −0.15 | −0.31 0.00 | |

| Low (1–3) | 0.28 | 0.13 to 0.59 | −0.29 | −0.58 to 0.00 | ||||

| Auckland school (yes) | No | 0.0030 | 2.67 | 1.40 to 5.09 | – | – | – | |

| Type of admission (SL) | AA | 0.0430 | 0.53 | 0.29 to 0.10 | 0.0004 | −0.34 | −0.53 to 0.15 | |

| 4 | Admission category (GENERAL) | MAPAS | 0.0182 | 0.44 | 0.23 to 0.84 | <0.0001 | −1.72 | −1.91 to 1.53 |

| ROMPE | 0.42 | 0.18 to 0.10 | −0.61 | −0.83 to 0.39 | ||||

| School decile (high 8–10) | Medium (4–7) | 0.0096 | 0.58 | 0.32 to 1.05 | – | – | – | |

| Low (1–3) | 0.31 | 0.14 to 0.68 | – | – | – | |||

| Auckland school (yes) | No | 0.0062 | 2.52 | 1.30 to 4.88 | – | – | – | |

| Type of admission (SL) | AA | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bridging Programme (no) | Yes | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 0.07 to 0.36 | <0.0001 | −1.24 | −1.56 to 0.91 | |

| 5 | Admission category (GENERAL) | MAPAS | 0.1251 | 1.68 | 0.74 to 3.83 | 0.1306 | 0.10 | −0.10 to 0.31 |

| ROMPE | 0.56 | 0.23 to 1.37 | −0.14 | −0.33 to 0.04 | ||||

| School decile (high 8–10) | Medium (4–7) | 0.0276 | 0.66 | 0.35 to 1.23 | – | – | – | |

| Low (1–3) | 0.31 | 0.13 to 0.74 | – | – | – | |||

| Auckland school (yes) | No | 0.0030 | 2.88 | 1.43 to 5.79 | – | – | – | |

| Type of admission (SL) | AA | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bridging programme (no) | Yes | <0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.07 to 0.40 | <0.0001 | −0.90 | −1.18 to 0.61 | |

| Entry pathway (undergraduate) | Graduate | 0.0100 | 0.45 | 0.24 to 0.82 | <0.0001 | 0.47 | 0.31 to 0.64 | |

| Admission GPA/GPE | Per point increase | <0.0001 | 1.95 | 1.55 to 2.45 | <0.0001 | 0.89 | 0.82 to 0.95 | |

**n is the total number in the cohort, number used is the number of students who have complete data for the given model (all other students are excluded from the analysis). In the total cohort, 90 did not graduate whereas 992 graduated. Models 2–5 cohort sizes reduced to 1011 and 1586, respectively, due to missing school decile data; fewer students were excluded due to missing data for the remaining predictors. Logistic regression model applied to graduation outcome, linear regression model applied to Year 2–3 GPA outcome. All regression models have controlled for year of admission, gender and age at admission. Predefined predictors were added to the baseline model in sequential order to estimate their joint independent effects on the outcome. All models include the predictor Admission Category. Each model was initially run with all the specified predictors, then re-run with stepwise selection to include significant predictors only and obtain final estimates of effect size. Model-adjusted estimates of OR or mean difference (compared with the reference level), 95% CI and associated individual p-values (in symbols) were reported.

AA, alternative admission (ie, non-school leaver); GPA, Grade Point Average; GPE, Grade Point Equivalent; MAPAS, Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme; ROMPE, Rural Origin Medical Preferential Entry; SL, school leaver.

Graduated from medicine

In the unadjusted model, MAPAS students had significantly lower odds of graduating from intended programme compared with GENERAL students (OR: 0.231, 95% CI: 0.144 to 0.371). This pattern remained after controlling for age, gender and year of admission, that is, model 1 (OR: 0.235, CI: 0.143 to 0.386). The odds of MAPAS students graduating in comparison to GENERAL students improved with the addition of medium and low school decile, that is, model 2 (OR: 0.291, CI: 0.165 to 0.513) and having attended a school out of Auckland or being admitted into first year as an SL, that is, model 3 (OR: 0.296, CI: 0.166 to 0.526, p=0.0002). The addition of having attended a bridging programme increased the odds of MAPAS students graduating from medicine by a further 14% in comparison to GENERAL students, that is, model 5 (OR: 0.440, CI: 0.231 to 0.841). When entry pathway into medicine as a graduate and admission GPA/GPE were added to the analysis, that is, model 5, the difference in odds of graduating between admission categories became non-significant (OR: 1.680, CI: 0.736 to 3.833). These findings suggest that attending a higher decile school, a school outside of Auckland and admission into first year as a mature student each make a small contribution to the observed difference in graduation between MAPAS and GENERAL students. However, having attended a bridging/foundation programme prior to medical school entry had a stronger association with improved graduation outcome. In addition, both graduate entry admission and admission GPA/GPE are important contributors, after controlling for which the observed difference between the MAPAS and GENERAL students was no longer statistically significant.

No statistically significant difference was observed in graduation outcome between the ROMPE and GENERAL students when all predictor variables were taken into account, that is, model 5 (OR: 0.558, CI: 0.227 to 1.374).

Year 2–3 GPA

In the unadjusted model, the average Year 2–3 GPA was nearly two points lower for MAPAS compared with GENERAL students (OR: −1.934, CI:−2.112 to −1.756). This pattern remained after controlling for age, gender and year of admission, that is, model 1 (OR: −1.994, CI: −2.169 to −1.819) and school decile, that is, model 2 (OR: −1.936, CI: −2.122 to −1.75). Having attended an Auckland school and being admitted into first year as a mature student reduced the difference in GPA slightly, that is, model 3 (OR: −1.899, CI: −2.076 to −1.702). Having attended a bridging programme prior to medical study further reduced the difference in GPA between MAPAS and GENERAL students, that is, model 4 (OR: −1.724, CI: −1.914 to −1.533). When both graduate entry admission and admission GPA/GPE were added in model 5, no significant difference in Year 2–3 GPA was observed between the admission categories (OR: 0.103, CI: −0.103 to 0.309). These findings suggest that having attended a bridging programme, entering medicine as a graduate and a higher admission GPA/GPE are associated with improved performance for MAPAS compared with GENERAL students in the early years of the medical programme.

In the unadjusted model, the average difference between Year 2–3 GPA was approximately half a point lower for ROMPE compared with GENERAL students (OR: −0.449, CI: −0.668 to −0.23). This general pattern remains for models 1–4. When all predictor variables were taken into account in model 5, the mean difference in Year 2–3 GPA became non-significant (OR: −0.142, CI: −0.326 to 0.043). These findings suggest that admission as a graduate and admission GPA/GPE are the major contributors to the GPA difference between ROMPE and GENERAL students.

Table 3A and B presents the multiple regression analysis findings for the subcohort analyses for the MAPAS and GENERAL cohorts.

Table 3A.

Logistic regression results for Graduated (2002–2009 cohort) academic outcome for MAPAS and GENERAL subgroups

| Model | Predictor variable (ref) | Comparison | Graduated (2002–2009 cohort) MAPAS (n=181) |

Graduated (2002–2009 cohort) GENERAL (n=778) |

||||

| Overall p-Value | OR | 95% CI | Overall p-Value | OR | 95% CI | |||

| 1 | Ethnicity (reference group Māori for MAPAS, Pākehā/European for GENERAL) |

Māori | – | – | – | 0.0010 | 0.175 | 0.047 to 0.648 |

| Pacific | 0.0035 | 0.285 | 0.123 to 0.662 | – | 0.089 | 0.023 to 0.339 | ||

| Asian | – | – | – | – | 0.657 | 0.286 to 1.508 | ||

| Other/missing | – | – | – | – | 0.316 | 0.106 to 0.940 | ||

| 5 | n=170 | n=728 | ||||||

| School decile (high 8–10) | Medium (4–7) | – | – | – | 0.0098 | 0.384 | 0.164 to 0.898 | |

| Low (1–3) | – | – | 0.137 | 0.031 to 0.600 | ||||

| Auckland school (yes) | No | 0.0127 | 4.571 | 1.256 to 16.629 | – | – | – | |

| Type of admission (SL) | AA | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bridging programme (no) | Yes | 0.0014 | 0.141 | 0.042 to 0.468 | – | – | – | |

| Entyr pathway (undergraduate) | Graduate | 0.0123 | 0.170 | 0.043 to 0.681 | – | – | – | |

| Admission GPA/GPE | Per point increase | 0.0319 | 1.758 | 1.050 to 2.994 | <0.0001 | 2.020 | 1.460 to 2.796 | |

Table 3B.

Linear regression results for Year 2–3 GPA (2002–2012 cohort) academic outcome for MAPAS and GENERAL subgroups

| Model | Predictor variable (ref) | Comparison | Year 2–3 GPA (2002– 2012 cohort) MAPAS (n=315) |

Year 2–3 GPA (2002–2012 cohort) GENERAL (n=1167) |

||||

| Overall p-Value | Mean difference | 95% CI | Overall p-value | Mean difference | 95% CI | |||

| 1 | Ethnicity (reference group Māori for MAPAS, Pākehā/European for GENERAL) |

Māori | – | – | – | <0.0001 | −0.616 | −1.201 to to 0.031 |

| Pacific | 0.0109 | −0.425 | −1.018 to 0.168 | – | −2.226 | −2.939 to to 1.513 | ||

| Asian | – | – | – | – | −0.191 | −0.358 to to 0.025 | ||

| Other/missing | – | – | – | – | −0.524 | −0.852 to to 0.196 | ||

| 5 | n=302 | n=1104 | ||||||

| School decile (high 8–10) | Medium (4–7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Low (1–3) | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Auckland school (yes) | No | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Type of admission (SL) | AA | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bridging programme (no) | Yes | <0.0001 | −0.927 | −1.209 to –0.654 | 0.0036 | −1.083 | −1.812 to to 0.355 | |

| Entry pathway (undergraduate) | Graduate | – | – | – | <0.0001 | 0.577 | 0.377 to 0.777 | |

| Admission GPA/GPE | Per point increase | <0.0001 | 0.754 | 0.647 to 0.861 | <0.0001 | 0.977 | 0.891 to 1.063 | |

Logistic regression model has controlled for year of admission, gender and age at admission. Predefined predictors were added to the baseline model in sequential order to estimate their joint independent effects on the outcome. Each model was initially run with all the specified predictors, then rerun with stepwise selection to include significant predictors only and obtain final estimates of effect size. Model-adjusted estimates of ORs (compared with the reference level), 95% CI and associated individual p-values (in symbols) were reported.

AA, alternative admission (ie, non-school leaver); GPA, Grade Point Average; GPE, Grade Point Equivalent; MAPAS, Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme; SL, school leaver.

MAPAS subcohort

After controlling for predefined confounders (eg, gender, age, ethnicity, year of admission) and all significant predictors, that is, model 5, the odds of a MAPAS student graduating from medicine was 86% lower for those MAPAS students who attended a bridging programme versus those who did not (OR: 0.141, CI: 0.042 to 0.468, p=0.0014) and 83% lower for MAPAS students who entered medicine via the graduate pathway versus the undergraduate pathway (OR: 0.170, CI: 0.043 to 0.681, p=0.0123). The odds of graduating increased by 1.8 times for every point increase in admission GPA/GPE (OR:1.758, CI: 1.05 to 2.944, p=0.0319). There were mixed findings for school decile across the models and this variable was not significant in the final model that included admission GPA/GPE and entry pathway.

For MAPAS students, the year 2–3 GPA was similar for students regardless of whether or not they had attended a bridging programme (−0.927, CI: −1.209 to 0.645, p<0.0001) and was 25% higher for every point increase in admission GPA/GPA (0.754, CI: 0.647 to 0.861, p<0.0001). School decile rating was not a significant predictor in the final model for the MAPAS cohort.

GENERAL subcohort

After controlling for predefined confounders (eg, gender, age, ethnicity, year of admission) and all significant predictors, the odds of a GENERAL student graduating from medicine was lower for students who attended a low decile (OR: 0.137, CI: 0.031 to 0.6, p=0.0098) or medium decile school (OR: 0.384, CI: 0.164 to 0.898, p=0.0098) compared with high school decile. Increasing admission GPA/GPE was strongly associated with increased odds of graduating (OR: 2.020, CI: 1.46 to 2.796, p<0.0001). The Year 2–3 GPA was lower for graduate entry GENERAL students compared with undergraduate entry (0.577, CI: 0.377 to 0.777, p=0.0036) with similar outcomes observed for bridging programme attendance (−1.083, CI: −1.182 to −0.355, p=0.0036) and admission GPA/GPE (0.977, CI: 0.891 to 1.063, p=<0.0001). School decile rating was not a significant predictor of early academic outcomes for the GENERAL cohort.

Discussion

This study, based on 1676 medical students over a 10-year period compared outcomes and predictor variables of those admitted via two equity-admission pathways with those in the general admission pathway. To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature describing programme level outcomes to this detail. The descriptive data confirm that it is possible to admit significant numbers of students via these pathways and have most successfully complete the programme. Nearly all students with Māori and Pacific ethnicity entered via the MAPAS pathway. Furthermore, the MAPAS and ROMPE pathways each contained higher proportions of students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and students who attended schools out of Auckland. These findings underscore the importance of having equity pathways or targets, as it unlikely many of the MAPAS students, and some of the ROMPE students would have been successful in the highly competitive selection process for GENERAL students. Furthermore, to provide workforce benefit, students need to complete the programme. Encouragingly, despite marked differences in background and prior performance there was only a 12%–15% difference in the proportion of MAPAS students who graduated in the study period compared with ROMPE or GENERAL admission students respectively. Our hypotheses that markers of socioeconomic status, transitioning factors, bridging programme attendance and academic preparation are likely to impact on both short-term and long-term academic outcomes were confirmed, although findings are mixed within and across the entry pathways. When looking within the MAPAS cohort, the odds of a MAPAS student graduating (compared with another MAPAS student) improved with non-bridging programme attendance and most likely reflect cohort differences in admission GPA/GPE. In contrast, our findings suggest that having attended a bridging programme, entering medicine as an undergraduate and higher admission GPA/GPA are the major contributors to reducing the GPA difference observed between MAPAS and GENERAL students in the early, non-clinical phase of medical training.

This study represents a comprehensive analysis of academic outcomes for equity admission pathways into medicine within NZ. Similarly, this study explores academic outcomes for one of the largest cohorts of indigenous medical students available internationally. We acknowledge that this study was confined to a single medical programme and that the results may not be generalisable to other programmes or tertiary institutions. In particular, the comprehensive nature of the MAPAS programme with respect to student admission and retention support may not be reflected in other tertiary contexts.28 Like similar measures elsewhere (eg, participation of local areas (POLAR) classification in England), the use of secondary school decile as a proxy for socioeconomic position relies on an area-level indicator of deprivation and may not directly reflect the socioeconomic position of each individual student or their family.29 Despite this, other school factors (eg, student attainment, aspirations for future study) have been linked to school decile suggesting that individual students will have been exposed to direct school effects.29–31 This study did not explore the effect of medical interview outcomes due to different processes of selection being used across equity and general admission pathways.32 33 The study period spans across and before periods of significant change within the MAPAS and ROMPE pathways with respect to admissions processes (ie, selection methods and eligibility).19 34 Therefore, study findings should be interpreted cautiously as ‘historical’ markers of equity programme delivery or performance rather than accurate representations of the equity processes in operation today.35

Our findings are consistent with the existing literature base that GPA at the point of admission is the strongest predictor of academic outcomes within the medical programme.32 36–38 In a critical appraisal of studies examining medical school failure, O’Neill and colleagues found that lower entry qualifications at admission were linked to higher failure rates. However, they note that many studies did not control for confounding factors, were mostly focused on student attributes, with few studies examining the role of the institution.39 The fact that 80% of MAPAS students completed medicine despite being admitted with an average GPA approximately two points lower than other medical students is encouraging. This suggests that while GPA at admission is important, other unmeasured factors may be contributing to our findings. Student pastoral and financial issues (likely to be significant for indigenous students given their socioeconomic and demographic profile),40 psychological characteristics,41 student learning styles37 and relevant medical curricula or structural factors39 may also play a role. As noted by Mathers and Parry, graduate applicants to medicine have complex needs arising from their personal social, family and economic circumstances that may affect their academic performance.42 The UoA’s commitment to respond to these student factors (via the provision of comprehensive admission, pastoral and academic support) may be contributing to our outcomes observed, particularly for graduate entry and bridging programme students admitted under MAPAS. The positive effect of bridging programme exposure has also been noted elsewhere.43–47 However within the MAPAS cohort, those students who did not require additional academic support via a bridging programme experienced better academic outcomes. Therefore, our findings reinforce the need for ongoing bridging programme delivery alongside the elimination of educational inequities for Māori and Pacific students (for more information please see https://www.fmhs.auckland.ac.nz/en/faculty/for/future-undergraduates/undergraduate-study-options/certhsc.html).34 48–51 The association between secondary school decile rating (a marker of socioeconomic status and school characteristics) and academic outcomes had mixed results and are unlikely to explain the differences observed by admission pathway. Although school decile has been linked to first year academic outcomes for Māori,52 our findings may reflect the fact that school characteristics have been noted to have less impact on student achievement at the higher end of the achievement scale, that is, GPA ≥4.53 However, the strong association between lower school decile and reduced odds of graduating for the GENERAL admission students challenges this conclusion, differs from other research39 and is of concern.

Our study reinforces the existing evidence that equity-targeted admission programmes, inclusive of variations in academic threshold for entry, can support a widening participation agenda within medicine.4 However, tertiary institutions and society at large must accept that ethnic inequities in educational outcomes and rural workforce development needs should be accounted for within admission pathways and retention support.48 54 Providing comprehensive academic and pastoral assistance to equity admission and lower socioeconomic students who are operating within complex and academically demanding contexts remains paramount.28 55 56 While differences in academic thresholds for equity groups appears necessary, it is often criticised as being ‘politically correct’, providing ‘preferential treatment’ to one group or individual over another and has not been universally welcomed by the public or the profession.16 57–60 Bacchi notes that the framing of widening participation as ‘preferential treatment’ “undermines the legitimacy of the reform and reduces its impact, limiting the kinds of reforms ‘permitted’ and alienating those who are targeted. This undoubtedly serves the interests of those who profit under current social arrangements” (p144).58 Given this context, it is perhaps not surprising that while medical schools strive to increase diversity and meet the goals of a widening participation agenda, successful implementation is influenced by contextual factors associated with institutional leadership, resource allocation and external stakeholder pressure. Razack et al note that while the development of social accountability policy has occurred, medical schools appear to be challenged by the implementation of these policies within student recruitment and selection processes.61 This study responds to calls for open and inclusive discussions in order to advance admissions practice aiming to enhance social justice and widening participation agendas.61

Additional research is warranted (eg, inclusion of secondary school outcomes, non-cognitive testing and medical interview data beyond 2012). Similarly, exploring the effect of institutional attributes should also be considered.37 39 Evidence suggests that tertiary and medical school environments may have different effects on indigenous and ethnic minority students who have reported that their ethnicity adversely affects their medical school experience,62 have described experiences of racism from peers and clinical educators28 63 and are adversely effected by an ‘othering’ medical curriculum that either stereotypes indigenous culture and society or fails to reflect indigenous realities altogether.35 40 64 65 Exploring the impact of these variables on differential academic outcomes for equity admission pathways may require qualitative methods to complement additional quantitative analyses. The impact of a widening participation agenda within medicine must also begin to look beyond the number of students admitted and graduated and extend the analysis to post-graduate clinical contexts including the effect of a diverse health workforce on patient and community outcomes.1 The ultimate aim of equity-targeted admission pathways into medicine is to enhance healthcare delivery, improve health outcomes and eliminate inequities for underserved communities. Understanding when and how this can be achieved remains a challenge for many countries worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank additional members of the Te Hā Advisory Group for the MBChB analysis: Dr Teuila Percival, Dr Vili Nosa, Dr Malakai Ofanoa, Kate Snow, Michelle Chung and Vernon Mogol.

Footnotes

Contributors: EC (senior lecturer medical) is the guarantor of the study; led the study design, methodological approach, interpretation of the data analysis; was the primary author for drafting the manuscript. EW (research assistant) contributed to study design and provided research assistance to obtain and clean data variables; contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript; was responsible for producing the data tables. YJ (senior research fellow) contributed to the study design and provided senior statistical expertise for data analysis; contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. LM (doctoral candidate) provided junior statistical expertise and contributed to the study design and revising the manuscript. RL (professional teaching fellow) contributed to the study design and provided Pacific research methodological expertise in the interpretation of the data and revising of the manuscript. MB (associate dean education) contributed to the study design and provided senior tertiary education expertise in the interpretation of the data, drafting and revising of the manuscript. WB contributed to the study design and provided senior medical education expertise in the interpretation of the data, drafting and revising of the manuscript. PP contributed to the study design and provided senior medical education expertise in the interpretation of the data, drafting and revising of the manuscript. PR (Tumaki, deputy dean Māori) provided senior Māori educational, institutional and Kaupapa Māori expertise and contributed to the study design, drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding: EC was supported by Te Kete Hauora, Ministry of Health (New Zealand) to conduct this research via the provision of a Research Fellowship (contract 414953/337535/00).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the UoA Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC) (reference 8110).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Baxter C, Baxter D, Baxter M. Widening participation in medicine: moving beyond the numbers. Med Educ 2015;49:7–20. 10.1111/medu.12613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Powis D, Hamilton J, McManus IC. Widening access by changing the criteria for selecting medical students. Teach Teach Educ 2007;23:1235–45. 10.1016/j.tate.2007.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cleland JA, Nicholson S, Kelly N, et al. Taking context seriously: explaining widening access policy enactments in UK medical schools. Med Educ 2015;49:25–35. 10.1111/medu.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garlick PB, Brown G. Widening participation in medicine. BMJ 2008;336:1111–3. 10.1136/bmj.39508.606157.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, et al. Delving below the surface. understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(Suppl. 1):S21–S27. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00305.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health 2003;93:248–55. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Emilio Carrillo J, et al. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff 2005;24:499–505. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cantor JC, Miles EL, Baker LC, et al. Physician service to the underserved: implications for affirmative action in medical education. Inquiry 1996;33:167–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Larkins S, Michielsen K, Iputo J, et al. Impact of selection strategies on representation of underserved populations and intention to practise: international findings. Med Educ 2015;49:60–72. 10.1111/medu.12518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, et al. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med 2003;78:460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hung R, McClendon J, Henderson A, et al. Student perspectives on diversity and the cultural climate at a U.S. medical school. Acad Med 2007;82:184–92. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d936a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elam CL, Johnson MM, Wiggs JS, et al. Diversity in medical school: perceptions of first-year students at four southeastern U.S. medical schools. Acad Med 2001;76:60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, et al. Medical School Experiences Associated with Change in Implicit Racial Bias among 3547 students: a Medical Student CHANGES Study Report. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1748–56. 10.1007/s11606-015-3447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seyan K, Greenhalgh T, Dorling D. The standardised admission ratio for measuring widening participation in medical schools: analysis of UK medical school admissions by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sex. BMJ 2004;328:1545–6. 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ready T. The Impact of Affirmative Action on Medical Education and the Nation’s Health : Orfield G, Kurlaender M, Diversity challenges evidence on the impact of Affirmative Action. Cambridge: Harvard Educational Review, 2001:205–19. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ip H, McManus I. Increasing diversity among clinicians. is politically correct but is costly and lacks evidence to support it. Brit Med J 2008;336:1082–3. 10.1136/bmj.39569.609641.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bollinger LC. The need for diversity in higher education. Acad Med 2003;78:431–6. 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Young M, Razack S, Hanson M, et al. Calling for a broader conceptualisation of diversity: surface and deep diversity in four Canadian Medical Schools. Academic Medicine 2012;87:1–10. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826daf74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Curtis E, Reid P. Indigenous Health Workforce Development: challenges and successes of the Vision 20:20 programme. ANZ J Surg 2013;83:49–54. 10.1111/ans.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mitchell CJ, Shulruf B, Poole PJ, et al. Relationship between decile score of secondary school, the size of town of origin and career intentions of New Zealand medical students. J Prim Health Care 2010;2:183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, et al. Critical factors for designing programs to increase the supply and retention of rural primary care physicians. JAMA 2001;286:1041–8. 10.1001/jama.286.9.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitchell CJ, Shulruf B, Poole PJ. Relationship between decile score of secondary school, the size of town of origin and career intentions of New Zealand medical students. J Prim Health Care 2010;2:183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collins JP, White GR. Selection of Auckland medical students over 25 years: a time for change? Med Educ 1993;27:321–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed London & New York: Zed Books, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vaioleti T. Talanoa Research Methodology: a developing position on Pacific Research. Waikato Journal of Education 2006;12:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Valencia R. The evolution of Deficit Thinking: educational Thought and Practice. Washington DC: The Palmer Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mills C, Heyworth J, Rosenwax L, et al. Factors associated with the academic success of first year health science students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009;14:205–17. 10.1007/s10459-008-9103-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Curtis E, Wikaire E, Kool B, et al. What helps and hinders indigenous student success in higher education health programmes: a qualitative study using the critical Incident Technique. Higher Education Research & Development 2015;34:486–500. 10.1080/07294360.2014.973378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Engler R. School leavers’ progression to bachelors-level study. secondary to tertiary transitions. Wellington: Ministry of Education, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thrupp M, Lupton R. Taking school contexts more seriously: the social justice challenge. British Journal of Educational Studies 2006;54:308–28. 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00348.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leach L, Zepke N. Student decision-making by prospective tertiary students. A review of existing New Zealand and overseas literature. Wellington: Ministry of Education, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Poole P, Shulruf B, Rudland J, et al. Comparison of UMAT scores and GPA in prediction of performance in medical school: a national study. Med Educ 2012;46:163–71. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Madjar I, McKinley E, Jenssen S, et al. ; Towards University: navigating NCEA Course Choices in Low-Mid Decile Schools. Auckland: The University of Auckland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Curtis E, Wikaire E, Jiang Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of a Māori and Pacific admission process on first-year health study. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:1–17. 10.1186/s12909-015-0470-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Curtis E, Reid P, Jones R et al. Decolonising the Academy: The process of re-presenting indigenous health in tertiary teaching and learning : Cram F, Phillips H, Sauni P, Māori and Pasifika Higher Education Horizons. Bingley U.K: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2014:147–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilkinson D, Zhang J, Byrne G, et al. Medical school selection criteria and the prediction of academic performance. evidence leading to change in policy and practice at the University of Queensland. Medical Education 2008;188:349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ 2002;324:952–7. 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shulruf B, Poole P, Wang GY, et al. How well do selection tools predict performance later in a medical programme? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2012;17:615–26. 10.1007/s10459-011-9324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Neill LD, Wallstedt B, Eika B, et al. Factors associated with dropout in medical education: a literature review. Med Educ 2011;45:440–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gorinski R, Abernathy G. Māori student retention and success: Curriculum, pedagogy and relationships In: Townsend T, Bates R, eds Handbook of teacher education: globalization, standards and professionalism in times of change. Dordrecht: springer, 2007:229–40. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fazey DMA, Fazey JA. The potential for autonomy in Learning: perceptions of competence, motivation and locus of control in first-year undergraduate students. Studies in Higher Education 2001;26:345–61. 10.1080/03075070120076309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mathers J, Parry J. Older mature students’ experiences of applying to study medicine in England: an interview study. Med Educ 2010;44:1084–94. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burch VC, Sikakana CN, Gunston GD, et al. Generic learning skills in academically-at-risk medical students: a development programme bridges the gap. Med Teach 2013;35:671–7. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.801551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Curtis E, Wikaire E, Jang Y, et al. Open to critique: predictive effects of academic outcomes from a bridging/foundation programme on first-year degree-level study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 2015:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Strayhorn G. A pre-admission program for underrepresented minority and disadvantaged students: application, acceptance, graduation rates and timeliness of graduating from medical school. Acad Med 2000;75:355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Strayhorn G. Participation in a premedical summer program for underrepresented-minority students as a predictor of academic performance in the first three years of medical school: two studies. Acad Med 1999;74:435–47. 10.1097/00001888-199904000-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mathers J, Sitch A, Marsh JL, et al. Widening access to medical education for under-represented socioeconomic groups: population based cross sectional analysis of UK data, 2002-6. BMJ 2011;342:d918 10.1136/bmj.d918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Curtis E, Wikaire E, Stokes K, et al. Addressing indigenous health workforce inequities: a literature review exploring ‘best’ practice for recruitment into tertiary health programmes. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:13–15. 10.1186/1475-9276-11-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ratima M, Brown R, Garrett N, et al. ; Rauringa Raupa: recruitment and retention of Māori in the health and disability workforce. Auckland: taupua Waiora: division of Public Health and Psychosocial Studies. AUT University: Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Anderson I. Indigenous Pathways into the Professions. commissioned Report for the review of higher education access and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Melbourne: University of Melbourne, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Curtis E, Wikaire E, Jiang Y, et al. A tertiary approach to improving equity in health: quantitative analysis of the Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme (MAPAS) process, 2008-2012. Int J Equity Health 2015;14:1–15. 10.1186/s12939-015-0133-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Earle D. Hei titiro anō i te whāinga. Māori achievement in bachelors degrees revisited. Wellington: Ministry of Education, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shulruf B, Hattie J, Tumen S. Individual and school factors affecting students’ participation and success in higher education. Higher Education 2008;56:613–32. 10.1007/s10734-008-9114-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Poole PJ, Moriarty HJ, Wearn AM, et al. Medical student selection in New Zealand: looking to the future. N Z Med J 2009;122:88–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Spencer A, Young T, Williams S, et al. Survey on aboriginal issues within canadian medical programmes. Med Educ 2005;39:1101–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Whiteford G, Shah M, Nair C et al. Equity and excellence are not mutually exclusive: a discussion of academic standards in an era of widening participation. Quality Assurance in Education 2013;21:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Reiter H, Maccoon K. A compromise method to facilitate under-represented minority admissions to medical school. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007;12:223–37. 10.1007/s10459-006-0002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bacchi C. Policy and discourse: challenging the construction of affirmative action as preferential treatment. J Eur Public Policy 2004;11:128–46. 10.1080/1350176042000164334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Reiter H, Maccoon K. A compromise method to facilitate under-represented minority admissions to medical school. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007;12:223–37. 10.1007/s10459-006-0002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mathers J, Sitch A, Marsh J, et al. Widening access to medical education for under-represented economic groups: population based cross sectional analysis of UK data, 2002-6. British Medical Journal 2011;341:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Razack S, Maguire M, Hodges B, et al. What might we be saying to potential applicants to medical school? discourses of excellence, equity, and diversity on the web sites of Canada’s 17 medical schools. Acad Med 2012;87:1323–9. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318267663a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2103–9. 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Garvey G, Rolfe IE, Pearson SA, et al. Indigenous australian medical students’ perceptions of their medical school training. Med Educ 2009;43:1047–55. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chauvel F, Rean J. Doing better for Māori in tertiary settings. Wellington: Tertiary Education Commission, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mayeda DT, Keil M, Dutton HD, et al. “You’ve Gotta Set a Precedent”: Māori and Pacific voices on student success in higher education. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 2014;10:165–79. 10.1177/117718011401000206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.