Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that microbes can influence the efficacy of cancer therapies. By studying colon cancer models, we found that bacteria can metabolize the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine) into its inactive form, 2′,2′-difluorodeoxyuridine. Metabolism was dependent on the expression of a long isoform of the bacterial enzyme cytidine deaminase (CDDL), seen primarily in Gammaproteobacteria. In a colon cancer mouse model, gemcitabine resistance was induced by intra-tumor Gammaproteobacteria, dependent on bacterial CDDL expression, and abrogated by co-treatment with the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. Gemcitabine is commonly used to treat pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and we hypothesized that intra-tumor bacteria might contribute to drug resistance of these tumors. Consistent with this possibility, we found that of the 113 human PDACs that were tested, 86 (76%) were positive for bacteria, mainly Gammaproteobacteria.

Despite substantial advances in cancer treatment, resistance to therapy remains a foremost challenge. Several laboratories have reported that nonmalignant cells in the tumor microenvironment contribute to anti-cancer drug resistance (1–5). For example, resistance to small-molecule RAF inhibitors is conferred by tumor-associated fibroblasts that secret hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (5, 6). Certain non-HGF-secreting fibroblasts can also confer anti-cancer drug resistance. We found that when we co-cultured human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) [isolated from a patient who had undergone skin reduction surgery (table S1)] with colorectal and pancreatic cancer cell lines, the cancer cells were more resistant to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine (figs. S1 and S2) (5). Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analog (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine) used to treat patients with pancreatic, lung, breast, or bladder cancers. Conditioned medium from these fibroblasts was sufficient for the induction of drug resistance, suggesting that resistance was conferred by a secreted factor (Fig. 1A). Resistance was lost, however, when fibroblast-conditioned medium was passed through a 0.45 μm filter (Fig. 1A), suggesting that a very large particle, such as a microbe, may be the mediator of resistance.

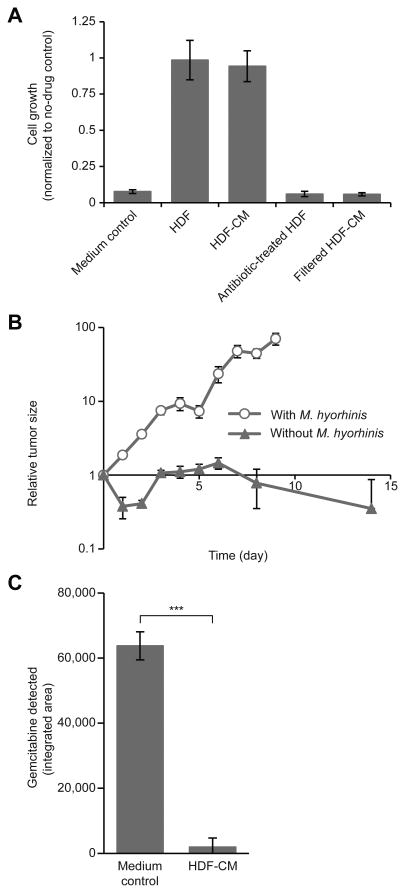

Fig. 1. M. hyorhinis contributes to gemcitabine resistance in colon carcinoma models.

(A) Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled RKO human colorectal carcinoma cells were cultured alone (medium control), with HDFs, HDF-conditioned medium (HDF-CM), HDFs treated with antibiotics (G418) (Supplementary methods), or filtered (0.45 μm) HDF-conditioned medium. Wells were treated with 0.01 μM gemcitabine or with dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) control. The relative proliferation was calculated by normalizing the number of cells (as determined by GFP fluorescence) after 7 days of treatment to the number of cells (GFP) in the DMSO control wells. Bars represent standard deviation between 2 biological replicates, each containing 4 technical replicates. (B) A subcutaneous model of colon carcinoma was generated by injecting M. hyorhinis-positive or -negative luciferase-tagged MC-26 mouse colon carcinoma cells subcutaneously into the flanks of immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Gemcitabine was administered intraperitoneally [150 mg of drug per kg of body weight (mg/kg)] on days 0, 4, and 9. Tumor size was monitored using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) for detection of firefly luciferase activity. Tumor size was normalized to the tumor size on day 0. Bars represent standard error between replicates (N=7 mice in each group). (C) Gemcitabine (0.64μM) was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with HDF-conditioned medium or with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) control. HPLC-MS/MS was used to assess gemcitabine levels at the end of the experiment. Bars represent standard deviation between five biological replicates (P<0.001 by two-tailed paired Student's t test).

Follow-up studies showed that the HDF cells contained Mycoplasma DNA (fig. S3), and whole genome sequencing of HDF-conditioned medium showed that nearly 99% of the reads were attributed to Mycoplasma hyorhinis (table S2). To investigate the possibility of a causal relationship between Mycoplasma and drug-resistance, we treated the Mycoplasma -infected HDF cells with the anti-Mycoplasma antibiotic G418 (Supplementary methods). Antibiotic-treated HDF cells could no longer induce gemcitabine resistance when co-cultured with the RKO colorectal carcinoma cell line (Fig. 1A). To explore whether M. hyorhinis decreases the sensitivity of cancer cells to gemcitabine in vivo, we created a syngeneic cancer mouse model by subcutaneously transplanting M. hyorhinis-positive or -negative MC-26 mouse colon carcinoma cells into the flanks of BALB/c mice. We found that the M. hyorhinis-infected carcinoma cells exhibited gemcitabine resistance in vivo (Fig. 1B).

To study the basis of M. hyorhinis-induced gemcitabine resistance, we incubated gemcitabine with HDF-conditioned medium and analyzed the resulting medium by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). This experiment revealed that conditioned medium from M. hyorhinis-infected HDFs metabolizes gemcitabine into its deaminated inactive metabolite 2′,2′-difluorodeoxyuridine (7) as has been previously reported (8, 9) (Fig. 1C and fig. S4). Furthermore, although antibiotic treatment of HDFs abolished the gemcitabine-metabolizing activity, re-infection of these same HDFs with M. hyorhinis restored gemcitabine metabolism by the cells' conditioned medium (fig. S5).

To determine whether bacteria other than Mycoplasma can confer resistance to gemcitabine, we extended our analysis to 27 bacterial species. Bacteria were incubated with gemcitabine for three hours and then filtered out. The bacteria-free filtrate was added to RKO human colorectal carcinoma cells whose growth was monitored for seven days (Supplementary methods). Thirteen of the 27 species tested eliminated the effect of gemcitabine on RKO human colorectal carcinoma cells, indicating that the resistance mechanism was not restricted to Mycoplasma (table S3).

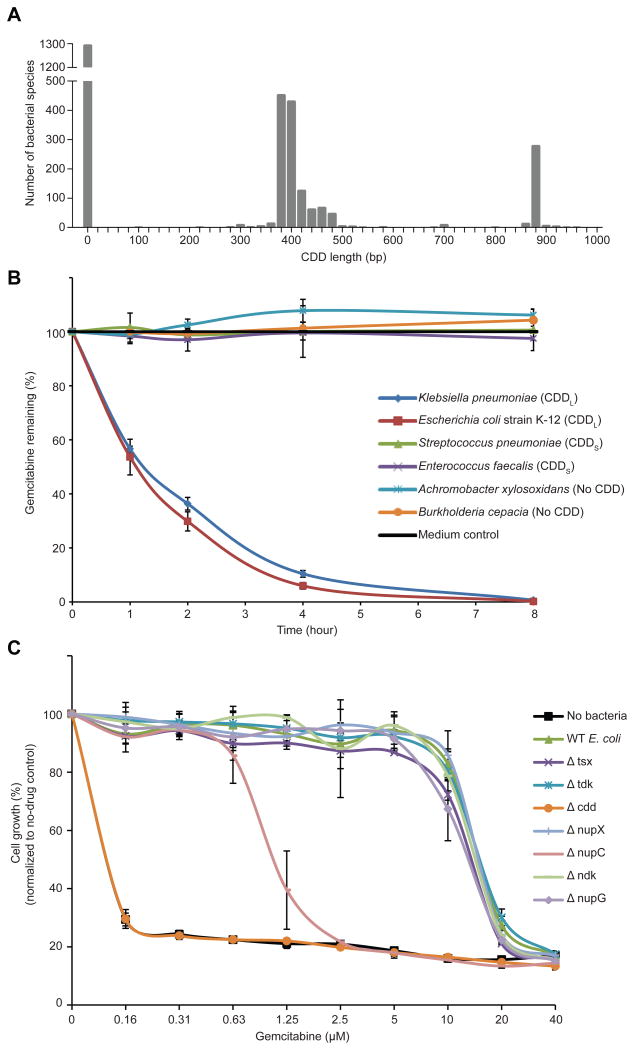

To find the bacterial genes involved in gemcitabine resistance, we first considered the bacterial enzyme cytidine deaminase (CDD) because it was previously shown to mediate gemcitabine deamination by Mycoplasma (8). According to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (10), of 2,674 bacterial species analyzed, 11.4% contained an ∼880-nucleotide long form of CDD (CDDL), 44.4% contained a ∼400-nucleotide short form (CDDS), and 44.2% lacked CDD entirely (Fig. 2A and table S4). 98.4% of the CDDL-containing species belonged to the Gammaproteobacteria class (fig. S6, and table S5).

Fig. 2. The long isoform of bacterial CDD mediates gemcitabine metabolism.

(A) Histogram of CDD DNA sequence length across all bacteria in the KEGG database. bp, base pair (B) Gemcitabine (4 μM) was incubated with 107 bacteria in M9 minimal salts medium. Bacteria were filtered from the media at different time points, and the remaining gemcitabine was detected by HPLC-MS/MS. Bars represent the standard deviation between two biological replicates, each containing two technical repeats. (C) WT (wild-type parental) E. coli strain K-12 (long CDD), CDD knockout (Δ) strains of the parental E. coli, and bacteria-free media were each incubated with different gemcitabine concentrations for 4 hours. Bacteria were then filtered out, and the flow-through media were added to GFP-labeled AsPC1 human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. The growth of AsPC1 cells after 7 days, as measured by GFP, was normalized to a no-drug control. Bars represent standard deviation between 4 replicates.

Next, we examined whether the differential ability of the 27 bacterial species to confer gemcitabine resistance may be explained by the bacteria's specific CDD isoform. We found that all (12/12) species that expressed CDDL conferred resistance, whereas none (0/6) of those lacking CDD and only one (1/9) of those expressing CDDS mediated this effect (table S3). For a subset of these bacteria, we confirmed that the rescue was mediated by gemcitabine metabolism (Fig. 2B and fig. S7). The only bacterium that could confer gemcitabine resistance despite expressing CDDS was M. hyorhinis (table S3). The gemcitabine concentrations used in this experiment had no effect on the in vitro growth of bacteria, regardless of their CDD status (fig. S8). To confirm that CDDL was required for gemcitabine resistance, we tested CDDL-deficient Escherichia coli and found that these bacteria lacked the ability to metabolize gemcitabine (Fig. 2C and figs. S9 and S10). Complementing the CDDL-deficient E. coli with CDDL restored gemcitabine metabolism capability but complementing with CDDS restored gemcitabine metabolism only partially, consistent with our observation that conferring resistance to gemcitabine is preferential to CDDL-containing bacteria (figs. S9 and S10). We also found that in the CDDL-containing E. coli, loss of the nucleoside transporter NupC (11) partially abrogated gemcitabine metabolism (Fig. 2C), presumably reflecting the need for bacteria to internalize the drug before metabolizing it. These findings suggest that certain bacterial species, principally those belonging to the Gammaproteobacteria class (table S5), have the potential to confer CDDL-mediated gemcitabine resistance. We also found that some bacteria conferred resistance to the cancer drug oxaliplatin (fig. S11). Oxaliplatin resistance, however, was not CDDL-mediated, as CDD-deficient bacteria retained the ability to confer resistance to oxaliplatin (fig. S12).

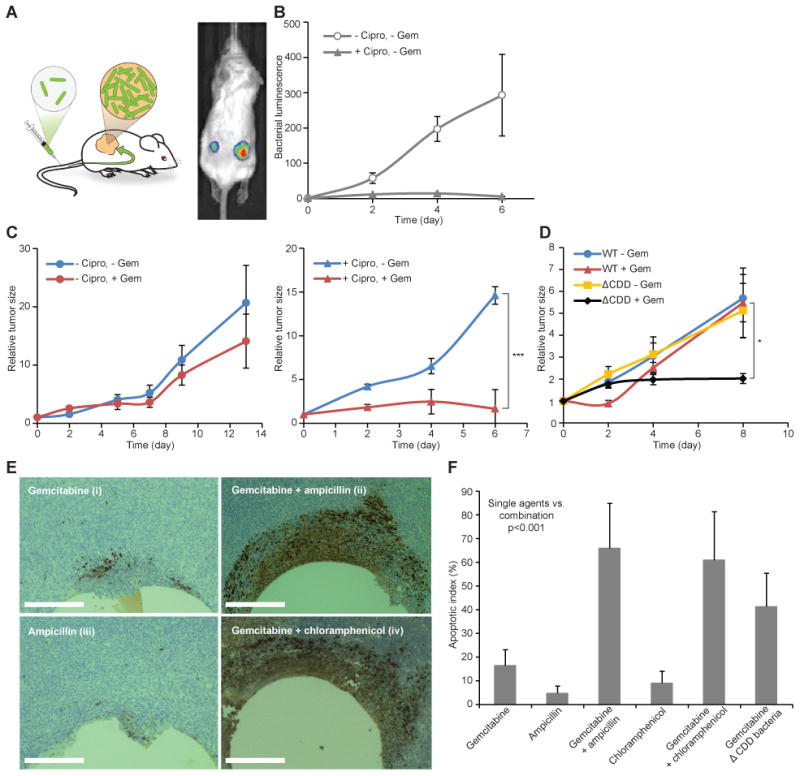

To model the effect of bacterial CDDL expression on gemcitabine efficacy in vivo, we intravenously injected 5×106 E. coli strain Nissle 1917 [previously shown to selectively colonize tumors (12)] into tumor-bearing mice. Bacteria were tagged with luxCDABE luciferase and MC-26 mouse colon carcinoma cells were tagged with firefly luciferase, so that both bacteria and tumor cells could be monitored in vivo through luminescence imaging (Fig. 3A). Mice were then treated with gemcitabine with or without antibiotic (ciprofloxacin) by intraperitoneal injection. In vivo imaging of antibiotic-treated mice confirmed the absence of detectable bacteria, whereas bacteria were detected in control-treated mice (Fig. 3B). Antibiotic-treated mice displayed a marked anti-tumor response to gemcitabine, whereas control-treated mice displayed rapid tumor progression (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3C). As expected, CDD-deficient E. coli failed to induce drug resistance in this model (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Antibiotics enhance the anti-cancer activity of gemcitabine in a mouse model of colon carcinoma.

(A) A subcutaneous model of colon carcinoma (MC-26 cells) was established in immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Bacteria expressing luciferase were injected intravenously and selectively detected in the tumors with IVIS. (B and C) E. coli Nissle 1917 (5×106 bacteria) were injected into the tail vein of mice with MC-26 tumors. The antibiotic ciprofloxacin (Cipro) (150 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (every 12 hours), and gemcitabine (Gem) (150 mg/kg) was administered on days 0 and 4. The antibiotic prevented bacterial growth (B) and increased the efficacy of the chemotherapy [(C) Left panel, no significant difference; right panel, ***P<0.001 by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni adjustment]. N=16 to 18 mice (groups without Cipro) and 9 to 13 mice (groups with Cipro). Tumor size was normalized to the tumor size on day 0. Bars represent standard error of the mean. (D) WT E. coli or CDD-deficient E. coli (ΔCDD) were injected into the tail vein of mice with MC-26 tumors. Gemcitabine was administered intraperitoneally (150mg/kg) on days 0 and 4. Gemcitabine significantly inhibited tumor growth when ΔCDD bacteria rather than WT bacteria were administered (*P<0.05 by two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni adjustment). N=15 mice (WT –Gem), 6 to 8 mice (WT +Gem), 10 mice (ΔCDD –Gem), and 4 to 6 mice (ΔCDD +Gem). Tumor size was normalized to the tumor size on day 0. Bars represent standard error of the mean. (E) Devices for local intra-tumor release of drug microdoses were used to release gemcitabine and antibiotics, alone and in combination, directly into the microenvironment of bacteria-colonized tumors to assess in vivo efficacy (13). Histological staining by cleaved caspase 3 shows significantly more apoptosis when gemcitabine is released in combination with antibiotics (ii and iv) but less apoptosis when gemcitabine (i) or ampicillin (iii) is administrated alone. Scale bars, 200 μm. (F) Graph comparing the percentage of apoptotic cells in tumor regions near reservoirs containing the treatment agents (gemcitabine and/or antibiotics). The increase in apoptosis achieved by delivering gemcitabine with antibiotics compared to delivering gemcitabine or antibiotics alone is statistically significant (P <0.001, Student's t test). N=8 mice per treatment group.

To exclude the possibility that the bacteria-mediated resistance observed in vivo was achieved through systemic exposure of bacteria to the drug (e.g., in the peritoneum or in blood), we used an implantable microdevice capable of local gemcitabine delivery, with or without antibiotic, directly into the tumor, allowing each tumor to serve as its own control (13). Histological staining for cleaved caspase-3, a marker of tumor cell apoptosis, revealed that there was significantly more apoptosis when gemcitabine was delivered in combination with antibiotic than when either agent was delivered alone (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3, E and F).

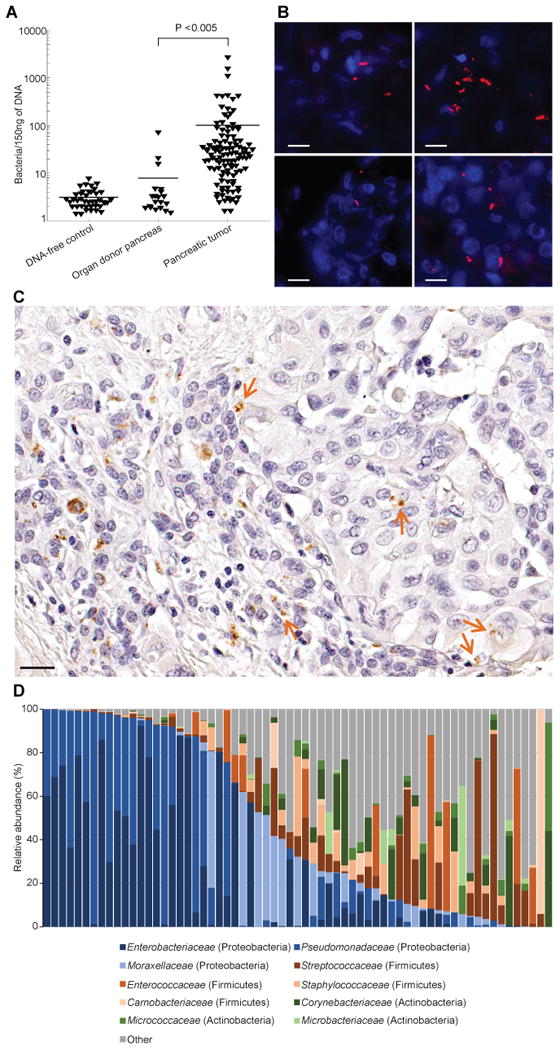

We next examined whether bacteria are present within the microenvironment of human tumors. We focused on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) because of the central role of gemcitabine in the treatment of patients with this type of cancer. Human PDAC samples (N=113) obtained during pancreatic cancer surgery were first analyzed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to detect bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA). Particular attention was paid to maintaining sterile technique and to using methods optimized for bacterial DNA extraction (14). As a control, we evaluated 20 samples from normal human pancreas, obtained from organ donors. Bacterial DNA was detected in 86/113 (76%) PDAC samples and in only 3/20 (15%) normal pancreas controls (P < 0.005) (Fig. 4A, fig. S13 and table S6). Assuming a mass of 8pg of DNA per cancer cell, we estimated that bacteria-colonized PDAC samples had an average of one bacterium per 146 human cells [95% confidence interval (CI) = 53 to 201 cells]. To confirm the presence of bacteria within tumors using non-PCR-based methods, we performed ribosomal RNA (rRNA) fluorescence in situ hybridization, using probes targeting bacterial 16S rRNA (15), and immunohistochemistry, using an anti-bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antibody. These approaches confirmed the presence of intra-tumor bacteria in human PDAC samples (Fig. 4, B and C and figs. S14-S16).

Fig. 4. Characterization of bacteria in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas.

(A) The presence of bacteria in human pancreatic tumors or in healthy pancreatic tissue from organ donors was assessed by bacterial 16S rDNA qPCR. A calibration curve, generated by spiking bacterial DNA into human DNA, was used to estimate bacterial numbers (fig. S13). Bars represent the mean. (B) Fluorescence in situ hybridization was used to detect bacterial 16S rRNA sequences in a human PDAC tumor (red). Cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). Four sections from one tumor are presented. Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Immunohistochemistry of a human PDAC tumor using an anti-bacterial LPS antibody. Arrows point to LPS staining in the tumor tissue. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Distribution of family-level phylotypes in 65 human PDAC tumors. Relative abundance (%) is plotted for each tumor.

To determine which bacteria were present in these human PDAC samples, we performed deep sequencing of PCR-amplified bacterial 16S rDNA on 65 out of the 113 PDAC tumors. The most common species identified (comprising 51.7% of all reads) belong to the class Gammaproteobacteria; most are members of the Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonadaceae families (Fig. 4D, fig. S17 and table S7). Proteobacteria are abundant in the duodenum (16, 17), to which the pancreatic duct opens, suggesting that retrograde bacterial migration from the duodenum to the pancreas could be a source of PDAC-associated bacteria. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed that patients who underwent instrumentation of the pancreatic duct had significantly more bacteria in their tumors than did those who did not undergo instrumentation (P < 0.05 by the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test, table S6). Note that Enterobacteriaceae express CDDL (table S5), consistent with the possibility that these bacteria contribute to gemcitabine resistance. To confirm that bacteria derived from human PDAC can mediate gemcitabine resistance, we cultured bacteria from 15 fresh human PDAC tumors and found that 14/15 (93%) rendered the RKO and HCT116 human colon carcinoma cell lines fully resistant to gemcitabine (fig. S18).

Collectively, our results indicate that PDACs contain bacteria that can potentially modulate tumor sensitivity to gemcitabine. Earlier studies on the association between bacteria and cancer have focused primarily on exploring (i) the role of bacteria in tumor pathogenesis, (ii) the potential of gut bacteria to modulate anti-tumor immune responses (18, 19), and (iii) the contribution of bacterial metabolism to the adverse effects of chemotherapy (20). Here we demonstrate that bacteria are a component of the PDAC tumor microenvironment. Regardless of whether bacteria are involved in tumor pathogenesis or exist as opportunistic residents (21), they may play a critical role in mediating resistance to chemotherapy. In contrast to other mechanisms that affect the half-life of anti-cancer drugs (such as liver-expressed drug-metabolizing enzymes), the presence of bacteria in human tumors may paradoxically result in drug concentrations that are lower in the tumor than in other organs. This resistance mechanism is also distinct from a recent report of bacteria conferring drug resistance by the induction of tumor cell autophagy in colorectal cancer (22). Our observation that anti-tumor drug responses can be potentiated by co-administration of antibiotics suggests that such combinations merit additional exploration in the pre-clinical and clinical setting. The potential effect of intra-tumor bacteria on tumor immunity also deserves exploration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.S. is funded by the ISRAEL SCIENCE FOUNDATION (grant No. 1877/14), the Moross Integrated Cancer Center, the Fabrikant-Morse Families Research Fund for Humanity, the Hymen T. Milgrom Trust, Rising Tide Foundation, the Dr. Dvora and Haim Teitelbaum Endowment Fund, the Tobias and Toni Gottesfeld Scholarship, and by Prof. Amnon Shashua, Israel. Dr. Straussman is the incumbent of the Roel C. Buck Career Development Chair. T.R.G. is funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by the United States National Cancer Institute (grant # U54CA112962). C.H. is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Evelo Biosciences. J.A.W is a paid advisor for GlaxoSmithKline, Roche/Genentech, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

References and Notes

- 1.Klemm F, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of therapeutic response in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topalian SL, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frese KK, et al. nab-Paclitaxel potentiates gemcitabine activity by reducing cytidine deaminase levels in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:260–269. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feig C, et al. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straussman R, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson TR, et al. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plunkett W, et al. Gemcitabine: metabolism, mechanisms of action, and self-potentiation. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vande Voorde J, et al. Nucleoside-catabolizing enzymes in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures compromise the cytostatic activity of the anticancer drug gemcitabine. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:13054–13065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehouritis P, et al. Local bacteria affect the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14554. doi: 10.1038/srep14554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig JE, Zhang Y, Gallagher MP. Cloning of the nupC gene of Escherichia coli encoding a nucleoside transport system, and identification of an adjacent insertion element, IS 186. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1159–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stritzker J, et al. Tumor-specific colonization, tissue distribution, and gene induction by probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in live mice. Int J Med Microbiol IJMM. 2007;297:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonas O, et al. An implantable microdevice to perform high-throughput in vivo drug sensitivity testing in tumors. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:1–11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan S, Cohen DB, Ravel J, Abdo Z, Forney LJ. Evaluation of methods for the extraction and purification of DNA from the human microbiome. PloS One. 2012;7:e33865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyubimova A, et al. Single-molecule mRNA detection and counting in mammalian tissue. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1743–1758. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nistal E, et al. Differences of small intestinal bacteria populations in adults and children with/without celiac disease: effect of age, gluten diet, and disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:649–656. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ou G, et al. Proximal small intestinal microbiota and identification of rod-shaped bacteria associated with childhood celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3058–3067. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivan A, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350:1084–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vétizou M, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015;350:1079–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace BD, et al. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science. 2010;330:831–835. doi: 10.1126/science.1191175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummins J, Tangney M. Bacteria and tumours: causative agents or opportunistic inhabitants? Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu T, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell. 2017;170:548–563.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danino T, et al. Programmable probiotics for detection of cancer in urine. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:1–15. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caporaso JG, et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald D, et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012;6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knights D, et al. Supervised classification of microbiota mitigates mislabeling errors. ISME J. 2011;5:570–573. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knights D, et al. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nat Methods. 2011;8:761–763. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.