Abstract

Background

Infantile gangliosidoses include GM1 gangliosidosis and GM2 gangliosidosis (Tay-Sachs disease, Sandhoff disease). To date, natural history studies in infantile GM2 (iGM2) have been retrospective and conducted through surveys. Compared to iGM2, there is even less natural history information available on infantile GM1 disease (iGM1). There are no approved treatments for infantile gangliosidoses. Substrate reduction therapy using miglustat has been tried, but is limited by gastrointestinal side effects. Development of effective treatments will require identification of meaningful outcomes in the setting of rapidly progressive and fatal diseases.

Objectives

This study aimed to establish a timeline of clinical changes occurring in infantile gangliosidoses, prospectively, to: 1) characterize the natural history of these diseases; 2) improve planning of clinical care; and 3) identify meaningful future treatment outcome measures.

Methods

Patients were evaluated prospectively through ongoing clinical care.

Results

Twenty-three patients were evaluated: 8 infantile GM1, 9 infantile Tay-Sachs disease, 6 infantile Sandhoff disease. Common patterns of clinical change included: hypotonia before 6 months of age; severe motor skill impairment within first year of life; seizures; dysphagia and feeding-tube placement before 18 months of age. Neurodevelopmental testing scores reached the floor of the testing scale by 20 to 28 months of age. Vertebral beaking, kyphosis, and scoliosis were unique to patients with infantile GM1. Chest physiotherapy was associated with increased survival in iGM1 (p=0.0056). Miglustat combined with a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (the Syner-G regimen) in patients who received a feeding-tube was associated with increased survival in infantile GM1 (p=0.025).

Conclusions

This is the first prospective study of the natural history of infantile gangliosidoses and the very first natural history of infantile GM1. The homogeneity of the infantile gangliosidoses phenotype as demonstrated by the clinical events timeline in this study provides promising secondary outcome measure candidates. This study indicates that overall survival is a meaningful primary outcome measure for future clinical trials due to reliable timing and early occurrence of this event. Combination therapy approaches, instead of monotherapy approaches, will likely be the best way to optimize clinical outcomes. Combination therapy approaches include palliative therapies (e.g., chest physiotherapy) along with treatments that address the underlying disease pathology (e.g. miglustat or future gene therapies).

Keywords: disaccharidase, gangliosidosis, ganglioside, ketogenic diet, substrate, miglustat

1.0 Introduction

The gangliosidosis diseases are inherited metabolic diseases in which accumulation of ganglioside (glycosphingolipids containing one or more sialic acids) in the central nervous system (CNS) leads to severe and progressive neurological impairment [1,2].

GM1 gangliosidosis is caused by mutations in the GLB1 gene, resulting in deficiency of β-galactosidase and subsequent accumulation of GM1 ganglioside [1,2]. The GM2 gangliosidoses, Tay-Sachs disease and Sandhoff disease, are caused by mutations in the HEXA and HEXB genes encoding the α and β subunits, respectively, of β-hexosaminidase A, resulting in accumulation of GM2 ganglioside [1,2].

Phenotypes of GM1 and GM2 gangliosidoses have been described as infantile, juvenile, and late-onset. In the infantile phenotype, the onset of symptoms manifest during infancy. The disease course includes progressive neurological impairment and death in early childhood [1–5]. To date, natural history studies in infantile GM2 (iGM2) are based on retrospective data collected through surveys [1–5]. Although case reports exist for infantile GM1 gangliosidosis (iGM1), no prospective natural history studies have been conducted [5].

The onset of symptoms in the juvenile forms of GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis are recognized between the third and fifth year of life, with both diseases commonly presenting with ataxia and progressing with development of dysarthria, dysphagia, and hypotonia [1,2,4–6]. Seizures may occur early on, or later in the disease course. Age of death in the juvenile form varies and may occur in late childhood before onset of adolescence, or may occur during or after adolescence, with some children living well into their teenage years or early adulthood [1,2,4–6]. A late-infantile phenotype for GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis has also been described, in which symptoms are first noted between 1 and 3 years of age, and with lifespan extending into later childhood [1,2,5,7]. In contrast to the childhood forms, the late-onset, or chronic adult forms of gangliosidoses have symptoms presenting in early or mid-adulthood, often exhibiting as limb-girdle weakness, followed by development of ataxia and progressive neuromuscular weakness, with eventual loss of ability to ambulate independently [1,2,5–10]. Difficulties with speech may develop and psychiatric changes may occur [1,2,5,6]. Severe physical disability may develop while the patient is a young adult, but in some patients severe disability is not present until the 4th or 5th decade of life [1,2,5,6]. Long-term survival in the late-onset phenotype varies greatly [1,2,5,6].

There are no approved treatments for the gangliosidoses. Research is underway in animal models evaluating gene therapy technologies and intravenous enzyme replacement therapies (ERT) [5,11]. Palliative care approaches for patients with gangliosidoses, meanwhile, continue to improve. Bley, et al found that median survival in iGM2 has increased during the past 50 years, and this is attributed largely to palliative care, especially feeding-tube placement [3].

The most highly recognized barrier to therapy development is finding treatments that have adequate bioavailability in the central nervous system (CNS). Substrate reduction therapy using miglustat has been tried in the infantile gangliosidosis patient population (both GM1 and GM2 gangliosidoses) [5,12–14]. Although miglustat is known to cross the blood-brain barrier, has been generally well tolerated, and has demonstrated safety in this population, it has not been observed to result in marked improvement in symptom management or disease progression [5,12–14]. Gastrointestinal side effects due to miglustat’s inhibition of disaccharidases in the gut were dose-limiting in these studies. The impact of this dose-limitation on clinical outcomes in these studies is unknown, but resulted in the need to lower the miglustat dose or discontinue miglustat in some of the patients [5,12–13]. The gastrointestinal side effects of miglustat may be mitigated with a low-carbohydrate diet [15]. Safety of low-carbohydrate diets in an infantile patient group, however, may be of concern in terms of maintaining adequate nutrition.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats indicate that only about 25–40% of the miglustat dose reaches the brain tissue [16]. A study in adult Sandhoff disease mice showed that the combination of a restricted ketogenic diet and miglustat resulted in a significant reduction of GM2 ganglioside in the forebrain, and a 3.5-fold accumulation of miglustat in the cortex, compared to mice receiving a standard diet and taking miglustat [17]. Thus the 3.5-fold higher cortex concentration of miglustat when given in combination with a ketogenic diet represents a possible synergy for potentially achieving a higher bioavailability of miglustat to the CNS.

Another barrier to treatment development is identifying meaningful outcome measures of clinical response with which to evaluate therapies. Lack of reliable, valid, and responsive outcome measures can lead to delays in bringing promising treatments through clinical trials and to an eventual licensed therapy status [18].

1.1 Objectives

This study aimed to prospectively characterize, for the first time, a timeline of clinical changes occurring in infantile gangliosidoses, with the following goals: 1) better characterize the natural history of these diseases; 2) improve clinical care planning ability of parents and clinicians; and 3) identify meaningful future treatment outcome measures in the setting of a rapidly progressive fatal disease.

2.0 Materials and Methods

This study was conducted under clinical trials (NCT00668187 and NCT02030015) of the Lysosomal Disease Network (U54NS065768) which is a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). It was conducted at the University of Minnesota, with IRB approval and IRB-approved parental consent. Patients were enrolled in a natural history study in which clinical events were documented prospectively while patients were receiving clinical care. As part of clinical care, some patients were placed on a combination regimen, called Syner-G, which consists of miglustat and a very low carbohydrate diet, the ketogenic diet. The goal of this combination therapy was to maximize miglustat safety and tolerability, while lowering risk of dose-limiting gastrointestinal side effects of miglustat. The parents of patients using Syner-G therapy were given the opportunity to consent to sharing the patient’s experience on Syner-G in the medical literature and with the scientific community.

The approach in this research project was unique because the data for both the natural history study as well as Syner-G was obtained through clinical care. Standard clinical care included visits with providers at the University of Minnesota a minimum of once yearly. Clinical evaluations were performed by specialists in lysosomal diseases which include the following: metabolic geneticist, genetic counselor, pharmacotherapist, neurologist, cardiologist, and pediatric psychologist. The number of different providers the patient could see was dependent upon medical insurance coverage. All patients were also followed by providers near their homes, including a neurologist, geneticist and primary care physician. Patients receiving Syner-G were followed by a ketogenic dietician near the patient’s home, and the ketogenic diet clinical monitoring was done according to the local institution’s policies.

Follow-up telephone communications with the parents were made a minimum of once every 6 months and were conducted by a pharmacotherapist or clinical geneticist. These communications queried about onset of new clinical symptoms and changes in existing symptoms. For patients using Syner-G, compliance and tolerance were assessed by communication with the parents and the ketogenic dietician. This communication was weekly during the first two months patients were transitioning to Syner-G; then were done a minimum of every three months thereafter.

Neurodevelopmental evaluations were completed using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development®, Third Edition (Bayley-III®), a well-normed and validated, examiner-administered evaluation of cognition, language, and motor skills for children from birth to 42-months-old [19]. Measures standardized for children older than 42 months were not appropriate for this study’s participants’ level of functioning. The Bayley-III® was administered to all participants receiving neurodevelopmental evaluations, regardless of their chronological age. To determine functioning outside of the evaluation session, caregivers completed the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (Vineland™-II) [20]. This measure is standardized for individuals from birth to 90-years-old and assesses domains including functional communication, daily living skills, social skills, and motor skills [20].

Clinical changes in the patient’s status and clinical interventions were recorded and a timeline of these changes and interventions for each patient was mapped. Clinical changes were defined as changes that required an intervention in order to improve or maintain the health of the patient. Six-month intervals were used to summarize the timing of events for all the patients, corresponding with the minimal frequency of follow-up by study staff with patients’ caregivers.

Patients were not excluded if they were using experimental or alternative treatments, or palliative therapies. Alternative and palliative therapies were recorded. For patients using Syner-G therapy, the ketogenic diet was administered at a 4:1 ratio or a 2.5:1 – 3:1 ratio, if the patient did not tolerate a 4:1 ratio. Miglustat was dosed according to guidelines that are used for patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C for children less than 12 years old [21]. The miglustat dosing according to this guideline is as follows: 100 mg once daily for Body Surface Area (BSA) ≤0.47 m2; 100 mg twice daily for BSA >0.47–0.73 m2; 100 mg three times daily for BSA >0.73–0.88 m2; 200 mg twice daily for BSA >0.88–1.25 m2 ; 200 mg three times daily for BSA >1.25 m2 [21].

2.1 Statistical Analysis

Overall survival curves between infantile GM1 and infantile GM2 were compared using log-rank test. A Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the differences in the age of onset of clinical changes and the age that motor skills changes were observed between infantile GM1 and infantile GM2. A Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare the differences between infantile GM1 and infantile GM2 in the median age of onset of clinical changes and the age that motor skills changes occurred.

3.0 Results

Twenty-three patients were enrolled in the study: 8 with infantile GM1 gangliosidosis (iGM1), 15 with infantile GM2 gangliosidosis (iGM2), which comprised 9 with infantile Tay-Sachs disease (iTS) and 6 with infantile Sandhoff disease (iSD). Fifteen patients were female (iGM1 = 5, iGM2 = 10) and 8 were male (iGM1 = 3, iGM2 = 5). Irish and French Canadian were common races in both iGM1 and iGM2 patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Table

| Patient Characteristics | Diagnostic Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Gender | Race (per medical record) | Genotype | Age at clinical finding (months) | Initial clinical finding leading to diagnosis | Age at diagnosis (months) |

| GM1 | F | White | p.R68W/int1 5195ins T | 6 | Not sitting unsupported | 12 |

| GM1 | M | Irish, English, Native American, German | p.K578R/c.75+2dupT | 0.25 | Difficulty latching on and sucking from natural and artificial nipples | 10 |

| GM1 | M | N/A | N/A | 5 | Unable to sit up or roll over. Not making efforts to focus eyes on things and people | 11 |

| GM1 | F | Asian, White | c.1480-2A>G/p.N318D | 0 | Placental vacuolization | 0 |

| GM1 | F | Irish, Portugese, German, English | c.377T>C Partial deletion, extent of deletion undetermined | 0 | Extended, possibly opisthotonic posture | 13 |

| GM1 | F | White | c.442C>T/c.1321G>A | 0 | Placental vacuolization | 1 |

| GM1 | M | White | c.808T>G/c.841C>T | 0 | Not focusing on mom’s face and disinterested in life | 7 |

| GM1 | F | French Canadian, Irish, German, Swedish, Dutch, Italian, Russian, Polish | c.699delG/c.1733A>G | 3 | Noisy breathing due to GI reflux | 15 |

| Tay-Sachs | F | Irish, British, Swedish, North European Caucasian | c.929_930delCT/c.1073+1G>A | 6 | Not sitting unsupported | 15 |

| Tay-Sachs | M | Irish, English, Mexican, Polish, French, European | c.508C>/c.929_930delCT | 0.5 | GERD at 2 weeks and not crawling at 6 months | 15 |

| Tay-Sachs | M | Irish, unknown Caucasian, possibly Cherokee, Dutch, Scottish, French, Cherokee | N/A | 0 | Hypotonia, apnea, and difficulty latching on and sucking from natural and artificial nipples | 18 |

| Tay-Sachs | F | White | c.1073+1G>A/partial deletion of HexA gene including at least exon 1 through 5′ untranslated region | N/A | N/A | 20 |

| Tay-Sachs | M | White | c.1073+1G>A/c.1073+1G>A | 3 | Sleepiness and lethargy | 12 |

| Tay-Sachs | F | Irish, unknown Caucasian, German, Swedish, English, Native American | c.986+9A>G/c.1073+1G>A | 6 | Developmental delays in crawling and walking | 16 |

| Tay-Sachs | F | White | N/A | 6 | Hypotonia | N/A |

| Tay-Sachs | M | Mexican, Italian, Scandinavian, Russian, German, Pennsylvania Dutch | c.1073+1G>A/p.L127R | 6 | Never learned to sit independently | 15 |

| Tay-Sachs | M | Dutch, English, Danish, Welsh | c.1073+1G>A/c.1073+1G>A | 4 | Episodes of staring off into space. Hypotonia | 12 |

| Sandhoff | F | Canadian | c.1614-14C>A/c.1614-14C>A | 3.5 | Cherry red spot | 3.5 |

| Sandhoff | F | French Canadian, English, Norwegian | c.115delG/c.1478T>G | 6 | Unable to sit independently | 14 |

| Sandhoff | F | White | c.901G>C/N/A | N/A | N/A | 24 |

| Sandhoff | F | Scottish, German, Northern European, Armenian | 2 partial deletions on HexB gene (at least exons 1–5 and at least exons 4–5) | 8.5 | Unable to sit independently | 12 |

| Sandhoff | F | White | Homozygous for stop codon mutation | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sandhoff | F | N/A | p.Q475X/p.S516PfsX14 | 10 | Weakness. Hypotonia. | N/A |

3.1 Age of Diagnosis

The median age of diagnosis for iGM1 was 10.5 months and for iGM2 was 15 months. Two of the patients with iGM1 were diagnosed based on the finding of a placental vacuolization in utero. The median age of onset of the first noted symptom for iGM1 was 1.5 months and for iGM2 was 6 months.

3.2 Common Clinical Changes

The most common clinical changes in the infantile gangliosidoses were onset of hypotonia within first 6 months of life, excessive oral and respiratory secretions, gastroesophageal reflux, dysphagia (followed by feeding-tube placement), and constipation (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical Change Timeline.

Clinical changes and interventions, percent of subjects experiencing them, and age of occurrence divided into 6 month age interventions

| Major clinical events | Diagnosis (N=# of subjects assessed) | Percent experiencing event | Age (months) divided into 6 month intervals at which clinical change or intervention occurred | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 | 7–12 | 13–18 | 19–24 | 25–30 | 31–36 | 37–42 | 43–48 | Experienced but age unknown | ||||

| Hypotonia | iGM1 (n=8) | 100% | 88% | 13% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=15) | 100% | 67% | 33% | |||||||||

| Eye abnormalities | strabismus | iGM1 (n=5) | 0% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 44% | 22% | 22% | |||||||||

| nystagmus | iGM1 (n=5) | 20% | 20% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 44% | 11% | 22% | 11% | ||||||||

| cherry red spot | iGM1 (n=8) | 50% | 25% | 13% | 13% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 92% | 8% | 31% | 39% | 15% | |||||||

| vision impairment first noted | iGM1 (n=6) | 17% | 17% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=10) | 60% | 20% | 20% | 10% | 10% | |||||||

| blindness | iGM1 (n=7) | 43% | 14% | 14% | 14% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 11% | 11% | ||||||||||

| Hearing Impairment | iGM1 (n=6) | 33% | 17% | 17% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 23% | 8% | 8% | 8% | ||||||||

| Dental abnormalities | gingival hyperplasia | iGM1 (n=7) | 29% | 14% | 14% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=12) | 17% | 8% | 8% | |||||||||

| anomalities of teeth formation and eruption | iGM1 (n=6) | 33% | 33% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=12) | 17% | 8% | 8% | |||||||||

| Gastrointestinal complications | feeding tube placed due to dysphagia | iGM1 (n=8) | 75% | 13% | 25% | 25% | 13% | |||||

| iGM2 (n=14) | 86% | 7% | 50% | 13% | 7% | 7% | ||||||

| hepatomegaly | iGM1 (n=8) | 50% | 38% | 13% | 13% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 46% | 8% | 8% | 23% | 8% | |||||||

| reflux | iGM1 (n=8) | 75% | 50% | 25% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=14) | 86% | 29% | 7% | 21% | 21% | 7% | ||||||

| constipation | iGM1 (n=8) | 88% | 50% | 38% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 92% | 31% | 38% | 15% | 8% | |||||||

| urinary retention | iGM1 (n=7) | 29% | 14% | 14% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=12) | 42% | 17% | 8% | 8% | 8% | |||||||

| Respiratory complications | excessive salivation or secretion | iGM1 (n=8) | 100% | 13% | 38% | 25% | 13% | |||||

| iGM2 (n=14) | 93% | 14% | 29% | 43% | 7% | |||||||

| vest chest physiotherapy initiated | iGM1 (n=8) | 75% | 13% | 25% | 38% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 77% | 8% | 46% | 15% | 8% | |||||||

| cough assistance device initiated | iGM1 (n=8) | 50% | 25% | 13% | 13% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=12) | 67% | 42% | 17% | 8% | ||||||||

| manual chest physiotherapy initiated | iGM1 (n=7) | 14% | 14% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=12) | 58% | 25% | 17% | 8% | 8% | |||||||

| Seizure onset | iGM1 (n=8) | 63% | 13% | 50% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=15) | 93% | 13% | 73% | 7% | ||||||||

| Skeletal abnormalities | vertebral beaking | iGM1 (n=4) | 50% | 25% | 25% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=11) | 0% | |||||||||||

| kyphosis | iGM1 (n=8) | 63% | 25% | 38% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 0% | |||||||||||

| scoliosis | iGM1 (n=6) | 33% | 33% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=8) | 0% | |||||||||||

| hip dislocation | iGM1 (n=8) | 50% | ||||||||||

| iGM2 (n=10) | 20% | 10% | 10% | |||||||||

| osteopenia | iGM1 (n=5) | 0% | ||||||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 0% | |||||||||||

| osteoporosis | iGM1 (n=5) | 20% | 20% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 0% | |||||||||||

| fractures | iGM1 (n=5) | 20% | 20% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=8) | 0% | |||||||||||

| Cardiac abnormalities | cardiomegaly | iGM1 (n=5) | 40% | 20% | 20% | |||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 0% | |||||||||||

| hypertension | iGM1 (n=3) | 33% | 33% | |||||||||

| iGM2 (n=9) | 0% | |||||||||||

| Sleeping problems | iGM1 (n=8) | 25% | 13% | 13% | ||||||||

| iGM2 (n=11) | 45% | 27% | 9% | 9% | ||||||||

Most patients had documented seizure disorders by 18 months of age, with the most common interval for seizure onset occurring between 13 to 18 months of age. Caregivers of patients using Syner-G reported decreases in frequency of seizures, often after optimization of anti-seizure medications had occurred. A cherry-red spot in the macula of the eye was more common in patients with iGM2 versus iGM1 (p=0.047).

3.2.1 Neurodevelopmental Changes

3.2.1.1 Motor Developmental Changes

Most patients were observed to have some form of motor developmental delay within the first 6 months of life, and all patients had documented motor developmental delay by 12 months age (Table 3). Patients with iGM1 were less likely to gain head control at any time, compared to patients with iGM2 (p=0.0096). Most patients never gained the ability to crawl. Overall, motor skills that were gained within the first 6–12 months of life were lost in most patients by the age of 2 years. There was no statistically significant difference between iGM1 and iGM2 patients when comparing the age of motor skills gained and motor skills lost. Gross motor skill scores showed rapid decline in patients receiving two or more neurodevelopmental evaluations, and had reached the floor of the testing scale by 28 months of age for all tested patients (Graph 1).

Table 3.

Motor Developmental Delay Timeline

| Motor Skills | Diagnosis (N=# of patients assessed) | Percent Never Gained | Percent Experienced | Age (months) divided into 6 month intervals at which motor developmental milestones occurred | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 | 7–12 | 13–18 | 19–24 | Experienced but age unknown | ||||

| Gained independent head control | iGM1 (n=8) | 50% | 50% | 25% | 38% | |||

| iGM2 (n=14) | 0% | 100% | 79% | 7% | 14% | |||

| Lost independent head control | iGM1 (n=8) | - | 50% | 25% | 13% | 13% | ||

| iGM2 (n=14) | - | 93% | 57% | 21% | 7% | 7% | ||

| Gained ability to sit independently | iGM1 (n=8) | 50% | 50% | 38% | 13% | |||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 62% | 39% | 31% | 8% | ||||

| Lost ability to sit independently | iGM1 (n=8) | - | 50% | 13% | 13% | 13% | 13% | |

| iGM2 (n=13) | - | 39% | 23% | 15% | ||||

| Gained ability to crawl | iGM1 (n=8) | 88% | 13% | 13% | ||||

| iGM2 (n=13) | 100% | 0% | ||||||

| Lost ability to crawl | iGM1 (n=8) | - | 13% | 13% | ||||

| iGM2 (n=14) | - | 7% | 7% | |||||

Motor developmental delays, percent of subjects experiencing them and never gained, and the age of occurrence divided into 6 month age intervals

Graph 1.

Bayley Age-Equivalent Scores for Gross Motor Domain

3.2.1.2 Cognitive Changes

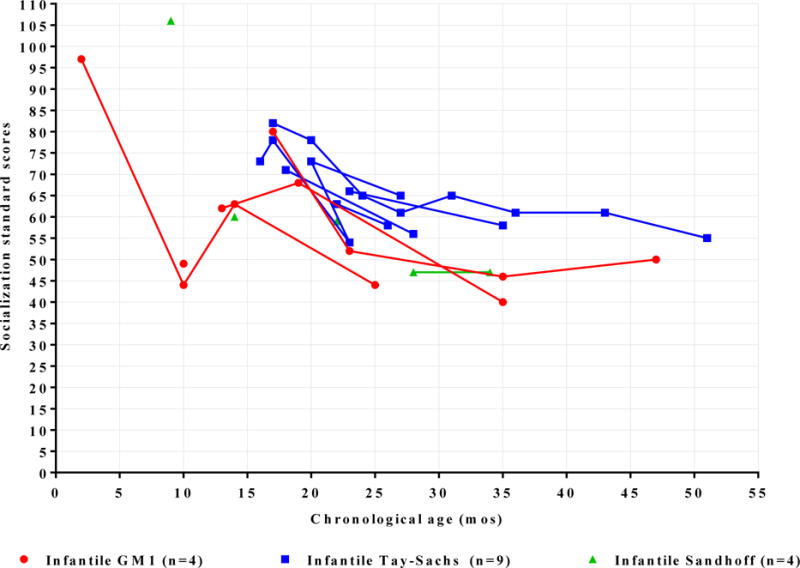

Before 18 months of age, cognitive development showed variability (Graph 2). Between 18 and 28 months of age, however, a rapid decline in cognitive development was observed. Cognitive skills became more homogenous and reached the floor of the testing scale between 18 and 28 months of age. Social skills standard scores did not exhibit the same decline as motor skills. Patients appeared to maintain measurable, albeit lower than normal, levels of social engagement between 20–28 months of age (Graph 3).

Graph 2.

Bayley -III Cognitive Development Age-Equivalent Scores

Graph 3.

Vineland - II Socialization Development Standard Scores

3.2.2 Skeletal Dysplasias

Lateral spinal X-ray evaluations were performed in 15 patients: 4 with iGM1 and 11 with iGM2. Vertebral beaking was found in 2 patients with iGM1, but was not found patients with iGM2. Kyphosis was more common in iGM1 than in iGM2 patients (p=0.0028).

3.2.3 Cardiology Findings

Cardiology evaluations were done in 5 patients with iGM1 and 9 patients with iGM2. Of these patients, cardiomegaly was found in 2 of the 5 patients with iGM1, but was not found in the iGM2 patients. Other than cardiomegaly, cardiology findings were unremarkable.

3.3 Survival

3.3.1 Survival Overview

The median survival for all patients with iGM1 was 45.91 months (range for ages of death: 10.32–56.90 months); and 43.43 months for all patients with iGM2 (range for ages at death: 33.08–66.83 months) (p=0.67). Two patients with iGM1 did not have feeding-tubes. Of these patients, one died at the age of 16.79 months, and one is still alive at 15.05 months. Excluding the two patients with iGM1 who did not have a feeding-tube, the median survival for iGM1 was 45.91 months. All patients with iGM2 had a feeding-tube. Of patients with iGM2, median survival of patients with iTS was 48.32 months (range for ages at death: 35.09–66.83 months), and for patients with iSD was 41.32 months (range for ages at death: 33.08–41.56 months) (p=0.34). The most common reported cause of death was respiratory failure associated with aspiration pneumonia, for both iGM1 and iGM2 patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Causes of Death in Infantile Gangliosidoses

| Cause of death | Infantile GM1 (n=6) | Infantile Tay-Sachs (n=6) | Infantile Sandhoff (n=3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure | 100% | 67% | 67% |

| Unknown | 0% | 33% | 33% |

Of patients not receiving treatment with Syner-G, who also had feeding-tubes (3 with iGM1 and 8 with iGM2), patients with iGM2 showed a trend toward a longer survival compared to patients with iGM1 (p=0.051) (Graph 4).

Graph 4.

Survival of Infantile GM1 and Infantile GM2 Subjects Not on Syner-G

*ALL patients represented have feeding tubes.

3.3.2 Survival Using Syner-G Therapy

All patients who received Syner-G (miglustat medication combined with ketogenic diet) also had a feeding-tube placed. Three patients with iGM1 (out of 6 patients total with iGM1 who had feeding-tubes), 3 of 9 patients with iTS, and 2 of 6 patients with iSD, received treatment with Syner-G. The patients that consented to the Syner-G study also consented to the natural history study. The median survival for patients with iGM1 receiving Syner-G was 55.70 months (range for ages at death: 54.51–56.90 months), compared to 19.09 months for those not receiving Syner-G (range for ages at death: 10.32–37.32 months) (p=0.025) (Graph 5). Median survival for patients with iGM2 (iTS and iSD) receiving Syner-G was 49.97 months (range of ages at death: 41.56–66.83 months), compared to 41.06 months for those not receiving Syner-G (range of ages of death: 33.08–48.33 months) (p=0.19) (Graph 6).

Graph 5.

Survival of Infantile GM1 Subjects: Syner-G versus No Syner-G

*ALL patients represented have feeding tubes.

Graph 6.

Survival of Infantile GM2 Subjects: Syner-G versus No Syner-G

*ALL patients represented have feeding tubes.

3.3.3 Survival Using Chest Physiotherapy

Among palliative therapies, chest physiotherapy (either hand-percussion and/or high frequency chest wall oscillating device (HFCWO)) was associated with a statistically significant prolonged survival in patients with iGM1 (p=0.0056). Statistical analysis of chest physiotherapy and survival in the iGM2 patients was not possible because only one out of 15 patients with iGM2 was not using chest physiotherapy. Per parent report, patients with iGM1 and iGM2 experienced fewer respiratory infections and hospitalizations after initiating chest physiotherapy.

4.0 Discussion

This is the first study to prospectively evaluate the natural history of infantile gangliosidoses during regular clinical care, for both the iGM1 and iGM2 diseases [7]. It is also the first study to develop a timeline to characterize clinical changes and clinical interventions that commonly occur in infantile gangliosidoses. Such a timeline may serve as a tool to guide parents and clinicians in clinical planning, and this tool may be further detailed as additional information about the natural history and associated treatments become available.

When comparing iGM1 to iGM2, there were numerous similarities, as illustrated by the clinical timelines. Hypotonia and developmental delays were usually noted by 6 months of age in both iGM1 and iGM2. Consistent with this, a natural history survey of 92 patients with iGM2 conducted by Bley, et al found similar timing of symptom onset [3]. A review article by Regier, et al reported symptom onset in iGM1 to be 3 to 6 months of age.[5] The timeline from our prospective natural history study shows that onset of seizures is most common between 7 and 18 months of age for both iGM1 and iGM2. There were no significant differences between iGM1 and iGM2 in the age of motor skills gained and motor skills lost. Cognitive skills became more homogenous and reached the floor of the testing scale when all patients were 18 to 28 months of age. It should be noted that all patients receiving neurodevelopmental testing were also receiving medications that can cause fatigue and lethargy (e.g., anti-seizure medications, muscle relaxants). The sedating medications, as well as the generalized profound hypotonia, may interfere with accurate and consistent cognitive and motor skill testing scores.

4.1 Clinical Outcome Measure Candidates

Identifying meaningful clinical outcomes for patients with infantile gangliosidoses is based in a setting of a rapidly progressive and fatal disease course. Importantly, this study showed that most patients have severe neurological impairment long before diagnosis is made. The concern that neurological impairment present at time of diagnosis may be irreversible, acts as a deterrent to aggressive efforts to develop therapies. Clearly, earlier treatment would be desirable in this population.

The timeline of clinical changes shows commonalities that may be candidates for clinical outcomes measures for future clinical trials. Homogeneity of clinical changes included prevalence and, importantly, timing of onset for hypotonia, seizures, nadir in neurodevelopmental parameters, and death. All patients suffered excessive salivary and respiratory secretions and recurrent respiratory infections.

4.2 Feeding-Tube Placement

Development of dysphagia is inevitable in the infantile gangliosidoses, as reported in other studies and as reflected in the clinical timeline of changes shown in this study [3–5]. Dysphagia, in turn, increases risk of aspiration pneumonia, which is the most common cause of death in infantile gangliosidoses. During the course of this study, it became apparent to the investigators that earlier feeding-tube placement may be advantageous instead of waiting until aspiration and malnutrition complications became more pronounced. Feeding-tube placement was therefore encouraged by the investigators, despite patients’ parents often having the perception that feeding-tube placement was a last-resort effort to save an already failing child. Bley, et al found that median survival in iGM2 has actually increased during the past 50 years, and this is attributed largely to feeding-tube placement [3].

4.3 Other Factors Associated with Survival

During this study, respiratory complications, most often aspiration pneumonia, were the most common cause of death, regardless of which treatments or palliative therapies the patients were using. It became apparent, however, during the study that the frequency of respiratory illnesses could be mitigated by chest physiotherapy (either hand-percussion and/or HFCWO). Chest physiotherapy was associated with a prolonged survival in iGM1, which was statistically significant (p=0.0056). Parents reported fewer respiratory infections and hospitalizations after initiation of chest physiotherapy, although these parent reports were not confirmed with the patients’ local hospital and clinical records at the time of this analysis. HFCWO allows for administration of chest physiotherapy with a consistent technique, whereas hand-percussion physiotherapy is more dependent on the individual techniques and abilities of the caregiver. Although chest physiotherapy is most often associated with cystic fibrosis disease management, it is becoming increasingly common for children with severe neurological impairment to receive both HFCWO and hand-percussion therapy [22]. It was found that the patients in this study had often been prescribed hand-percussion therapy before enrollment. During this study, the investigators encouraged use of HFCWO for all patients, as well as hand-percussion therapy.

4.4 Syner-G

The investigators regularly offered the Syner-G therapy, a synergistic administration of substrate-reducing therapy using miglustat paired with a ketogenic diet, and evaluated its impact on those patients who were adherent in comparison to those who did not adopt the therapy. All patients on Syner-G also had a feeding-tube placed. There was an increase in median survival in patients with iGM1 who received Syner-G compared to those not using Syner-G (p=0.025). Patients with iGM2 receiving Syner-G showed a trend toward increased survival (p=0.19). Although all patients using Syner-G also had feeding-tubes placed, the timing of feeding-tube placement varied. Due to the small study population and variations in palliative care measures (e.g., timing of feeding-tube placement, chest physiotherapy), the impact of Syner-G on survival is not yet fully understood.

4.4.1 Syner-G Therapy Background

Miglustat is a small molecule that has partial bioavailability in the CNS after oral administration and reduces production of a number of glycosphingolipids, including GM1 and GM2 gangliosides. Miglustat works through inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase in the glycosphingolipid pathway [23]. For this reason, miglustat was thought to hold potential usefulness towards decreasing pathological accumulation of GM1 and GM2 gangliosides in the gangliosidosis diseases [12–14,24].

The most common adverse effects of miglustat are gastrointestinal and include diarrhea, flatulence, and abdominal pain [15,21,24]. The gastrointestinal side effects are due to miglustat’s inhibition of the disaccharidase digestive enzymes in the gut, primarily maltase, sucrase, and to a lesser degree, lactase [15,21,24]. The disaccharidase inhibition can cause side effects of osmotic diarrhea when patients eat starchy foods and foods containing a high amount of carbohydrate [15]. Therefore, patients using miglustat must abide by a low-carbohydrate diet if risk of gastrointestinal side effects is to be minimized.

In this study, the ketogenic diet made it possible for the patients using Syner-G to tolerate miglustat therapy well, while simultaneously maintaining adequate nutrition. Of note, the ketogenic diet has demonstrated safety and efficacy for seizure management in infants and young children for many decades, and this has included notable results in children with seizures of a metabolic disease origin [25–29]. Moreover, seizures have been recognized as one of the most common day-to-day complications of infantile gangliosidoses, and use of the ketogenic diet in this population is not uncommon [3,5,28,29]. Thus, Syner-G combined miglustat with ketogenic diet to allow for higher doses of miglustat while mitigating gastrointestinal side effects, and simultaneously, working to improve seizure management.

4.5 Newborn screening

If newborn screening were to become available for the gangliosidoses, treatment before onset of visible symptoms would be possible and this might dramatically change treatment approaches and treatment outcome expectations. Interestingly, two of the patients with iGM1 were diagnosed based on the histological findings of vacuolization of cells in the placenta. These findings were incidental, resulting from the delivering physician’s observation of an abnormal-appearing placenta.

4.6 Future Considerations

This study identifies a pattern of occurrence of important clinical events in a small group of patients with infantile gangliosidoses. The rarity of the gangliosidosis diseases, the very short lifespan, and the severity of the diseases makes study of larger populations challenging. Despite the small population size, the prospective nature of this study was valuable, as most of the information in the available scientific literature has been gathered retrospectively. Future studies of the timeline of clinical events in these patients may start with the model created in this study and work to reinforce this model and make it more informative, as additional information becomes available.

It is important to recognize that the infantile gangliosidosis phenotype is distinguished from the juvenile and late-onset phenotypes, not only by its earlier presentation, more rapid progression and early lethality, but also by its homogeneity [3,5,8]. The consistent pattern of death between the age of 3 and 4 years in the infantile phenotype suggests overall survival (OS) may be a meaningful outcome measure for treatment studies. OS is not commonly used as an outcome measure in clinical trials of lysosomal diseases. It was, however, used in the pivotal enzyme replacement therapy trials for infantile Pompe disease, which has a marked homogeneous phenotype [30]. OS is used frequently as an outcome measure in clinical trials for a number of other conditions that have a rapid disease course and end in death, notably advanced stages of cancer. In fact, in oncology clinical trials, OS is considered the “gold standard” as an outcome measure for diseases in which the expected survival after enrollment is 5 years or less [31].

The investigators for this natural history study propose that patients with the infantile gangliosidosis phenotype should be considered for early-stage clinical trials, and this group may in fact be the preferred population for new investigational agents for gangliosidoses, with OS as a primary outcome.

5.0 Conclusions/Summary

This natural history study has brought to light the following strategic considerations for clinical trial design:

Diagnosis of infantile gangliosidoses most often occurs in the second year of life, after severe, system-wide neurological damage is well established. The disease progresses rapidly and aggressively, with life ending between 3 and 4 years of age. This delay in diagnosis precludes prevention of many neurologic pathologies and the slowing or reversal of disease symptoms as clinical outcome measures for treatment trials.

The extremely short lifespan and reliability of timing of death suggest that overall survival is the primary outcome measure of choice for initial clinical trial design in the infantile gangliosidoses.

The homogeneity of the infantile gangliosidoses phenotype as demonstrated by the clinical timeline in this study may provide promising secondary outcome measure candidates.

Syner-G may have prolonged lifespan in this study, but the population size and other palliative care measures used prevent conclusions at this time.

Combination therapy approaches that include treatments that address the underlying disease pathology, as well as palliative therapies, may produce better clinical outcomes in comparison to monotherapy approaches. Chest physiotherapy was associated with prolonged survival and decreased frequency of respiratory infection, and therefore should be considered for patients with gangliosidoses.

In the absence of newborn screening programs, early diagnosis before onset of visible symptoms will not occur. Histopathologic evaluation of placenta at time of birth, with attention to inclusion pathology, may aid in early diagnosis of some children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the Lysosomal Disease Network (U54NS065768). The Lysosomal Disease Network (U54NS065768) is a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), supported through collaboration between the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR) at the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest pertaining to the research reported in this manuscript.

7.0 References

- 1.Sarafoglou K, Hoffmann GF, Roth KS. Pediatric Endocrinology and Inborn Errors of Metabolism. New York: McGraw-Hill Company; 2009. pp. 738–739.pp. 744–745. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barranger JA, Cabrera-Salazar MA. Lysosomal Storage Disorders. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bley AE, Giannikopoulos OA, Hayden D, Kubilus K, Tifft CJ, Eichler FS. Natural history of infantile G(M2) gangliosidosis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1233–1241. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith NJ, Winstone AM, Stellitano L, Cox TM, Verity CM. GM2 gangliosidosis in a UK study of children with progressive neurodegeneration: 73 cases reviewed. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(2):176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regier DS, Proia RL, D’Azzo A, Tifft CJ. The GM1 and GM2 gangliosidoses: natural history and progress toward therapy. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2016;13(Suppl 1):663–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannebley JS, Silveira-Moriyama L, Bastos LO, Steiner CE. Clinical findings and natural history in ten unrelated families with juvenile and adult GM1 gangliosidosis. JIMD Rep. 2015;24:115–122. doi: 10.1007/8904_2015_451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maegawa GH, Stockley T, Tropak M, Banwell B, Blaser S, Kok F, Giugliani R, Mahuran D, Clarke JT. The natural history of juvenile or subacute GM2 gangliosidosis: 21 new cases and literature review of 134 previously reported. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1550–1562. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neudorfer O, Kolodny EH. Late-onset Tay-Sachs disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6(2):107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frey LC, Ringel SP, Filley CM. The natural history of cognitive dysfunction in late-onset GM2 gangliosidosis. Arch Neurol. 2005 Jun;62:6, 989–994. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarpelli M, Tomelleri G, Bertolasi L, Salviati A. Natural history of motor neuron disease in adult onset GM2-gangliosidosis: a case report with 25 years of follow-up. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2014 Jul 2;1:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.06.002. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condori J, Acosta W, Ayala J, Katta V, Flory A, Martin R, Radin J, Cramer CL, Radin DN. Enzyme replacement for GM1 gangliosidosis: uptake, lysosomal activation, and cellular disease correction using a novel β-galactosidase:RTB lectin fusion. Mol Genet Metab. 2016 Feb;117:2, 199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.12.002. Epub 2015 Dec 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bembi B, Marchetti F, Guerci VI, Ciana G, Addobbati R, Grasso D, Barone R, Cariati R, Fernandez-Guillen L, Butters T, Pittis MG. Substrate reduction therapy in the infantile form of Tay-Sachs disease. Neurology. 2006;66(2):278–280. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194225.78917.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maegawa GH, van Giersbergen PL, Yang S, Banwell B, Morgan CP, Dingemanse J, Tifft CJ, Clarke JT. Pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of miglustat in the treatment of pediatric patients with GM2 gangliosidosis. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97(4):284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro BE, Pastores GM, Gianutsos J, Luzy C, Kolodny EH. Miglustat in late-onset Tay-Sachs disease: a 12-month, randomized, controlled clinical study with 24 months of extended treatment. Genet Med. 2009;11(6):425–433. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a1b5c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belmatoug N, Burlina A, Giraldo P, Hendriksz CJ, Kuter DJ, Mengel E, Pastores GM. Gastrointestinal disturbances and their management in miglustat-treated patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(5):991–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treiber A, Morand O, Clozel M. The pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of the glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor miglustat in the rat. Xenobiotica. 2007;37(3):298–314. doi: 10.1080/00498250601094543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denny CA, Heinecke KA, Kim YP, Baek RC, Loh KS, Butters TD, Bronson RT, Platt FM, Seyfried TM. Restricted ketogenic diet enhances the therapeutic action of N-butyldeoxynojirimycin towards brain GM2 accumulation in adult Sandhoff disease mice. J Neurochem. 2010;113(6):1525–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roach KE. Measurement of health outcomes: reliability, validity and responsiveness. American Academy of Orthotists and Prosthetists. 2006;18:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development®. (Third) (Bayley-III®). http://www.pearsonclinical.com/childhood/products/100000123/bayley-scales-of-infant-and-toddler-development-third-edition-bayley-iii.html, 2017, accessed 2-14-2017.

- 20.Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. (Second) doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/10.2.215. (Vineland™-II). http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000668/vineland-adaptive-behavior-scales-second-edition-vineland-ii-vineland-ii.html, 2017, accessed 2-14-2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Zavesca (miglustat) full prescribing information. Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc; 2016. https://www.zavesca.com/pdf/ZAVESCA-Full-Prescribing-Information.pdf, accessed 2-15-2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauer JM. Caring for children who have severe neurological impairment: a life with grace. John Hopkins Press Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summary of product characteristics: Zavesca. Actelion Manufacturing GmbH, Grenzach-Wyhlen; Germany: 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000435/WC500046726.pdf, accessed 2-15-2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coutinho MF, Santos JI, Alves S. Less is more: substrate reduction therapy for lysosomal storage disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(7) doi: 10.3390/ijms17071065. pii: E1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zupec-Kania BA, Spellman E. An overview of the ketogenic diet for pediatric epilepsy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23(6):589–596. doi: 10.1177/0884533608326138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zupec-Kania BA, Aldaz V, Montgomery ME, Kostas KC. Enteral and parenteral applications of ketogenic diet therapy. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition. 2011;3(5):274–281. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kossoff EH, Zupec-Kania BA, Amark PE, Ballaban-Gil KR, Christina Bergqvist AG, Blackford R, Buchhalter JR, Caraballo RH, Helen Cross J, Dahlin MG, Donner EJ, Klepper J, Jehle RS, Kim HD, Christiana Liu YM, Nation J, Nordli DR, Jr, Pfeifer HH, Rho JM, Stafstrom CE, Thiele EA, Turner Z, Wirrell EC, Wheless JW, Veggiotti P, Vining EP, Charlie Foundation, Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. International Ketogenic Diet Study Group Optimal clinical management of children receiving the ketogenic diet: recommendations of the International Ketogenic Diet Study Group. Epilepsia. 2009;50(2):304–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeyakumar M, Butters TD, Dwek RA, Platt FM. Glycosphingolipid lysosomal storage diseases: therapy and pathogenesis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2002;28(5):343–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2002.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nalini A, Christopher R. Cerebral glycolipidoses: clinical characteristics of 41 pediatric patients. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(6):447–452. doi: 10.1177/088307380401900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klinge L, Straub V, Neudorf U, Schaper J, Bosbach T, Görlinger K, Wallot M, Richards S, Voit T. Safety and efficacy of recombinant acid alpha-glucosidase (rhGAA) in patients with classical infantile Pompe disease: results of a phase II clinical trial. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005 Jan;15:1, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKee AE, Farrell AT, Pazdur R, Woodcock J. The role of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration review process: clinical trial endpoints in oncology. Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 1):13–18. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]