Abstract

This communication describes a method for the Ni(cod) 2-mediated intramolecular arylation of alkyl C–H bonds adjacent to the nitrogen atom in benzamide substrates. The transformation proceeds at room temperature and exhibits selectivity for functionalization of more substituted C–H bonds. The yields of the desired isoindolinone products are higher with benzamide substrates containing tertiary alkyl groups on the nitrogen atom than with those bearing primary or secondary alkyls. The results described herein suggest a mechanism involving radical intermediates for these reactions.

Keywords: amides, arylation, intramolecular, nickel, halides

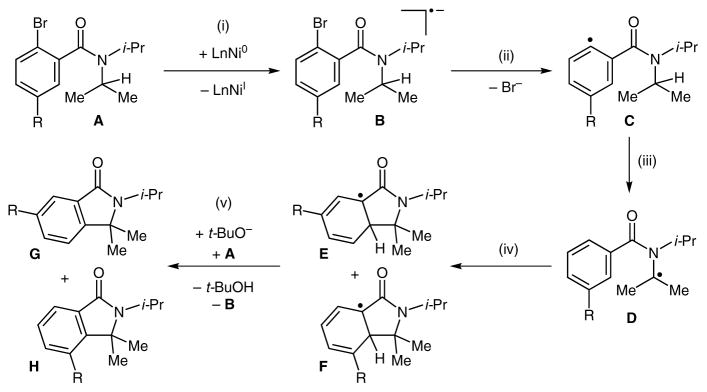

Palladium-catalyzed direct arylation of both sp2 and sp3 C–H bonds has emerged as a powerful strategy for the construction of C–C bonds.1,2 Recently, however, there has been an increasing demand to replace precious-metal catalysts with earth-abundant metals.3 The development of nickel-catalyzed C–H arylations, analogous to known Pd-catalyzed transformations, has the potential to significantly enhance the economic viability and synthetic applicability of C–H arylation protocols. In light of this advantage, a number of research groups have described the nickel-catalyzed arylation of C(sp2) -H bonds.3,4 In contrast, examples of nickel-catalyzed arylation of alkyl C–H bonds are rare: Liu et al. achieved the nickel-catalyzed oxidative arylation of alkyl C–H bonds by using arylboronic acids (Scheme 1, a) 5 and the groups of Chatani and You have reported the intermolecular ligand-directed arylation of sp3 C–H bonds using aryl halides (halide = I, Br) (Scheme 1, b) .6

Scheme 1.

Previous reports of nickel-catalyzed sp3 C–H bond arylation

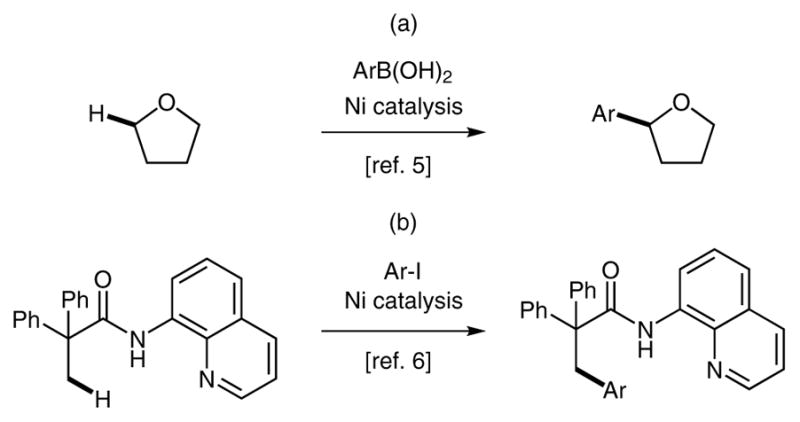

Recently, we published an example of nickel-mediated synthesis of isoindolinones through intramolecular coupling of an aryl halide with a C(sp3) –H bond (Scheme 2, a) .7,8 Despite the efficiency of these arylations mediated by bis(1,5-cyclooctadiene) nickel(0) [Ni(cod) 2], their synthetic applicability is limited by the requirement for high temperatures (145°C) . Since our initial report, we have made efforts to address this drawback and have identified conditions that allow the analogous nickel-mediated synthesis of isoindolinones to take place at room temperature. Herein, we detail the scope and limitations of these transformations (Scheme 2, b) . To our knowledge, these reactions represent the first example of nickel-mediated arylation of sp3 C–H bonds using aryl halides at ambient temperatures.

Scheme 2.

Our previous results and proposed work

Our investigations toward establishing more moderate conditions for nickel-mediated isoindolinone synthesis began with a detailed screen of solvents, bases, and nickel sources for the reaction of benzamide 1-Br at room temperature (Table 1) . As shown in Table 1, the use of Ni(cod) 2 in conjunction with sodium tert-butoxide afforded 1a in a number of solvents at room temperature, albeit in low yields (entries 1–5) . Interestingly, however, simple replacement of sodium tert-butoxide with potassium tert-butoxide enabled excellent yields of 1a to be obtained after the same period of time (entry 6) . Similar cation effects have been observed for C(aryl) –H coupling with aryl halides.9 Dioxane and tetrahydrofuran performed equally well as solvents for the arylation using potassium tert-butoxide as the base (entries 6 and 7) . Importantly, no reaction was observed in the absence of a nickel source. However, a number of nickel(II) salts also induced formation of 1a, albeit in low yields (entries 9–12) . The addition of triphenylphosphine as a potential reductant for nickel(II) did not significantly affect the observed yield of 1a under these conditions (cf. entries 9, 12 with 13 and 14) . As such, conditions employing Ni(cod) 2 in conjunction with potassium tert-butoxide in tetrahydrofuran were identified as optimal for the formation of the desired iso-indolinone.

Table 1.

Optimization of Room-Temperature Arylationsa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Entry | [Ni] | Base | Solvent | Yield of 1a (%) b |

| 1 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuONa | dioxane | 20 |

| 2 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuONa | THF | 5 |

| 3 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuONa | xylene | 8 |

| 4 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuONa | DMF | 27 |

| 5 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuONa | NMP | 33 |

| 6 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuOK | dioxane | 99c |

| 7 | Ni(cod) 2 | t-BuOK | THF | 100 |

| 8 | none | t-BuOK | THF | 0 |

| 9 | Ni(OAc) 2 | t-BuOK | THF | 24 |

| 10 | NiCl2(PCy3) 2 | t-BuOK | THF | 22 |

| 11 | Ni(acac) 2 | t-BuOK | THF | 25 |

| 12 | NiBr2·DMEd | t-BuOK | THF | 24 |

| 13e | Ni(OAc) 2 | t-BuOK | THF | 27c |

| 14e | NiBr2·DMEd | t-BuOK | THF | 29c |

Reaction conditions: Ni(cod) 2 (0.1 equiv) , base (1.5 equiv) , solvent, r.t., 21 h.

1H NMR yields against 1,4-dinitrobenzene as the internal standard unless otherwise noted.

Calibrated GC yields against hexadecane as the internal standard.

DME = 1,2-Dimethoxyethane

General conditions, but with Ph3P (0.2 equiv) .

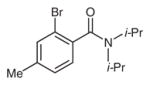

We next investigated the generality of this reaction with respect to electronically varied benzamide substrates. As shown in Table 2, the chloride (1-Cl) and iodide (1-I) analogues of 1-Br could also be used to form 1a in excellent yields (entry 1) . Additionally, aryl rings bearing electron-donating (entry 2) or electron-withdrawing substituents (entry 4) underwent the desired transformation to provide isoindolinone products in modest to excellent yields. The moderate yield of product 4a is partly attributed to a competing SNAr reaction to yield products (detected by GC/MS analysis of the crude reaction mixtures) in which F is substituted by the tert-butoxide anion.

Table 2.

Scope of Intramolecular Arylations

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yielda,b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1-Br X = Br 1-Cl X = Cl 1-I X = I |

1a |

X = Br, 96% X = Cl, 94% X = I, 96% |

| 2 |

2-Br X = Br 2-Cl X = Cl |

2a |

X = Br, 92% X = Cl, 83% |

| 3 |

3-Br |

3a |

99% |

| 4 |

4-Br X = Br 4-Cl X = Cl |

4a |

X = Br, 51% X = Cl, 74% |

| 5 |

5-Br |

5a |

96% |

Reaction conditions: Ni(cod) 2 (0.1 equiv) , t-BuOK (1.5 equiv) , THF, r.t.

Isolated yield.

Table 3 depicts the site-selectivities observed for the intra-molecular arylation reaction using substrates that can lead to isomeric products. The site-selectivity for the reaction of 6-Br, 6-I, and 7-Br exemplifies the preference for arylation of more substituted sp3 C–H bonds. The reaction is more efficient with substrates containing tertiary alkyls on the N atom than those bearing primary or secondary alkyls (entries 1–3 versus 4–7) . Interestingly, this selectivity is orthogonal to that documented for palladium-catalyzed arylations.10 For example, whereas the nickel-mediated reaction of 6-Br affords 6a as the major product, isomer 6b is the observed product under palladium catalysis. Furthermore, benzamides containing two different tertiary N-alkyl groups (8-Br and 9-Br) afforded an approximately 1:1 mixture of isomeric isoindolinones (entries 4 and 5) . Finally, use of meta-substituted amide substrates 10-Cl and 11-Br led to a ca. 1:1.5 mixture of isomeric products (entries 6 and 7) .

Table 3.

Site-Selectivity of Intramolecular Arylation Reactionsa

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield (%) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1d |

6-Br |

6a |

6b |

45 (1:0) c |

| 2d |

6-I |

6a |

6b |

52 (1:0) c |

| 3d |

7-Br |

7a |

7b |

60e (4:1) f |

| 4 |

8-Br |

8a |

8b |

84 (1.1:1) c |

| 5 |

9-Br |

9a |

9b |

91 (1.2:1) c |

| 6 |

10-Cl |

10a |

10b |

92 (1:1.6) c |

| 7d |

11-Br |

11a |

11b |

53 (1:1.5) c |

Reaction conditions: Ni(cod) 2 (0.1 equiv) , t-BuOK (1.5 equiv) , THF, r.t.

Isolated yield.

Selectivity determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

General conditions but with Ni(cod) 2 (0.2 equiv) .

Reported yield of the major isomer only.

Selectivity determined by GC/MS analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

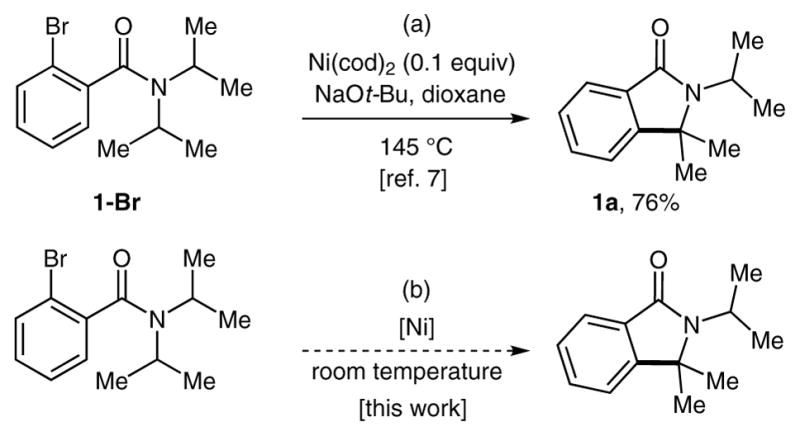

The yield and site-selectivities of the room-temperature arylation shown in Tables 2 and 3 are comparable to those that we previously reported using the Ni(cod) 2/sodium tert-butoxide conditions at 145°C.7 A plausible mechanism consistent with the observed reactivity and selectivity of this system is depicted in Scheme 3. It involves: (i) single electron transfer from a Ni(0) complex to the substrate A to generate the radical anion B,11 (ii) loss of Br− to afford aryl radical C, (iii) intramolecular H-atom abstraction to give D, (iv) radical addition to the arene to afford isomeric intermediates E and F, and, finally (v) rearomatization to release the product and regenerate B. Importantly, this mechanism is similar to those proposed for potassium tert-butoxide mediated coupling of aromatic C–H bonds with aryl halides.12–15

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism

The pathway depicted in Scheme 3 is consistent with a number of observations. First, the diminished yield of the desired products in the presence of a radical scavenger (Scheme 4) implicates the possible involvement of radical intermediates. Second, the preferential functionalization of more substituted tertiary C–H bonds is in agreement with the proposed intermediacy of alkyl radical species such as D (Scheme 3) . Finally, the negligible site-selectivity observed with meta-substituted benzamide substrates is consistent with a fast, unselective radical reaction as depicted in step (iv) .

Scheme 4.

Effect of radical scavengers

This communication describes a method for the nickel-mediated room-temperature intramolecular arylation of sp3 C–H bonds adjacent to amide nitrogen atoms by using aryl halides (halide = Cl, Br, I) . These arylation reactions afford electronically and sterically diverse isoindolinone products in good to excellent yields. In general, the yields of the desired arylated products are higher with substrates bearing electron-rich and electron-neutral aryl rings, and the reactions display selectivity for the functionalization of tertiary over primary and secondary alkyl C–H bonds.

The comparable selectivities of these room-temperature arylations to those obtained in the previously reported Ni(cod) 2/sodium tert-butoxide system at 145°C suggest similar mechanistic pathways for the two transformations.

NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker 400 (399.96 MHz for 1H; 100.57 MHz for 13C) spectrometer. 1H NMR chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to TMS, with the residual solvent peak used as internal reference. Multiplicities are reported as: singlet (s) , doublet (d) , doublet of doublets (dd) , triplet of doublets (td) , triplet (t) , multiplet (m) , or septet (sept) . IR spectra were obtained with a Thermo scientific Nicolet iS5 iD5 ATR spectrophotometer. Melting points were obtained with a Thomas Hoover melting point apparatus.

Anhydrous t-BuONa, t-BuOK, 2-chlorobenzoyl chloride, anhydrous diisopropylamine, dicyclohexylamine, diisopropylethyl amine, N-ethyl-N-isopropyl amine, galvinoxyl free radical, thionyl chloride (SOCl2) , and anhydrous Et3N were obtained from Aldrich and used as received. Ni(cod) 2 was obtained from Strem chemicals and used as received. 2-Bromo-4-fluorobenzoyl chloride and 2-bro-mo-5-trifluoromethylbenzoic acid were obtained from Matrix Scientific and used as received. 2-Bromobenzoyl chloride was obtained from TCI America and used as received. Substrates 1-Br,7 1-Cl,7 1-I,14 2-Br,7 2-Cl,7 3-Br,7 4-Br,7 4-Cl,7 5-Br,7 6-Br,7 6-I,16 and 10-Cl,7 were prepared by following reported procedures. Anhydrous xylene and anhydrous dioxane was obtained from Aldrich and used as received. Anhydrous CH2Cl2, anhydrous THF, and anhydrous Et2O were purified by using a Glass Contour solvent purification system column composed of neutral alumina. Toluene was purified by using a Glass Contour solvent purification system column composed of neutral alumina and a copper catalyst. DMF was purified with a Glass Contour solvent purification system by passing through a column packed with molecular sieves. Other solvents were obtained from Fisher Chemical or VWR Chemical and used without further purification. Flash chromatography was performed on EM Science silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063mm particle size, 230–400 mesh) and thin-layer chromatography was performed with An-altech TLC plates pre-coated with silica gel 60 F254.

2-Bromo-N-ethyl-N-isopropylbenzamide (7-Br)

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask containing a solution of N-ethyl-N-iso-propylamine (0.597 g, 6.85 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , in anhydrous Et2O (22 mL) was added diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA; 0.89 g, 6.85 mmol, 1.50 equiv) under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C using an ice bath and 2-bromobenzoyl chloride (1.00 g, 4.56 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added dropwise. The resulting mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, then transferred to a separatory funnel using EtOAc (20 mL) and washed with sat. aq NaCl (3×30 mL) . The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, concentrated, and purified by chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 70:30) to afford product 7-Br.

Yield: 595 mg (48% yield) ; white solid; mp 96–97°C; Rf = 0.40 (hexanes–EtOAc, 70:30) .

IR (neat film) : 2972, 1622, 1587, 1444, 1420, 1341, 1316, 1216, 1103, 1023, 775, 753, 615cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ (mixture of rotamers) = 7.55 (t, J = 7.0Hz, 1H) , 7.35–7.31 (m, 1H) , 7.27–7.19 (m, 2H) , 4.77 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 0.3H) , 3.69–3.53 (m, 1.4H) , 3.35–3.27 (m, 0.7H) , 3.18–3.02 (m, 0.6H) , 1.32 (t, J = 7.1Hz, 2H) , 1.30 (d, J = 6.9Hz, 2H) , 1.24 (d, J = 6.7Hz, 2H) , 1.06 (d, J = 6.7Hz, 2H) , 1.00 (t, J = 7.2Hz, 1H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ (mixture of rotamers) = 168.9, 168.2, 139.3, 139.2, 132.8, 132.7, 129.7, 127.7, 127.5, 127.4, 119.1, 50.3, 46.0, 39.0, 35.3, 21.2, 21.1, 20.6, 20.1, 16.2, 14.4.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C12H16BrNO: 292.0307; found: 292.0302.

2-Bromo-N-cyclohexyl-N-isopropylbenzamide (8-Br)

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask containing a solution of N-cyclohexyl-N-isopropylamine (0.97 g, 6.85 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , in anhydrous Et2O (22 mL) was added DIPEA (0.885 g, 6.85 mmol, 1.50 equiv) under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C using an ice bath and 2-bromobenzoyl chloride (1.00 g, 4.56 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added dropwise. The resulting mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, then transferred to a separatory funnel using EtOAc (20 mL) and washed with sat. aq NaCl solution (3×30 mL) . The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, concentrated, and purified by chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) to afford 8-Br.

Yield: 1.44 g (97%) ; white solid; mp 74–76°C; Rf = 0.34 (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) .

IR (neat) : 2924, 1624, 1589, 1451, 1436, 1370, 1346, 1325, 992, 764, 749, 737, 693, 647cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ (mixture of rotamers) = 7.55 (d, J = 8.0Hz, 1H) , 7.33–7.29 (m, 1H) , 7.21–7.14 (m, 2H) , 3.65–3.50 (m, 1H) , 3.11–2.99 (m, 1H) , 2.76–2.62 (m, 1H) , 2.01–0.90 (m, 15H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ (mixture of rotamers) = 168.4, 168.2, 140.3, 140.1, 132.82, 132.76, 129.4, 129.3, 127.5, 127.4, 126.50, 126.46, 118.9, 60.0, 54.9, 51.2, 47.2, 31.2, 31.0, 29.9, 29.4, 26.7, 26.5, 25.7, 25.6, 25.3, 25.1, 20.8, 20.6, 20.1.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H22BrNO: 346.0777; found: 346.0787.

2-Bromo-N-cyclohexyl-4-fluoro-N-isopropylbenzamide (9-Br)

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask containing a solution of N-cyclohexyl-N-isopropylamine (0.44 g, 3.12 mmol, 1.49 equiv) , in anhydrous Et2O (11 mL) was added DIPEA (0.41 g, 3.17 mmol, 1.51 equiv) under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C using an ice bath and 2-bromo-4-fluorobenzoyl chloride (0.5 g, 2.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added dropwise. The resulting mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, then transferred to a separatory funnel using EtOAc (20 mL) and extracted with sat. aq NaCl solution (3×30 mL) . The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, concentrated, and purified by chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) to afford product 9-Br.

Yield: 562 mg (78%) ; light-yellow solid; mp 90–91°C; Rf = 0.43 (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) IR (neat) : 2915, 1622, 1595, 1441, 1371, 1355, 1345, 1326, 1260, 1193, 1127, 892, 879, 869, 815, 584cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.30 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.3Hz, 0.5H) , 7.29 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.3Hz, 0.5H) , 7.143 (dd, J = 8.8, 5.8Hz, 0.5H) , 7.136 (dd, J = 8.5, 5.5Hz, 0.5H) , 7.03 (td, J = 8.3, 2.5Hz, 1H) , 3.62–3.49 (m, 1H) , 3.08–2.97 (m, 1H) , 2.70–2.59 (m, 1H) , 1.98–0.91 (m, 15H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 167.6, 167.5, 161.7 (JC–F = 250Hz) , 136.6, 136.5, 127.6 (JC–F = 8.6Hz) , 120.14 (JC–F = 23Hz) , 119.3 (JC–F = 9.5Hz) , 114.9 (JC–F = 21Hz) , 114.8 (JC–F = 21Hz) , 60.1, 55.0, 51.3, 47.2, 31.2, 31.0, 29.9, 29.4, 26.6, 26.5, 25.63, 25.58, 25.2, 25.1, 20.8, 20.6, 20.5, 20.1.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H21BrNO: 364.0683; found: 364.0680.

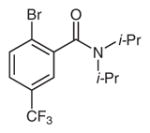

2-Bromo-N,N-diisopropyl-5-(trifluoromethyl) benzamide (11-Br)

To a 20 mL scintillation vial containing a magnetic stirbar and a solution of 2-bromo-5-trifluoromethyl benzoic acid (613 mg, 2.28 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in anhydrous toluene (8.0 mL) were added anhydrous DMF (2 drops) and SOCl2 (0.33 g, 2.77 mmol, 1.22 equiv) . The vial was sealed with a Teflon-lined cap and the reaction mixture was stirred at 80°C for 2.5 h and then cooled to r.t. to afford a solution of the intermediate 2-bromo-5-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride. Two such reactions were conducted and the solution of the 2-bromo-5-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride obtained from each reaction was combined for the next step.

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask containing a solution of N,N-diisopropylamine (693 mg, 6.85 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (23 mL) was added Et3N (1.39 g, 13.7 mmol, 3.00 equiv) under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C using an ice bath and the solution of the 2-bromo-5-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride obtained in the first step was added dropwise. The resulting mixture was stirred at r.t. for 16 h, then transferred to a separatory funnel and extracted with H2O (3×30 mL) . The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, concentrated, and purified by chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–tOAc, 80:20) to afford product 11-Br.

Yield: 582 mg (36%) ; white solid; mp 114–116°C; Rf = 0.58 (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) .

IR (neat) : 2977, 1631, 1372, 1344, 1313, 1257, 1172, 1126, 1107, 1076, 1043, 1025, 904, 845, 795, 612cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.70 (d, J = 8.3Hz, 1H) , 7.45 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2Hz, 1H) , 7.42 (d, J = 2.2, Hz, 1H) , 3.55 (sept, J = 6.9Hz, 1H) , 3.53 (sept, J = 6.7Hz, 1H) , 1.58 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 3H) , 1.57 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 3H) , 1.25 (d, J = 6.6Hz, 3H) , 1.09 (d, J = 6.7Hz, 3H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 166.7, 140.8, 133.6, 130.2 (JC–F = 33Hz) , 126.2 (JC–F = 3.6Hz) , 123.45 (JC–F = 271Hz) , 123.5 (JC–F = 3.6Hz) , 123.0, 51.4, 46.2, 20.7, 20.64, 20.56, 20.0.

HRMS: m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H17BrF3NO: 352.0518; found: 352.0523.

C–H Arylation; General Procedure

To an oven-dried 20 mL scintillation vial containing a magnetic stir bar and substrate, was added Ni(cod) 2, t-BuOK, and anhydrous THF in a glove box. The vial was sealed with a Teflon-lined cap, taken out of the glove box, and the reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for the indicated time. The reaction mixture was filtered through a 3.8cm plug of silica gel, eluting with EtOAc (100 mL) . The filtrate was concentrated and purified by chromatography on a silica gel column to afford the product.

2-Isopropyl-3,3-dimethylisoindolin-1-one (1a)

From 1-Br

Following the general procedure, 1-Br (142 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 13 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 70:30) gave 1a.

Yield: 97.8 mg (96%) ; white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.72 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 1H) , 7.45 (td, J = 7.5, 1.2Hz, 1H) , 7.34 (td, J = 7.5, 1.0Hz, 1H) , 7.29 (d, J = 7.6Hz, 1H) , 3.60 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 1.51 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) , 1.42 (s, 6H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

From 1-Cl

Following the general procedure, 1-Cl (120 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 70:30) gave 1a (95.5 mg, 94%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data was identical to the product isolated from the reaction of 1-Br.

From 1-I

Following the general procedure, 1-I (166 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) gave 1a (98.0 mg, 96%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data was identical to the product isolated from the reaction of 1-Br.

2-Isopropyl-5-methoxy-3,3-dimethylisoindolin-1-one (2a)

From 2-Br

Following the general procedure, 2-Br (157 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 18.5 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 75:25) gave 2a.

Yield: 106.9 mg (92%) ; white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.68 (d, J = 8.3Hz, 1H) , 6.92 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.2Hz, 1H) , 6.80 (d, J = 2.2Hz, 1H) , 3.87 (s, 3H) , 3.62 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 1.54 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) , 1.45 (s, 6H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

From 2-Cl

Following the general procedure, 2-Cl (135 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 12 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20 to 70:30) gave 2a (97.4 mg, 83%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data was identical to the product isolated from the reaction of 2-Br.

2-Isopropyl-3,3,5-trimethylisoindolin-1-one (3a)

Following the general procedure, 3-Br (149 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 16 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 75:25) gave 3a.

Yield: 107.7 mg (99%) ; white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.61 (d, J = 7.6Hz, 1H) , 7.16 (d, J = 7.7Hz, 1H) , 7.10 (s, 1H) , 3.59 (sept, J = 6.9Hz, 1H) , 2.40 (s, 3H) , 1.51 (d, J = 6.9Hz, 6H) , 1.42 (s, 6H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

5-Fluoro-2-isopropyl-3,3-dimethylisoindolin-1-one (4a)

From 4-Br

Following the general procedure, 4-Br (151 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 16 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) gave 4a.

Yield: 56.6 mg (51%) ; white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.72 (dd, J = 8.3, 5.1Hz, 1H) , 7.07 (td, J = 8.4, 2.1Hz, 1H) , 7.00 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.2Hz, 1H) , 3.61 (sept, J = 6.9Hz, 1H) , 1.53 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) , 1.46 (s, 6H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

From 4-Cl

Following the general procedure, 4-Cl (129 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 15 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) gave 4a (82.4 mg, 74%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data was identical to the product isolated from the reaction of 4-Br.

2′-Cyclohexylspiro(cyclohexane-1,1′-isoindolin) -3′-one (5a)

Following the general procedure, 5-Br (182 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 20 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 80:20) gave 5a.

Yield: 136.4 mg (96%) ; white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.76 (d, J = 7.0Hz, 1H) , 7.71 (d, J = 7.1Hz, 1H) , 7.43–7.34 (m, 2H) , 3.12–3.04 (m, 1H) , 2.64–2.51 (m, 2H) , 1.94–1.21 (m, 18H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

2′-Methylspiro[cyclohexane-1,1′-isoindolin]-3′-one (6a)

From 6-Br

Following the general procedure, 6-Br (148 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (27.5 mg, 0.10 mmol, 0.20 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 70:30) gave 6a.

Yield: 48.2 mg (45%) ; white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.85 (d, J = 7.0Hz, 1H) , 7.76 (d, J = 7.4Hz, 1H) , 7.47 (td, J = 7.4, 1.5Hz, 1H) , 7.42 (td, J = 7.4, 1.2Hz, 1H) , 3.01 (s, 3H) , 2.01–1.82 (m, 7H) , 1.45–1.30 (m, 3H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

From 6-I

Following the general procedure, 6-I (172 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (27.5 mg, 0.10 mmol, 0.20 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc, 70:30) gave 6a (56.1 mg, 52%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data was identical to the product isolated from the reaction of 6-Br.

2-Ethyl-3,3-dimethylisoindolin-1-one (7a)

Following the general procedure, 7-Br (135 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (27.5 mg, 0.10 mmol, 0.20 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 80:5:15) gave 7a.

Yield: 57.1 mg (60%) ; white solid; mp 90–91°C; Rf = 0.13 (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 80:5:15) .

IR (neat) : 2972, 1671, 1397, 1371, 1351, 1320, 767, 699, 689, 565cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.78 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 1H) , 7.49 (td, J = 7.4, 0.7Hz, 1H) , 7.40–7.34 (m, 2H) , 3.49 (q, J = 7.2Hz, 2H) , 1.46 (s, 6H) , 1.28 (t, J = 7.2Hz, 3H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 167.2, 151.5, 131.3, 131.0, 127.8, 123.3, 120.5, 62.6, 33.9, 25.9, 14.6.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C12H15NO: 212.1046; found: 212.1047.

2′-Isopropylspiro(cyclohexane-1,1′-isoindolin) -3′-one and 2-Cyclohexyl-3,3-dimethylisoindolin-1-one (8a and 8b)

Following the general procedure, 8-Br (162 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 85:5:10) gave a mixture of products 8a and 8b (102.1 mg, 84%) as a white solid. Note: Although the total yield is reported for the mixture of 8a and 8b, small amounts of pure 8a and 8b were isolated to obtain the following spectroscopic and HRMS data.

Isomer 8a

Rf = 0.14 (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 85:5:10) ; mp 119–120°C.

IR (neat) : 2926, 1676, 1468, 1411, 1377, 1331, 1326, 765, 700, 561cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.82–7.80 (m, 1H) , 7.75 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 7.47–7.40 (m, 2H) , 3.64 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 1.97–1.84 (m, 7H) , 1.55 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) , 1.49–1.45 (m, 2H) , 1.40–1.24 (m, 1H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 167.2, 150.1, 132.6, 130.3, 127.6, 123.2, 123.1, 65.8, 44.4, 33.0, 24.6, 22.5, 20.4.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H21NO: 266.1515; found: 266.1513.

Isomer 8b

Rf = 0.18 (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 85:5:10) ; mp 141–142°C.

IR (neat) : 2953, 2932, 2857, 1672, 1614, 1469, 1451, 1414, 1364, 1325, 764, 699cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.76 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 1H) , 7.49 (td, J = 7.4, 0.8Hz, 1H) , 7.39 (t, J = 7.6Hz, 1H) , 7.33 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 1H) , 3.18–3.10 (m, 1H) , 2.60–2.50 (m, 2H) , 1.87–1.80 (m, 2H) , 1.70–1.60 (m, 3H) , 1.47 (s, 6H) , 1.36–1.25 (m, 3H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 167.0, 151.1, 132.0, 131.1, 127.8, 123.2, 120.5, 63.3, 53.1, 30.1, 26.5, 25.5, 25.2.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H21NO: 266.1515; found: 266.1512.

6′-Fluoro-2′-isopropylspiro(cyclohexane-1,1′-isoindolin) -3′-one and 2-Cyclohexyl-5-fluoro-3,3-dimethylisoindolin-1-one (9a and 9b)

Following the general procedure, 9-Br (171 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.75 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 80:5:15) gave a mixture of products 9a and 9b (119 mg, 91%) as a white solid. Note: Although the total yield is reported for the mixture of 9a and 9b, small amounts of pure 9a and 9b were isolated to obtain the following spectroscopic and HRMS data.

Isomer 9a

Rf = 0.33 (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 80:5:15) ; mp 122–124°C.

IR (neat) : 2940, 1676, 1413, 1364, 1330, 1169, 961, 896, 884, 834, 785, 755, 695, 654cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.77 (dd, J = 8.3, 5.4Hz, 1H) , 7.43 (dd, J = 9.3, 2.1Hz, 1H) , 7.12 (td, J = 8.7, 2.2Hz, 1H) , 3.62 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 1.96–1.24 (m, 10H) , 1.54 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 166.3, 164.1 (JC–F = 248Hz) , 152.1 (JC–F = 9.0Hz) , 128.6, 125.0 (JC–F = 9.7Hz) , 115.1 (JC–F = 23Hz) , 110.9 (JC–F = 25Hz) , 65.5, 44.5, 32.9, 24.5, 22.4, 20.4.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H20FNO: 284.1421; found: 284.1425.

Isomer 9b

Rf = 0.40 (hexanes–acetone–CH2Cl2, 80:5:15) ; mp 167–168°C.

IR (neat) : 2926, 1674, 1624, 1485, 1410, 1362, 1325, 1214, 1179, 901, 890, 829, 778, 704, 693, 610cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 7.73 (dd, J = 8.3, 5.0Hz, 1H) , 7.08 (td, J = 8.8, 2.3Hz, 1H) , 7.00 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.2Hz, 1H) , 3.17–3.09 (m, 1H) , 2.57–2.47 (m, 2H) , 1.90–1.82 (m, 2H) , 1.66–1.60 (m, 3H) , 1.46 (s, 6H) , 1.31–1.25 (m, 3H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 166.1, 165.0 (JC–F = 249Hz) , 153.5 (JC–F = 8.9Hz) , 127.9, 125.3 (JC–F = 9.8Hz) , 115.5 (JC–F = 23Hz) , 108.0 (JC–F = 24Hz) , 63.0, 53.2, 30.1, 26.5, 25.4, 25.1.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H20FNO: 284.1421; found: 284.1423.

2-Isopropyl-3,3,6-trimethylisoindolin-1-one and 2-Isopropyl-3,3,4-trimethylisoindolin-1-one (10a and 10b)

Following the general procedure, 10-Cl (127 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol, 0.10 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc–CH2Cl2, 80:10:10) gave a mixture of products 10a and 10b (10a/10b = 1.1:1) . Yield: 99.5 mg (92%) ; clear oil.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ (10a) = 7.56 (s, 1H) , 7.30 (d, J = 7.7Hz, 1H) , 7.21 (d, J = 7.7Hz, 1H) , 3.62 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 2.41 (s, 3H) , 1.54 (d, J = 6.9Hz, 6H) , 1.44 (s, 6H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ (10b) = 7.62 (d, J = 7.2Hz, 1H) , 7.31–7.24 (m, 2H) , 3.63 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 2.47 (s, 3H) , 1.56 (d, J = 6.9Hz, 6H) , 1.53 (s, 6H) . The spectroscopic data is consistent with the literature.7

2-Isopropyl-3,3-dimethyl-6-(trifluoromethyl) isoindolin-1-one and 2-Isopropyl-3,3-dimethyl-4-(trifluoromethyl) isoindolin-1-one (11a and 11b)

Following the general procedure, 11-Br (176 mg, 0.500 mmol, 1.00 equiv) , Ni(cod) 2 (27.5 mg, 0.10 mmol, 0.20 equiv) , t-BuOK (84.2 mg, 0.750 mmol, 1.50 equiv) , and anhydrous THF (2.00 mL) were combined in a 20 mL scintillation vial. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 21 h. Chromatography on a silica gel column (hexanes–EtOAc–CH2Cl2, 80:10:10) gave 11a and 11b (71.3 mg, 53%) as a white solid. Note: Although the total yield is reported for the mixture of 11a and 11b, small amounts of pure 11a and 11b were isolated to obtain the following spectroscopic and HRMS data.

Isomer 11a

Rf = 0.33 (hexanes–EtOAc, 85:15) ; mp 133–135°C. IR (neat) : 2976, 1678, 1322, 1279, 1159, 1113, 1077, 1049, 907, 852, 794, 655, 631cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 8.04 (s, 1H) , 7.77 (d, J = 7.9Hz, 1H) , 7.47 (d, J = 7.9Hz, 1H) , 3.66 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 1.56 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) , 1.51 (s, 6H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 165.7, 154.4, 132.8, 130.7 (JC–F = 33Hz) , 128.1 (JC–F = 3.6Hz) , 123.9 (JC–F = 271Hz) , 121.3, 120.7 (JC–F = 3.9Hz) , 63.5, 44.8, 25.2, 20.4.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C14H16F3NO: 294.1076; found: 294.1073.

Isomer 11b

Rf = 0.28 (hexanes–EtOAc, 58:15) ; mp 55–57°C.

IR (neat) : 2977, 1686, 1422, 1380, 1370, 1352, 1307, 1234, 1159, 1121, 1081, 1066, 829, 769, 709, 615, 561cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 8.01 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 1H) , 7.80 (d, J = 7.8Hz, 1H) , 7.55 (t, J = 7.7Hz, 1H) , 3.66 (sept, J = 6.8Hz, 1H) , 1.573 (s, 6H) , 1.571 (d, J = 6.8Hz, 6H) .

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) : δ = 165.0, 147.4, 134.8, 129.5 (JC–F = 5.7Hz) , 128.4, 127.2, 124.7 (JC–F = 33Hz) , 123.9 (JC–F = 271Hz) , 65.5, 44.6, 23.7, 20.3.

HRMS: m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C14H16F3NO: 294.1076; found: 294.1072.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (R15 GM107892) and St. Olaf College.

Footnotes

This article was invited by Erick M. Carreira.

Supporting Information for this article is available online at http://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/journal/10.1055/s-00000084.

References

- 1.For some recent reviews on C–H functionalization, see: Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem Rev. 2007;107:174. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760.Kakiuchi F, Kochi T. Synthesis. 2008:3013.McGlacken GP, Bateman LM. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2447. doi: 10.1039/b805701j.Chen X, Engle KM, Wang DH, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5094. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273.Ackermann L, Vincente R, Kapdi AR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9792. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902996.Bellina F, Rossi R. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:10269.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e.Daugulis O. Top Curr Chem. 2010;292:57. doi: 10.1007/128_2009_10.Chiusoli GP, Catellani M, Costa M, Motti E, Della Ca′ N, Maestri G. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:456.Kuhl N, Hopkinson MN, Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10236. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203269.Rossi R, Bellina F, Lessi M, Manzini C. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:17.

- 2.(a) Giri R, Shi BF, Engle KM, Maguel N, Yu JQ. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3242. doi: 10.1039/b816707a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jazzar R, Hitse J, Renaudat A, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Baudoin O. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:2654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu JQ. Isr J Chem. 2010;50:605. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bellina F, Rossi R. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1082. doi: 10.1021/cr9000836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Baudoin O. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4902. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15058h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi J, Muto K, Itami K. Eur J Org Chem. 2013:19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Wang J, Ferguson DM, Kalyani D. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:5780. [Google Scholar]; (b) Muto K, Yamaguchi J, Itami K. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:169. doi: 10.1021/ja210249h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu D, Liu C, Li H, Lei A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:4453. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Aihara Y, Chatani N. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:898. doi: 10.1021/ja411715v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li ML, Dong JX, Huang XL, Li KZ, Wu Q, Song FJ, You JS. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3944. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00716f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wertjes WC, Wolfe LC, Waller PW, Kalyani D. Org Lett. 2013;15:5986. doi: 10.1021/ol402869h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For other representative reports on sp3 C–H arylation adjacent to nitrogen atoms, see: Dastbaravardeh N, Kirchner K, Schnürch M, Mihovilovic MD. J Org Chem. 2013;78:658. doi: 10.1021/jo302547q.McNally A, Prier CK, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2011;334:1114. doi: 10.1126/science.1213920.Prokopkova H, Bergman SD, Aelvoet K, Smout V, Herrebout W, Van der Veken B, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:13063. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001887.Campos KR. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1069. doi: 10.1039/b607547a.Pastine SJ, Gribkov DV, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14220. doi: 10.1021/ja064481j.Campos KR, Klapars A, Waldman JH, Dormer PG, Chem CY. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3538. doi: 10.1021/ja0605265.Snieckus V, Cuevas J-C, Sloan CP, Liu HT, Curran DP. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:896.

- 9.(a) Buden ME, Guastavino JF, Rossi RA. Org Lett. 2013;15:1174. doi: 10.1021/ol3034687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheng Y, Gu X, Li P. Org Lett. 2013;15:2664. doi: 10.1021/ol400946k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Rousseaux S, Gorelsky SI, Chung BKW, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10692. doi: 10.1021/ja103081n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rousseaux S, Davi M, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Pierre C, Kefalidis CE, Clot E, Fagnou K, Baudoin O. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10706. doi: 10.1021/ja1048847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsou TT, Kochi JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:7547. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Shirakawa E, Hayashi T. Chem Lett. 2012;41:130. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yanagisawa S, Itami K. ChemCatChem. 2011;3:827. [Google Scholar]; (c) Studer A, Curran DP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:5018. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lei A, Lei W, Liu C, Chen M. Dalton Trans. 2010:10352. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00486c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Liu W, Tian F, Wang X, Yu H, Bi Y. Chem Commun. 2013;49:2983. doi: 10.1039/c3cc40695d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mehta VP, Punji B. RSC Adv. 2013:11957. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu Y, Wong SM, Mao F, Chan TL, Kwong FY. Org Lett. 2012;14:5306. doi: 10.1021/ol302489n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bhakuni BS, Kumar A, Balkrishna SJ, Sheikh JA, Konar S, Kumar S. Org Lett. 2012;14:2838. doi: 10.1021/ol301077y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) De S, Ghosh S, Bhunia S, Sheikh JA, Bisai A. Org Lett. 2012;14:4466. doi: 10.1021/ol3019677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Shirakawa E, Itoh KI, Higashino T, Hayashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15537. doi: 10.1021/ja1080822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liu W, Cao H, Zhang H, Chung KH, He C, Wang H, Kwong FY, Lei A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16737. doi: 10.1021/ja103050x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Sun CL, Li H, Yu DG, Yu M, Zhou X, Lu XY, Huang K, Zheng SF, Li BJ, Shi ZJ. Nature Chem. 2010;2:1044. doi: 10.1038/nchem.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The mechanism in Scheme 3 is just one proposal. The regeneration of Ni0 in step (v) cannot be excluded amongst other possibilities.

- 15.We have explored the use of phenanthroline in place of Ni(cod) 2 for the room temperature arylations described in this paper. Specifically, the reaction of 1-Br or 1-Cl using phenanthroline in place of Ni(cod) 2 under otherwise identical conditions showed no product in the GC/MS trace of the crude reaction mixture. Interestingly, the arylation of 1-I using phenanthroline (0.2 equiv) , t-BuOK (1.5 equiv) , and THF did proceed at room temperature to afford 1a in 80% yield, as determined by GC/MS analysis of the crude reaction mixture against hexadecane as the internal standard. These results suggest that Ni(cod) 2 is a more effective initiator for the arylations of bromide and chloride substrates. However, either Ni(cod) 2 or phenanthroline could serve as initiator for the reaction of iodide substrates.

- 16.Bhakuni BS, Yadav A, Kumar S, Patel S, Sharma S, Kumar S. J Org Chem. 2014;79:2944. doi: 10.1021/jo402776u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.