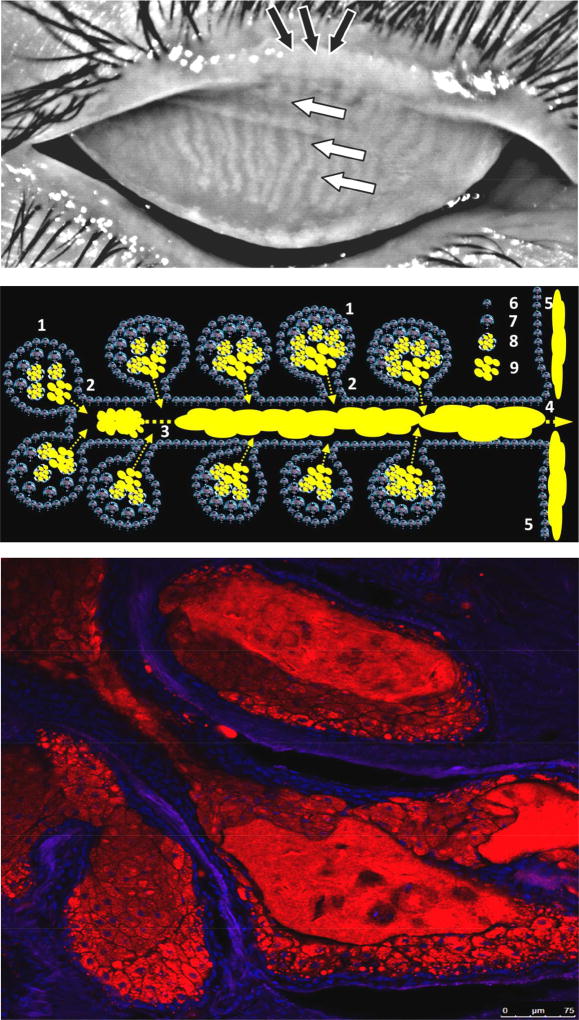

Figure 1.

Human eyelids, meibomian glands, and ascini.

Upper panel. A high-contrast photography of a human upper eyelid with normal Meibomian glands that are visible as elongated whitish structures marked with white arrows (Wojtowicz and Butovich, unpublished).

Middle panel. A schematic representation of the Meibomian gland: 1 – ascini; 2 – ductules; 3 – central duct which is being filled with meibum; 4 – orifice; 5 – secreted meibum flowing onto the lid margin and then onto ocular surface; 6 – undifferentiated Meibomian gland epithelial cells; 7 – partially differentiated meibocytes; 8 – completely differentiated, mature meibocytes with lipid droplets (yellow); 9 – lipid content released by ruptured meibocytes at the last stage of their life cycle. Note that different types of progenitor cells may exist in the glands.

Lower panel. Lipid material, stored in lipid droplets, increases in amount within meibocytes as they move towards the center of the ascinus (McMahon, Wojtowicz, and Butovich, unpublished). Following cellular disintegration, the lipid (shown in red) is observed as a bulk mass. Lipids were stained with Nile Red and imaged to detect the signals from neutral lipids (excitation 488nm, emission 500–550nm). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue). Note the virtual absence of neutral lipid staining in the basal layer of cells (only nuclei are visible) and a decreasing number of nuclei in the central parts of the ascinus (only lipid material is visible).