Abstract

A comprehensive phylogeny representing 142 described and 43 provisionally named Phytophthora species is reported here for this rapidly expanding genus. This phylogeny features signature sequences of 114 ex-types and numerous authentic isolates that were designated as representative isolates by the originators of the respective species. Multiple new subclades were assigned in clades 2, 6, 7, and 9. A single species P. lilii was placed basal to clades 1 to 5, and 7. Phytophthora stricta was placed basal to other clade 8 species, P. asparagi to clade 6 and P. intercalaris to clade 10. On the basis of this phylogeny and ancestral state reconstructions, new hypotheses were proposed for the evolutionary history of sporangial papillation of Phytophthora species. Non-papillate ancestral Phytophthora species were inferred to evolve through separate evolutionary paths to either papillate or semi-papillate species.

Keywords: oomycetes, systematics, taxonomy, evolution, plant pathology

INTRODUCTION

The genus Phytophthora has had profound impacts on human history by causing agriculturally and ecologically important plant diseases (Erwin & Ribeiro 1996). Among the most notorious Phytophthora species is P. infestans, cause of the late blight disease, which was the primary cause of the Irish potato famine from 1845 to 1852 in which approximately one million people died and 1.5 million emigrated from Ireland (Turner 2005). Another example is the sudden oak death pathogen, P. ramorum, that has killed millions of coast live oak, tanoak and Japanese larch trees, and has permanently altered the forest ecosystems in California and Oregon, USA (Goheen et al. 2002, Rizzo et al. 2002, Rizzo et al. 2005). Other species, such as P. cinnamomi, P. nicotianae, and P. sojae, can also cause highly destructive plant diseases (Erwin & Ribeiro 1996). The impact caused by Phytophthora species has continued to increase with the emergence of new pathogens and diseases. The number of species known in the genus has doubled during the past decade due to extensive surveys in previously unexplored ecosystems such as natural forests (Jung et al. 2011, 2017, Rea et al. 2010, Reeser et al. 2013, Vettraino et al. 2011), streams (Bezuidenhout et al. 2010, Brazee et al. 2017, Reeser et al. 2007, Yang et al. 2016), riparian ecosystems (Brasier et al. 2003a, 2004, Hansen et al. 2012), and irrigation systems (Hong et al. 2010, 2012, Yang et al. 2014a, b). The total number of formally named species in the genus was about 58 in 1996 (Erwin & Ribeiro 1996), but now is more than 150. In addition, some provisionally or informally named species are also expected to be formally described in the near future.

A sound taxonomic system is foundational for correctly identifying Phytophthora species and safeguarding agriculture, forestry, and natural ecosystems. Traditionally, taxonomy of the genus was based on morphological characters. A fundamental morphology-based classification of Phytophthora species was established by Waterhouse (1963) who classified the species into six groups based on the morphology of sporangia, homothallism, and configuration of antheridia. However, plasticity in morphological characters amongst isolates of individual species is significant, so is homology or homoplasy among different species. For example, isolates of P. constricta (Rea et al. 2011), P. gibbosa (Jung et al. 2011), P. lateralis (Kroon et al. 2012), P. mississippiae (Yang et al. 2013), and P. multivesiculata (Ilieva et al. 1998) all produce a mixture of semi-papillate and non-papillate sporangia. Many non-papillate species recovered from irrigation water such as Phytophthora hydropathica (Hong et al. 2010) and P. irrigata (Hong et al. 2008) were morphologically inseparable from P. drechsleri, while sequence analyses demonstrated that they are distinct species. Also, production of many morphological structures and physiological features needs specific environmental conditions, while observation of these features requires substantial training and expertise. Difficulty in obtaining important morphological data can impair accurate species identification.

With the advent of DNA sequencing, the taxonomic concept for the genus has evolved from morphology to molecular phylogeny-based (Blair et al. 2008, Cooke et al. 2000, Kroon et al. 2004, Lara & Belbahri 2011, Martin et al. 2014, Martin & Tooley 2003, Robideau et al. 2011, Villa et al. 2006). In particular, the availability of whole genome sequences from P. sojae, P. ramorum (Tyler et al. 2006) and P. infestans (Haas et al. 2009) enabled the identification of genetic markers useful for multi-locus phylogenies (Blair et al. 2008).

Cooke et al. (2000) developed the first molecular phylogeny for the genus by analyzing sequences of the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) of 51 species. Kroon et al. (2004) constructed a phylogeny based on sequences of four nuclear and mitochondrial genes of 48 species, and Blair et al. (2008) produced a sophisticated phylogeny based on sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers. That multi-locus phylogeny divided 82 Phytophthora species into 10 phylogenetically well-supported clades. Martin et al. (2014) analyzed sequences of seven nuclear and four mitochondrial genes of 90 formally named and 17 provisional species and provided phylogenies including 10 clades, almost identical to that of Blair et al. (2008), except that P. quercina and P. sp. ohioensis were excluded from clade 4 and grouped into a potentially new clade.

A comprehensive molecular phylogeny is required to understanding the evolution of Phytophthora species. Although discordance has been found between the molecular phylogeny and the morphology-based taxonomy (Cooke et al. 2000, Ersek & Ribeiro 2010), correlations have been observed between molecular phylogenies and individual morphological and physiological traits. Recent studies indicated that species in individual clades or subclades are mostly identical in sporangial papillation, and optimum and maximum growth temperatures (Cooke et al. 2000, Kroon et al. 2012, Martin et al. 2012, Yang 2014). However, there was limited to no correlation between phylogeny and the morphology of sexual organs, such as antheridial configuration (Cooke et al. 2000, Kroon et al. 2012, Martin et al. 2012, Yang 2014). These studies have implied that divergence in sporangial morphology and variation in environmental specialization may be the keys in the evolutionary history of Phytophthora species. Nevertheless, these hypotheses need to be further tested and the exact evolutionary history of the genus Phytophthora warranted more investigation.

In this study, an expanded phylogeny, including more than 180 Phytophthora taxa, many not included in any previous phylogeny, was constructed. Sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers were used for construction of the phylogeny. In light of this phylogeny, ancestral state reconstructions were conducted on the sporangial papillation of Phytophthora species. Important evolutionary divergence events and associated changes in the sporangial morphology of Phytophthora species are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolate selection

A total of 376 Phytophthora isolates representing 142 described and 43 provisionally named species, plus one isolate of each Elongisporangium undulatum (basionym: Pythium undulatum), Halophytophthora fluviatilis, and Phytopythium vexans (basionym: Pythium vexans) as outgroup taxa were included (Table 1). These included 114 ex-types (Table 2). Also included were 164 authentic isolates that were designated as representative isolates by the originators of the respective species names (Table 1). The majority of these isolates were provided by the originators of the respective species, while the rest were purchased from the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Table 1.

Information regarding isolates used in this study. GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table S1.

|

Isolate identificationd |

Isolate origins |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sub)cladea | Speciesb | Papillac | CH | CBS | ATCC | IMI | WPC | MG | Typee | Host or Substrate | Location | Year | Reference |

| 1a | P. cactorum | P | 22E6 | P10194 | p25 | Rhododendron sp. | Ohio, USA | n.a.f | (Schröter 1886) | ||||

| 22E7 | 16693 | 21168 | P0715 | p6 | n.a. | UK | n.a. | ||||||

| 22E8 | 16694, MYA-3653 | 50470 | P10193 | p7 | Malus sp. | Zimbabwe | n.a. | ||||||

| P. hedraiandra | P | 33F3 | MYA-4165 | p225 | Rhododendron sp. | Minnesota, USA | 2002 | (de Cock & Lévesque 2004) | |||||

| 38C2 | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | ||||||||||

| 62A5 | 111725 | P19523 | T | Viburnum sp. | The Netherlands | 2001 | |||||||

| P. idaei | P | 34D4 | 971.95 | MYA-4065 | 313728 | P6767 | p220 | T | Rubus idaeus | Scotland, UK | 1987 | (Kennedy & Duncan 1995) | |

| 62A1 | 968.95 | A | Rubus idaeus | Scotland, UK | 1985 | ||||||||

| P. pseudotsugae | P | 52938 | 331662 | P10339 | T | Psendotsuga menziesii | Oregon, USA | n.a. | (Hamm & Hansen 1983) | ||||

| P. aff. hedraiandra | P | 33F4 | p226 | Rhododendron sp. | Minnesota, USA | 2003 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. aff. pseudotsugae | P | 29B3 | p185 | A | Psendotsuga menziesii | Oregon, USA | 1975 | n.a. | |||||

| 1b | P. clandestina | P | 32G1 | 347.86 | 58713, 60438 | 278933 | P3943 | p200 | T | Trifolium subterraneum | Australia | 1985 | (Taylor et al. 1985) |

| 33D8 | MYA-4064 | 287317 | p215 | A | Trifolium subterranea | Australia | 1985 | ||||||

| 38D4 | p304 | n.a. | Australia | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. iranica | P | 61J4 | 374.72 | 60237 | 158964 | P3882 | p218 | T | Solanum melongena | Iran | 1969 | (Ershad 1971) | |

| P. tentaculata | P | 29F2 | 552.96 | P8497 | A | Chrysanthemum leucanthemum | Germany | n.a. | (Kröber & Marwitz 1993) | ||||

| 30D5 | Bacopa sp. | The Netherlands | 2004 | ||||||||||

| 30G8 | MYA-3655 | Argyranthemum frutescens | Germany | 2004 | |||||||||

| 1c | P. andina | SP | 60A2 | p460 | A | Solanum betaceum | Ecuador | n.a. | (Oliva et al. 2010) | ||||

| 60A3 | p461 | A | Solanum betaceum | Ecuador | n.a. | ||||||||

| P13365 | T | Solanum brevifolium | Ecuador | 2001 | |||||||||

| P. infestans | SP | 27A8 | Solanum tuberosum | Mexico | 1992 | (De Bary 1876) | |||||||

| P10650 | Solanum tuberosum | Mexico | n.a. | ||||||||||

| P. ipomoeae | SP | 31B4 | P10226 | A | Ipomoea longipedunculata | Mexico | n.a. | (Flier et al. 2002) | |||||

| 31B5 | 109229 | P10225 | T | Ipomoea longipedunculata | Mexico | 1999 | |||||||

| 31B6 | P10227 | A | Ipomoea longipedunculata | Mexico | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. mirabilis | SP | 30C1 | 64069, MYA-4062 | P3006 | p145 | A | Mirabilis jalapa | Mexico | n.a. | (Galindo-A & Hohl 1985) | |||

| 30C2 | 64070, MYA-4063 | P3007 | p153 | A | Mirabilis jalapa | Mexico | n.a. | ||||||

| P. phaseoli | SP | 23B4 | p106 | Phaseolus lunatus | Delaware, USA | 2000 | (Thaxter 1889) | ||||||

| 35B6 | Phaseolus sp. | Delaware, USA | 2000 | ||||||||||

| P10145 | Phaseolus lunatus | Delaware, USA | n.a. | ||||||||||

| P10150 | Phaseolus lunatus | Delaware, USA | n.a. | ||||||||||

| 1 | P. nicotianae | P | 22F9 | 15410, MYA-4037 | p23 | Nicotiana tabacum | North Carolina, USA | n.a. | (Breda de Haan 1896) | ||||

| 22G1 | 15409, MYA-4036 | p22 | Nicotiana tabacum | North Carolina, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| P10116 | Metrosideros excelsa | California, USA | 2002 | ||||||||||

| P1452 | Citrus sp. | California, USA | n.a. | ||||||||||

| 2a | P. botryosa | P | 22H8 | MYA-4059 | p44 | Heavae sp. | Thailand | n.a. | (Chee 1969) | ||||

| 46C2 | 26481 | p384 | A | Hevea brasiliensis | Thailand | n.a. | |||||||

| 62C6 | 581.69 | 136915 | P3425 | T | Hevea brasiliensis | Malaysia | 1966 | ||||||

| 130422 | P6945 | Hevea brasiliensis | Malaysia | 1986 | |||||||||

| P. citrophthora | P | 03E5 | p132 | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2000 | (Smith & Smith 1906) | ||||||

| 26H3 | p31 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. colocasiae | SP | 22F8 | MYA-4159 | p47 | Colocasia esculenta | n.a. | 1992 | (Raciborski 1900) | |||||

| 35D3 | p276 | Colocasia esculenta | Hawaii, USA | 2005 | |||||||||

| P. himalsilva | P | 61G2 | 128767 | T | Quercus leucotricophora | Nepal | 2005 | (Vettraino et al. 2011) | |||||

| 61G3 | 128753 | A | Quercus leucotricophora | Nepal | 2005 | ||||||||

| P. meadii | P | 22G5 | MYA-4043 | p75 | Citrus sp. | India | 1992 | (McRae 1918) | |||||

| 61J9 | 219.88 | 129185 | Hevea brasiliensis | India | 1987 | ||||||||

| P. occultans | SP | 65B9 | 101557 | T | Buxus sempervirens | The Netherlands | 1998 | (Man In’t Veld et al. 2015) | |||||

| P. terminalis | SP | 65B8 | 133865 | T | Pachysandra terminalis | The Netherlands | 2010 | (Man In’t Veld et al. 2015) | |||||

| P. aff. citrophthora | P | 26H4 | p32 | A | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| 342898 | P10341 | A | Syringa sp. | England, UK | 1990 | ||||||||

| P. aff. himalsilva | P | 61G4 | 128754 | A | Castanopsis sp. | Nepal | 2005 | n.a. | |||||

| P. sp. 46C3 | n.a. | 46C3 | 66767 | P6713 | p385 | A | Hevea brasiliensis | Malaysia | n.a. | n.a. | |||

| P. sp. P6262 | n.a. | P6262 | A | Hevea brasiliensis | India | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. P6310 | n.a. | P6310 | A | Theobroma cacao | Indonesia | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| 2b | P. capsici | P | 22F4 | 15399, MYA-4034 | p8 | A | Capsicum annum | New Mexico, USA | 1948 | (Leonian 1922) | |||

| 46012 | P0253 | Theobroma cacao | Mexico | 1964 | |||||||||

| 121656 | P10386 | Cucumis sativus | Michigan, USA | 1997 | |||||||||

| P. glovera | SP | 31E5 | p167 | A | Nicotiana tabacum | Brazil | n.a. | (Abad et al. 2011) | |||||

| 62B4 | 121969 | P11685 | T | Nicotiana tabacum | Brazil | 1995 | |||||||

| P. mengei | SP | 42B2 | MYA-4554 | p340 | T | Persea americana | California, USA | n.a. | (Hong et al. 2009) | ||||

| 42B3 | MYA-4555 | p341 | A | Persea americana | California, USA | n.a. | |||||||

| P. mexicana | P | 45G4 | 554.88 | 46731 | 92550 | P0646 | p355 | Solanum lycopersicum | Argentina | n.a. | (Hotson & Hartge 1923) | ||

| P. siskiyouensis | SP | 41B7 | 122779 | MYA-4187 | P15122 | T | Stream water | Oregon, USA | 2003 | (Reeser et al. 2007) | |||

| 41B8 | A | Soil | Oregon, USA | 2003 | |||||||||

| P. tropicalis | P | 22H5 | p27 | Vanila sp. | Tahiti | n.a. | (Aragaki & Uchida 2001) | ||||||

| 35C8 | 434.91 | 76651, MYA-4218 | p272 | T | Macadamia integrifolia | Hawaii, USA | n.a. | ||||||

| P. aff. capsici | P | 22F5 | 15427, MYA-4035 | p9 | Nicotiana tabacum | North Carolina, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| P. sp. brasiliensis | n.a. | 46705 | P0630 | A | Theobroma cacao | Brazil | 1969 | (Oudemans & Coffey 1991) | |||||

| 2c | P. acerina | SP | 61H1 | 133931 | T | Acer pseudoplatanus | Italy | 2010 | (Ginetti et al. 2014) | ||||

| 61H2 | A | Soil | Italy | 2010 | |||||||||

| P. capensis | SP | 62C1 | 128319 | P1819 | T | Curtisia dentata | South Africa | n.a. | (Bezuidenhout et al. 2010) | ||||

| 62C2 | 128320 | P1822 | A | Stream water | South Africa | n.a. | |||||||

| 62C3 | 128321 | P1823 | A | Olea campensis | South Africa | 1986 | |||||||

| P. citricola | SP | 33H8 | 221.88 | 60440 | 21173 | P0716 | p396 | T | Citrus sinensis | Taiwan | 1987 | (Sawada 1927) | |

| 33J2 | 295.29 | p375 | A | Citrus sp. | Japan | 1929 | |||||||

| P. multivora | SP | 55C5 | 124094 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2007 | (Scott et al. 2009) | |||||

| P. pachypleura | SP | 61H6 | A | Soil | UK | 2006 | (Henricot et al. 2014) | ||||||

| 61H7 | 502404 | T | Acuba japonica | UK | 2008 | ||||||||

| 61H8 | A | Soil | UK | 2009 | |||||||||

| P. pini | SP | 22F1 | MYA-3656 | p53 | A | Rhododendron sp. | West Virginia, USA | 1987 | (Hong et al. 2011) | ||||

| 45F1 | 64532 | p343 | T | Pinus resinosa | Minnesota, USA | 1925 | |||||||

| P. plurivora | SP | 22E9 | MYA-3657 | p101 | Kalmia latifolia | Western Australia, Australia | 1998 | (Jung & Burgess 2009) | |||||

| 22F2 | p52 | Rhododendron sp. cv. “Olga Mezitt” | New York, USA | n.a. | |||||||||

| 33H9 | 379.61 | Rhododendron sp. | Germany | 1958 | |||||||||

| P. sp. 22F3 | SP | 22F3 | p33 | A | n.a. | Ohio, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| P. sp. 28D1 | SP | 28D1 | p119 | A | Fagus sylvatica | New York, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| 28D3 | p121 | A | Fagus sylvatica | New York, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. sp. citricola VIII | SP | 27D9 | A | Unidentified leaf | Hainan, China | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. pini-like | SP | 56G1 | A | Taxus sp. | Pennsylvania, USA | 2011 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. taxon emzansi | SP | 61F2 | A | Agathosma betulina | South Africa | 2005 | (Bezuidenhout et al. 2010) | ||||||

| 61F3 | A | Agathosma betulina | South Africa | 2005 | |||||||||

| 2d | P. bisheria | SP | 29D2 | Rubus idaeus cv. Canby | Wisconsin, USA | 1989 | (Abad et al. 2008) | ||||||

| 31E6 | 122081 | P10117 | T | Fragaria ×ananassa | North Carolina, USA | 1999 | |||||||

| P1620 | Rhododendron sp. | North Carolina, USA | n.a. | ||||||||||

| P. elongata | SP | 33J3 | A | n.a. | Australia | 1995 | (Rea et al. 2010) | ||||||

| 33J4 | A | n.a. | Australia | 1995 | |||||||||

| 55C4 | 125799 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2004 | ||||||||

| P. frigida | P | 47G6 | A | Eucalyptus smithi | South Africa | n.a. | (Maseko et al. 2007) | ||||||

| 47G7 | A | Eucalyptus smithi | South Africa | n.a. | |||||||||

| 47G8 | T | Eucalyptus smithi | South Africa | 2001 | |||||||||

| 2e | P. multivesiculata | SP to NP | 29E3 | 545.96 | P10410 | T | Cymbidium sp. | The Netherlands | n.a. | (Ilieva et al. 1998) | |||

| 30D4 | A | Cymbidium sp. | The Netherlands | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. taxon aquatilis | SP | 38J5 | MYA-4577 | A | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | (Hong et al. 2012) | |||||

| 3 | P. ilicis | SP | 23A7 | 56615, MYA-3897 | P3939 | p113 | Ilex sp. | Canada | n.a. | (Buddenhagen & Young 1957) | |||

| 34D6 | Quercus sp. | Germany | 1999 | ||||||||||

| 62A7 | 114348 | T | Ilex aquifolium | The Netherlands | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. nemorosa | SP | 28J3 | MYA-4061 | p141 | Umbellularia californica | California, USA | n.a. | (Hansen et al. 2003) | |||||

| 41C4 | MYA-2948 | p320 | T | Lithocarpus densiflorus | California, USA | n.a. | |||||||

| P. pluvialis | SP | 60B3 | MYA-4930 | T | Rainwater | Oregon, USA | 2008 | (Reeser et al. 2013) | |||||

| P. pseudosyringae | SP | 30A8 | 111772 | MYA-4222 | p284 | T | Quercus robur | Germany | 1997 | (Jung et al. 2003) | |||

| 30B1 | Pp285 | A | Quercus robur | Germany | 1997 | ||||||||

| P. psychrophila | SP | 29J5 | 803.95 | T | Quercus robur | Germany | 1995 | (Jung et al. 2002) | |||||

| 29J6 | MYA-4083 | p288 | A | Quercus ilex | France | 1996 | |||||||

| 4 | P. alticola | P | 47G5 | 121939 | P16948 | A | Eucalyptus dunnii | South Africa | n.a. | (Maseko et al. 2007) | |||

| P. arenaria | P | 55C2 | 127950 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | (Rea et al. 2011) | |||||

| 62B7 | 125800 | A | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | ||||||||

| P. megakarya | P | 22H7 | MYA-4040 | p42 | Theobroma cacao | Africa | n.a. | (Brasier & Griffin 1979) | |||||

| 61J5 | 238.83 | 42100 | 202077 | T | Theobroma cacao | Cameroon | n.a. | ||||||

| 61J6 | 239.83 | 42099 | 106327 | A | Theobroma cacao | Nigeria | n.a. | ||||||

| P. palmivora | P | 22G8 | MYA-4039 | P10213 | p65 | Citrus sp. | Florida, USA | n.a. | (Butler 1910) | ||||

| 22G9 | MYA-4038 | p26 | Theobroma cacao | Costa Rica | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. quercetorum | P | 15C7 | Soil | South Carolina, USA | 1997 | (Balci et al. 2008) | |||||||

| 15C8 | Soil | South Carolina, USA | 1997 | ||||||||||

| P. quercina | P | 30A4 | 783.95 | A | Quercus robur | Germany | 1995 | (Jung et al. 1999) | |||||

| 30A5 | 784.95 | MYA-4084 | T | Quercus robur | Germany | 1995 | |||||||

| 30A7 | Quercus sp. | Serbia | 2003 | ||||||||||

| P. sp. ohioensis | n.a. | P16050 | A | Soil | Ohio, USA | 2006 | n.a. | ||||||

| 5 | P. agathidicida | P | 67D5 | T | Agathis australis | New Zealand | 2006 | (Weir et al. 2015) | |||||

| P. castaneae | P | 22H6 | MYA-4060 | p45 | Castanea sp. | Japan | n.a. | (Katsura 1976) | |||||

| 30E7 | Soil | Hainan, China | n.a. | ||||||||||

| 61J7 | 587.85 | 36818 | 325914 | T | Soil | Taiwan | n.a. | ||||||

| P. cocois | P | 67D6 | T | Cocos nucifera | Hawaii, USA | 1990 | (Weir et al. 2015) | ||||||

| P. heveae | P | 22J1 | 180616 | p28 | T | Heavae sp. | Malaysia | n.a. | (Thompson 1929) | ||||

| 22J2 | 16701, MYA-3895 | p17 | soil | Tennessee, USA | 1964 | ||||||||

| 6a | P. gemini | NP | 46H1 | 123382 | A | Zostera marina | The Netherlands | 1999 | (Man in’t Veld et al. 2011) | ||||

| 46H2 | 123383 | A | Zostera marina | The Netherlands | 1999 | ||||||||

| P. humicola | NP | 32F8 | 200.81 | 52179, MYA-4080 | P3826 | p198 | T | Soil | Taiwan | 1976 | (Ko & Ann 1985) | ||

| 32F9 | P6702 | p199 | A | Phaseolus vulgaris | Taiwan | n.a. | |||||||

| P. inundata | NP | 30J3 | 390121 | p291 | T | Olea sp. | Spain | 1996 | (Brasier et al. 2003b) | ||||

| 30J4 | 389751 | p298 | T | Salix matsudana | UK | 1972 | |||||||

| P8619 | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | ||||||||||

| P. rosacearum | NP | 22J9 | MYA-3662 | p82 | A | Prunus sp. | California, USA | 1987 | (Hansen et al. 2009) | ||||

| 41C1 | p321 | A | Prunus sp. | California, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| 47J1 | MYA-4456 | T | Malus domestica | California, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. sp. 48H2 | NP | 48H2 | A | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2008 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. 62C9 | NP | 62C9 | A | Stream water | Taiwan | 2013 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. personii | n.a. | P11555 | A | Nicotiana tabacum | North Carolina, USA | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| P. taxon walnut | NP | 40A7 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | (Brasier et al. 2003a) | ||||||

| 43G1 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | |||||||||

| 6b | P. amnicola | NP | 61G6 | 131652 | T | Stream water | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | (Crous et al. 2012) | ||||

| 62C5 | 133867 | Pachysandra sp. | The Netherlands | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. bilorbang | NP | 61G8 | 131653 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2010 | (Aghighi et al. 2012) | |||||

| P. borealis | NP | 60B2 | 132023 | MYA-4881 | T | Stream water | Alaska, USA | 2008 | (Hansen et al. 2012) | ||||

| P. crassamura | NP | 66C9 | A | Picea abies | Italy | 2012 | (Scanu et al. 2015) | ||||||

| 66D1 | 140357 | T | Soil | Italy | 2011 | ||||||||

| P. fluvialis | NP | 55B6 | 129424 | T | Stream water | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | (Crous et al. 2011) | |||||

| P. gibbosa | NP to SP | 55B7 | A | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | (Jung et al. 2011) | ||||||

| 62B8 | 127951 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | ||||||||

| P. gonapodyides | NP | 21J5 | 46726 | p117 | Water | England, UK | n.a. | (Buisman 1927, Petersen 1910) | |||||

| 34A8 | 554.67 | 60351 | P6872 | Reservoir water | n.a. | 1967 | |||||||

| P. gregata | NP | 55B8 | A | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | (Jung et al. 2011) | ||||||

| 62B9 | 127952 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2009 | ||||||||

| P. lacustris | NP | 61D6 | A | Soil | Germany | 2003 | (Nechwatal et al. 2013) | ||||||

| 61D8 | A | Soil | Germany | 2003 | |||||||||

| NP | 61E1 | A | Soil | Germany | 2006 | ||||||||

| 389725 | P10337 | T | Salix matsudana | England, UK | 1972 | ||||||||

| P. litoralis | NP | 55B9 | 127953 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2008 | (Jung et al. 2011) | |||||

| P. megasperma | NP | 62C7 | 402.72 | 58817 | 32035 | P3599 | T | Althaea rosea | Washington DC, USA | 1931 | (Drechsler 1931) | ||

| P. mississippiae | NP to SP | 57J1 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | (Yang et al. 2013) | ||||||

| 57J2 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| 57J3 | MYA-4946 | T | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | ||||||||

| 57J4 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| P. ornamentata | NP | 66D2 | 140647 | T | Soil | Italy | 2012 | (Scanu et al. 2015) | |||||

| 66D3 | A | Soil | Italy | 2012 | |||||||||

| P. pinifolia | NP | 47H1 | 122924 | T | Pinus radiata | Chile | 2007 | (Duran et al. 2008) | |||||

| 47H2 | 122922 | A | Pinus radiata | Chile | 2007 | ||||||||

| P. riparia | NP | 60B1 | 132024 | MYA-4882 | T | Stream water | Oregon, USA | 2006 | (Hansen et al. 2012) | ||||

| P. thermophila | NP | 55C1 | 127954 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2004 | (Jung et al. 2011) | |||||

| P. ×stagnum | NP | 36H8 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | (Yang et al. 2014c) | ||||||

| 36J7 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | |||||||||

| 43F3 | MYA-4926 | T | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | ||||||||

| 44F9 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | |||||||||

| P. sp. 26E1 | NP | 26E1 | p116 | A | Malus domestica | New York, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| P. sp. canalensis | n.a. | P10456 | A | Canal water | California, USA | 2002 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. delaware | NP | 63H4 | A | Pond water | Delaware, USA | 2014 | n.a. | ||||||

| 63H7 | A | Pond water | Delaware, USA | 2014 | |||||||||

| P. sp. gregata-like | NP | 22J5 | 16698 | p16 | A | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | ||||

| P. sp. megasperma-like | NP | 23A1 | p81 | A | Prunus sp. | California, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| 23A3 | MYA-3660 | p79 | A | Actinidia chinensis | California, USA | 1987 | |||||||

| 6 | P. asparagi | NP | 33D7 | 384046 | A | Asparagus officinalis | New Zealand | 1980 | (Crous et al. 2012) | ||||

| 62C4 | 132095 | MYA-4826 | T | Asparagus officinalis | Michigan, USA | 2006 | |||||||

| P. sp. sulawesiensis | n.a. | P6306 | A | Syzygium aromaticum | Indonesia | 1989 | n.a. | ||||||

| 7a | P. attenuata | NP | 67C5 | T | Soil | Taiwan | 2013 | (Jung et al. 2017) | |||||

| P. europaea | NP | 30A3 | Quercus sp. | France | 1998 | (Jung et al. 2002) | |||||||

| 34C2 | Quercus sp. | Germany | 1999 | ||||||||||

| 62A2 | 109049 | T | Soil | France | 1998 | ||||||||

| P. flexuosa | NP | 67C3 | T | Soil | Taiwan | 2013 | (Jung et al. 2017) | ||||||

| P. formosa | NP | 67C4 | T | Soil | Taiwan | 2013 | (Jung et al. 2017) | ||||||

| P. fragariae | NP | 22G6 | 11374 | P3570 | p114 | Fragaria ×ananassa | Maryland, USA | n.a. | (Hickman 1940) | ||||

| 30C5 | Fragaria ×ananassa | Virginia, USA | n.a. | ||||||||||

| 61J3 | 209.46 | 181417 | P6231 | T | Fragaria ×ananassa | England, UK | n.a. | ||||||

| P. intricata | NP | 67B9 | T | Soil | Taiwan | 2013 | (Jung et al. 2017) | ||||||

| P. rubi | NP | 30D7 | p186 | A | Rubus sp. | Australia | n.a. | (Man in ‘t Veld 2007) | |||||

| 41D5 | Rubus sp. | Norway | 2005 | ||||||||||

| 46C7 | 90442 | p389 | T | Rubus idaeus cv. "Glen Clova" | Scotland, UK | n.a. | |||||||

| P. uliginosa | NP | 62A3 | 109054 | P10413 | T | Soil | Poland | 1998 | (Jung et al. 2002) | ||||

| 62A4 | 109055 | P10328 | A | Soil | Germany | 1998 | |||||||

| P. ×alni | NP | 32J6 | 392317 | MYA-4081 | p205 | A | Alnus glutinosa | France | 1996 | (Brasier et al. 2004, Husson et al. 2015) | |||

| 32J7 | 392318 | p206 | A | Alnus sp. | Austria | 1996 | |||||||

| 47A7 | 392314 | T | Alnus sp. | UK | 1994 | ||||||||

| 47A8 | A | Alnus sp. | The Netherlands | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. ×cambivora | NP | 22F6 | 46719, MYA-4076 | p64 | Abies sp. | Oregon, USA | n.a. | (Buisman 1927, Jung et al. 2017) | |||||

| 26F8 | MYA-4075 | p38 | n.a. | New York, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. ×heterohybrida | NP | 67C1 | T | Stream water | Taiwan | 2013 | (Jung et al. 2017) | ||||||

| P. ×incrassata | NP | 67C2 | T | Stream water | Taiwan | 2013 | (Jung et al. 2017) | ||||||

| P. sp. europaea SW | NP | 33F7 | p229 | A | Soil | West Virginia, USA | 2005 | n.a. | |||||

| 7b | P. asiatica | NP | 45G1 | 90455 | p352 | A | Robinia pseudoacacia | Jiangsu, China | n.a. | (Rahman et al. 2014a) | |||

| 46C6 | 56194 | p388 | A | Robinia pseudoacacia | Jiangsu, China | n.a. | |||||||

| 61H3 | 133347 | T | Pueraria lobata | Japan | 2005 | ||||||||

| P. cajani | NP | 33D9 | p214 | Cajanus cajani | India | n.a. | (Amin et al. 1978) | ||||||

| 45F6 | 44389 | p348 | A | Cajanus cajani | India | n.a. | |||||||

| 45F7 | 44388 | P3105 | p349 | T | Cajanus cajani | India | n.a. | ||||||

| P. melonis | NP | 32F6 | MYA-4079 | P1371 | p196 | A | Cucumis sativus | China | n.a. | (Katsura 1976) | |||

| 41B4 | p318 | A | Cucumis sativus | Iran | n.a. | ||||||||

| 45F3 | 582.69 | 52854 | T | Cucumis sativus | Japan | n.a. | |||||||

| P. niederhauserii | NP | 01D5 | p312 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2000 | (Abad et al. 2014) | |||||

| 23J6 | MYA-4163 | p57 | A | Unknown ornamental | Israel | n.a. | |||||||

| 31E7 | P10617 | p169 | A | Thuja occidentalis | North Carolina, USA | 2001 | |||||||

| P. pisi | NP | 60A4 | T | Pea | Sweden | 2009 | (Heyman et al. 2013) | ||||||

| 60A5 | A | Pea | Sweden | 2009 | |||||||||

| P. pistaciae | NP | 33D6 | MYA-4082 | 386658 | p216 | T | Pistacia vera | Iran | 1986 | (Mirabolfathy et al. 2001) | |||

| 41A9 | p314 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. sojae | NP | 22D8 | 312.62 | 16705, MYA-3899 | 131375 | p19 | Glycine max | Ontario, Canada | 1959 | (Kaufmann & Gerdemann 1958) | |||

| 28F9 | p236 | Glycine max | Mississippi, USA | 1970 | |||||||||

| P. vignae | NP | 45G6 | 46735 | p357 | A | Glycine max | n.a. | n.a. | (Purss 1957) | ||||

| 45G9 | 64832 | 316196 | P3420 | p379 | Vigna unguiculata | Sri Lanka | n.a. | ||||||

| 46C1 | 112.76 | 64129 | p380 | Vigna sinensis | n.a. | n.a. | |||||||

| 7c | P. cinnamomi | NP | 23B1 | 15400, MYA-4057 | p10 | Camellia japonica | South Carolina, USA | n.a. | (Rands 1922) | ||||

| 23B2 | 15401, MYA-4058 | p11 | Persea americana | Puerto Rico | 1960 | ||||||||

| 61J1 | 144.22 | 46671 | 22938 | P2110 | T | Cinnamomum burmannii | Indonesia | 1922 | |||||

| P. parvispora | NP | 30G9 | MYA-4078 | p178 | A | Beaucarnea sp. | Germany | 1991 | (Scanu et al. 2014) | ||||

| 46F6 | A | Beaucarnea sp. | Germany | 1992 | |||||||||

| 66C7 | 132771 | A | Arbutus unedo | Italy | 2008 | ||||||||

| 66C8 | 132772 | T | Arbutus unedo | Italy | 2011 | ||||||||

| P. sp. ax | NP | 46H5 | A | Ilex glabra cv. “Shamrock” | Virginia, USA | 2008 | n.a. | ||||||

| 7d | P. fragariaefolia | NP | 61H4 | 135747 | T | Fragaria ×ananassa | Japan | 2005 | (Rahman et al. 2014b) | ||||

| P. nagaii | NP | 61H5 | 133248 | T | Rosa sp. | Japan | 1968 | (Rahman et al. 2014b) | |||||

| 8a | P. cryptogea | NP | 61H9 | 113.19 | 180615 | P1738 | T | Solanum lycopersicum | Ireland | n.a. | (Pethybridge & Lafferty 1919) | ||

| P. drechsleri | NP | 15E5 | Soil | South Carolina, USA | 1997 | (Tucker 1931) | |||||||

| 15E6 | Soil | South Carolina, USA | 1998 | ||||||||||

| 23J5 | 292.35 | 46724 | P1087 | p41 | T | Beta vulgaris var. altissima | California, USA | n.a. | |||||

| P10331 | Gerbera jamesonii | New Hampshire, USA | 2003 | ||||||||||

| P. erythroseptica | NP | 61J2 | 129.23 | 34684 | P1693 | T | Solanum tuberosum | Ireland | n.a. | (Pethybridge 1913) | |||

| P. medicaginis | NP | 23A4 | MYA-3900 | p37 | Medicago sativa | Ohio, USA | n.a. | (Hansen & Maxwell 1991) | |||||

| 28F1 | 44390 | P1057 | p124 | Medicago sativa | California, USA | 1975 | |||||||

| P. pseudocryptogea | NP | 52402 | P3103 | Solanum marginatum | Ecuador | n.a. | (Safaiefarahani et al. 2015) | ||||||

| P. richardiae | NP | 31E8 | P10355 | p170 | Zantedeschia sp. | Japan | 1989 | (Buisman 1927) | |||||

| 45F5 | 240.30 | 60353, 46734 | 325930 | p347 | T | Zantedeschia aethiopica | USA | n.a. | |||||

| P10811 | Zantedeschia aethiopica | Japan | 1989 | ||||||||||

| P. sansomeana | NP | 47H3 | MYA-4455 | T | Glycine sp. | Indiana, USA | n.a. | (Hansen et al. 2009) | |||||

| 47H4 | A | Glycine sp. | Indiana, USA | n.a. | |||||||||

| 47H5 | A | Glycine sp. | Indiana, USA | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. trifolii | NP | 29B2 | MYA-3901 | p142 | A | Trifolium vesiculosum | Mississippi, USA | 1978 | (Hansen & Maxwell 1991) | ||||

| 62A9 | 117687 | T | Trifolium sp. | Mississippi, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| P. aff. cryptogea | NP | 22G2 | 308.62 | 15402, MYA-4161 | 325907 | p12 | Aster sp. | California, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||

| P. aff. erythroseptica | NP | 22J4 | MYA-4041 | p50 | n.a. | Ohio, USA | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| 33A1 | p207 | Solanum tuberosum | Maine, USA | 2004 | |||||||||

| P. sp. kelmania | NP | 24A7 | MYA-4162 | p102 | A | Abies concolor | West Virginia, USA | 1998 | n.a. | ||||

| 31E4 | P10613 | p166 | A | Abes fraseri | North Carolina, USA | 2002 | |||||||

| 8b | P. brassicae | SP | 29D8 | 686.95 | A | Brassica oleracea | The Netherlands | 1995 | (Man in’t Veld et al. 2002) | ||||

| 61J8 | 179.87 | P7517, P19521 | T | Brassica oleracea | The Netherlands | 1986 | |||||||

| P. cichorii | SP | 62A8 | 115029 | T | Cichorium intybus var. foliosum | The Netherlands | 2004 | (Bertier et al. 2013) | |||||

| P. dauci | SP | 61E5 | 127102 | T | Daucus carota | France | 2009 | (Bertier et al. 2013) | |||||

| 32E5 | Duscus carota | France | 2004 | ||||||||||

| 32E6 | P10728 | Duscus carota | France | 2004 | |||||||||

| 32E7 | p194 | Duscus carota | France | 2004 | |||||||||

| P. lactucae | SP | 61F4 | T | Lactuca sativa | Greece | 2001 | (Bertier et al. 2013) | ||||||

| 61F7 | A | Lactuca sativa | Greece | 2002 | |||||||||

| 61F8 | A | Lactuca sativa | Greece | 2003 | |||||||||

| P. primulae | SP | 29E9 | 620.97 | p286 | Primula acaulis | Germany | 1997 | (Tomlinson 1952) | |||||

| 29F1 | p287 | Primula sp. | The Netherlands | 1998 | |||||||||

| P. aff. brassicae-2 | n.a. | 112968 | P6207 | A | Allium cepa | Switzerland | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| P. aff. cichorii | SP | 61E3 | 133815 | A | Cichorium intybus var. foliosum | UK | 1999 | n.a. | |||||

| P. sp. 29E7 | SP | 29E7 | A | Allium porrum | The Netherlands | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| P. taxon castitis | SP | 61E7 | 131246 | A | Fragaria ×ananassa | Sweden | 1995 | (Bertier et al. 2013) | |||||

| P. taxon parsley | SP | 61G1 | A | Petroselinum crispum | Greece | 2006 | (Bertier et al. 2013) | ||||||

| 8c | P. foliorum | SP | 49J8 | 121655 | MYA-3638 | P10974 | T | Rhododendron sp. | Tennessee, USA | 2004 | (Donahoo et al. 2006) | ||

| P. hibernalis | SP | 22H1 | 270.31 | 60352 | 36906 | P6871 | p115 | Citrus sinensis | Portugal | 1931 | (Carne 1925) | ||

| 32F7 | 114104 | 56353, MYA-3896 | 134760 | P3822 | p197 | Citrus sinensis | Western Australia, Australia | 1958 | |||||

| P. lateralis | NP to SP | 22H9 | MYA-3898 | p51 | A | Chamaecyparis lawsoniana | Oregon, USA | n.a. | (Tucker & Milbrath 1942) | ||||

| 29A9 | 201856 | p128 | Chamaecyparis lawsoniana | California, USA | 1997 | ||||||||

| P. ramorum | SP | 32G2 | Camellia japonica | South Carolina, USA | n.a. | (Werres et al. 2001) | |||||||

| 33F2 | Quercus agrifolia | California, USA | n.a. | ||||||||||

| 8d | P. austrocedrae | SP | 41B5 | MYA-4073 | A | Austrocedrus chilensis | Argentina | n.a. | (Greslebin et al. 2007) | ||||

| 41B6 | 122911 | MYA-4074 | T | Austrocedrus chilensis | Argentina | 2005 | |||||||

| P. obscura | SP | 60E9 | 129273 | T | Soil | Germany | 1994 | (Grünwald et al. 2012) | |||||

| 60F1 | A | Pieris sp. | Oregon, USA | 2009 | |||||||||

| 60F2 | A | Kalmia latifolia | Oregon, USA | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. syringae | SP | 21H9 | 34002 | P0649 | p187 | Citrus sp. | California, USA | n.a. | (Klebahn 1905) | ||||

| 23A6 | MYA-3659 | p35 | n.a. | New York, USA | n.a. | ||||||||

| 8 | P. stricta | NP | 58A1 | MYA-4944 | T | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | (Yang et al. 2014a) | ||||

| 58A2 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| 58A3 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| 58A4 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| 9a (cluster 9a1) | P. aquimorbida | NP | 40A6 | MYA-4578 | T | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | (Hong et al. 2012) | ||||

| 40E3 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | |||||||||

| 44G9 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | |||||||||

| P. chrysanthemi | NP | 61E9 | A | Chrysanthemum sp. | Japan | 1998 | (Naher et al. 2011) | ||||||

| 61F1 | 123163 | T | Chrysanthemum ×morifolium | Japan | 2000 | ||||||||

| P. hydrogena | NP | 44G8 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | (Yang et al. 2014b) | ||||||

| 46A3 | MYA-4919 | T | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | ||||||||

| 46A4 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | |||||||||

| P. hydropathica | NP | 05D1 | MYA-4460 | p366 | T | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2000 | (Hong et al. 2010) | ||||

| 5C11 | MYA-4459 | p365 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2000 | |||||||

| P. irrigata | NP | 04E4 | MYA-4458 | p335 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2000 | (Hong et al. 2008) | ||||

| 23J7 | MYA-4457 | p108 | T | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2000 | |||||||

| 44E4 | A | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | |||||||||

| P. macilentosa | NP | 58A5 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | (Yang et al. 2014a) | ||||||

| 58A6 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| 58A7 | MYA-4945 | T | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | ||||||||

| 58A8 | A | Irrigation water | Mississippi, USA | 2012 | |||||||||

| P. parsiana | NP | 47C3 | 395329 | T | Ficus carica | Iran | 1991 | (Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa et al. 2008) | |||||

| P. virginiana | NP | 40A9 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | (Yang & Hong 2013) | ||||||

| 44G6 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | |||||||||

| 46A2 | MYA-4927 | T | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | ||||||||

| P. aff. parsiana G1 | NP | 47C7 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| 47C8 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | |||||||||

| 395328 | P8618 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | 1992 | ||||||||

| P. aff. parsiana G2 | NP | 47C5 | 395330 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | 1992 | n.a. | |||||

| 47C6 | 395331 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | 1992 | ||||||||

| P. aff. parsiana G3 | NP | 47D5 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| 47D8 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | |||||||||

| 47E1 | A | Pistacia vera | Iran | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. sp. 35G4 | NP | 35G4 | A | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2005 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. 38D9 | NP | 38D9 | A | Dianthus caryophyllus | Taiwan | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. 40J5 | NP | 40J5 | A | Unknown leaf in seawater | Hainan, China | n.a. | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. cuyabensis | n.a. | P8213 | A | n.a. | Ecuador | 1993 | n.a. | ||||||

| P. sp. lagoariana | NP | 60B4 | P8220 | A | n.a. | Ecuador | n.a. | n.a. | |||||

| 60B5 | P8217 | T | n.a. | Ecuador | n.a. | ||||||||

| P8223 | A | n.a. | Ecuador | 1993 | |||||||||

| 9a (cluster 9a2) | P. macrochlamydospora-G1 | SP | 33E1 | P10264 | Glycine max | New South Wales, Australia | n.a. | (Irwin 1991) | |||||

| P10267 | Glycine max | New South Wales, Australia | 1994 | ||||||||||

| P. macrochlamydospora-G2 | SP | 31E9 | 351473 | P8017 | p171 | Glycine max | Queensland, Australia | n.a. | (Irwin 1991) | ||||

| 33D5 | 240.30 | 60353 | 340618 | Zantedeschia aethiopica | The Netherlands | 1927 | |||||||

| P. quininea | NP | 45F2 | 406.48 | 56964 | p344 | A | Cinchona officinalis | Peru | n.a. | (Crandall 1947) | |||

| 46C4 | 407.48 | 46733 | p386 | T | Cinchona officinalis | Peru | n.a. | ||||||

| 9a (cluster 9a3) | P. insolita | NP | 327E1 | MYA-4077 | p123 | Waterfall water | Hainan, China | n.a. | (Ann & Ko 1980) | ||||

| 38E1 | 691.79 | 38789 | 288805 | T | Soil | Taiwan | 1980 | ||||||

| P6703 | A | Soil | Taiwan | n.a. | |||||||||

| P. polonica | NP | 40G9 | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2006 | (Belbahri et al. 2006) | |||||||

| 43F9 | Irrigation water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | ||||||||||

| 49J9 | P15005 | A | Soil | Poland | 2006 | ||||||||

| 9b | P. captiosa | NP | 46H6 | A | Eucalyptus saligna | New Zealand | 1999 | (Dick et al. 2006) | |||||

| 46H7 | P10719 | T | Eucalyptus saligna | New Zealand | 1992 | ||||||||

| 46H8 | A | Eucalyptus saligna | New Zealand | 2000 | |||||||||

| P10721 | A | Eucalyptus saligna | New Zealand | 1998 | |||||||||

| P. constricta | NP to SP | 55C3 | 125801 | T | Soil | Western Australia, Australia | 2006 | (Rea et al. 2011) | |||||

| P. fallax | NP | 46J2 | P10722 | T | Eucalyptus delegatensis | New Zealand | 1997 | (Dick et al. 2006) | |||||

| 46J3 | A | Eucalyptus nitens | New Zealand | 2000 | |||||||||

| 46J5 | A | Eucalyptus nitens | New Zealand | 2000 | |||||||||

| P10725 | A | Eucalyptus fastigata | New Zealand | 2004 | |||||||||

| 10 | P. boehmeriae | P | 45F9 | 291.29 | 180614 | P6950 | T | Boehmeriae nivea | Taiwan | 1927 | (Sawada 1927) | ||

| P. gallica | NP | 50A1 | 111474 | P16826 | T | Quercus robur | France | 1998 | (Jung & Nechwatal 2008) | ||||

| 61D5 | 111475 | P16827 | A | Phragmites australis | Germany | 2004 | |||||||

| P. gondwanensis | P | 22G7 | MYA-3893 | n.a. | Ohio, USA | n.a. | (Crous et al. 2015) | ||||||

| P. intercalaris | NP | 45B7 | 140632 | TSD-7 | T | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2007 | (Yang et al. 2016) | ||||

| 48A1 | A | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2008 | |||||||||

| 49A7 | 140631 | A | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2009 | ||||||||

| P. kernoviae | P | 46C8 | P10956 | p390 | Rhododendron ponticum | England, UK | 2004 | (Brasier et al. 2005) | |||||

| 46J6 | P10681 | Annona cherimola | New Zealand | 2002 | |||||||||

| 46J8 | P10671 | Soil | New Zealand | 2003 | |||||||||

| P. morindae | P | 62B5 | 121982 | T | Morinda citrifolia var. citrifolia | Hawaii, USA | 2005 | (Nelson & Abad 2010) | |||||

| P. sp. boehmeriae-like | P | 45F8 | 357.52 | 60173 | 32199 | P1378 | p350 | A | Citrus sinensis | Argentina | 1939 | n.a. | |

| n.a. | P. lilii | NP | 135746 | T | Lilium sp. | Japan | 1987 | (Rahman et al. 2015) | |||||

| outgroup | Elongisporangium undulatum | P | 101728 | 337230 | P10342 | T | Larix sp. | Scotland, UK | 1989 | (Uzuhashi et al. 2010) | |||

| Phytopythium vexans | P | 340.49 | 12194 | P3980 | T | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | (de Cock et al. 2015) | ||||

| Halophytophthora fluviatilis | P | 57A9 | MYA-4961 | T | Stream water | Virginia, USA | 2011 | (Yang & Hong 2014) | |||||

a Molecular (sub)clade as designated in Fig. 1

b Names of taxa informally designated for the first time in this study are underlined.

c Sporangial papillation: NP = non-papillate, P = papillate, and SP = semi-papillate.

d Isolate identification abbreviations: CH, Chuanxue Hong laboratory at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA; CBS, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; IMI, CABI Biosciences, UK; WPC, the World Phytophthora Genetic Resource Collection at University of California, Riverside, USA; MG, Mannon E. Gallegly laboratory at West Virginia University, USA. Local identifications of respective isolates are provided in Table S1.

e Ex-types (T) or authentic (A) isolates (designated as representative isolates by the originators of the respective species).

f n.a.= not available.

Table 2.

Numbers of species and ex-types included in phylogenies for the genus Phytophthora in previous studies and this study.

|

Number of species |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogeny in | Formal | Provisional | Number of ex-types |

| Cooke et al. (2000) | 49 | 2 | 9 |

| Kroon et al. (2004) | 46 | 2 | 18 |

| Blair et al. (2008) | 72 | 10 | 16 |

| Martin et al. (2014) | 90 | 17 | 31 |

| This study | 142 | 43 | 114 |

DNA extraction

To extract genomic DNA (gDNA), an approximately 5 × 5 mm culture plug of each isolate was taken from the actively growing area of a fresh culture. This was then grown in 20 % clarified V8 broth (lima bean broth for growing a P. infestans isolate 27A8) at room temperature (ca. 23 °C) for 7–14 d to produce a mycelial mass. The mass was then blot-dried using sterile tissue paper and then lysed in liquid nitrogen or using a FastPrep®-24 system (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA). gDNA was extracted using the DNeasy® Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or the Maxwell® Plant DNA kit in combination with a Maxwell® Rapid Sample Concentrator (Promega, Madison, WI).

DNA amplification and sequencing

A set of primers for seven genetic markers were used for DNA amplification including 60S Ribosomal protein L10 (60S), beta-tubulin (Btub), elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1α), enolase (Enl), heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), 28S ribosomal DNA (28S), and tigA gene fusion protein (TigA) as indicated in Blair et al. (2008). PCR reaction mixtures were prepared with the Takara Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR cycling protocol was the same as indicated by Blair et al. (2008), except that the Eppendorf® Mastercycler® Pro thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg) was used in this study. All PCR products were evaluated for successful amplification using agarose gel electrophoresis. Unsuccessful PCR amplifications were repeated using a modified protocol to attempt successful amplifications by optimizing annealing temperature using gradient PCR (typically with lower annealing temperatures) or using the GoTaq® Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) PCR mixture system.

Prior to sequencing, excess primer and dNTPs were removed from successful PCR products with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I (USB Catalog # 70092Y and 70073Z). One unit of each enzyme was added to 15 μL PCR product, incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by heat inactivation at 65 °C for 15 min. Sequencing was performed with both amplifying primers as well as internal primers, if any, for individual genetic markers at the University of Kentucky Advanced Genetic Technologies Center (Lexington, KY). Derived sequencing files were visualized with FinchTV version 1.4.0 (Geospiza, Seattle, WA). Sequences of each isolate with all primers for individual genetic markers were aligned with Clustal W (Larkin et al. 2007) and edited manually to correct obvious sequencing errors and code ambiguous sites according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nucleotide ambiguity codes to produce a consensus sequence. All sequences produced in this study have been deposited in GenBank (Supplementary Table 1).

Among 379 isolates (including three isolates of the outgroup taxa) in the following phylogenetic analyses, all seven phylogenetic markers from 321 isolates were sequenced in this study. Sequences of all markers from 49 isolates by Blair et al. (2008) were also included in the analyses. Additionally, for seven isolates, sequences of one or two genes were newly produced in this study while the remaining gene sequences were from Blair et al. (2008). Sequences from P. lilii (CBS 135746) and P. sp. ohioensis (ST18-37) were obtained from Rahman et al. (2015) and from the Phytophthora Database (Park et al. 2013), respectively.

Phylogenetic analyses

Concatenated sequences of all isolates were aligned using Clustal X version 2.1 (Larkin et al. 2007). The alignment was edited in BioEdit version 7.2.5 (Hall 1999) to trim aligned concatenated sequences to an equal size and set missing data to question marks. The edited alignment was then analyzed in jModelTest version 2.1.7 (Posada 2008) to select the most appropriate model for the following phylogenetic analyses. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was performed using RAxML version 8.2.0 (Stamatakis 2014) with the selected model and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Maximum parsimony (MP) analysis was conducted using PAUP version 4.0a147 (Swofford 2002) with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Bayesian analysis (BA) was performed using MrBayes version 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al. 2012) for two million generations with the selected model. Phylogenetic trees were viewed and edited in FigTree version 1.4.2. Alignment and phylogenetic trees from all methods have been deposited in TreeBASE (S19303).

Ancestral character state reconstructions of sporangial papillation

Information on the sporangial papillation of individual species was compiled from the literature (Erwin & Ribeiro 1996, Gallegly & Hong 2008, Kroon et al. 2012, Martin et al. 2012) with emphasis given to their respective original descriptions (Table 1). Both likelihood and parsimony ancestral state reconstructions were performed on the ML tree from the phylogenetic analyses using Mesquite version 3.03 (Maddison & Maddison 2017).

RESULTS

Sequences, alignment, and phylogenetic model

PCR amplification and sequencing was successful for almost all isolates and seven genetic markers. Failure to obtain sequences only occurred occasionally for a few isolates, such as the EF1α gene of Phytophthora bilorbang (61G8), the Enl gene of P. macrochlamydospora (33E1, 31E9, and 33D5), and P. quininea (45F2), and TigA of P. megasperma (62C7) (Supplementary Table 1). These failures were set as missing data in the alignment. After trimming, each isolate was represented by an 8435-bp concatenated sequence in the alignment including gaps and missing data. This included 496 bp for 60S, 1136 bp for Btub, 965 bp for EF1α, 1169 bp for Enl, 1758 bp for HSP90, 1270 bp for 28S, and 1641 bp for TigA (TreeBASE S19303). The general time reversible nucleotide substitution model with gamma-distributed rate variation and a proportion of invariable sites (GTR+I+G) was identified by jModelTest as the most appropriate model for the phylogenetic analyses.

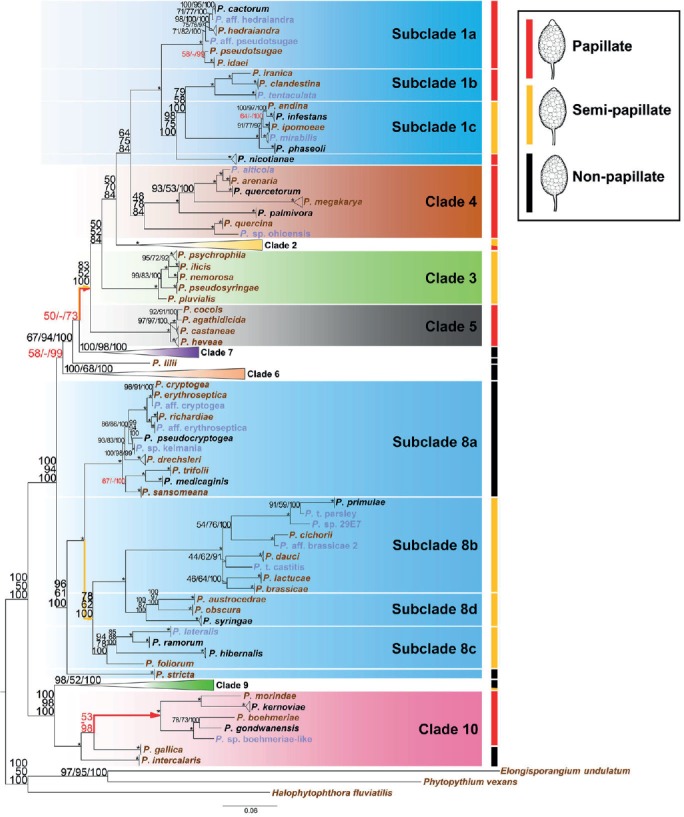

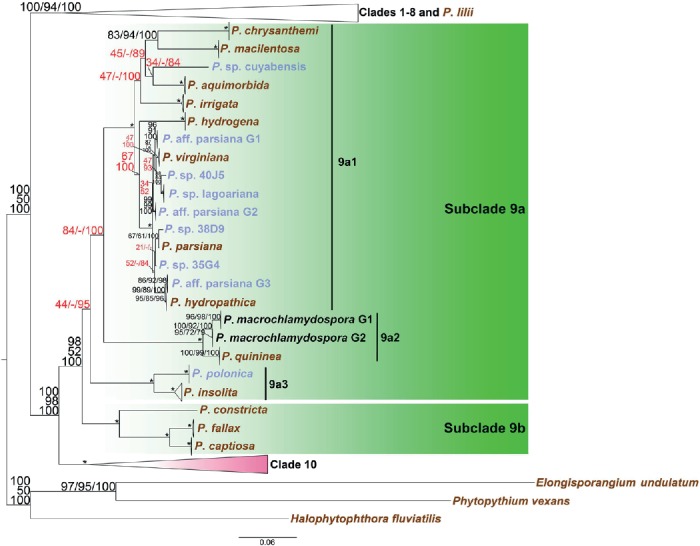

An expanded phylogeny including 10 clades and basal taxa

The three phylogenetic analysis methods, including ML, MP, and BA analyses (TreeBASE S19303), resulted in similar tree topologies. The topology and branch lengths of the ML inference are shown in Fig. 1. The monophyly of each of the previously recognized 10 clades was generally well supported with a few exceptions. Specifically, all clades except for clade 4 were highly supported by > 95 % bootstrap values in ML analysis and 100 % posterior probability (PP) in BA analysis (Fig. 1). Clades 1–3, 5, 7, and 10 were also highly supported by > 95 % bootstrap values in the MP analysis (Fig. 1). However, clades 6, 8, and 9, were only moderately supported with bootstrap numbers of 68, 61, and 52 in the MP analysis, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora based on concatenated sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers. Topology and branch lengths of maximum likelihood analysis are shown. Bootstrap values for maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (percentages) are indicated on individual nodes and separated by a forward slash. An asterisk is used in place of nodes with unambiguous (100 %) support in all three analyses. A dash is used in place of a topology from an analysis ambiguous to the other two analyses and these sets of numbers with ambiguity in one analysis are also highlighted in red. Detailed structures of clades 2, 6, 7, and 9 are shown in Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, respectively. Species represented by ex-types and authentic isolates are written in brown and blue, respectively. Branches indicating three hypothesized evolutionary paths with all species producing papillate or semi-papillate sporangia are drawn in red or orange, respectively. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site.

As nearly half of all taxa included in this phylogeny were recently described, all clades in this phylogeny are expanded here to various extents compared to previously published phylogenies. The general structure of clades 1, 3, 5, 8 and 10 remained as previously assigned by Blair et al. (2008) and Martin et al. (2014) with additions of new species. For example, clade 1 was divided into three well-supported subclades and P. nicotianae was placed basal to subclades 1b and 1c (Fig. 1). Clade 8 was divided into four generally well-supported subclades, except P. stricta, which was placed basal to all clade 8 species (Fig. 1). New subclades were assigned to clade 2 (Fig. 2), clade 6 (Fig. 3), clade 7 (Fig. 4) and clade 9 (Fig. 5).

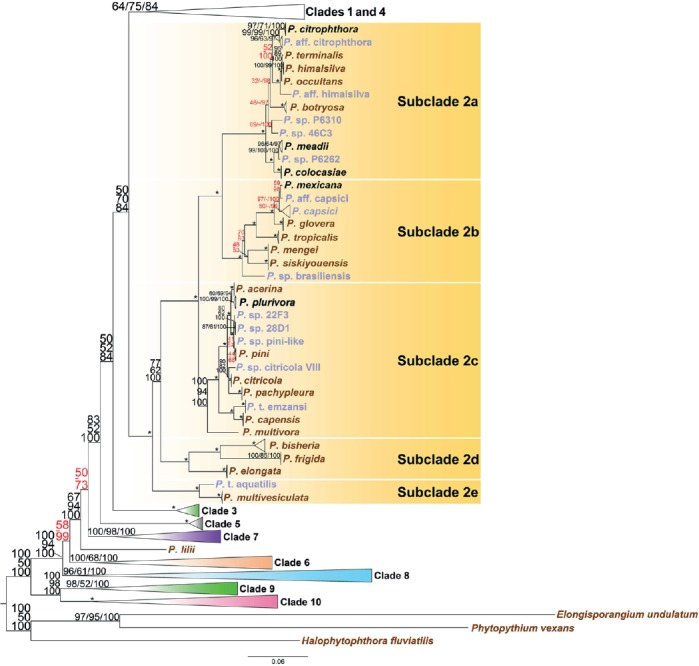

Fig. 2.

Structure of Phytophthora clade 2 in a genus-wide phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora based on concatenated sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers. Topology and branch lengths of maximum likelihood analysis are shown. Bootstrap values for maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (percentages) are indicated on individual nodes and separated by a forward slash. An asterisk is used in place of nodes with unambiguous (100 %) support in all three analyses. A dash is used in place of a topology from an analysis ambiguous to the other two analyses and these sets of numbers with ambiguity in one analysis are also highlighted in red. Species represented by ex-types and authentic isolates are written in brown and blue, respectively. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site.

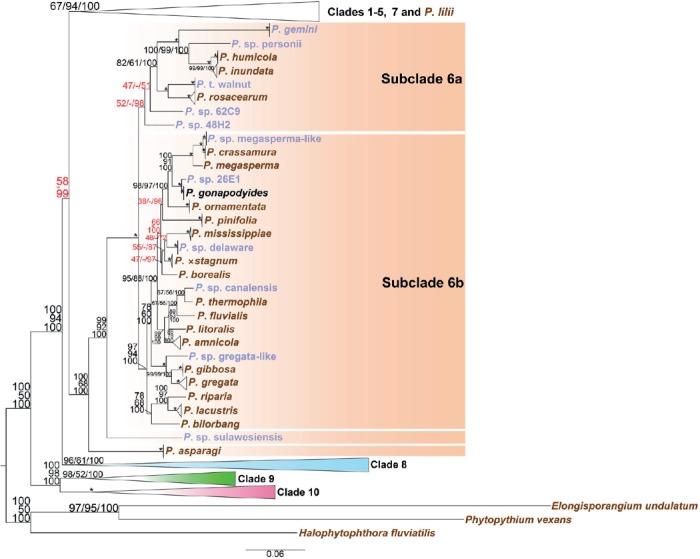

Fig. 3.

Structure of Phytophthora clade 6 in a genus-wide phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora based on concatenated sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers. Topology and branch lengths of maximum likelihood analysis are shown. Bootstrap values for maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (percentages) are indicated on individual nodes and separated by a forward slash. An asterisk is used in place of nodes with unambiguous (100 %) support in all three analyses. A dash is used in place of a topology from an analysis ambiguous to the other two analyses and these sets of numbers with ambiguity in one analysis are also highlighted in red. Species represented by ex-types and authentic isolates are written in brown and blue, respectively. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site.

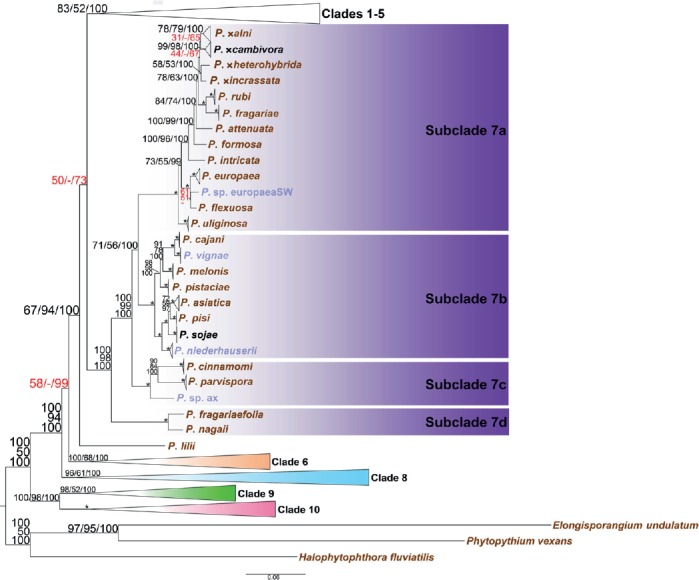

Fig. 4.

Structure of Phytophthora clade 7 in a genus-wide phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora based on concatenated sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers. Topology and branch lengths of maximum likelihood analysis are shown. Bootstrap values for maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (percentages) are indicated on individual nodes and separated by a forward slash. An asterisk is used in place of nodes with unambiguous (100 %) support in all three analyses. A dash is used in place of a topology from an analysis ambiguous to the other two analyses and these sets of numbers with ambiguity in one analysis are also highlighted in red. Species represented by ex-types and authentic isolates are written in brown and blue, respectively. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site.

Fig. 5.

Structure of Phytophthora clade 9 in a genus-wide phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora based on concatenated sequences of seven nuclear genetic markers. Topology and branch lengths of maximum likelihood analysis are shown. Bootstrap values for maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (percentages) are indicated on individual nodes and separated by a forward slash. An asterisk is used in place of nodes with unambiguous (100 %) support in all three analyses. A dash is used in place of a topology from an analysis ambiguous to the other two analyses and these sets of numbers with ambiguity in one analysis are also highlighted in red. Species represented by ex-types and authentic isolates are written in brown and blue, respectively. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site.

Several species were placed basal to other species in their respective clades. First, the cluster of P. quercina and P. sp. ohioensis was placed basal to other species of clade 4 in all three analyses. The bootstrap supports of the ML and MP analyses, and PP (percentage) for the separation of this cluster from that of P. alticola, P. arenaria, P. megakarya, P. palmivora, and P. quercetorum in clade 4 were only 48, 78, and 84, respectively (Fig. 1). Second, P. lilii was excluded from all known clades; it was placed basal to clades 1–5 and 7 (Fig. 1). Third, in clade 6, bootstrap support for the ML and MP analyses, and PP for all species except P. asparagi and P. sp. sulawesiensis were 100/100/100 (Fig. 3). This set of support numbers decreased to 99/92/100 when P. sp. sulawesiensis was included, and to 100/68/100 when further including P. asparagi (Fig. 3). Fourth, the support numbers for clade 8 species excluding P. stricta was 100/100/100, but 96/61/100 when P. stricta was included (Fig. 1). Fifth, all papillate species in clade 10 (Table 1) formed a well-supported main cluster, while two more recently described non-papillate species, P. gallica and P. intercalaris, were placed basal to the main cluster (Fig. 1).

New subclades in clades 2, 6, 7, and 9

(a) Clade 2

In addition to the previously recognized subclades 2a and 2b, many species, such as P. acerina, P. capensis, P. citricola, P. multivora, P. pachypleura, P. plurivora, and P. pini in the commonly referred to “Phytophthora citricola-complex” defined a new subclade 2c (Fig. 2). Furthermore, P. bisheria, P. frigida, and P. elongata formed new subclade 2d and the cluster of P. multivesiculata and P. taxon aquatilis formed new subclade 2e, with maximum support values in each case (Fig. 2).

(b) Clade 6

Subclade 6a included P. gemini, P. humicola, P. inundata, P. rosacearum, P. sp. personii, P. sp. 48H2, P. sp. 62C9 and P. taxon walnut. The cluster of P. rosacearum and P. taxon walnut could not be separated from that represented by P. gemini with only moderate support values for separation (82/61/100) (Fig. 3). Isolates 62C9 and 48H2, belonging to two new species, had ambiguous placements within subclade 6a among the three analyses (Fig. 3). With approximately 20 species newly included in the present phylogeny, the previously recognized “P. megasperma-P. gonapodyides complex” (Brasier et al. 2003a), subclade II of clade 6 (Jung et al. 2011), or subclade 6b (Kroon et al. 2012) expanded and its separation from subclade 6a was well-supported by 100/100/100 values (Fig. 3). Within subclade 6b, separation of the cluster of P. bilorbang, P. lacustris, and P. riparia from the other subclade 6b species was highly supported by 97/94/100 (Fig. 3), indicating that these three species may define a new subclade, although this is not done in this study. Phytophthora sp. sulawesiensis was placed basal to other clade 6 species except for P. asparagi, while P. asparagi was basal to all other species in clade 6 (Fig. 3). Phytophthora asparagi was previously assigned as subclade 6c (Kroon et al. 2012) and subclade III of clade 6 (Jung et al. 2011); considering that the support value of MP analysis was only moderate (68 %) when this single taxon was included (Fig. 3), this previous assignation as a subclade was not adopted here. In addition, in order to be consistent with subclade names in other clades, subclades 6a and 6b were used here instead of subclades I and II by Jung et al. (2011).

(c) Clade 7

Four subclades were distinguished in clade 7. Separation of the previously assigned subclades 7a and 7b was only moderately supported by values 71/56/100 (Fig. 4). The general structure of subclade 7a remained the same even with the addition of seven new taxa. Six of these new species, including P. attenuata, P. flexuosa, P. formosa, P. intricata, P. ×heterohybrida, and P. ×incrassata were recently recovered from forest soils and streamwater in Taiwan (Jung et al. 2017). On the other hand, P. cinnamomi and P. parvispora were separated from subclade 7b. They, along with a provisional species, P. sp. ax from Virginia, USA (Table 1), formed a distinct new subclade 7c (Fig. 4). The new subclade 7d, including two recently described species from Japan (Rahman et al. 2014b), P. fragariaefolia and P. nagaii, was placed basal to other subclades in clade 7 (Fig. 4).

(d) Clade 9

The split of clade 9 into two subclades 9a and 9b was highly supported in ML (98 %) and BA (100 %) analyses and moderately supported in the MP (52 %) analysis (Fig. 5). However, monophyly was highly supported for subclade 9b (100/100/100) but not for subclade 9a (44/-/95) (Fig. 5). Within subclade 9a, three monophyletic clusters were formed: 9a1, 9a2, and 9a3. However, support for the separation of these three clusters was moderate or ambiguous. In particular, the MP results did not produce any consistent separation of the three clusters (Fig. 5). Cluster 9a1 included many recently described high-temperature tolerant species, such as P. aquimorbida, P. chrysanthemi, P. hydropathica, P. macilentosa, P. parsiana, and P. virginiana). The cluster of P. macrochlamydospora (two lineages with two isolates in each lineage, Table 1) and P. quininea constituted 9a2 (Fig. 5). The cluster of two other high-temperature tolerant species P. insolita and P. polonica constituted 9a3 (Fig. 5). The well-supported cluster of P. captiosa, P. constricta, and P. fallax was assigned as subclade 9b (Fig. 5).

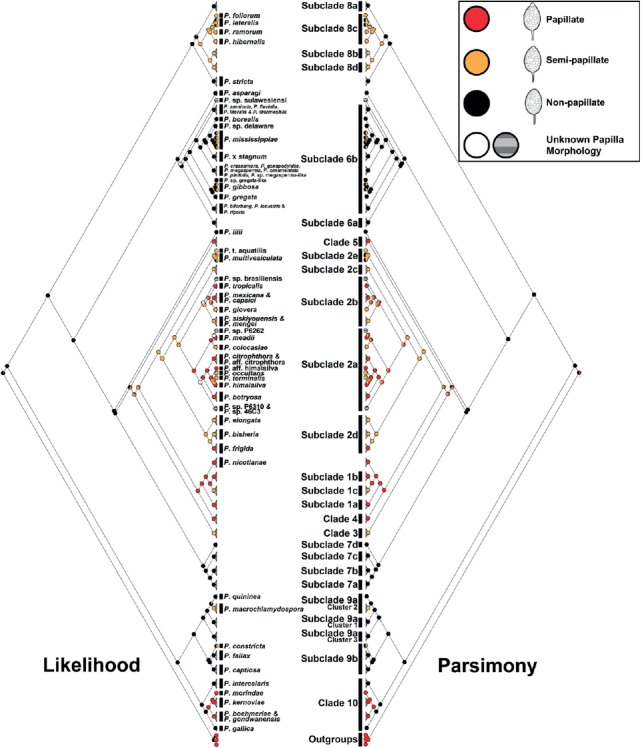

Evolutionary history of sporangial papillation inferred from ancestral character state reconstructions

Sporangial papillation of individual species is indicated in Table 1 and Fig. 6. Due to the size of the cladograms, clusters including species with the same sporangial papillation within each (sub)clade were compressed in Mesquite. Both likelihood and parsimony methods suggested that non-papillate is the progenitor state of Phytophthora species, and that semi-papillate and papillate types were derived from the non-papillate. The analyses indicated three major clusters of semi-papillate and (or) papillate species diverged from the non-papillate ancestors. First, species in clades 1 to 5 (semi-papillate or papillate) diverged from non-papillate species in clade 7 and P. lilii (Fig. 6). Second, species in subclades 8b to 8d (semi-papillate) diverged from non-papillate subclade 8a species (Fig. 6). Third, papillate clade 10 species including P. boehmeriae, P. gondwanensis, P. kernoviae, and P. morindae diverged from the non-papillate P. gallica and P. intercalaris (Fig. 6). Several species such as P. macrochlamydospora, P. mississippiae, P. gibbosa, and P. constricta also evolved to produce partially semi-papillate sporangia (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Ancestral state reconstructions of sporangial papillation for the genus Phytophthora based on likelihood (left cladogram) and parsimony (right cladogram). Trace character history analyses were performed on the maximum likelihood phylogeny in Mesquite. Clusters including species of uniform sporangial papillation within individual (sub)clades were compressed in Mesquite.

DISCUSSION

Here we presented an expanded phylogeny for the genus Phytophthora, encompassing 142 formally named and 43 provisionally recognized species (Table 2). In addition to this comprehensive coverage, this expanded phylogeny features over 1500 signature sequences generated from 278 ex-type and authentic isolates of 162 Phytophthora taxa (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, this study provided new insights into the evolutionary history of sporangial papillation in Phytophthora.

The expanded phylogeny provides a sound taxonomic framework for this agriculturally and ecologically important genus. One hundred and fourteen ex-types were included, representing 80 % of the 142 formally named species in this phylogeny. The majority of the 29 species not represented by ex-types, such as P. gonapodyides, P. infestans, P. meadii, P. mexicana, and P. nicotianae, were described long ago without designation of an ex-type culture. Likewise, almost all the 43 provisional species in this phylogeny were represented by authentic isolates from the originators of the respective species (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). This new framework will facilitate identification of new taxa in the future. As the genus continues to rapidly expand, some recently described species were not included in this study: P. mekongensis in subclade 2a (Puglisi et al. 2017), P. amaranthi in subclade 2b (Ann et al. 2016), P. boodjera in clade 4 (Simamora et al. 2015), P. chlamydospora in subclade 6b (Hansen et al. 2015), P. uniformis (basionym: P. alni subsp. uniformis) and P. ×multiformis (basionym: P. alni subsp. multiformis) in subclade 7a (Brasier et al. 2004, Husson et al. 2015), P. pseudolactucae in subclade 8b (Rahman et al. 2015), and P. prodigiosa (Puglisi et al. 2017) and P. pseudopolonica (Li et al. 2017) in subclade 9a. Likewise, some informally designated species also were not included: such as P. taxon humicola-like, P. taxon kwongan, and P. taxon rosacearum-like in subclade 6a (Jung et al. 2011). These and other emerging species are yet to be incorporated in the overall phylogeny of the genus.

The generation of over 1500 signature sequences from ex-types and authentic isolates in this study will aid researchers and first responders in correctly identifying Phytophthora cultures to the species level. DNA sequencing of selected genetic markers has become common practice in the identification of Phytophthora cultures (Kang et al. 2010). However, it is recognized that the accuracy of culture identity determined by this approach depends on the quality of the reference sequences used – and currently many sequence deposits are erroneously identified in public repositories, including GenBank (Kang et al. 2010). These errors originated in sequence deposits of cultures that were identified by morphological characters alone, and compounded by those identified through sequence matches to erroneous reference sequences or by single DNA markers (Kang et al. 2010). In this study, 29 isolates were found associated with an erroneous or modified identity (Supplementary Table 2). For instance, isolate 29B3 in clade 1 was identified as P. pseudotsugae and used as a key isolate for this species by Gallegly & Hong (2008). However, its sequences were distinct from those of the P. pseudotsugae ex-type (ATCC 52938). In the phylogenetic tree, it was basal to the cluster of P. cactorum and P. hedraiandra, thus its species identity was changed to P. aff. pseudotsugae (Fig. 1). In clade 2, isolate 26H4 was identified as P. citrophthora (Gallegly & Hong 2008) but sequences and phylogeny showed that it was close to but distinct from P. citrophthora isolates 03E5 and 26H3. It formed a cluster with isolate IMI 342898 (P10341), which was coded as P. sp. aff. colocasiae-1 by Martin et al. (2014). The identity of both isolates was then changed to P. aff. citrophthora (Fig. 2). Similarly, in clade 8, isolate 22G2 had been identified as P. cryptogea, although it was distinct from the P. cryptogea ex-type 61H9 (CBS 113.19). In the phylogenetic tree, it was basal to the cluster of P. cryptogea and P. erythroseptica, and the species identity was consequently changed to P. aff. cryptogea (Fig. 1). Changes in the identifications of these isolates, including the new and original names used, are indicated in Supplementary Table 2. The changes in the naming of these isolates highlights the importance of using signature sequences from ex-type or authentic isolates as references in future culture identification. In order to facilitate this practice, the signature sequences generated from ex-types or authentic isolates in the present study are marked as ‘(ex-type)’ or ‘(authentic)’, respectively, under the ‘isolate’ section in the ‘feature’ table of GenBank deposits. The research, diagnostic and regulatory communities are encouraged to use these sequences as references in future culture identification.

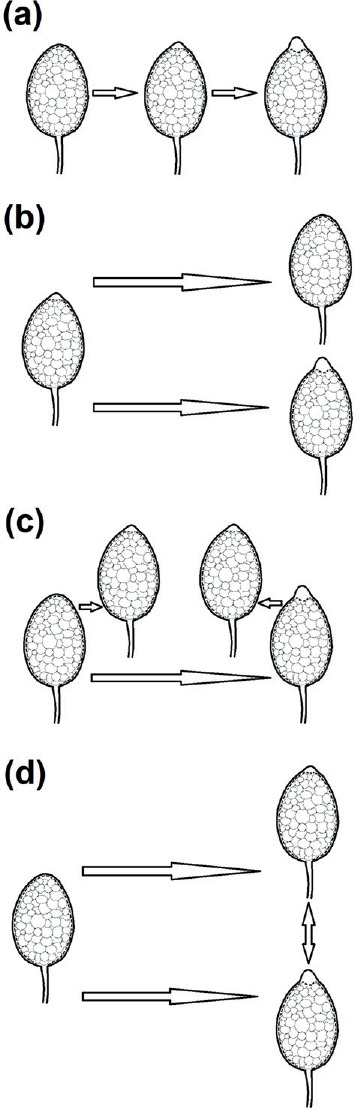

This study provided new insights into the evolutionary history of sporangial morphology in the genus Phytophthora, a subject that has fascinated generations of mycologists and plant pathologists. There have been three major hypotheses regarding the development of papillation, as illustrated in Fig. 7a, b, and c, respectively. First, papillate species were considered as descendants of Pythium-like, non-papillate ancestors and semi-papillation has been considered as intermediate between non-papillation and papillation (Blackwell 1949, Cooke et al. 2000, Erwin & Ribeiro 1996). Second, some semi-papillate species, exemplified by P. primulae in the group III of Waterhouse (1963) are primitive; they were suggested to have evolved to papillate and non-papillate species through two distinct evolutionary lines (Brasier 1983). Third, semi-papillate sporangia are morphological variants of papillate and non-papillate types (Cooke et al. 2000). Here we suggest that the non-papillate type is ancestral, and that non-papillate species could have evolved directly into either semi-papillate or papillate species (Fig. 7d). The evolution to semi-papillate species is exemplified by those in subclades 8b–d (Fig. 1), while evolution to papillate species is illustrated by P. boehmeriae and other papillate species in clade 10 (Fig. 1).The relationship between semi-papillate and papillate species appears to be more complicated (Fig. 7d). We also hypothesize that some semi-papillate species, such as those in subclade 1c, may have diverged from papillate ancestors, while some papillate species such as P. frigida may have evolved from semi-papillate ancestors of subclade 2d (Fig. 6).

Fig. 7.

Illustration of hypotheses on evolution of Phytophthora and associated changes in sporangial papillation: (a) species producing papillate sporangia evolved from non-papillate ancestors. Semi-papillation is considered as intermediate between non-papillation and papillation (Blackwell 1949, Cooke et al. 2000, Erwin & Ribeiro 1996); (b) some semi-papillate species, exemplified by P. primulae in the group III of Waterhouse (1963), are primitive and evolved to be non-papillate and papillate through two evolutionary paths, by Brasier (1983); (c) papillate species evolved from non-papillate ancestors. Semi-papillate species have been considered as morphological variants of papillate or non-papillate species, by Cooke et al. (2000); (d) a new hypothesis developed in this study that non-papillate ancestors evolved directly to either papillate or semi-papillate species. Some semi-papillate species further evolved to be papillate, or vice versa.

These new hypotheses are supported by the results from phylogeny and ancestral state reconstructions that suggest three major evolutionary paths in sporangial papillation of Phytophthora species (Fig. 1). First, the ancestor of modern species in clades 1–5 evolved to be papillate or semi-papillate (Figs 1, 6) while diverging from the common non-papillate ancestor of clade 7 species (Figs 1, 6). Second, the common ancestor of species in subclades 8b–d diverged from that of subclade 8a species while acquiring semi-papillation (Figs 1, 6). Third, the common ancestor of five clade 10 species in the main cluster including P. boehmeriae, P. gondwanensis, P. kernoviae, P. morindae, and P. sp. boehmeriae-like, acquired papillate sporangia while diverging from two non-papillate clade 10 species, P. gallica and P. intercalaris (Figs 1, 6). Besides these three major groups of papillate or semi-papillate species, a few species may have evolved to acquire semi-papillation independently, such as P. macrochlamydospora in clade 9 (Fig. 6). This evolutionary process may be underway for some other species including P. constricta, P. gibbosa, and P. mississippiae, which all produce both semi-papillate and non-papillate sporangia (Fig. 6). Furthermore, evolutionary reversion to partial production of non-papillate sporangia may have occurred in P. multivesiculata and P. lateralis in two semi-papillate subclades 2e and 8c, respectively (Fig. 6). However, that conclusion is uncertain due to limited and ambiguous data from species in these two subclades. Specifically, P. lateralis was ambiguously reported as non-papillate (Erwin & Ribeiro 1996, Gallegly & Hong 2008, Martin et al. 2012, Tucker & Milbrath 1942) or non- to semi-papillate (Kroon et al. 2012) in different studies. In subclade 2e, the only sister taxon of P. multivesiculata, P. taxon aquatilis, was provisionally described as semi-papillate, but only based on a single isolate (Hong et al. 2012). Evolutionary reversion in the sporangial papillation of these two species requires validation in the future. Also, more studies are warranted to analyze additional characters based on phylogenies with better clade-to-clade resolutions and provide a more comprehensive picture on the evolutionary history of Phytophthora species.

That a number of species were placed basal to other species in their respective clades in this expanded phylogeny presents a significant challenge to the monophyly of their respective clades and the current 10-clade system. First, P. stricta was initially placed close to other species in subclade 8a based on sequences of the cytochrome c oxidase 1 (cox1) gene, but was not grouped in any ITS clade (Yang et al. 2014a). This species was grouped in clade 8 in our expanded phylogeny by ML and BA analyses (Fig. 1); the monophyly of this clade was only moderately supported (61 %) in the MP analysis (Fig. 1). Second, the monophyly of clade 6 including P. asparagi was only moderately supported (68 %) in the MP analysis (Fig. 3). Third, although the inclusion of P. intercalaris in clade 10 was supported with maximum values, the exact positions of this species and P. gallica were still unresolved since the next node was only moderately supported (53 %) in the ML analysis and ambiguous in the MP analysis (Fig. 1). Fourth, similar to the finding of Blair et al. (2008), support for the monophyly of clade 4 including P. quercina and P. sp. ohioensis was only moderate (48/78/84). Also, similar ambiguity in the placement of the ‘P. quercina – P. sp. ohioensis’ cluster was observed among different phylogenetic approaches, and using different datasets including nuclear, mitochondrial, and combined nuclear and mitochondrial sequences (Martin et al. 2014). Fifth, this phylogeny confirmed the finding by Rahman et al. (2015) that P. lilii was not grouped in any clade of the current 10-clade system (Fig. 1). This species was not assigned as a distinct clade in our study, due to the relatively low clade-to-clade resolutions (Fig. 1). Further analyses are warranted to determine whether this unique species should be assigned as a new clade.

Although many branches in the expanded phylogeny have consistent maximum support in all three methods, some have only moderate to low or inconsistent support. These results highlight the challenges of correctly inferring the evolutionary separation of many closely related Phytophthora species, even when concatenated sequences from seven phylogenetic markers were used. It can be expected that as the cost of gene sequencing drops further, it will become possible to increase phylogenetic resolution among Phytophthora species by using concatenations of much larger numbers of genes. For example, Ye et al. (2016) used 293 concatenated housekeeping proteins to infer a robust phylogeny of seven fully sequenced Phytophthora species and confirmed that downy mildews (represented by three genome sequences) are nested within the genus Phytophthora, close to Phytophthora clade 4 (Ye et al. 2016). However, even with full genome sequences, ambiguity may not be completely resolved in cases where speciation has involved large populations of sexually reproducing individuals, for example, as a result of geographic separation. In these cases, there may be many sequence polymorphisms shared among separated species and these may confound the inference of a reliable phylogeny. Resolution of this level of ambiguity may require sequencing the whole genome of many isolates from the species of interest as well as using improved phylogenetic and coalescent methods.