Abstract

Introduction

The introduction of the faecal calprotectin (FC) test to screen children with chronic gastrointestinal complaints has helped the clinician to decide whether or not to subject the patient to endoscopy. In spite of this, a considerable number of patients without inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is still scoped. Faecal calgranulin C (S100A12) is a marker of intestinal inflammation that is potentially more specific for IBD than FC, as it is exclusively released by activated granulocytes.

Objective

To determine whether the specificity of S100A12 is superior to the specificity of FC without sacrificing sensitivity in patients with suspected IBD.

Methods

An international prospective cohort of children with suspected IBD will be screened with the existing FC stool test and the new S100A12 stool test. The reference standard (endoscopy with biopsies) will be applied to patients at high risk of IBD, while a secondary reference (clinical follow-up) will be applied to those at low risk of IBD. The differences in specificity and sensitivity between the two markers will be calculated.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is submitted to and approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands) and the Antwerp University Hospital (Belgium). The results will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication, conference presentation and incorporation in the upcoming National Guideline on Diagnosis and Therapy of IBD in Children.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02197780.

Keywords: S100A12 protein; S100 proteins, inflammatory bowel disease, screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective multicentre study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of a new faecal marker (S100A12) with respect to the currently used faecal marker (calprotectin) to select children with gastrointestinal complaints for endoscopy.

Our study design reflects current clinical practice in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Due to the invasive nature of the preferred reference standard (endoscopy) we used clinical follow-up as alternative reference test.

A limitation of the use of two reference standards is the introduction of a differential verification bias.

We present a Bayesian approach to deal with the introduced differential verification bias.

Introduction

Background and rationale

The introduction of the calprotectin stool test to screen children with chronic gastrointestinal complaints has helped the clinician to decide whether or not to refer the patient for endoscopy.1–4 We have shown that children with normal screening test results (≤50 µg/g) have a low probability of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and should therefore not undergo the invasive reference test (endoscopy) to exclude IBD.5 Children with elevated calprotectin levels, however, have a high probability of IBD and require referral to an endoscopy unit for endoscopic evaluation of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract.1 4 5 Although use of the calprotectin stool test rarely misses a child with IBD, the number of false positive cases who are scoped is considerable.1 5 Calprotectin is a member of the S100 calcium-binding protein family and is a heterodimer of S100A8 and S100A9. The protein is released mainly by neutrophil granulocytes, and also by other activated and damaged cells including monocytes, macrophages and epithelial cells.6 7 Calgranulin C (S100A12) is a less investigated member of the S100 protein family.7 8 Since S100A12 is only released by activated granulocytes, it is suggested to be more specific for gastrointestinal inflammation caused by IBD than calprotectin.7 9–11

Objectives

We hypothesise that a referral strategy based on faecal S100A12 will reduce the number of children wrongly selected for endoscopy as compared with a calprotectin-based strategy. The primary objective is to determine whether the specificity of S100A12 is superior to the specificity of calprotectin without sacrificing sensitivity. The secondary objective is to calculate the diagnostic accuracy characteristics and best cut-offs for both S100A12 and calprotectin.

Methods

Design

The CACATU (Calprotectin or Calgranulin C test before undergoing endoscopy) study is a prospective, observational, multicentre, diagnostic accuracy study with a paired design. A cohort of children with suspected IBD is screened with the calprotectin stool test (existing test) and with the S100A12 stool test (new test). Confirmation of the target condition (IBD) is based on endoscopy with biopsies (reference standard) or clinical follow-up (secondary reference standard).

Study setting

Study participants will be recruited from 15 general teaching hospitals and one academic centre in the Netherlands and from one general hospital and two academic centres in Flanders, Belgium. The names of all participating centres can be found in the trial registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov). The principal investigators at the various sites are general paediatricians or paediatric gastroenterologists. Six participating centres (three academic and three general hospitals) have a paediatric endoscopy unit.

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible if they were between 6 and 17 years old and presented with at least one major criterion or two minor criteria suggestive of IBD (box 1).

Box 1. Study inclusion criteria (one major criterion or two minor criteria are required to make the patient eligible for participation in the CACATU study).

Major criteria

Persistent diarrhoea for more than 4 weeks

Recurrent abdominal pain with diarrhoea with at least two episodes in the previous 6 months

Rectal blood loss

Perianal disease (fistula, deep fissure, abscess)

Minor criteria

Involuntary weight loss

First-degree family member with inflammatory bowel disease

Anaemia (haemoglobin <2 SD for age and gender)

Increased marker of inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/hour or C reactive protein >10 mg/L)

Extraintestinal symptoms (erythema nodosum, arthritis, uveitis, thromboembolism, aphthous ulcers)

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the difference in specificity between faecal calprotectin (FC) and S100A12. Secondary endpoints are the difference in sensitivity and the diagnostic accuracy characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, area under the curve, best cut-off point) for both markers individually. All diagnostic accuracy characteristics will be calculated with predefined cut-off points that have been documented in the medical literature, and with best cut-off points based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Intervention

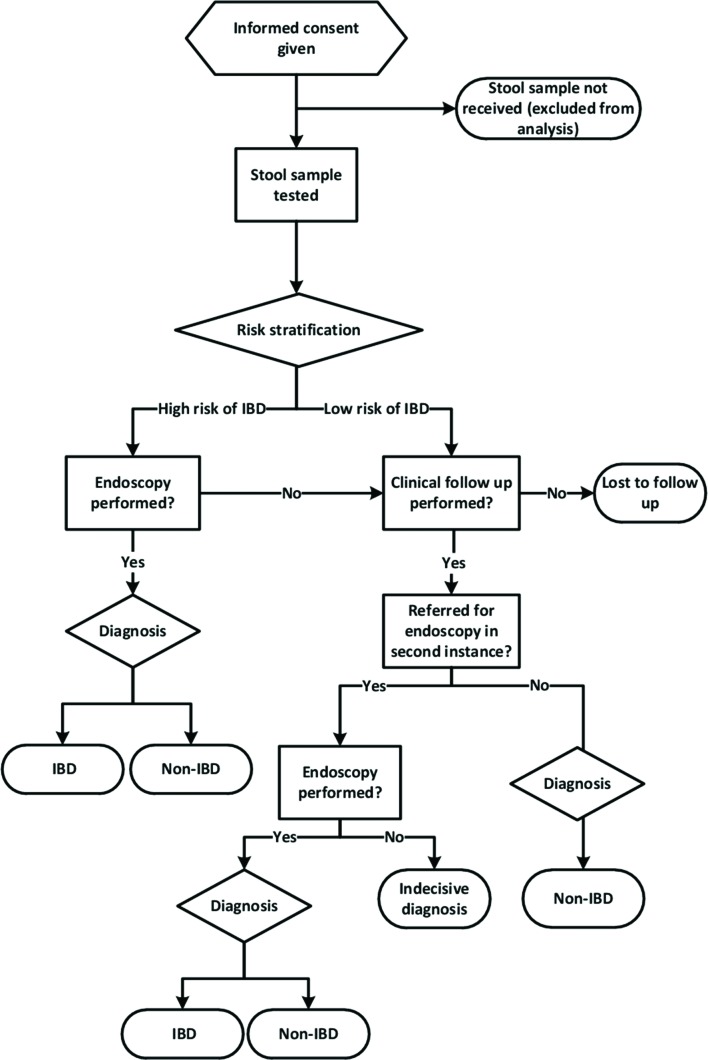

Patients who fulfil the inclusion criteria will be risk stratified (high vs low risk of IBD) according to presenting symptoms, blood tests and stool calprotectin (figure 1). In general, we expect that those participants with increased calprotectin levels (> 50 µg/g) without colon pathogens are likely to be referred to endoscopy (the preferred reference standard) to confirm or exclude IBD. Patients with a normal stool calprotectin test level are likely to have a low probability of IBD and will be followed clinically to determine the final diagnosis (the alternative reference standard), unless there will be other indications to scope them. Paediatricians will be free to use any diagnostic test, such as coeliac disease screening, breath test or ultrasonography (whichever is deemed suitable).

Figure 1.

CACATU study flow. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Participant study flow

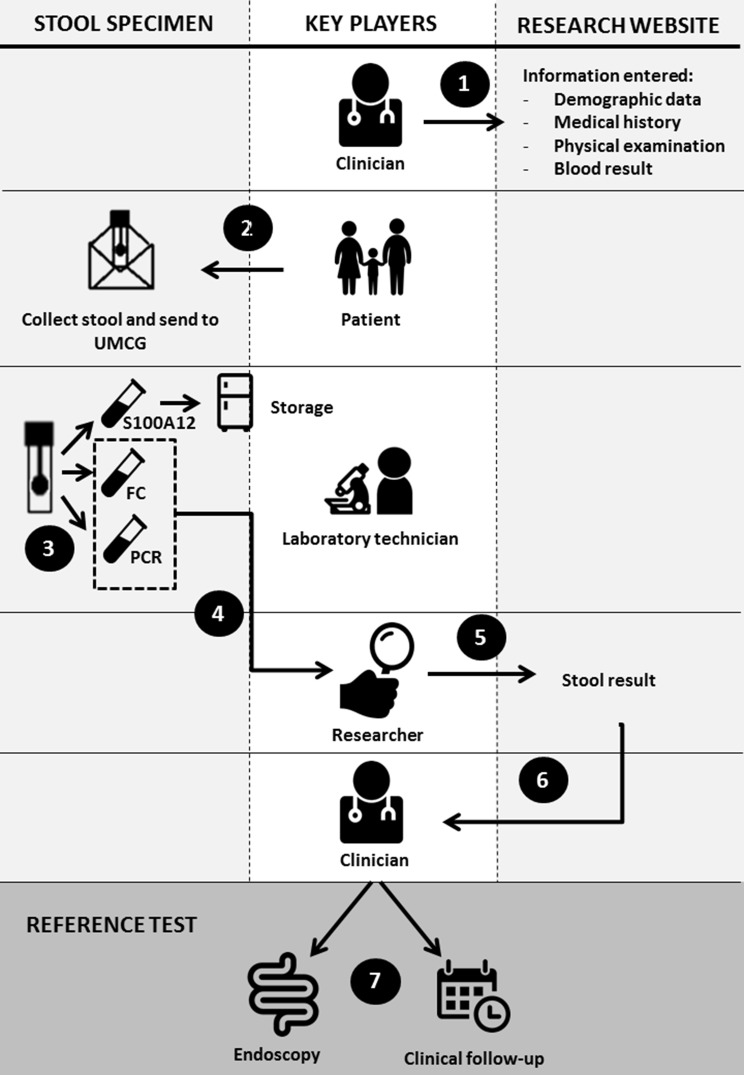

Eligible participants will be invited for participation by the attending paediatrician. Baseline characteristics, date of birth, major and minor criteria (box 1), use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and blood tests (haemoglobin, C reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum alanine transaminase and gamma-glutamyltransferase) will be entered on a study website (figure 2, step 1). Participants will be asked to defecate onto a stool collection sheet held above the toilet water and collect one sample with a screw-top container with spoon (step 2). The stool sample is sent to the Department of Laboratory Medicine of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) in a biomaterial envelope. Immediately after arrival, the stool calprotectin level will be measured. The residue will be split with one-half stored at −80°C for S100A12 batch testing at a later stage, and the other half will be used to determine enteric pathogens with a PCR technique (step 3). The PCR analysis will include Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, E. coli O157gen, Cryptosporidium, Dientamoeba fragilis, Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Salmonella, Shigella/Enteroinvasive E. coli and Campylobacter. Results of calprotectin test and PCR analysis will be uploaded to the website, and will then be made visible to the local clinician (steps 4 and 5). The paediatrician will receive an email notification with an automated advice on the next best move (step 6). However, the choice of the reference standard (endoscopy or clinical follow-up) is up to the paediatrician’s discretion (step 7).

Figure 2.

CACATU study flow from first hospital visit to choice of reference test. Step 1: The clinician registers the patient on the study website (www.cacatustudie.eu). Step 2: The patient (or parent) collects the stool specimen and sends it to the hospital laboratory. Step 3: The lab divides the specimen into three portions: calprotectin and PCR are immediately performed; one tube is stored at −80°C for calgranulin C testing. Step 4: The lab sends the results of calprotectin and PCR to the researcher. Step 5: The researcher enters the test results on the website. Step 6: The clinician receives a notification with the results and an automated advice on the next best move. Step 7: Paediatrician decides the next best move: in case of high probability of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): endoscopy; in case of low probability of IBD: clinical follow-up. The ultimate decision to scope is in the hands of the endoscopist. FC, faecal calprotectin; UMCG, University Medical Center Groningen.

Timeline

The process from faeces collection to completion of the non-invasive diagnostic work-up is supposed to last no longer than 2 weeks. We will exclude samples with a transport time that exceeds 7 days and we will perform a subanalysis with those samples that are received within 4 days. In case of low risk of relapse, the treating paediatricians will receive a reminder for clinical follow-up 6 months after inclusion. The total running time of the study is 30 months, including 6 months to complete the follow-up.

Sample size

The primary outcome of interest is the difference in specificity between the new test (S100A12) and the established test (FC). If the specificity of S100A12 is superior to the specificity of FC without sacrificing sensitivity, we can replace the old test by the new test. McNemar’s test for paired data will be applied to compare specificities between both tests using a 2×2 table exclusively among non-IBD patients (table 1). Study participants with concordant results ((+, +) or (−, −)) do not distinguish between the two tests. The only information for comparing the sensitivities and specificities comes from those patients with discordant results ((+, −) or (−, +)). Sample size calculation is based on recommendations in Hayen et al.12 Weighed means of specificity of calprotectin were based on a recently published individual patient data meta-analysis.4 We assumed that faecal S100A12 would lead to a 50% relative improvement of specificity (from 70% to 85%). The prevalence of IBD and non-IBD in the CACATU study cohort is expected to be similar to the prevalence that we found earlier,1 as the study participants will come from the same region and comparable eligibility criteria will apply. The sample size calculation was done with Power Analysis and Sample Size software (version 11 for Windows). A sample size of 130 subjects with non-IBD achieves 80% power to detect a difference of 0.15 between the two diagnostic tests whose specificities are 0.70 and 0.85. This procedure used a two-sided McNemar test with a significance level of 0.05. The prevalence of non-IBD in the population is 0.64, and the proportion of discordant pairs is 0.23. We aim to include at least 250 participants in order to correct for participants diagnosed with IBD (estimated 36%) and participants that will be lost to follow-up (estimated 25%).

Table 1.

Data table of principle of paired design for the faecal markers calprotectin and calgranulin C

| Faecal calgranulin C | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Total | ||

| Diagnosis: no IBD | ||||

| Faecal calprotectin | Positive | Concordant (v) | Discordant (w) | v+w |

| Negative | Discordant (x) | Concordant (y) | x+y | |

| Total | v+x | w+y | N− | |

| Diagnosis: IBD | ||||

| Faecal calprotectin | Positive | Concordant (r) | Discordant (s) | r+s |

| Negative | Discordant (t) | Concordant (u) | t+u | |

| Total | r+t | s+u | N+ | |

Null hypothesis H0 (specificity): w=x; alternative hypothesis H1: w≠x.

Null hypothesis H0 (sensitivity): s=t; alternative hypothesis H1: s≠t.

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Recruitment

We asked all participating centres to predict how many eligible patients they could recruit during the enrolment period. Their estimates were based on the list of diagnoses of the previous year, and their estimated totals convinced us that reaching the target sample size is realistic. Retention will be promoted by sending automated reminders to the treating physician to complete the blanks in blood tests, and to reassess patients with initial low probability of IBD after 6 months.

Test methods

Index tests

Faecal calprotectin

FC levels will be measured with the fCal ELISA test of BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG (Schönenbuch, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A level of 50 µg/g is the predefined cut-off value.2 4 5 13

Faecal calgranulin C (S100A12)

S100A12 levels will be measured by one experienced laboratory technician. The maximal duration of storage of the stool sample in our −80°C freezer is 6 months. Analyses will be performed with a sandwich ELISA, trademark Inflamark (CisBio Bioassays, Codolet, France) on a Dynex DS2 Automated ELISA System (Alpha Labs, Easleigh, UK), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. In summary, after extraction step, 100 µL of prediluted samples will be transferred in duplicate into the corresponding wells coated with anti-S100A12 monoclonal antibody. Incubation time is 30 min, followed by three washing cycles with Tween 20. The next step is adding 100 µL of the second monoclonal antibody, anti S100A12 coupled to horseradish peroxidase followed by a second incubation period of 30 min and three washing cycles. Next, 100 µL of the substrate, tetramethylbenzidine, is pipetted in all wells. The wells are protected from light and after 10 min, the sulfuric acid stop solution is added. The absorbance will be read at 450 nm. For each duplicate, the mean optical density will be calculated and a calibration curve will be constructed. The curve will be plotted as a cubic regression with DS-matrix software, version 1.23 (Dynex technologies, Chantilly, USA). Purified human S100A12 will be used as calibrator (included in the kit).

The predefined cut-off value of S100A12 is 0.75 mg/kg, which is based on a reference value study among 120 healthy school-aged children and adolescents.14

Reference tests

Endoscopy

Endoscopy will be the reference standard for patients at high risk of IBD. This procedure will be performed under anaesthesia by an experienced paediatric gastroenterologist. Ideally, both upper and lower gastrointestinal tract will be evaluated according to the revised Porto criteria,15 and biopsies will be taken from every bowel segment. Histopathological examination will be performed by experienced histopathologists. Endoscopists and histopathologists will have access to clinical information and FC test results, but will be blinded to the results of the S100A12 test.

Clinical follow-up

This secondary reference will be applied to patients at low risk of IBD. Six months after study inclusion, the treating paediatrician will receive a notification to enter a second evaluation of major and minor criteria (box 1). Blood tests will only be repeated when deemed necessary by the treating paediatrician. In addition, a second faeces sample will be collected and sent in for analysis. Patients who remain suspected of having IBD will be referred for further investigations in second instance. At study closure, one of the researchers (AH) will visit the participating centres to cross-check patient records for the definite diagnosis.

Rationale for choosing reference standard

Diagnostic endoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract (including intubation of the terminal ileum) in combination with biopsies is the recommended test to diagnose IBD.15 In children at high risk of IBD with negative endoscopy, small bowel imaging is encouraged.15 All of these procedures are invasive and require bowel preparation. Endoscopy is mostly performed with the patient under general anaesthesia. Although complications are rare, endoscopy is a burdensome procedure for a child. We found it unethical to expose children at low risk of IBD to endoscopy. Therefore, we decided to perform a secondary reference standard (clinical follow-up) in patients at low risk for IBD and to adjust for its imperfection.16

Blinding

Laboratory personnel will be blinded to the patient’s history, and to the results of endoscopy and biopsy. Although calprotectin testing is done within 24 hours after arrival of the faeces specimen and the residue is stored at −80°C for S100A12 batch testing at a later stage, sample labelling could theoretically link both faecal tests to one patient. Endoscopists and histopathologists will have access to clinical information and calprotectin test results, but will be blinded to the results of the S100A12 test.

Confidentiality and data management

Consecutive patients participating in the study will receive a unique study number. All demographic and medical data will be entered electronically on the study website by the local investigator and stored linked to this study number. Study investigators will receive access to a secured study website. Local investigators are able to consult only data from participants from their own centre. Faeces samples will be marked with a study number label and sent to the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the UMCG. Results of calprotectin test and PCR for enteric pathogens will be uploaded to the website by the coordinating investigator and will be visible to the local clinician. At the end of the study, the data entered on the study website will be cross-checked with the information in the local Electronic Health Databases. Data will be stored during the study period and until 15 years thereafter. When patients and their parents give permission, residual faeces will be stored for a maximum period of 15 years for future diagnostic research. The researchers AH, EvdV and PvR will have access to the final trial dataset.

Statistical methods

Data analysis will be done with SPSS V.22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Diagnostic accuracy characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value) will be presented for both markers individually. We will primarily use prespecified cut-off points of FC and S100A12. In the second instance, we will use the best cut-off points based on the ROC curves for both FC and S100A12.

We will use a Bayesian correction method to adjust for differential verification bias in the two reference standards in relation to latent IBD.17 Based on clinical experience, we defined a prior distribution. We assume that our reference standard endoscopy has 95%–100% sensitivity and 95%–100% specificity to diagnose IBD, and that our secondary reference standard clinical follow-up will have a sensitivity of 80%–100% and a specificity of 60%–80%. Bayes factors will be calculated using JAGS (‘Just Another Gibbs Sampler’), a free program licensed under GNU General Public License.

Missing values

In case the index test and reference standard results are missing, the patient will be excluded from further analysis.

Ethical approval and dissemination policy

The study will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (59th version, October 2008). The Medical Ethics Review Committee (MEC) of the UMCG is of the opinion that this study does not require approval according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO). The MEC of the Antwerp University Hospital approved the protocol. The legal guardian(s) of all participants, as well as children aged 12 and above, will need to give informed consent for participation and for storage of material for future research.

In case of important protocol amendments, both the MEC and trial registry will be informed. The results of the trial will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication, conference presentation and incorporation in the upcoming National Guideline on Diagnosis and Therapy of IBD in Children.

Study status

The first trial participant was included in September 2014. It is anticipated that the trial will end in the spring of 2017.

Discussion

We aim to further improve the accuracy to distinguish patients with a high risk of IBD from those with a low risk of IBD with the ultimate goal to reduce the number of futile endoscopies. We will compare the established faecal marker FC with the relatively unknown faecal marker S100A12. The FC test has excellent sensitivity for IBD (0.92–0.98),2–4 18 but its specificity, with point estimates varying between 0.60 and 0.68,2–4 18 leaves a considerable proportion of non-IBD patients being exposed to an invasive procedure. Studies with faecal S100A12 showed diagnostic promise under ideal testing conditions in preselected groups of healthy children and children with IBD.9 11 19 We only know of one report that compared FC and S100A12 in children presenting with gastrointestinal complaints.11 The sensitivity and specificity of S100A12 for detection of IBD were both 97%, where FC had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 67%.11

Methodological biases

In this diagnostic accuracy study, the performance of both stool tests will be assessed by verifying the results against endoscopy. Due to the invasive nature of this diagnostic procedure, verification can be performed only in a subset of patients with a high risk of IBD. An alternative reference test (ie, clinical follow-up) will be used in the remainder of the patients. The drawback of this so-called differential verification design is that the second reference test is of lesser quality. Simply adding the results of these two types of reference tests will lead to biased estimates of the overall test accuracy.16 We plan to correct for this differential verification bias by using a Bayesian approach, as described by De Groot et al.17Second, this study is a real-life study, in which the decision to expose a child to endoscopy is based on the combination of presenting symptoms, physical examination and results of blood and stool tests, as is currently recommended by Dutch and international scientific societies. Blinding treating physicians for the FC results was therefore irrational and impractical. Knowledge of the FC level will influence the physicians’ decision to refer a patient for endoscopic evaluation, which gives rise to a work-up bias.20 Furthermore, endoscopists will not be blinded for the level of FC and therefore this may theoretically affect the endoscopists’ assessment of the endoscopy (diagnostic review bias).

Implications for practice

If S100A12 has a better specificity than FC without sacrificing sensitivity, than S100A12 will be the dominant test to select patients for endoscopy. Replacing FC by S100A12 may then reduce the number of non-IBD patients being subjected to endoscopy. This will be good news for patients (less invasive tests), clinicians (shorter waiting lists for endoscopy) and health insurance companies (reduction of healthcare costs).

bmjopen-2016-015636supp001.doc (123.5KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PvR conceived the study. AH, EVdV, AMK and PvR initiated the study design. PvR is the grant holder. All authors contributed to the refinement of the study protocol. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by CisBio Bioassays (Codolet, France), developer and producer of the Inflamark ELISA kit used to measure S100A12 in faeces.

Competing interests: This trial is supported by CisBio Bioassays, producer of the Inflamark ELISA kit. PvR and AH received financial support from BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG (Schönenbuch, Switzerland) for other ongoing trials.

Ethics approval: MEC University Medical Center Groningen and MEC Antwerp University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Van de Vijver E, Schreuder AB, Cnossen WR, et al. . Safely ruling out inflammatory bowel disease in children and teenagers without referral for endoscopy. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:1014–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Reitsma JB, et al. . Noninvasive tests for inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152126 10.1542/peds.2015-2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson P, Anderson NH, Wilson DC. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:637–45. 10.1038/ajg.2013.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degraeuwe PLJ, Beld MPA, Ashorn M, et al. . Faecal calprotectin in Suspected Paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;60:339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heida A, Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, et al. . Avoid Endoscopy in children with suspected inflammatory bowel disease who have normal calprotectin levels. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:47–9. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Røseth AG, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, et al. . Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992;27:793–8. 10.3109/00365529209011186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foell D, Wittkowski H, Roth J. Monitoring disease activity by stool analyses: from occult blood to molecular markers of intestinal inflammation and damage. Gut 2009;58:859–68. 10.1136/gut.2008.170019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Logt F, Day AS. S100A12: a noninvasive marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. J Dig Dis 2013;14:62–7. 10.1111/1751-2980.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong NS, Leach ST, Day AS. Fecal S100A12: a novel noninvasive marker in children with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:566–72. 10.1097/01.ibd.0000227626.72271.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser T, Langhorst J, Wittkowski H, et al. . Faecal S100A12 as a non-invasive marker distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2007;56:1706–13. 10.1136/gut.2006.113431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sidler MA, Leach ST, Day AS. Fecal S100A12 and fecal calprotectin as noninvasive markers for inflammatory bowel disease in children. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:359–66. 10.1002/ibd.20336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayen A, Macaskill P, Irwig L, et al. . Appropriate statistical methods are required to assess diagnostic tests for replacement, add-on, and triage. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:883–91. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kostakis ID, Cholidou KG, Vaiopoulos AG, et al. . Fecal calprotectin in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:309–19. 10.1007/s10620-012-2347-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heida A, Muller Kobold AC, Wagenmakers L, et al. . Reference values of fecal calgranulin C (S100A12) in school aged children and teenagers. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. . ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:795–806. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naaktgeboren CA, de Groot JA, Rutjes AW, et al. . Anticipating missing reference standard data when planning diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2016;352:i402 10.1136/bmj.i402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Groot JA, Dendukuri N, Janssen KJ, et al. . Adjusting for differential-verification bias in diagnostic-accuracy studies: a bayesian approach. Epidemiology 2011;22:234–41. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318207fc5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin JF, Chen JM, Zuo JH, et al. . Meta-analysis: fecal calprotectin for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1407–15. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day AS, Ehn M, Gearry RB, et al. . Fecal S100A12 in healthy infants and children. Dis Markers 2013;35:295–9. 10.1155/2013/873582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi BC. Sensitivity and specificity of a single diagnostic test in the presence of work-up bias. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:581–6. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90129-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015636supp001.doc (123.5KB, doc)