Abstract

This essay examines how civil rights and their implementation have affected and continue to affect the health of racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Civil rights are characterized as social determinants of health. A brief review of US history indicates that, particularly for Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians, the longstanding lack of civil rights is linked with persistent health inequities. Civil rights history since 1950 is explored in four domains—health care, education, employment, and housing. The first three domains show substantial benefits when civil rights are enforced. Discrimination and segregation in housing persist because anti-discrimination civil rights laws have not been well enforced. Enforcement is an essential component for the success of civil rights law. Civil rights and their enforcement may be considered a powerful arena for public health theorizing, research, policy, and action.

Highlights

-

•

Civil rights are characterized as social determinants of health.

-

•

Four domains in civil rights history since 1950 are explored in—health care, education, employment, and housing.

-

•

Health care, education, employment show substantial benefits when civil rights are enforced.

-

•

Housing shows an overall failure to enforce existing civil rights and persistent discrimination.

-

•

Civil rights and their enforcement may be considered a powerful arena for public health theorizing, research, policy, and action.

“…race is the child of racism, not the father”.

Individual and community health are affected by their social and physical environments and resources available or absent in those environments World Health Organization (2010). Here we provide: 1) a framework for understanding how civil rights laws and their implementation, including enforcement are components of the social environment; 2) a summary of the evolution of civil rights law in U.S. history; 3) evidence that civil rights laws enacted since 1950 on (a) health care, (b) education, (c) employment, and (d) housing have (or have not) had beneficial effects on the health or on other social determinants of health of racial and ethnic minority populations previously lacking those rights; and 4) evidence that civil rights is an arena for public health theorizing, research, collaboration, policy, and action.

Framework: civil rights as a social determinant of health

“‘Civil rights are such as belong to every citizen of the state or country, or, in a wider sense, to all its inhabitants, and are not connected with the organization or administration of government. They include the rights of property, marriage, protection by the laws, freedom of contract, trial by jury, etc”(Garner, 2004).

A central notion of civil rights is that, with rare exception such as persons convicted of felony, rights available to any adult citizen are available to all, and that these rights cannot be denied to any person because of race, ethnicity, sex, or other protected class.1 Some government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid are provided only to persons qualified by age, income, or medical condition; however, within eligible populations, denying these benefits because of a beneficiary’s race or sex violates civil rights. Civil rights laws generally protect citizens from discriminatory practices by governments and institutions, but in some instances also protect citizens from discriminatory practices by other citizens Chemerinsky (2006). Civil rights may be protected by state and federal constitutions, statutes, and regulations interpreted by court decisions.

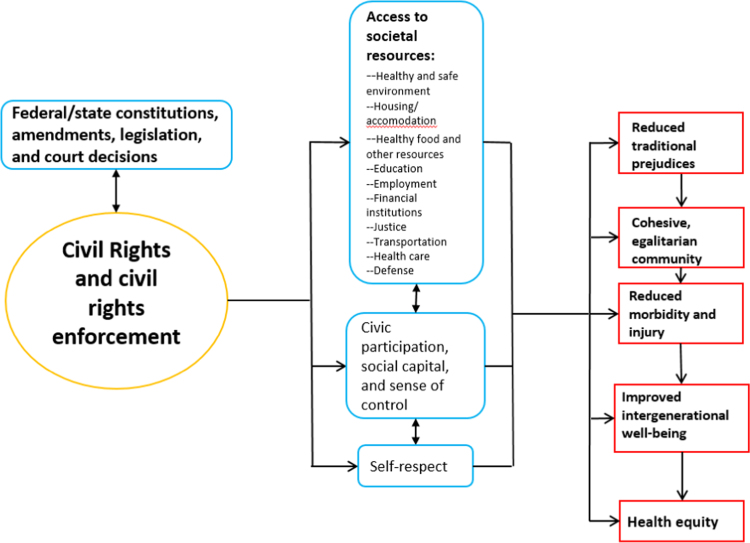

Civil rights laws and their enforcement are social determinants of health because they affect other social determinants of health, that is, elements of a society’s organization and process, such as education, housing, transportation, employment, and the system of justice, that causally affect the societal distribution of resources that in turn affect disease, injury, and health (Fig. 1). Social determinants, including civil rights laws and their enforcement, affect health by affecting intermediate factors such as housing, employment, and transportation which, in turn, affect the distribution of health risk and protective factors, such as pathogens and environmental toxins, and the resources for prevention and treatment (Hahn, 1995, Williams et al., 2008, Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014). As argued in the Brown v. Board of Education (“Brown”) decision, equitable access to societal resources assured by civil rights may also strengthen self-respect and a sense of control, sources of psychological health Clark (1971).

Fig. 1.

Effects of civil rights laws on public health and health equity.

Perhaps the civil rights domain with the most obvious health consequences is assured equal access to health care opportunities-- likely to have greatest effects on lower income families, including many racial and ethnic minority families (Williams et al., 2008; Smedley, Stith & Nelson, 2002). Equitable access to education is also essential for health equity, because it allows the development of basic knowledge, problem-solving abilities, and social-emotional skills (Hahn & Truman, 2015) that allow full participation in society (Hahn and Truman, 2015, Ross and Wu, 1995, Feinstein et al., 2006). Equitable access to employment, living wages, and fair opportunity for promotion also increase the likelihood of income which, in turn, can maintain or improve health by multiple means. The location and condition of housing affect occupants’ safety, distance from polluted environments, access to community resources, including transportation, food, recreation, employment, and financial institutions, as well as basic conditions of shelter (Galobardes et al., 2006a, Galobardes et al., 2006b). The quality of educational opportunity varies greatly by community income level, and residential location also powerfully affects access to educational resources and their long term health consequences Reardon and Owens (2014). Although we discuss civil rights by social domain, such as health care, education, employment, and housing, these rights are multiply interconnected Reskin (2012). Moreover, it is likely that all domains of civil rights are mutually reinforcing when in place, and mutually harmful when unenforced Reskin (2012).

A brief history of the pursuit of civil rights in the United States

In the United States, the principal roots of current and historical racial and ethnic health inequities are found in the societal distribution of resources and power that underlie long-term health. Individuals and groups with predominant power and resources divide the world into categories, such as “races”(Hill, 1996, Omi and Winant, 2014, Waldstreicher, 2010) and allocate power and resources to some groups while withholding power and resources from others, rationalized by questionable ideologies of merit, capacity, or other criteria.

From 1787–1791, the Founding Fathers rejected subjugation to British rule and established the United States government based on democratic principles. They institutionalized a Constitution and legislation that granted civil rights to people like themselves but not to others, including non-White populations and women of any race Zinn (2014). They allowed (Article I, Section 9) the importation of slaves until 1808. While some Founding Fathers held more egalitarian beliefs, the documents that framed the establishment of the nation, e.g., the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, were compromises that excluded slaves and American Indians from all rights. White Europeans occupied land inhabited by indigenous populations—“American Indians” and profited by the enslavement of Black populations from Africa Williams (2014). These racial and ethnic minority populations were excluded from civic participation and restricted in immigration and mobility, income and employment, marriage, and more, with substantial health consequences Steckel (1986). Such legal and civic restrictions on the Black slave population continued until forcefully interrupted by the Civil War of 1861–1865. Since then, efforts have increasingly been made (and resisted) to reverse multiple forms of unequal treatment through the enactment and enforcement of civil rights laws.

Several U.S. Supreme Court decisions and other legal milestones in civil rights history are basic to our thesis that the public health benefits of the implementation of civil rights laws can be large and long term (Table 1). In 1857, in the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, the Supreme Court affirmed that civil rights enumerated in the Constitution did not apply to free or enslaved Black Americans because they were not citizens when the Constitution was written. In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment made slavery unlawful and gave Congress enforcement powers.

Table 1.

Major laws and court decisions related to civil rights, United States 1791 to 2015.

| Legal Source (year enacted) | Judicial decision (J) or Legislation (L) | Populations covered | Major outcomesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bill of Rights (1791) | L | U.S. residents | Protection of individual rights and limitations on governmental powers |

| Dred Scott (1857) | J | Free and enslaved black people living in the USA | All black persons (negroes), free or enslaved, with African ancestry, are ineligible for US citizenship |

| 13th Constitutional Amendment (1865) | L | slaves | Slaves emancipated |

| An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication (1866) | L | U.S. residents | All resident populations guaranteed equal protection under law. |

| 14th Constitutional Amendment (1868) | L | all U.S. residents | All resident populations guaranteed equal protection under law. |

| 15th Constitutional Amendment (1870) | L | Black men | Freed Black slave men given right to vote |

| Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) | J | all U.S. residents | Separate but equal access to public facilities ruled legitimate |

| 19th Constitutional Amendment (1920) | L | U.S. women residents | Women given right to vote |

| Indian Citizenship Act (1924) | L | American Indians | American Indians given citizenship |

| Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) | J | housing covenants | Enforcement of exclusive housing covenants ruled unconstitutional |

| Brown v. Board of Education (1954) | J | all U.S. residents | Separate but equal ruled illegitimate |

| Simpkins v.Moses H.Cone Memorial Hospital (1963) | J | hospitals | Hospitals receiving federal funds were no longer considered private, but as arms of the state subject to federal requirements. |

| Civil Rights Act 1964 | L | all U.S. residents | |

| Key Titles | |||

| Title I | L | Bars unequal voter registration requirements | |

| Title II | L | Bars discrimination in public facilities engaged in interstate commerce | |

| Title III | L | Bars government discrimination in access to public facilities | |

| Title IV | L | Encourages desegregation of schools and advocates enforcement | |

| Title VI | L | Bars discrimination by government agencies that receive federal funds. | |

| Title VII, amended as Equal Employment Opportunity Act (1972) | L | Prohibits discrimination by covered employers | |

| Title VIII, amended as Fair Housing Act | L | Requires voting data in specified regions. Prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of homes | |

| Title IX | L | Facilitates transfer of civil rights cases from prejudicial state courts to federal court, fostering more consistent application of laws. | |

| Title X | L | Establishes the Community Relations Service to assist in community disputes regarding discrimination | |

| Voting Rights Act (1965) | L | all U.S. residents | Removed requirements for voting, e.g., literacy tests, that had restricted access to voting by racial groups. |

| Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA, 1965) | L | schools | Directed to assure equal opportunities for education to low income neighborhoods by supplementing financial resources. |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Act (1972), Amends CRA, Title VII | L | all U.S. residents | Expands non-discrimination policy to employers with 15–25 employees. |

| Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (1989) | L | banks | Requires banks to track not only census tracts where they made loans, but also of the characteristics of borrowers and applicants. |

Civil rights laws and rulings commonly designate or apply to a protected class: “A class of individuals to whom Congress or a state legislature has given legal protection against discrimination or retaliation.” (https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/protected_class).

The first civil rights law was enacted in 1866 – “An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication.” The Fourteenth Amendment (1868) established that every individual born or naturalized in the United States is a citizen, and ensured that states may not deprive a citizen or resident of civil rights, including due process of law and equal protection Chemerinsky (2006). The Fifteenth Amendment (1870) granted citizenship and voting rights to freed (male) slaves and their (male) descendants. Thus the civil rights and constitutional protections guaranteed to White Americans in the Constitution and amendments were theoretically available to Black Americans and other racial-ethnic minority Americans; for American Indians, only those not living in “Indian territories” were included. American Indians were given citizenship only in the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

However, the notion of equality was contested. In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court confirmed the “separate but equal principle” that sanctioned segregation practices, until those practices were outlawed in Brown in 1954. Although segregation in education was ruled illegal, the practice persisted Fiel (2013).

Particularly in southern states, “Jim Crow” laws were enacted, legally enforcing segregated institutions and depriving Americans and others of civic participation by various means. Implementation of the Fifteenth Amendment was impeded for almost a century (1870–1970) as poll taxes, qualification tests, and other requirements limited access to the vote Zinn (2014). The Social Security Act (1935) excluded agricultural workers and domestic servants, which, at the time constituted three fifths of the Black labor force Quadagno (2000). Governmental and official law enforcement efforts to deny Black Americans their civil rights guaranteed by the Constitution persisted at least until the 1950s when, beginning with Brown, organized efforts to dismantle Jim Crow laws began to work. In the expansion of civil rights in U.S. history, states have played leading roles (Tarr, 1990, Hudnut, 1985, Brennan, 1977).

Effects of civil rights law and enforcement on the health of racial and ethnic minority populations since 1950

Here we provide examples of evidence of the effects of enforcing civil rights court rulings and legislation enacted in the past 65 years in 4 domains—health care, education, employment, and housing. We chose these domains to illustrate with strong examples the effects of civil rights law on public health. Those effects are likely to also apply in other civil domains, such as justice, civic participation, and transportation. While court rulings and legislation are often refined and modified over time, we focus on the original legislation or ruling and on the research assessing its consequences. When assessed, we report health outcomes. We also report outcomes such as educational achievement, income, and employment because these outcomes are basic social determinants of health. When a social determinant of health is improved in a population, so is population health (Hahn & Truman 2015; Acevedo-Garcia and Osypuk, 2008, American Public Health Association, 2010; Binswanger, Redmond, Steiner & Hicks, 2012). While systematic review of this topic is needed, the goal here is to provide illustrative examples of evidence of the effects of civil rights laws on public health in recent history. We conducted searches for civil rights and health, focusing on civil rights law on each subtopic (in PubMed, Google, and Google Scholar); we also searched reference lists. We found few studies and none indicating negative health effects of civil rights laws or rulings.2 Public health law studies have largely focused on laws explicitly addressing public health, and, published literature has not examined the effects of civil rights laws and their enforcement (Moulton et al., 2009; Gostin, Wiley & Frieden, 2015). While our hypothesis that the public health benefits of the implementation of civil rights laws can be large and long term probably applies to several racial and ethnic minority populations, most of the studies we found examined effects on black populations.

Civil rights and health care

By the mid-1960s, the Hill-Burton Act (1964) had financed the construction of hospitals in the US with almost half of hospital beds in the nation Almond, Chay, and Greenstone (2006). The Act explicitly followed the principle of “separate but equal” even after Brown invalidated this principle in education. It allowed jurisdictions to construct hospitals restricted to Whites as long as comparable facilities for Blacks could be demonstrated Quadagno (2000). In Alabama, Hill-Burton funds supported the construction of hospitals in 67 counties, only two of which had non-segregated services Quadagno (2000). The North Carolina case, Simkins v. Cone, 323 F.2d 959 (1963) held the “separate but equal” provision of the Hill-Burton Act unconstitutional. Studies have focused on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA) prohibiting segregation and discrimination in hospitals receiving federal funds (Almond et al.,2006; Chay & Greenstone 2000; Krieger, Chen, Coull, Waterman & Beckfield, 2013).

Medicare (established July 1966) tied the receipt of federal funds for low income patients to non-discrimination and non-segregation, thus providing strong incentive for compliance with the CRA. Nevertheless, resistance continued in many southern states Smith (1999). Part of the resistance to desegregation took the form of claims that hospitals were private and exempt from federal regulation. Quadagno argues that it was pressure from the welfare state through Medicare and enforcement of its anti-discrimination provisions that brought hospitals into compliance with CRA desegregation principles Quadagno (2000). However, enforcement of Title VI has been partial and inconsistent Yearby (2014).

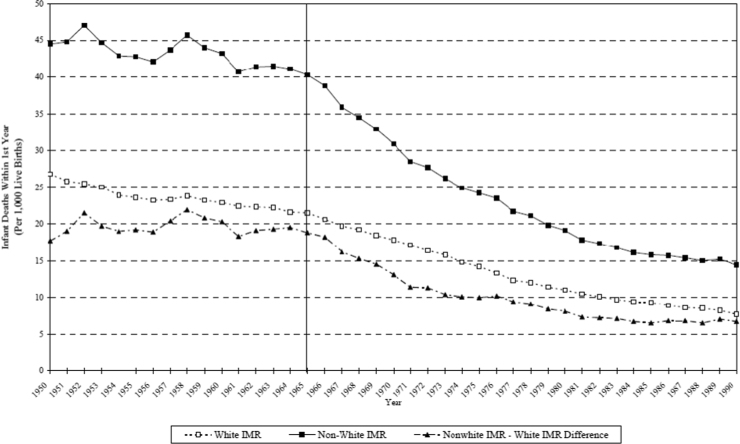

Almond et al., (2006) used national infant mortality data (an indicator of population health (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016)) to assess the association between Title VI of the CRA and infant mortality rate (IMR) trends; they focus on IMR from diarrhea and pneumonia, which account for a large proportion of hospital treatment for infants. Most changes occurred in southern states in which hospital segregation was previously widespread. In the United States overall, between 1965 and 1971, the IMR among nonWhites (approximately 99% of whom were Black) fell by 40% from 40 to 28 per 1,000 live births (Fig. 2), while the rate among Whites changed little and the nonWhite:White IMR ratio fell from 1.90 to 1.65—the largest decline since World War II Almond et al., (2006). The concurrence of the timing, abruptness of the rate changes following 1964, the sharp decline in death from infant conditions treatable in hospital settings, and the contrast with minimal changes among Whites suggests the CRA as the cause of these trends. The researchers estimate that, between 1965 and 2002, approximately 38,600 Black infant deaths were prevented by implementation of Title VI of the CRA (Almond et al., 2006; Chay & Greenstone 2000).

Fig. 2.

NonWhite and White Infant Mortality and NonWhite and White Infant Mortality Difference per 1,000 Live Births, United States, 1950–1990 (from Vital Statistics of the United States).

Using the same reasoning, the same researchers examined the childbearing outcomes among adult daughters of Black and White women born between 1955 and 1975 to assess whether the CRA was also associated with the childbearing of these women and their daughters born in the 1980s and 1990s Almond and Chay (2006). Black women born in the late 1960s were less likely to have low birthweight infants or infants with low APGAR scores (indicating poor health and the need for immediate medical care) than women born earlier, while no similar changes were found for White women. Thus, not only were Black infants born after the CRA healthier than those born before, but their next generation descendants were also healthier Chay and Greenstone (2000).

Krieger et al. (2013) confirm these findings. They classify all states prior to the CRA as “Jim Crow polities” or not, based on whether state laws legalized racial discrimination in one or more of several domains, including education, transportation, hospital and penal institutions, and employment. This classification avoids the assumption that only Southern states had segregationist policies and adds Kansas and Wyoming as Jim Crow states. The researchers find that the ratio of Black infant mortality rates in Jim Crow versus non Jim Crow states fell from 1.19 from 1960 through 1964 to 1.0 from 1970 until 2000, with no changes in similar comparisons for White infants. The finding suggests health disparities in infant mortality between states with and without Jim Crow laws were eliminated following enactment and enforcement of the CRA Krieger et al. (2013). Krieger similarly reports an association between birth in states with Jim Crow laws and rates of estrogen negative breast cancer among black, but not among white women (Krieger, Jahn & Waterman, 2017), thus again suggesting a negative effect of the absence of civil rights enforcement.

Available evidence suggests that the CRA greatly affected infant mortality rates among blacks previously excluded from full access to hospital resources and probably affected the health of the succeeding generation as well.

Civil rights and education

In the early 20th century, substantially different educational resources were provided for black and white children. For example, in Alabama, resources were markedly less for Black than for White students Margo (1985). Such blatant forms of discrimination in education, and specifically the concept of “separate but equal,” were ruled unconstitutional in the 1954 Brown decision.

In a remarkable study of both the immediate and long term effects of school desegregation, Johnson (Johnson, 2011) analyzed all U.S. court school desegregation orders issued between 1954 and 1970 and their effects on children born between 1945 and 1968, assessed up to 2011. He evaluated effects on school resources, high school completion and other educational outcomes, as well as adult earnings and health. Johnson controlled for an array of potential confounding, comparing siblings exposed and not exposed (having completed school prior to desegregation) to court ordered desegregation, also controlled for policies related to the War on Poverty, and Head Start, and community political affiliations associated with segregationist policies.

Johnson found that, following the 868 school desegregation orders, there was a notable increase in school district integration; the dissimilarity index (ranging from 0—no segregation to 1—complete segregation) fell from the 1968 mean of 0.83 to the substantially lower mean of 0.20 within 7 years. Four years following the court-ordered desegregation, there was also a mean increase of $1000 in per student expenditures – principally in high proportion Black school districts.

The increase of $1000 in school funding per student was associated with “an additional 1.4 years of completed education, a 58% increase in wages, an increase of $18,635 in annual family income, a 34% reduction in the annual prevalence of adult poverty, and a 2.1% reduction in the annual incidence of adult incarceration”—among Black students, with little change for White students. Finally, the gap in adult self-assessed health status between Blacks and Whites was reduced by between one third and one half.

Johnson also finds that, for each year that a Black student spends in a desegregated school, the student is 2% more likely to graduate from high school. Thus, exposure to desegregated schools for 12 years would be expected to result, on average, in a 24% (i.e., 2%/year over 12 years) increase in the likelihood of graduation--approximately equivalent to the gap in Black and White graduation rates during the study period Trends (2013). Thus, it is possible that much of the infamous gap between Blacks and Whites in academic achievement is attributable to school segregation and that countering segregation is part of the solution to this persistent and consequential problem. It is estimated that in the year 2000, compared with those with a high school education or more, failure to complete high school was associated with between 23% and 81% greater likelihood of death per year Galea, Tracy, Hoggatt, DiMaggio, and Karpati (2011).

There was little change in school segregation following Brown until the late 1960s, followed by a substantial decline in segregation at least until the mid-1980s Reardon and Owens (2014). In recent decades, the Executive Branch of the federal government, and in particular, the U.S. Department of Education and its Office of Civil Rights, have increasingly limited their efforts in promoting school desegregation (Le Chinh, 2009, Epperson, 2008), thus slowing the potential contributions of desegregation to the health and well-being of many racial/ethnic minority students.

Civil rights and labor, employment

Title VII of the CRA of 1964 made it illegal for employers to “fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions or privileges or employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” Establishments and firms with ≥100 employees were covered as of July 2, 1965; covered entities were incrementally expanded until, in 1972, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act amended Title VII to add establishments and firms with 15–25 employees. While most states had already adopted their own anti-discrimination regulations, this was not the case in eight southern states.

Chay (1998) assessed the effect of the 1972 addition of the 15–25 employee category on the relative employment and wages of Black men compared with White men in southern and northern states. Following enactment of the new requirements, the relative employment of Black men increased by between 0.5% and 1.1% per year more rapidly than prior to the new law, as did the range of their occupations and their wages.

Similarly, Kaplan, Ranjit, and Burgard (2008) assessed the consequences of anti-discrimination provisions on employment opportunities, wages, and life expectancy of Black women from 1950 to 1980. The researchers analyzed trends before and after 1964 and compared northern and southern states. The proportion of Black women reporting household service work in southern states declined from >50% to <20%, and, by 1980 the proportion of Black women reporting white-collar employment had increased by approximately 200% in the south and 300% in the north. In contrast, white-collar employment among White women increased by 17% in the south and 7% in the rest of the nation Kaplan et al. (2008). Similarly, while in 1960, the wages of Black women were 64% of those of White women, by 1980, wages were almost equal. From 1966 through 1975, life expectancy for a Black woman aged 35 years increased 2.6 years, while that of White women increased only 1.5 years.

Major trends and contrasts in employment, occupational levels, and wages centered on 1964, the year of the CRA, are consistent with the hypothesis that the CRA substantially benefited the employment opportunities and long term health of Black men and women. Employment is a recognized predictor of self-assessed health (Ross & Mirowsky, 1995) and a strong indicator of long term health and mortality (Idler & Benyamini); unemployment is a risk factor for mortality Roelfs, Shor, Davidson, and Schwartz (2011).

Civil rights, place of residence, and home ownership

Housing is a basic human need, providing shelter and, with home ownership, investment and security. In addition, the location of one’s home is a major determinant of access to community resources, including safety and recreation, food and other material goods, and transportation, employment, and education which are themselves social determinants of health. Through multiple causal pathways, the quality, location, and value of housing are major determinants of health Acevedo-Garcia and Osypuk (2008). However, while laws prescribe standards of non-discrimination, implementation has been minimal and inconsistent.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 had guaranteed each male citizen an equal right “to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property,” and the Fourteenth Amendment affirmed equal rights under law. Fulfillment of these rights was long delayed. Realtors, licensed by the states to control the acquisition of housing, are responsible for informing, showing, and assisting in the purchase of available homes, as well as in the procurement of mortgages. At each phase, realtors may facilitate or restrict access to desirable housing by clients of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Until at least 1950, the manual of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, recommended that:

“The realtor should not be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality or any individual whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood” (United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1973).

Realtors thus enforced “restrictive covenants”—agreements among residents of communities that explicitly excluded racial and ethnic minority or foreign-born residents. In 1917, the Supreme Court declared these agreements unconstitutional (Buchanan v. Warley 245 US 60, 38 S. Ct. 16, 62 L. Ed. 149); however the practice continued. The mortgage insurance program promoted by the Federal Housing Administration, established in 1934, advised, “If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same racial classes.” In 1973, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1973) described the realty enterprise as a process “in which the Government and private industry came together to create a system of residential segregation,” a finding recently documented in detail Rothstein (2017). In 1948, in Shelley v. Kraemer, the Supreme Court declared that enforcement of these agreements was unconstitutional United States Commission on Civil Rights (1973). However, as of 1973, subsequent studies indicated that, “Blacks have made very little progress in reducing segregation in housing since … Shelley v. Kraemer” (United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1973).

Additional federal laws and Supreme Court decisions that established expanded opportunities for fulfillment of civil rights regarding housing have also been minimally enforced. The Fair Housing Act (Title VII of the CRA of 1968) “…prohibited discrimination on the basis of ‘race, color, religion, or national origin’ in the sale or rental of housing, the financing of housing, or the provision of brokerage services” (Feder, 2003). Supreme Court case Jones V Mayer, 1968, extended coverage of the prohibitions to private properties. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was established in 1965 to promote housing and urban development “in a manner affirmatively to further the purposes of fair housing.” HUD conducts periodic surveys of discrimination in the acquisition of housing by the race, ethnicity, and other characteristics of potential purchasers or renters. Black, Hispanic, White, and Asian interviewers pose as renters or purchasers with equal qualifications; they record available housing they are informed of or shown. In the most recent survey (2012), Black interviewers were informed of 17% fewer homes and shown 17.7% fewer homes than Whites Turner (2013). Asians were informed of 15.5% fewer homes and shown 18.8% fewer homes. Similar findings were reported in 1977 Wienk (1979).

Housing civil rights enforcement actions may be brought by the Attorney General, HUD, or plaintiffs. Only a miniscule proportion of instances of housing discrimination are investigated or remedied. Most instances of racial discrimination occur with impunity. Simonson (2004) estimates that approximately 1,760,000 incidents of discrimination against Black home-seekers occur annually. HUD investigates several thousand claims of racial discrimination and initiates several suits annually; in 2014, there were fewer than 4,000 claims brought for racial discrimination (US Development UDoHaU, 2014) — about 0.2% of Simonson’s estimate. In Hills, Secretary of HUD v. Gautreaux et al., the Supreme Court ruled in 1976 that: “…HUD has been judicially found to have violated the Fifth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in connection with the selection of sites for public housing …” (United States Supreme Court., 1976). Overall, Black home ownership in the U.S. is 25% lower than of that of Whites and the gap increased slightly from 1970 to 2001; only among those with the highest income did the gap decrease (from 13.9% to 11.9%) Herbert (2005).

HUD has been repeatedly sued for failure to effectively pursue its own fair housing mandates Ellen and Yager (2015). The Gautreaux decision required the Chicago public housing authority to give vouchers to qualified recipients of public housing benefits in low income, segregated areas of Chicago. Participants who moved to higher income suburbs were more likely to be employed and their children had improved educational outcomes Rosenbaum and Zuberi (2010). Better-designed studies of programs such as Moving to Opportunity have found benefits for low income recipients—including improvements in housing, employment, and reductions in obesity, diabetes risk, and alcohol abuse (Sanbonmatsu et al. 2011; Fauth, Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Ludwig et al., 2011).

Three recent events indicate crucial opportunities for increased civil rights in housing. In the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. (135 S. Ct. 2507 (2015)) case, the Supreme Court affirmed the purpose of the Fair Housing Act as the advancement of racial integration, and chastised federal and local governments for exacerbating rather than remedying residential segregation Roisman (2015). The Court ruled that disparate impact discrimination violates the Fair Housing Act and noted: “Much progress remains to be made in our Nation’s continuing struggle against racial isolation.” Similarly, the Obama administration announced efforts to strengthen and enforce federal fair housing policies forbidding residential discrimination in the location of public housing projects Davis and Applebaum (2015). Finally, HUD’s Plan for 2014-8, noting that “housing discrimination still takes on blatant forms in some instances,” indicated as one of its objectives to “reduce housing discrimination, affirmatively further fair housing through HUD programs, and promote diverse, inclusive communities” (US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2014).

Discussion

Examination of consequences of the historical denial of the civil rights of racial and ethnic minority populations and the effects of civil rights laws, Supreme Court decisions, and implementation, including enforcement actions to right those wrongs, indicates that civil rights can be a powerful social determinant of health. Deprivation of civil rights has been a prominent factor in the poor health of Black people in the United States. Protection of civil rights of racial and ethnic minorities by laws, regulations, and court decisions and redress of violations of those rights have been associated with marked improvements in the health of covered populations and of intermediate outcomes such as education and income known to produce health benefits.

However, also clear from evidence showing the limited consequences of housing civil rights legislation, public health benefits depend not only on the existence of civil rights and regulations, but on their implementation, including their enforcement. Unless implemented, civil rights are promises without benefit. While the scope of efforts to protect civil rights has greatly expanded in recent history, evidence presented here and elsewhere (Reskin, 2012, Smith, 1999, Chemerinsky, 2002) shows that enforcement of civil rights has been uneven and incomplete, and, at least in domains of health care, education, and housing, resistance to civil rights laws and their implementation persists.

The public health benefits of civil rights implementation can be large and long term. Civil rights thus may be considered a productive arena for public health theorizing, research, policy, action, and practice. Systematic evaluation of the health consequences of civil rights law and surveillance of law enforcement and its consequences will expand basic knowledge. As public health promotes food safety and seat belts, the public health community can also promote fair housing and school desegregation for public health. The public health community has the opportunity to collaborate with agencies responsible for the enactment and enforcement of civil rights, promoting civil rights as a means of advancing public health and reducing health inequities.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ethical statement

This study did not involve subject participation or ethical issues.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest in this study.

Footnotes

Civil rights laws and rulings commonly designate or apply to a protected class: “A class of individuals to whom Congress or a state legislature has given legal protection against discrimination or retaliation.” (https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/protected_class)

Legal scholar, Ruqaiijah Yearby (Associate Dean of Institutional Diversity and Inclusiveness, David L. Brennan Professor of Law, and Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University) reports not being aware of any studies of the public health consequences of civil rights law with either no effects or negative effects.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D., Osypuk T. Invited commentary: Residential segregation and health—the complexity of modeling separate social contexts. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(11):1255–1258. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D., Osypuk T.L. Impacts of housing and neighborhoods on health: Pathways, racial/ethnic disparities, and policy directions. Segregation: The rising costs for America. 2008:197–236. [Google Scholar]

- Almond D., Chay K.Y. University of California-Berkeley; mimeograph: 2006. The long-run and intergenerational impact of poor infant health: Evidence from cohorts born during the civil rights era. [Google Scholar]

- Almond D., Chay K., Greenstone M. (2006). Civil rights, the war on poverty, and black-white convergence in infant mortality in the rural South and Mississippi. In MIT Department of Economics Working Paper.

- American Public Health Association (2010). The Hidden Health Costs of Transportation. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Binswanger I., Redmond N., Steiner J., Hicks L. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: An agenda for further research and action. Journal of Urban Health. 2012;89(1):98–107. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports. 2014;129(1_suppl2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan W., Jr State constitutions and the protection of individual rights. Harvard Law Review. 1977:489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Chay K. The impact of federal civil rights policy on black economic progress: Evidence from the equal employment opportunity act of 1972. Industrial Labor Relations Review. 1998;51(4):608–632. [Google Scholar]

- Chay K., Greenstone M. The convergence in black-white infant mortality rates during the 1960’s. American Economic Review. 2000:326–332. [Google Scholar]

- Chemerinsky E. Aspen Publishers; New York,(NY): 2006. Constitutional law, principles and policies (introduction to law series) [Google Scholar]

- Chemerinsky E. Segregation and resegregation of american public education: The court’s role. NCL Rev. 2002;81:1597. [Google Scholar]

- Clark K.B. The pathos of power: A psychological perspective. American Psychologist. 1971;26(12):1047. [Google Scholar]

- Coates T.-N. Random House; New York: 2015. Between the world and me. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Applebaum B. Obama unveils stricter rules against segregation in housing New York Times July 8, 2015.

- Ellen I.G., Yager J. Race poverty, and federal rental housing policy. HUD at 50: Creating Pathways to Opportunity. 2015:103. [Google Scholar]

- Epperson L. Undercover power: Examining the role of the executive branch in determining the meaning and scope of school integration jurisprudence. Berkeley J African American Law and Policy. 2008;10:146. [Google Scholar]

- Fauth R., Leventhal T., Brooks-Gunn J. Short-term effects of moving from public housing in poor to middle-class neighborhoods on low-income, minority adults' outcomes. Social Science Medicine. 2004;59(11):2271–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder J. (2003). The fair housing act: A legal overview. In; 2003: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

- Feinstein L., Sabates R., Anderson T., Sorhaindo A., Hammond C. Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI); 2006. What are the effects of education on health?: Organisation for economic co-operation and development. [Google Scholar]

- Fiel J. Decomposing school resegregation social closure, racial imbalance, and racial isolation. American Sociological Review. 2013;78(5):828–848. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Tracy M., Hoggatt K.J., DiMaggio C., Karpati A. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1456–1465. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B., Shaw M., Lawlor D.A., Lynch J.W., Smith G.D. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1) Journal of Epidemiology Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B., Shaw M., Lawlor D.A., Lynch J.W., Smith G.D. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2) Journal of Epidemiology Community Health. 2006;60(2):95–101. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner B.A. Thompson West Group; Eagan, Minnesota: 2004. Black’s law dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L.O., Wiley L.F., Frieden T.R. Univ of California Press; 2015. Public health law: Power, duty, restraint. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn R.A. Yale University Press; New Haven, Connecticut: 1995. Sickness and healing: An anthropological perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn R.A., Truman B.I. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. International Journal of Health Services. 2015;45(4):657–678. doi: 10.1177/0020731415585986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert C.E. Office of Development and Research; 2005. Homeownership gaps among low-income and minority borrowers and neighborhoods. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. University of Iowa Press; Iowa City, Iowa: 1996. History, power, and identity: ethnogenesis in the Américas, 1492–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hudnut P. State constitutions and individual rights: The case for judicial restraint. Denv Univ Law Rev. 1985;63:85. [Google Scholar]

- Idler E., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven. [PubMed]

- Johnson R. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2011. Long-run impacts of school desegregation & school quality on adult attainments. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G., Ranjit N., Burgard S., editors. Lifting gates, lengthening lives: Did civil rights policies improve the health of African American women in the 1960s and 1970s. Russell Sage Foundation Publications; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N., Jahn J.L., Waterman P.D. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: US-born black and white non-Hispanic women, 1992–2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(1):49–59. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N., Chen J., Coull B., Waterman P., Beckfield J. The unique impact of abolition of Jim Crow laws on reducing inequities in infant death rates and implications for choice of comparison groups in analyzing societal determinants of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(12):2234–2244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Chinh Q. Racially integrated education and the role of the federal government. North Carolina Law Rev. 2009;88:725–785. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J., Sanbonmatsu L., Gennetian L., Adam E., Duncan G., Katz L. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—A randomized social experiment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(16):1509–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margo R. National Bureau of Economic Research; 1985. Education achievement in segregated school systems: The effects of” Separate-But-Equal”. [Google Scholar]

- Moulton A.D., Mercer S.L., Popovic T., Briss P.A., Goodman R.A., Thombley M.L. The scientific basis for law as a public health tool. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(1):17–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omi M., Winant H. Routledge; New York, NY: 2014. Racial formation in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Quadagno J. Promoting civil rights through the welfare state: How medicare integrated southern hospitals. Social Problems. 2000;47(1):68–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S.F., Owens A. 60 years after Brown Trends and consequences of school segregation. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014;40:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Reskin B. The race discrimination system. Annual Review of Sociology. 2012;38:17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs D.J., Shor E., Davidson K.W., Schwartz J.E. Losing life and livelihood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Social science medicine. 2011;72(6):840–854. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman F. The power of the supreme court’s decision in the fair housing act case, inclusive communities project Inc. v. Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs Poverty and Race. 2015;24:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J., Zuberi A. Comparing residential mobility programs: Design elements, neighborhood placements, and outcomes in MTO and Gautreaux. Housing Policy Debate. 2010;20(1):27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C.E., Mirowsky J. Does employment affect health? Journal of Health and social Behavior. 1995:230–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C., Wu C. The links between education and health. American Sociological Review. 1995:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. WW Norton; New York, N.Y.: 2017. The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. [Google Scholar]

- Sanbonmatsu L., Ludwig J., Katz L., Gennetian L.A., Duncan G., Kessler R. Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research; 2011. Moving to opportunity for fair housing demonstration program – Final impacts evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Simonson J. (2004). National estimates of annual discrimination against black households in U.S. rental and sales markets: Center for Applied Public Policy UW-Platteville; January.

- Smedley B.D., Stith A.Y., Nelson A.R. (2002). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care National Academies Press. [PubMed]

- Smith D.B. University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 1999. Health care divided: Race and healing a nation. [Google Scholar]

- Steckel R.H. A peculiar population: The nutrition, health, and mortality of American slaves from childhood to maturity. The Journal of Economic History. 1986;46(3):721–741. doi: 10.1017/s0022050700046842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr G. Constitutional theory and state constitutional interpretation. Rutgers Law J. 1990;22:841–861. [Google Scholar]

- Trends P.S. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2013. King’s dream remains an elusive goal; many americans see racial disparities.〈http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/08/22/kings-dream-remains-an-elusive-goal-many-americans-see-racialdisparities〉 [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research; 2013. Housing discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities 2012: U.S. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Infant Mortality. In. 〈http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm〉.

- United States Commission on Civil Rights (1973). Understanding fair housing.

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development (2014). FY 2014–2018 HUD Strategic Plan.

- US Department of Housing and Development. Fiscal Year 2012-2013 Annual Report on the State of Fair Housing in America: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2014.

- United States Supreme Court (1976). Carla A. Hills, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development V. Dorothy Gautreaux Et Al: Selection of Sites for Public Housing in the Chicago Area are Racially Discriminatory: University of the State of New York, State Education Department, New York State Library, Legislative Research Service.

- Waldstreicher D. Hill and Wang; 2010. Slavery’s constitution: From revolution to ratification. [Google Scholar]

- Wienk R. Division of Evaluation, U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research; Washington, DC: 1979. Measuring racial discrimination in American housing markets: The housing market practices survey. [Google Scholar]

- Williams H.A. Oxford University Press; 2014. American slavery: A very short introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Costa M.V., Odunlami A.O., Mohammed S.A. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. Journal of public health management and practice. 2008;14(Suppl):S8. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health.

- Yearby R. When is a change going to come: Separate and unequal treatment in health care fifty years after the title vi of the civil rights act of 1964. SMUL Rev. 2014;67:287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn H. Pan Macmillan; 2014. A people’s history of the United States. [Google Scholar]