Abstract

Although acellular cementum is essential for tooth attachment, factors directing its development and regeneration remain poorly understood. Inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), a mineralization inhibitor, is a key regulator of cementum formation: tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (Alpl/TNAP) null mice (increased PPi) feature deficient cementum, while progressive ankylosis protein (Ank/ANK) null mice (decreased PPi) feature increased cementum. Bone sialoprotein (Bsp/BSP) and osteopontin (Spp1/OPN) are multifunctional extracellular matrix components of cementum proposed to have direct and indirect effects on cell activities and mineralization. Studies on dentoalveolar development of Bsp knockout (Bsp−/−) mice revealed severely reduced acellular cementum, however underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The similarity in defective cementum phenotypes between Bsp−/− mice and Alpl−/− mice (the latter featuring elevated PPi and OPN), prompted us to examine whether BSP is operating by modulating PPi-associated genes. Genetic ablation of Bsp caused a 2-fold increase in circulating PPi, altered mRNA expression of Alpl, Spp1, and Ank, and increased OPN protein in the periodontia. Generation of a Bsp knock-out (KO) cementoblast cell line revealed significantly decreased mineralization capacity, 50% increased PPi in culture media, and increased Spp1 and Ank mRNA expression. While addition of 2 μg/ml recombinant BSP altered Spp1, Ank, and Enpp1 expression in cementoblasts, changes resulting from this dose were not dependent on the integrin-binding RGD motif or by genetic ablation of Ank on the Bsp−/− MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Decreasing PPi mouse background reestablished cementum formation, allowing more than 3-fold increased acellular cementum volume compared to WT. However, deleting Ank did not fully compensate for the absence of BSP. Bsp−/−;Ank−/− double-deficient mice exhibited mean 20–27% reduced cementum thickness and volume compared to Ank−/− mice. From these data, we conclude that the perturbations in PPi metabolism are not solely driving the cementum pathology in Bsp−/− mice, and that PPi is more potent than BSP as a cementum regulator, as shown by the ability to override loss of BSP by lowering PPi. We propose that BSP and PPi work in concert to direct mineralization in cementum and likely other mineralized tissues.

MeSH key words: Extracellular Matrix, Tooth Calcification, Dental Cementum, Periodontium, Odontogenesis, Bone

1. Introduction

The periodontal complex functions to attach and support the tooth, and includes cementum, periodontal ligament (PDL), and alveolar bone [1]. Cementum is a thin mineralized tissue on the root surface that is present as acellular cementum on the cervical root and cellular cementum around the root apex. Acellular cementum is essential for anchoring PDL collagen fibers to the root surface. Cementum and bone share regulatory pathways and key developmental influences as evidenced by mouse genetic studies and human disease phenotypes [2–4]. However, accumulated evidence over the past two decades has revealed that acellular cementum is hypersensitive to regulators of mineralization, apparently more so than other hard tissues of the dentition and skeleton [5–7].

The first developmental disease understood to affect cementum was hypophosphatsia (HPP; OMIM 241500, 241510, 146300), an inherited error-of-metabolism caused by loss-of-function mutations in ALPL, the gene that encodes tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) [8, 9]. In HPP, loss of TNAP function results in increased concentrations of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) that is a potent inhibitor of physiological and pathological mineralization. HPP causes disturbed skeletal mineralization, including rickets and osteomalacia. In the teeth, HPP appears to disturb dentin and enamel mineralization, but more severely blocks formation and function of acellular cementum in both human subjects and mouse models, leading to PDL detachment and premature tooth loss [2, 10–16].

While TNAP functions to decrease extracellular PPi concentrations, other proteins counteract this activity. The progressive ankylosis protein (Ank/ANK) regulates transport of PPi out of the cell to the extracellular space [17–19], while extracellular pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (Enpp1/ENPP1) hydrolyzes extracellular nucleotide triphosphates to produce PPi [20, 21]. Mice lacking either ANK or ENPP1 activity (Ank−/− and Enpp1−/− mice, respectively) feature decreased extracellular PPi production/secretion and are predisposed to ectopic calcification [17, 19, 22, 23]. In the absence of ANK or ENPP1, acellular cementum is dramatically increased, pointing to PPi as a central regulator tuning cementum growth and mineralization [5–7]. Additional examples of the sensitivity of acellular cementum to disturbances in mineralization come from studies of endocrine disorders like X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH; OMIM 307800) [24, 25] and autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR; OMIM 241520) [26], transgenic mouse models over-expressing mineralization inhibitors like matrix gla protein [27], or administration of pharmacologic agents such as etidronate, a synthetic PPi analog [28–30], where acellular cementum formation and function are negatively affected.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of cementum is rich in phosphoproteins, including bone sialoprotein (BSP/Bsp) and osteopontin (OPN/Spp1), both members of the Small Integrin-Binding Ligand N-linked Glycoprotein (SIBLING) family, ECM phosphoproteins associated with mineralized tissues [31–33]. Bsp mRNA is expressed constitutively by cementoblasts during root formation and BSP protein has been localized throughout the thickness of the acellular and cellular cementum layers [6, 34–38]. While BSP has been used as a marker of cementoblasts and cementum, its importance was not appreciated until detailed studies of dentoalveolar development in Bsp−/− mice revealed significantly reduced and nonfunctional acellular cementum, resulting in dysfunctional PDL attachment and periodontal breakdown [34, 39, 40]. While the dependence of proper cementum formation on BSP is apparent, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Like other SIBLINGs, BSP is a multifunctional protein with several highly conserved functional motifs, including an N-terminal collagen and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) binding domain, two to three (depending on species) highly negative polyglutamic acid (polyE) stretches thought to nucleate hydroxyapatite crystal formation, and a C-terminal arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) integrin-binding domain that can promote cell signaling, attachment, and migration [33, 41, 42]. BSP undergoes post-translational modifications including serine/threonine phosphorylation, N- and O-linked glycosylation, and tyrosine sulfation, however, is not known to undergo proteolytic processing [41, 43–45]. Phosphorylation of a serine residue adjacent to one of the polyE domains (Ser136 in rat BSP) was found to be important in the nucleation of hydroxyapatite crystal by BSP [45]. OPN, a protein closely related to BSP, has been shown to have direct inhibitory effects on mineralization, as well as indirect effects by regulating PPi metabolism through modulation of expression of Ank, Enpp1, and Alpl, and by being a PPi-responsive gene [23, 46–52].

The demonstrated potency of BSP polyE domains to promote hydroxyapatite crystal nucleation and growth [50, 53–57], coupled with the sensitivity of cementum to mineralization disturbances, suggested as one hypothesis that BSP may be directly involved in initiation and/or growth of hydroxyapatite mineral in the cementum ECM. The similarity in defective cementum phenotypes between Bsp−/− mice and Alpl−/− mice, that feature elevated PPi and OPN, prompted us to examine whether BSP may be operating indirectly by modulating genes that control PPi metabolism. We used multiple approaches to test the effects of BSP on systemic and local PPi regulatory factors. These included Bsp−/− mice, as well as mice deficient for both Bsp and Ank, to test whether decreased PPi would restore cementogenesis. A novel Bsp knock-out cementoblast cell line was employed to analyze mechanisms in a controlled in vitro environment.

2. Results

2.1. Altered pyrophosphate metabolism in Bsp−/− mice

Bsp−/− mice feature acellular cementum deficiency, though not a complete absence, resulting in periodontal ligament (PDL) detachment and periodontal destruction, as we have reported previously [34, 39, 40] (Figure 1-D). To identify the effects on the periodontal structures associated with changes in Pi/PPi regulators and other factors, we first analyzed gene expression in tooth-associated periodontal tissues by quantitative PCR (QPCR) array. At 5 dpn, out of 84 genes included in the array, no mRNA changes in Bsp−/− vs. WT periodontia reached the threshold of ± 2-fold difference and p < 0.05 (Appendix Table 1). At 14 dpn, only Sp7 (Osterix) and Runx2 showed significant differences in Bsp−/− vs. WT, with 2.7-fold (p = 0.02) and 2.9-fold (p = 0.02) decreases vs WT, respectively (Appendix Table 2). By 26 dpn (at completion of root length and during cellular cementum formation), 15 genes in Bsp−/− were significantly up-regulated and 7 genes were significantly down-regulated (>2-fold) in comparison to age-matched WT tissues (Table 1 and Appendix Table 3). At this age, transcription factors Runx2 and Sp7 were both increased 3 to 6-fold (p < 0.01) in Bsp−/− over WT tissues. Several altered genes indicated dysregulation in Wnt pathway signaling in Bsp−/− mice, including Ctnnb1 (3.8-fold), Lrp6 (3.2-fold increase), and Dkk1 (12.2-fold decrease). A 2.9-fold increase in Smad4 and 6-fold increase in Bgn (Biglycan) implicated increased TGF-β signaling in Bsp−/− vs. WT periodontia. Two integrins and potential ligands for the BSP RGD motif, Itgav and Itga4, were significantly down-regulated (2- and 21-fold, respectively) in Bsp−/− compared to WT tissues.

Figure 1. Altered gene expression and pyrophosphate metabolism in Bsp−/− mice.

Compared to normally developing mandibular first molar acellular cementum (AC) in (A, B) WT mice, molars in (C, D) Bsp−/− mice exhibit AC deficiency (red *) and periodontal ligament (PDL) detachment (red #). (E) QPCR array performed on (n=3) periodontal tissues from Bsp−/− vs. WT mice at 26 dpn identifies increased (p < 0.05 by t-test) Alpl, Spp1, and Ank mRNA. (F) Plasma pyrophosphate (PPi) levels are increased significantly (p < 0.05 by t-test) in (n=4–8) Bsp−/− vs. WT mice at 14 but not 26 dpn. (G) No significant differences are observed in circulating OPN levels in (n=5) Bsp−/− vs. WT mice at 14 and 26 dpn (p > 0.05 by t-test). Immunohistochemistry for OPN reveals normal distribution in (H, I) WT AC, PDL, and alveolar bone (AB) at 14 and 26 dpn, while (J, K) Bsp−/− mouse molars feature OPN at the sites of defective AC formation (compare insets in H and J) and AB resorption. DE = dentin.

Table 1. Quantitative PCR comparing gene expression in periodontia of Bsp−/− versus WT mice at 26 dpn.

PCR array was performed on total RNA isolated from periodontal tissues of Bsp−/− and WT mouse molars (n=3 each) at 26 dpn. This table shows relative expression levels (Bsp−/− vs. WT, both normalized to housekeeping genes, in descending order of fold-change) for all genes showing 2-fold or more difference that were significantly up- or down-regulated (p < 0.05). Shading indicates the portion of the table that includes down-regulated factors. The entire gene list and calculated fold changes can be found in Appendix Table 3.

| Gene symbol | Fold-change | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Osterix/SP7 | 6.4464 | 0.004928 |

| Bgn | 6.1981 | 0.008007 |

| Periostin | 5.1047 | 0.016595 |

| Alpl | 4.6006 | 0.001835 |

| Spp1 | 4.2628 | 0.025887 |

| Ctnnb1 | 3.7803 | 0.024016 |

| Runx2 | 3.6769 | 0.00001 |

| Lrp6 | 3.2456 | 0.034124 |

| Ank | 3.135 | 0.015848 |

| Dmp1 | 2.9454 | 0.000892 |

| Smad4 | 2.8782 | 0.03149 |

| RANKL | 2.6979 | 0.003363 |

| Vdr | 2.5289 | 0.020998 |

| Pthr1 | 2.2374 | 0.032302 |

| Abcc6 | 2.0731 | 0.022166 |

| Itgav | −2.0823 | 0.032629 |

| Phospho1 | −2.2839 | 0.005087 |

| Nt5e | −2.5051 | 0.01441 |

| Galnt3 | −5.0918 | 0.025407 |

| Ocn | −5.9033 | 0.007059 |

| Dkk1 | −12.2512 | 0.024818 |

| Bsp | −19.0033 | 0.002106 |

| Itga4 | −21.2322 | 0.010895 |

Especially notable, 3 regulators of PPi in bones and teeth were significantly altered (p < 0.05) in Bsp−/− vs. WT periodontal tissues by 26 dpn (Figure 1E), though none were significantly altered at earlier time points. Alpl was increased 4.6-fold, mirroring increased plasma ALP reported previously [34]. Spp1, encoding osteopontin (OPN), and Ank, were increased 4.3-fold and 3-fold, respectively, in 26 dpn Bsp−/− periodontal tissues. Enpp1 did not show a significant change in expression over WT.

Plasma PPi concentrations were significantly increased (2-fold) in Bsp−/− compared to WT mice at 14 dpn, with no difference at 26 dpn (Figure 1F, G). ELISA performed on plasma indicated no significant difference in mean circulating OPN in Bsp−/− vs. WT mice at both ages (Figure 1G). However, IHC showed that at both early (14 dpn) and later (26 dpn) stages of root development, OPN protein was deposited on molar root surfaces where lack of BSP prompted an acellular cementum defect (Figure 1H–K). While no differences were noted in OPN expression patterns at day 14, by 26 dpn, Bsp−/− PDL and alveolar bone exhibited locally increased OPN immunologic staining when compared with WT tissues.

2.2. Defective mineralization by Bsp knock-out cementoblasts

In order to further define the mechanism(s) by which BSP deficiency promotes defective periodontal mineralization, we generated Bsp knock-out (KO) cementoblasts using a CRISPR nuclease approach (Figure 2A) on an established line of OCCM.30 immortalized murine cementoblasts [6, 58]. An ossicle implant assay was used to evaluate 5 Bsp KO clones (Appendix Figure 1A) compared to WT OCCM.30 parent cells. After 8 wks within collagen sponges implanted subcutaneously in mice, WT cells promoted large ossicles, while Bsp KO cells uniformly produced much smaller ossicles (Appendix Figure 1B). Radiography and high resolution micro-CT indicated Bsp KO ossicles to be less mineralized than WT (Figure 2B, C), and H&E staining revealed that compared to WT, Bsp KO cells produced extensive lightly stained regions suggestive of the appearance of unmineralized cementoid/osteoid (Figure 2D), though other ECM components were not assayed. Quantitative analyses of micro-CT data (Figure 2E, F) confirmed that WT cells promoted a mean 15-fold larger ossicle volume with 13-fold more hydroxyapatite than Bsp KO cells, both statistically significant differences (p < 0.01).

Figure 2. Bsp knock-out cementoblasts exhibit defective mineralization.

(A) Bsp knock-out (KO) OCCM.30 immortalized cementoblasts were created using a CRISPR nuclease approach targeting exons 1–3 (E1-E3) in the mouse Bsp sequence. Compared to WT OCCM.30 parent cells at 8 weeks, Bsp KO cementoblasts produced smaller and less mineralized implants as assessed by (B) radiography and (C) micro-CT. Shown here is one representative implant from n=3–4 per cell line. In 3D micro-CT images shown in (C), gray indicates less mineralized volumes (200–800 mg/cm3 HA) while blue indicates highly mineralized volumes (greater than 800 mg/cm3 HA). (D) Unlike WT implants, H&E stained histological sections reveal regions that appear hypomineralized in Bsp KO implants. Quantitative micro-CT analysis shows a (E) 15-fold significantly greater mean volume and (F) 13-fold significantly greater mean mineral content in WT vs. Bsp KO implants (p < 0.05 by t-test). In panels E and F, color coded volumes indicate densities of 200–400 mg/cm3 HA (red), 400–600 mg/cm3 HA (orange), 600–800 mg/cm3 HA (green), or greater than 800 mg/cm3 HA.

2.3. Altered pyrophosphate metabolism and related gene expression in Bsp knock-out cementoblasts

Based on in vivo mineralization results and complete ablation of the targeted Bsp region in Bsp KO clone 2, this clone was selected for further analysis in vitro. Analysis of proliferation in WT and Bsp KO cells confirmed similar cell growth patterns up to day 6, with some alterations at later days 8–12 (Appendix Figure 1C). Further in vitro experiments described below were performed in the first 6 days of cell culture where no differences were observed in WT and Bsp KO cell numbers.

To further explore potential changes in PPi and Pi metabolism, OCCM.30 parent cementoblasts and Bsp KO clone 2 (hereafter referred to as Bsp KO) cells were analyzed in vitro. Analysis of cell culture media at confluence revealed that Bsp KO cell media contained 50% increased mean PPi concentrations (p < 0.05) and no significant change in Pi concentrations (Figure 3A, B). The Pi/PPi ratio, sometimes used as a surrogate indicator of the favorability for mineralization, was therefore decreased ~50% in Bsp KO vs. WT cementoblasts (33 vs. 58, respectively), a significant difference (p < 0.05) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Altered pyrophosphate metabolism and related gene expression in Bsp knock-out cementoblasts.

(A) Analysis of cell culture media 4 days after confluence reveals 50% significantly increased (p < 0.05 by t-test) PPi concentrations in (n=3) Bsp KO vs. WT OCCM.30 cells. (B) No significant differences are observed in media Pi concentrations in (n=3) Bsp KO vs. WT OCCM.30 cells (p > 0.05 by t-test). (C) Pi/PPi ratio is decreased nearly 50% in (n=3) Bsp KO vs. WT cementoblasts, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05 by t-test). Administration of 2 μg/ml rBSP, mutated rBSP (rBSP-KAE), recombinant OPN (rOPN), or mutated rOPN (rOPN-KAE) was performed with WT and Bsp KO cells, measuring mRNA at 24 hrs after treatment. Altered mRNA expression of (D) Spp1, (E) Ank, (F) Enpp1, and (G) Alpl without and with protein treatments are indicated by different uppercase letters (intragroup differences within WT or KO) or lowercase letters (intergroup differences in WT vs. KO), (p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA).

Compared to WT cementoblasts, Bsp KO cells exhibited the expected significant decrease (p < 0.01) in Bsp mRNA expression to nearly undetectable levels (data not shown). At baseline (DMEM with 2% FBS, 50 μg/ml AA, and 10 mM BGP, with no recombinant proteins added), Bsp KO cells expressed significantly increased Spp1 and Ank mRNA compared to WT, as well as significantly decreased Enpp1 and no change in Alpl (Figure 3D–G). These significant differences in expression of PPi modulating genes in Bsp KO vs. WT cells prompted us to further define signaling effects by treating WT and Bsp KO cells with 2 μg/ml recombinant BSP (rBSP) compared to the same dose of rBSP-KAE, a recombinant protein featuring a knock-in KAE mutation to replace and inactivate the RGD integrin-binding motif implicated in cell signaling [59–61]. For further comparison, cells were also treated in parallel with a related protein, OPN, which also harbors an RGD motif [62]. This protein was added as rOPN or the mutated rOPN-KAE version. Addition of rBSP or rBSP-KAE to WT cells increased Spp1, Ank, and Enpp1 mRNA, with no effect on Alpl (Figure 3D–G). Conversely, addition of rBSP or rBSP-KAE to Bsp KO cells effectively decreased Spp1 and Ank, with no effects on Enpp1 or Alpl. Addition of rOPN or rOPN-KAE to WT cells had no effect on any gene except for Enpp1, which posted small but significant increases. Addition of rOPN or rOPN-KAE to Bsp KO cells had mixed effects, decreasing Spp1 and Ank (as rBSP did), with no effect on Enpp1 or Alpl. Surprisingly, no differences in treatment effects were found between the normal RGD-harboring proteins and mutated KAE proteins, regardless of cell type.

BSP signaling via the RGD domain has been reported to function via integrin induction of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway [59]. Western blot of cellular proteins was employed to determine if rBSP activated MAPK signaling by analysis of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and downstream kinase p90RSK. Addition of 2 μg/ml rBSP yielded no change in phosphorylation state for ERK1/2 or p90RSK between WT or Bsp KO cells over the course of 120 min after treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Recombinant BSP does not affect pP90RSK and pERK levels in cementoblasts.

Western blot of cellular proteins was employed to determine if rBSP activated MAPK signaling by analysis of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and downstream kinase p90RSK in (A) WT or (B) Bsp KO cells. Addition of 2 μg rBSP fails to phosphorylate either ERK1/2 or p90RSK in either cell type over the course of 120 minutes.

2.4. Ablation of Ank incompletely rescues the cementum phenotype in Bsp−/− mice

Ank mRNA was increased in periodontia of Bsp−/− mice (Figure 1E). To directly test in vivo the question of whether reduced cementum in Bsp−/− mice was caused by increased PPi, concentrations, we generated mice lacking both Bsp and Ank. Inactivating mutation or genetic deletion of Ank reduced circulating PPi by more than 50% [46] and reduced in vitro concentrations of extracellular PPi in osteoblasts or fibroblast cultures by 25–50% [19, 23]. Loss of ANK function and the resulting significant decrease in PPi encouraged rapid acellular cementum formation compared to WT mice [6, 7].

Genetic ablation of Ank on the Bsp−/− mouse background proved capable of restoring acellular cementum formation on the molar tooth root (Figure 5A–D and Appendix Figure 2). By 9 dpn, increased acellular cementum deposition was visible in Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice (Figure 5E and Appendix Figure 2A–D). At 26 dpn, double-deficient Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced buccal (cheek side) acellular cementum (47%, p < 0.05) compared to Ank−/− mice (Figure 5F). Likewise, at 60 dpn, Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice featured significantly reduced buccal acellular cementum (31%, p < 0.001) compared to Ank−/− mice (Figure 5G). However, measurements on lingual (tongue side) molar aspects at 26 and 60 dpn did not indicate differences. Because 2D histological measurements did not provide clear and conclusive results, high resolution micro-CT 3D analysis on 60 dpn first mandibular molars (Figure 5H–M) was performed. Bsp−/− mouse acellular cementum could not be analyzed in this fashion due to its severe deficiency, which was well below the working resolution of the micro-CT scanner. Analysis of acellular cementum (segmented to separate it from underlying dentin) confirmed that compared to Ank−/− mice, molars from Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice had a significant 27% reduction in acellular cementum thickness (p < 0.05) and 20% reduction in acellular cementum volume (p < 0.01) (Figure 5N, O). Mean acellular cementum mineral density was increased in Ank−/− mice vs. WT (6%) and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice (4%), though these differences were not significant (Figure 4P). Cellular cementum volume was significantly increased in both Ank−/− (77%) and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− (64%) mice compared to WT (p < 0.001) (Figure 5Q).

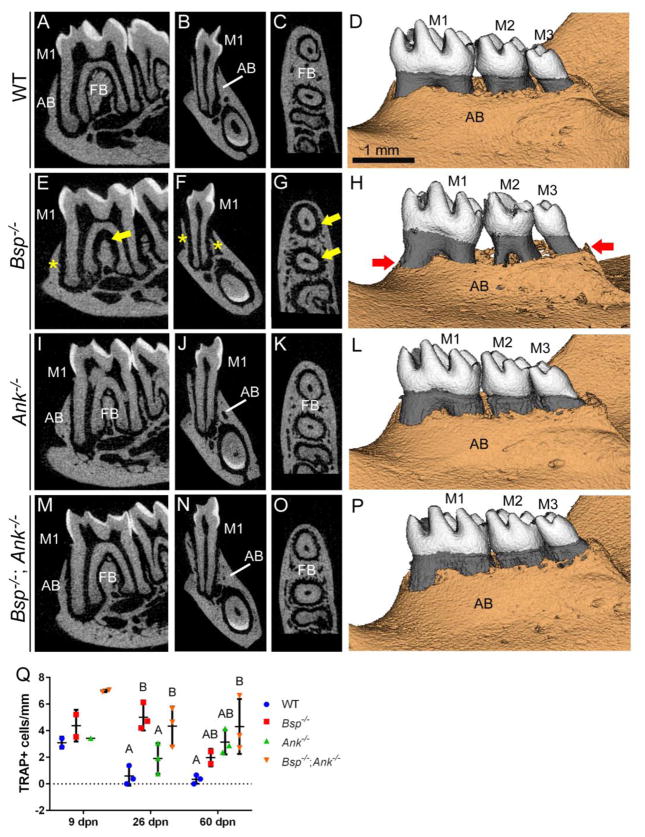

Figure 5. Ablation of Ank incompletely rescues the cementum phenotype in Bsp−/− mice.

Compared to (A) WT buccal side acellular cementum (AC) at 26 dpn, (B) Bsp−/− mice feature reduced AC (red *) and (C) Ank−/− mice feature increased AC. (D) Genetic ablation of Ank on the Bsp−/− mouse background is capable of restoring AC formation on the molar tooth root. Representative histology from 9 and 60 dpn is shown in Appendix Figure 2. Histological measurements of buccal and lingual AC thickness at (E) 9, (F) 26, and (G) 60 dpn reveal significant differences between Ank−/− and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− buccal AC at 26 dpn (* p < 0.05) and 60 dpn (*** p < 0.001), but no differences in lingual AC measurements. High resolution micro-CT analysis of 60 dpn first mandibular first molars was used to segment AC (yellow), as shown in (H–J) 3D surface models and (K–M) 2D cut planes in sagittal, coronal, and transverse sections. Quantitative analyses of AC data from Bsp−/−; Ank−/− vs. Ank−/− mice reveal significantly decreased (N) AC thickness (* p < 0.05) and (O) AC volume (* p < 0.05), (P) but no significant differences between groups in AC mineral density (p > 0.05 by one-way ANOVA). (Q) Both transgenic lines show significantly increased cellular cementum volume compared to WT controls (*** p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA).

Ank−/− mice feature extensive “cementicles,” mineralized nodules extending from the normally smooth cervical cementum surface into PDL space, on the buccal aspect and sometimes extending further into spaces between molars when visualized in 3D by micro-CT (Appendix Figure 3A–C). While Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice featured a 73% reduction in mean cementicle volume vs. Ank−/− mice, this difference did not reach statistical significance due to high variation and small sample sizes (Appendix Figure 3D).

Other parameters were compared by micro-CT analysis in WT, Ank−/−, and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mouse molars. There were no differences between any groups in cellular cementum thickness or density (Appendix Figure 4A, B). No differences in dentin or enamel volumes or densities were noted in Ank−/− or Bsp−/−; Ank−/− vs. WT mice (Appendix Figure 4C–F).

Notably, the periodontal destruction that manifests in Bsp−/− mice was averted in double-deficient mice where PDL attachment was reestablished by restoring a layer of functional acellular cementum (Figure 6A–P) which was significantly thicker than acellular cementum in WT mice. This was not likely due to direct effects on osteoclasts, as numbers of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) positive osteoclast-like cells on alveolar bone surfaces were not different between Bsp−/− and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice at the time points tested (Figure 6Q).

Figure 6. Periodontal function is corrected in Bsp−/−; Ank−/− double-deficient mice.

High resolution micro-CT scanning of (n=3–4) 60 dpn first mandibular first molars (M1) was used to analyze periodontal status of WT, Bsp−/−, Ank−/−, and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice based on appearance of alveolar bone (AB). Compared to (A) sagittal, (B) coronal, and (C) transverse 2D cut planes, and (D) 3D views of the lingual aspect of the mandible from a representative WT mouse, (E–H) Bsp−/− mice exhibit severe loss of AB (yellow * and arrows in 2D images and red arrows in 3D image) and widening of PDL space due to aggressive bone resorption following loss of tooth-PDL attachment. (I–L) Ank−/− mice feature a flared root shape from expanded cementum and periodontal tissues are intact and functional. (M–P) Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice display largely corrected periodontal status compared to Bsp−/− mice, including normal AB in interproximal and furcation regions, and more even PDL-bone borders and AB ridge. (M) Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining and osteoclast-like cell enumeration of (n=3–4) Bsp−/− and Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice at 26 and 60 dpn indicates no differences (p > 0.05 by one-way ANOVA) in osteoclasts/mm. Based on one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test, experimental groups are indicated to not be different from one another by sharing the same capital letter, or to be significantly different (p < 0.05) from one another by being marked with different capital letters.

3. Discussion

Acellular cementum is essential for proper attachment and function of teeth. Bone sialoprotein (BSP) is a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of cementum and has been shown to be essential for acellular cementum growth and function in mice [34, 39, 40]. Here we demonstrate that genetic ablation of Bsp in mice causes perturbations in plasma levels of the mineralization inhibitor, inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), and alters mRNA expression of PPi regulators, Alpl, Spp1, and Ank, within periodontal tissues. Generation of a Bsp knock-out (KO) cementoblast cell line revealed significantly decreased mineralization capacity in these cells, alterations in PPi levels in culture media, and changes in PPi regulators, Spp1 and Ank, that are consistent with changes observed in Bsp−/− mice in vivo. While addition of 2 μg/ml recombinant BSP altered Spp1, Ank, and Enpp1 in WT cementoblasts, gene changes at this dose were not dependent on the RGD integrin-binding domain or MAPK/ERK signaling. Decreasing PPi levels by genetic ablation of Ank on the Bsp−/− mouse background reestablished acellular cementum formation to root surfaces and prevented the periodontal destruction found in between 14 and 26 days post birth in Bsp−/− mice. However, in terms of cementum thickness and volume, reducing PPi below normal levels by ablation of Ank did not fully compensate for the absence of BSP. This novel finding on the antagonistic functions of PPi and BSP provides two important insights. First, though there is a transient perturbation in PPi metabolism in Bsp−/− mice, reversal of this disturbance coincides with lack of complete correction of cementum, supporting a separate role for BSP other than primarily as a driver of PPi. Second, PPi is more potent than BSP as a cementum regulator, as shown by the ability to override loss of BSP by lowering PPi through Ank knock-out Based on these observations, we propose that BSP and PPi work in concert in directing mineralization of cementum and, therefore, possibly other mineralized tissues.

3.1. Intersecting roles of PPi and BSP in mineralization of cementum

Bsp−/− mice feature deficient and defective acellular cementum, resulting in PDL detachment and periodontal breakdown [34, 39, 40]. The demonstrated function of BSP polyE domains to promote hydroxyapatite crystal nucleation and growth [50, 53–57], coupled with the previously established sensitivity of cementum to mineralization disturbances [2, 5–7, 10–16, 24–30], suggested as one hypothesis that BSP may be directly involved in initiation and/or growth of hydroxyapatite mineral in the cementum ECM. The cementum defect in Bsp−/− mice strongly resembles a similar deficiency in the Alpl−/− mouse model of HPP, prompting an alternative hypothesis, that like fellow SIBLING OPN, BSP could be signaling via its RGD motif to affect changes in PPi metabolism. Feedback links between Pi, PPi, and SIBLINGs have been reported previously. Extracellular Pi regulates Spp1/OPN expression in osteoblast and cementoblasts [63–66], while PPi also increases Spp1/OPN in osteoblasts [22, 52], in part through MAPK signaling. Administration of Pi was also reported to affect Bsp, dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1), and numerous other genes in cementoblasts [66, 67]. An expanded role for Pi signaling in dental and skeletal mineralization has been further suggested by recent work showing that Pi induced formation and influenced protein composition of matrix vesicles in odontoblasts and osteoblasts [68]. Enpp1 has been linked to differentiation in osteoblasts, including association of RUNX2 with the Bsp promoter [69]. In addition to its role in decreasing PPi, TNAP was also shown to dephosphorylate OPN, rendering it less able to inhibit mineralization [51].

We previously found elevated ALP in Bsp−/− mice during development [34, 40]. In the present study, we found further evidence that BSP is involved in regulating expression of PPi-associated genes. First, circulating levels of PPi showed disruptions in Bsp−/− mice at some ages. Second, local expression of Alpl, Spp1, and Ank were disrupted in periodontal tissues. Third, PPi levels and gene regulators were similarly disrupted in Bsp KO cementoblasts, in vitro. Fourth, addition of recombinant BSP (rBSP) affected gene levels of PPi regulators in both control and Bsp KO cementoblasts. Despite these affirmative findings, two important observations generated in this study argue against PPi being the primary driver for cementum pathology. First, in vivo alterations in Alpl, Spp1, and Ank were not found by 14 dpn, a time point when acellular cementum is already significantly decreased in in Bsp−/− mice [34]. Second, reduction in PPi through Ank ablation allowed reestablishment of cementum formation in mice, but with a sustained and significant deficit in cementum thickness and volume in the absence of BSP (compared to Ank−/− controls). These findings support a model where PPi and BSP may work in concert directing cementogenesis. While we draw the conclusion that PPi is not directly responsible for all cementum defects in Bsp−/− mice, the observed disturbances in PPi metabolism cannot be wholly ruled out as contributing to phenotypic changes in dentoalveolar and skeletal tissues, such as hypomineralization of alveolar and long bones.

Could BSP be affecting cementum and other tissues by alternative signaling mechanisms? Use of QPCR array identified alterations in tooth and bone-associated transcription factors (Runx2, Sp7). The potential role of Runx2 in cementogenesis remains unclear [70], while Sp7/osterix was shown to be involved in cellular cementum formation, but knock-out or over-expression had no measureable effect on acellular cementum formation [71]. Phospho1 mRNA was significantly down-regulated in Bsp−/− mouse periodontia at 26 dpn. PHOSPHO1 is a phosphatase indicated to be important in matrix vesicle initiated mineralization of bone and mantle dentin [72–77]. In recent studies on periodontal development in Phospho1−/− mice, we found that while alveolar bone and cellular cementum displayed mineralization defects, acellular cementum development appeared unperturbed and no periodontal dysfunction was evident up to 3 months of age [78]. The implications of down-regulated Phospho1 mRNA remain unclear, though it is intriguing that loss of BSP causes increased expression of Alpl, a critical positive regulator of acellular cementum formation [6, 15, 79].

QPCR array identified numerous alterations in genes associated with Wnt and TGFβ signaling pathways (Ctnnb1, Lrp6, Dkk1 and Smad4, Bgn, respectively) in Bsp−/− vs. WT periodontal tissues. These changes are intriguing, especially because Wnt and TGFβ signaling have both been implicated in cementogenesis [80–84]. However, like the changes in PPi-associated genes, these were not identified until 26 dpn, after the primary cementum defect in Bsp−/− had been evident for some time. In fact, by this age, Bsp−/− mice exhibit PDL detachment and disorganization, junctional epithelium down growth, alveolar bone resorption, and beginnings of periodontal breakdown [34]. It is entirely possible that these transcriptional changes are in response to periodontal tissue changes rather than the cause of changes- a feedback loop reflecting tissue damage or attempts at healing.

Additional in vivo and in vitro findings can be considered in this context. Addition of 2 μg/ml of rBSP to OCCM.30 cementoblasts altered gene expression of target genes, however signaling resulting from this dose did not appear to be through RGD-integrin binding (due to lack of phosphorylation of ERK and P90RSK), as has been demonstrated previously in osteoblasts [85]. In this context and at the dose used, the MAPK signaling pathway was not implicated in BSP signaling. Previous studies have also indicated that BSP can influence cell attachment and migration through RGD-independent mechanisms [86, 87].

3.2. Evolving roles of SIBLING proteins in cementogenesis

The SIBLING family comprises ECM phosphoproteins associated with mineralized tissues of the skeleton and dentition, including BSP, OPN, dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1), dentin sialoprotein (DSP), dentin phosphoprotein (DPP), and matrix extracellular phosphoprotein (MEPE) [31–33]. DMP1, DSP, and DPP are important for dentinogenesis [88, 89], and DMP1 was also shown to regulate mineral metabolism via fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)-mediated effects on Pi handling [90–92]. Loss of either Dspp or Dmp1 in mice causes changes in acellular cementum, however it remains unclear if this is due to a direct role of the associated proteins in cementogenesis, or indirect effects of wider changes in the periodontium or mineral metabolism [26, 93–95]. While MEPE has been shown to regulate skeletal mineralization, its role in dental development has only been recently investigated, implicating the protein in dentinogenesis and amelogenesis, whereas its role in cementum formation remains undefined [96].

BSP and OPN have long served as markers for cementoblasts and cementum [35–37, 97–99], and the potential link between BSP and related protein OPN deserves special mention. OPN has been shown to have direct inhibitory effects on mineralization via the negative charges from its many phosphorylated serine residues [50, 100–102]. OPN also exerts indirect effects on mineralization by regulating PPi metabolism through expression of Ank/ANK, Enpp1/ENPP1, and Alpl/TNAP [46, 47], and has been implicated in cell migration, attachment, and signaling through its RGD domain [103–108]. Loss of BSP increased Spp1/OPN in the periodontium and addition of rOPN affected expression of Ank in Bsp KO cells and Enpp1 in WT cementoblasts, in vitro. The potential role of OPN in directly inhibiting cementum mineralization, or itself regulating PPi-associated genes, is worth considering but difficult to evaluate in the context of Bsp−/− mice. Expression of Spp1 did not increase until 26 dpn, though OPN protein was present on root surfaces at earlier ages. Crossing of Bsp−/− and Spp1−/− mice to create double-deficient mice is not possible due to the close proximity of these genes on mouse chromosome 5 [33]. Therefore, we are currently evaluating tooth development in Spp1−/− mice, where we will also genetically alter PPi by creating Spp1−/−; Alpl−/− and Spp1−/−; Ank−/− mice to test for OPN functions in periodontal tissues in normal, high, and low PPi conditions (manuscript submitted). Potential interactions, compensations, or antagonistic functions of BSP and OPN may be addressed by other approaches in the future.

3.3. Conclusions

The Bsp KO cementoblasts created in this study appear to recapitulate effects of developmental Bsp ablation in mice, namely, significantly reduced capacity for mineralization similar to defects and delays in cementum and bone [34, 39, 40]. Here we have analyzed one of these clones (Bsp KO clone 2) in depth in terms of gene expression and response to rBSP and rOPN. In ongoing work following on the QPCR gene expression changes noted in vivo, the Bsp KO cementoblast lines will serve as valuable tools to identify alternative mechanisms for BSP signaling, such as by identifying transcriptomic changes by RNA sequencing. This approach will enable further studies on the potential feedback loop between BSP and PPi-associated and other factors. The possibility that BSP is directly modulating cementum mineralization is also part of an ongoing study that will employ in vivo and in vitro transgenic approaches.

While the data generated here demonstrate overlapping roles for BSP and classic PPi regulators in guiding cementum formation, and add new insights to the previous literature on links between Pi, PPi, and SIBLING proteins, several limitations and unanswered questions remain. These include not yet identifying a specific signaling mechanism for BSP on cementoblasts, use of a single Bsp KO clone for in vitro signaling studies, and limitations inherent in cell culture approaches for understanding complex developmental processes. Additional studies are warranted to confirm whether feedback between BSP and PPi regulators are direct, indirect, or coincidental, and identify more precisely the functions(s) of BSP in dental and skeletal development. Continued studies targeting the functional domains of BSP or conditionally ablating Bsp in tissue or time-specific fashion are anticipated to elucidate the mechanism(s) underlying the BSP-PPi link and the importance of BSP in cementogenesis.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC), National Institutes of Health (NIH; Bethesda, MD, USA). Preparation and genotyping of Bsp knock-out (Bsp−/−) and Ank−/− mice were described previously [6, 34, 109]. Mice were maintained on a mixed 129/CD1 background. Heterozygote breeding pairs were employed to prepare homozygous Bsp−/− and Ank−/− mice, and double heterozygotes were used to generate mice ablated for both Ank and Bsp (Bsp−/−; Ank−/− mice), and littermate wild-type (WT) controls. After weaning, mice were provided a soft gel diet (Diet Gel 31M, Clear H2O, Portland, ME, USA) to reduce incisor malocclusion noted in homozygous Bsp−/− mice. Mandibles were harvested for analysis at ages 5, 9, 14, 26, and 60 days postnatal (dpn) with n=3–9 mice per genotype, unless otherwise noted.

4.2. In vivo gene expression analyses

For quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) array analysis of periodontia from Bsp−/− and WT mice (5, 14, and 26 dpn, n=3 per genotype), first molars were removed from mandibles using 15c scalpel blades under a dissecting microscope. Full thickness mucoperiosteal flap was reflected to permit visualization of bone. Alveolar bone was removed to expose periodontal ligament (PDL) surrounding the root surface. Collected PDL samples were stored in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted from the PDL using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and cDNA was synthesized by RT2 PreAMP cDNA Synthesis Kit (Qiagen). Samples were analyzed for expression of 84 genes involved in differentiation, ECM, adhesion, and mineralization using a designer PCR array platform (#CAMP12364F) from SABioscience/Qiagen. Target gene expression was normalized to 5 housekeeping genes, and positive and negative PCR controls were included in each PCR plate. PCR array reactions were performed on the LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) following manufacturer’s recommendations. Analysis of fold-changes in gene expression was performed as described previously [39], using RT2 Profiler PCR array web portal (http://pcrdataanalysis.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php).

4.3. Blood biochemistry and assays

Mice (n=4–8 per genotype) were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine and blood was collected in lithium heparin gel tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) by cardiac puncture. Plasma were separated by centrifugation at G-force for 10 min at room temperature, aliquoted and were stored at −80°C. Measurement of plasma pyrophosphate (PPi) concentration followed the protocol described previously [110, 111]. In brief, plasma were heated at 65°C for 10 min, then 10 μl of plasma (in triplicate) were diluted 4 times with autoclaved distilled water and each sample was prepared in triplicate. Samples were assayed for PPi by differential absorption on activated charcoal of UDP-D-[6- 3H] glucose (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA) by measuring the radioactivity in Ecolume (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) [112]. Measurement of plasma OPN concentration employed a mouse/rat specific osteopontin ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) that was used according to manufacturer’s instructions.

4.4. Targeted knock-out of Bsp in cementoblasts

OCCM.30 immortalized murine cementoblasts have been well-characterized for their gene expression profile and ability to promote mineralization in vitro and in vivo [6, 58]. Genetic deletion of Bsp in OCCM.30 cells was achieved using CRISPR/Cas9 system (Applied StemCell, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The deletion region was designed to cover 8 bp on exon 1, and the entirety of exons 2 (51 bp) and 3 (78 bp), generating a frame-shift deletion by precise end joining (Figure 2A). OCCM.30 parent cells displayed 50–70% transfection efficiency and were transfected with a dual gRNA vector containing mIbsp.g17 and mIbsp.g33, known to exhibit a low off-target profile. After puromycin (5 μg/ml) selection, paternal and maternal alleles were separated using TOPO vector cloning. Five independent Bsp knock-out (KO) clones were identified and confirmed by sequencing.

4.5. In vivo ossicle implant model

An ossicle implant model was employed to assay the effect of Bsp ablation on the ability of OCCM.30 cells to promote mineral nodule formation, in vivo. Parent OCCM.30 (WT) cells and n=5 Bsp KO clones were used. Procedures for seeding and implantation have been reported previously [113, 114]. In brief, collagen-elastin sponges (Zimmer, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were cut into 5 × 5 × 5 mm blocks and incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; 4.5 g/L glucose, L-glutamine, 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate, with phenol red dye; 11995-065, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) media for 30 min. Media were removed and 2×106 cells (WT or Bsp KO) were suspended in 15 μl DMEM, seeded into each collagen block, and implanted into subcutaneous pouches along the back of SCID Hairless Congenic (SHCTM) mice (n=3 per cell genotype). Control implants included cell-free collagen sponges. Implants were retrieved at 8 wks and fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

4.6. Histology

Tissues were fixed in Bouin’s solution and demineralized in AFS (acetic acid, formaldehyde, sodium chloride), as previously described [35]. Mandibles were processed and embedded for paraffin serial sectioning to collect coronal (buccal-lingual) sections of 5 μm in thickness. Fixed ossicle implants were demineralized in 10% neutral buffered formalin and hemisected for paraffin serial sectioning in 5 μm as well. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed for morphological observations and histomorphometry.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as described previously [34] using an avidin-biotinylated peroxidase (ABC) based kit (Vectastain Elite, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) with a 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate to produce a red-brown product. Primary antibody included rabbit polyclonal LF-175 rabbit anti-mouse osteopontin (OPN), which was used at 1:200 dilution with no antigen retrieval [35]. Secondary antibody (included in the ABC kit) was goat anti-rabbit IgG. Negative controls included slides processed through the same protocol except lacking primary antibody addition.

4.7. Histomorphometry

Static histomorphometry was used to measure acellular cementum thickness in coronal sections at 9, 26, and 60 dpn (n=3–9 per genotype, unless otherwise noted). From serial sections, central sections of the mesial root of the first mandibular molar were used for measurement. Leica digital imaging hub (version 4.0.9; Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) or imageJ (version 1.51k; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to make calibrated measurements. Measurements of acellular cementum were made at fixed distances of 100 μm from the cementum-enamel junction (CEJ) for 14 dpn tissues and 400 μm from CEJ for 26 and 60 dpn tissues, on both buccal and lingual aspects of the tooth root.

4.8. Radiography and microcomputed tomography (micro-CT)

Implants were scanned in a cabinet x-ray (Faxitron Bioptics, LLC, Tucson, AZ, USA) at 30 kV for 40 sec for qualitative analysis, and scanned for quantitative analysis in a μCT 50 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) at 70 kVp, 76 μA, 0.5 Al Filter, 300 ms integration time, and 10 μm voxel size. DICOM images were uploaded to AnalyzePro 1.0 (AnalyzeDirect, Overland Park, KS, USA) and calibrated to a standard curve of 5 hydroxyapatite (HA) standards of known densities (mg HA/cm3). Implants where segmented into 4 density groups: 200–400, 400–600, 600–800, and greater than 800 mg/cm3 HA. These were analyzed for average volume and density as a group and individually. Fixed hemi-mandibles from 60 dpn mice were scanned in 70% ethanol on μCT 50 using the same parameters described above, except for 2 μm voxel size. DICOM images were uploaded to AnalyzePro 1.0 (AnalyzeDirect) and oriented to show 3D surface views or 2D cut planes. Dentin was segmented at 650 mg/cm3 HA, and enamel was segmented at 1600 mg/cm3 HA. For segmentation of cementum, a median filter with a kernel size of 11 was employed. Cementum was segmented between 400–950 mg/cm3 HA with manual corrections to exclude predentin and less dense dentin in regions away from dentin borders. The median filter tracing layer was used as a mask and final segmentation of the cementum was defined as above 650 mg/cm3 HA on the original object. For volume analysis, each root (mesial and distal) was divided into thirds based on the total length measured from cementum-enamel junction (CEJ) to the most apical tip. The most cervical 2/3 of the root length was defined as acellular cementum and the most apical 1/3 of the root length was defined as cellular cementum. This ratio was guided by previous histological reports as well as pilot studies comparing cementum histology to micro-CT images, using landmarks including cementocyte lacunae and the expanded contour of cellular cementum on root surfaces. To measure acellular cementum thickness, 50 slices (100 μm) were selected 1/3 of the CEJ-apex distance. To measure cellular cementum thickness, 50 slices (100 μm) were selected 100 μm from the root apex. These regions were chosen for being well within the borders of the respective acellular and cellular cementum layers, with consistent landmarks used between samples. Thickness was determined using cortical thickness algorithms.

4.9. Cell culture

WT and Bsp KO OCCM.30 cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all reagents from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For in vitro gene expression experiments, cells (8×104 cells/well, 12-well tissue culture treated plate) were seeded in standard media as described above. After 24 hrs, media were changed to DMEM with 2% v/v FBS and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (AA). At confluence (day 0), media were changed to include 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (BGP) for the remainder of the experiment.

4.10. Cell proliferation assay

For proliferation experiments, 1 × 104 cells/ml were plated in DMEM with 10% v/v FBS, antibiotics, and L-glutamine. After 24 hrs, media were changed to DMEM with 2% v/v FBS and antibiotics and L-glutamine for the remainder of the experiment, and media were changed every 2–3 days. Cell proliferation was analyzed using an MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt] based colorimetric assay, following manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a 96-well plate reader.

4.11. Inorganic phosphate and pyrophosphate analysis, in vitro

For inorganic phosphate (Pi) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) assays, cells were plated as described above until they reached confluence. Media were removed, and cells were rinsed with Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and plated in Opti-MEM (approximately 1.05 mM sodium phosphate monobasic) without added FBS, antibiotics, or L-glutamine, for 24 hrs before collection of media for analysis. Phosphate assay colorimetric kit (ab65622) and pyrophosphate assay fluorometric kit (ab112155) were used to measure Pi and PPi concentrations, respectively, in culture media following manufacturer’s directions (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Absorbance for Pi was recorded at 650 nm and fluorescence for PPi was measured at excitation/emission of 316/456 nm using a 96-well plate reader. Concentrations were calculated using standard curves (r>0.98).

4.12. Addition of recombinant proteins, in vitro

Experiments were performed with or without addition of recombinant BSP or OPN proteins (rBSP, rOPN), or with rBSP-KAE or rOPN-KAE (RGD integrin-binding sequence mutated to KAE). Recombinant proteins were purified from conditioned media of human bone marrow stromal cells infected with adenoviruses, as described previously [115, 116]. Doses for recombinant BSP proteins were based on dose ranges used in previous reports [87, 115, 117] and included 0.02, 0.2, and 2 μg/ml rBSP, where all doses showed biological activity on expression of target genes (data not shown). Experiments with rBSP, rBSP-KAE, rOPN, and rOPN-KAE were performed with a dose of 2 μg/ml recombinant protein for all treatments. Recombinant proteins were added for 24 hrs prior to RNA isolation.

4.13. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Isolation of total RNA, synthesis of cDNA, and performance of QPCR was performed as previously described [39]. PCR primers used included: Alpl (NM_007431.3): F-GGGGACATGCAGTATGAGTT and R-GGCCTGGTAGTTGTTGTGAG; Spp1 (NM_001204201.1): F-TTTACAGCCTGCACCC and R-CTAGCAGTGACGGTCT; Ank (NM_020332): F-GAATCAGTCGGCCCAT and R-GTTCGCCAGTTTATTGCT; Enpp1 (NM_001308327): F- CGCCACCGAGACTAAA and R- TCATAGCGTCCGTCAT; Gapdh (NM_001289726): F- ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC and R- TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA.

4.14. Western blot analysis

For cellular protein analysis by Western blot, WT and Bsp KO cells were treated with rBSP for up to 120 min. Total cellular proteins were extracted from washed cells using M-PER mammalian protein extraction kit (#78501, Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. EDTA-free Halt™ protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific) was included to prevent protein degradation during the extraction process. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford colorimetric assay (Thermo Scientific). 20 μg of total protein was used for SDS-PAGE in a 4% to 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA), then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. An antibody cocktail targeted to the AKT/MAPK signaling pathway, including rabbit anti-mouse/human ERK1/2 and p-P90RSK, was used according to manufacturer directions (ab151279, Abcam, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:250. IRDye secondary antibodies (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) were used. Detection was performed using a digital imaging system (ODYSSEY CLx-LI-COR).

4.15. Statistical analysis

Results for histomorphometry, in vivo ossicle assay, in vitro assays, and micro-CT analyses are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using Student’s (independent samples) t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons, where p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were computed using GraphPad Prism 6.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Bone sialoprotein knockout (Bsp−/−) mice feature a 2-fold increase in circulating pyrophosphate (PPi) and altered mRNA expression of PPi regulators Alpl, Spp1, and Ank in the periodontia

Bsp knock-out cementoblasts exhibit significantly decreased mineralization capacity and increased PPi in culture media

Addition of recombinant BSP altered Spp1, Ank, and Enpp1 mRNA expression in cementoblasts, in vitro

Decreasing PPi by genetic ablation of Ank on the Bsp−/− mouse background reestablished cementum formation but did not fully compensate for the absence of BSP

Perturbations in PPi metabolism are not solely driving the cementum pathology in Bsp−/− mice and PPi is more potent than BSP as a cementum regulator

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AR 066110 to BLF from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD), the Intramural Research Program of NIAMS (MJS), and grant DE 12889 to JLM from the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR)/NIH. We thank Kristina Zaal (Light Imaging Section, NIAMS/NIH) for assistance in slide scanning.

Abbreviations

- SIBLING

Small Integrin-Binding Ligand N-linked Glycoprotein

- BSP

bone sialoprotein

- OPN

Osteopontin

- TNAP

tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase

- PPi

inorganic pyrophosphate

- ANK

progressive ankylosis protein

- ENPP1

ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1

- KO

knock-out

- PDL

periodontal ligament

- HPP

hypophosphatasia

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- RGD

arginine-glycine-aspartic acid

- Poly-E

polyglutamic acid

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Foster BL, Nociti FH, Jr, Somerman MJ. Tooth Root Formation. In: Huang GTJ, Thesleff I, editors. Stem Cells, Craniofacial Development and Regeneration. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster BL, et al. Rare Bone Diseases and Their Dental, Oral, and Craniofacial Manifestations. J Dent Res. 2014;93(7 suppl):7S–19S. doi: 10.1177/0022034514529150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster BL, Nociti FH, Jr, Somerman MJ. The rachitic tooth. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(1):1–34. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosshardt D. Are cementoblasts a subpopulation of osteoblasts or a unique phenotype? J Dent Res. 2005;84(5):390–406. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster BL, et al. The progressive ankylosis protein regulates cementum apposition and extracellular matrix composition. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;194(5):382–405. doi: 10.1159/000323457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster BL, et al. Central role of pyrophosphate in acellular cementum formation. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nociti FH, Jr, et al. Cementum: a phosphate-sensitive tissue. J Dent Res. 2002;81(12):817–21. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millan JL, Whyte MP. Alkaline Phosphatase and Hypophosphatasia. Calcif Tissue Int. 2016;98(4):398–416. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-0079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruckner R, Rickles N, Porter D. Hypophosphatasia with premature shedding of teeth and aplasia of cementum. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962;15:1351–69. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster BL, et al. Tooth root dentin mineralization defects in a mouse model of hypophosphatasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(2):271–82. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zweifler LE, et al. Counter-regulatory phosphatases TNAP and NPP1 temporally regulate tooth root cementogenesis. Int J Oral Sci. 2015;7(1):27–41. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2014.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKee MD, et al. Enzyme Replacement Therapy Prevents Dental Defects in a Model of Hypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2011;90(4):470–476. doi: 10.1177/0022034510393517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beertsen W, VandenBos T, Everts V. Root development in mice lacking functional tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase gene: inhibition of acellular cementum formation. J Dent Res. 1999;78(6):1221–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Bos T, et al. Cementum and dentin in hypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2005;84(11):1021–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster BL, et al. Conditional Alpl Ablation Phenocopies Dental Defects of Hypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2017;96(1):81–91. doi: 10.1177/0022034516663633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadav MC, et al. Enzyme replacement prevents enamel defects in hypophosphatasia mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(8):1722–34. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurley K, et al. Mineral formation in joints caused by complete or joint-specific loss of ANK function. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(8):1238–47. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurley K, Reimer R, Kingsley D. Biochemical and genetic analysis of ANK in arthritis and bone disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(6):1017–29. doi: 10.1086/509881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho A, Johnson M, Kingsley D. Role of the mouse ank gene in control of tissue calcification and arthritis. Science. 2000;289(5477):265–70. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terkeltaub R, et al. Causal link between nucleotide pyrophosphohydrolase overactivity and increased intracellular inorganic pyrophosphate generation demonstrated by transfection of cultured fibroblasts and osteoblasts with plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1. Relevance to calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(6):934–41. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson K, et al. Matrix vesicle plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 regulates mineralization by murine osteoblastic MC3T3 cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(6):883–92. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harmey D, et al. Concerted regulation of inorganic pyrophosphate and osteopontin by akp2, enpp1, and ank: an integrated model of the pathogenesis of mineralization disorders. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(4):1199–209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson K, et al. Linked deficiencies in extracellular PP(i) and osteopontin mediate pathologic calcification associated with defective PC-1 and ANK expression. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(6):994–1004. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biosse Duplan M, et al. Phosphate and Vitamin D Prevent Periodontitis in X-Linked Hypophosphatemia. J Dent Res. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0022034516677528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fong H, et al. Aberrant cementum phenotype associated with the hypophosphatemic hyp mouse. J Periodontol. 2009;80(8):1348–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye L, et al. Periodontal breakdown in the Dmp1 null mouse model of hypophosphatemic rickets. J Dent Res. 2008;87(7):624–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaipatur N, Murshed M, McKee M. Matrix Gla protein inhibition of tooth mineralization. J Dent Res. 2008;87(9):839–44. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alatli I, Hammarström L. Root surface defects in rat molar induced by 1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate. Acta Odontol Scand. 1996;54(1):59–65. doi: 10.3109/00016359609003511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alatli-Kut I, Hultenby K, Hammarström L. Disturbances of cementum formation induced by single injection of 1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate (HEBP) in rats: light and scanning electron microscopic studies. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102(5):260–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1994.tb01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beertsen W, Niehof A, Everts V. Effects of 1-hydroxyethylidene-1, 1-bisphosphonate (HEBP) on the formation of dentin and the periodontal attachment apparatus in the mouse. Am J Anat. 1985;174(1):83–103. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001740107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Six genes expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the SIBLING family of proteins. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staines KA, MacRae VE, Farquharson C. The importance of the SIBLING family of proteins on skeletal mineralisation and bone remodelling. J Endocrinol. 2012;214(3):241–55. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher LW, et al. Flexible structures of SIBLING proteins, bone sialoprotein, and osteopontin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280(2):460–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster BL, et al. Deficiency in acellular cementum and periodontal attachment in bsp null mice. J Dent Res. 2013;92(2):166–72. doi: 10.1177/0022034512469026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster BL. Methods for studying tooth root cementum by light microscopy. Int J Oral Sci. 2012;4(3):119–28. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKee M, Zalzal S, Nanci A. Extracellular matrix in tooth cementum and mantle dentin: localization of osteopontin and other noncollagenous proteins, plasma proteins, and glycoconjugates by electron microscopy. Anat Rec. 1996;245(2):293–312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199606)245:2<293::AID-AR13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macneil R, et al. Bone sialoprotein is localized to the root surface during cementogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9(10):1597–606. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somerman M, et al. Expression of attachment proteins during cementogenesis. J Biol Buccale. 1990;18(3):207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster BL, et al. Mineralization defects in cementum and craniofacial bone from loss of bone sialoprotein. Bone. 2015;78:150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soenjaya Y, et al. Mechanical Forces Exacerbate Periodontal Defects in Bsp-null Mice. J Dent Res. 2015;94(9):1276–85. doi: 10.1177/0022034515592581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg HA, Hunter GK. Functional Domains of Bone Sialoprotein. In: Goldberg M, editor. Phosphorylated Extracellular Matrix Proteins of Bone and Dentin. Bentham Science Publishers; 2012. pp. 266–282. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain A, et al. Structural requirements for bone sialoprotein binding and modulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Biochemistry. 2008;47(38):10162–70. doi: 10.1021/bi801068p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qin C, Baba O, Butler W. Post-translational modifications of sibling proteins and their roles in osteogenesis and dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15(3):126–36. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salih E, Zhou HY, Glimcher MJ. Phosphorylation of purified bovine bone sialoprotein and osteopontin by protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(28):16897–905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baht GS, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser136 is critical for potent bone sialoprotein-mediated nucleation of hydroxyapatite crystals. Biochem J. 2010;428(3):385–95. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harmey D, et al. Elevated skeletal osteopontin levels contribute to the hypophosphatasia phenotype in Akp2(−/−) mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(9):1377–86. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harmey D, et al. Concerted regulation of inorganic pyrophosphate and osteopontin by akp2, enpp1, and ank: an integrated model of the pathogenesis of mineralization disorders. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(4):1199–209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holm E, et al. Osteopontin mediates mineralization and not osteogenic cell development in vitro. Biochem J. 2014;464(3):355–64. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pampena DA, et al. Inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by osteopontin phosphopeptides. Biochem J. 2004;378(Pt 3):1083–7. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunter GK, et al. Nucleation and inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by mineralized tissue proteins. Biochem J. 1996;317(Pt 1):59–64. doi: 10.1042/bj3170059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narisawa S, Yadav MC, Millan JL. In vivo overexpression of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase increases skeletal mineralization and affects the phosphorylation status of osteopontin. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(7):1587–98. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Addison W, et al. Pyrophosphate inhibits mineralization of osteoblast cultures by binding to mineral, up-regulating osteopontin, and inhibiting alkaline phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(21):15872–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tye CE, et al. Delineation of the hydroxyapatite-nucleating domains of bone sialoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):7949–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris N, et al. Functional analysis of bone sialoprotein: identification of the hydroxyapatite-nucleating and cell-binding domains by recombinant peptide expression and site-directed mutagenesis. Bone. 2000;27(6):795–802. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldberg HA, et al. Determination of the hydroxyapatite-nucleating region of bone sialoprotein. Connect Tissue Res. 1996;35(1–4):385–92. doi: 10.3109/03008209609029216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Modulation of crystal formation by bone phosphoproteins: role of glutamic acid-rich sequences in the nucleation of hydroxyapatite by bone sialoprotein. Biochem J. 1994;302(Pt 1):175–9. doi: 10.1042/bj3020175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Nucleation of hydroxyapatite by bone sialoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(18):8562–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D’Errico JA, et al. Employing a transgenic animal model to obtain cementoblasts in vitro. J Periodontol. 2000;71(1):63–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gordon JA, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by bone sialoprotein regulates osteoblast differentiation. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189(1–4):138–43. doi: 10.1159/000151728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon JA, et al. Bone sialoprotein stimulates focal adhesion-related signaling pathways: role in migration and survival of breast and prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107(6):1118–28. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganss B, Kim R, Sodek J. Bone sialoprotein. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10(1):79–98. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oldberg A, Franzen A, Heinegard D. Cloning and sequence analysis of rat bone sialoprotein (osteopontin) cDNA reveals an Arg-Gly-Asp cell-binding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(23):8819–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beck GR, Zerler B, Moran E. Phosphate is a specific signal for induction of osteopontin gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(15):8352–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140021997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beck GR, Knecht N. Osteopontin regulation by inorganic phosphate is ERK1/2-, protein kinase C-, and proteasome-dependent. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(43):41921–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fatherazi S, et al. Phosphate regulates osteopontin gene transcription. J Dent Res. 2009;88(1):39–44. doi: 10.1177/0022034508328072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foster B, et al. Regulation of cementoblast gene expression by inorganic phosphate in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78(2):103–12. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rutherford R, et al. Extracellular phosphate alters cementoblast gene expression. J Dent Res. 2006;85(6):505–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaudhary SC, et al. Phosphate induces formation of matrix vesicles during odontoblast-initiated mineralization in vitro. Matrix Biol. 2016;52–54:284–300. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nam HK, et al. Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase-1 (ENPP1) protein regulates osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(45):39059–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zou S, et al. Tooth eruption and cementum formation in the Runx2/Cbfa1 heterozygous mouse. Arch Oral Biol. 2003;48(9):673–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(03)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao Z, et al. Genetic evidence for the vital function of Osterix in cementogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5):1080–92. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huesa C, et al. The Functional co-operativity of Tissue-Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase (TNAP) and PHOSPHO1 during initiation of Skeletal Mineralization. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2015;4:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKee MD, et al. Compounded PHOSPHO1/ALPL deficiencies reduce dentin mineralization. J Dent Res. 2013;92(8):721–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Millan JL. The role of phosphatases in the initiation of skeletal mineralization. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93(4):299–306. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9672-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yadav MC, et al. Loss of skeletal mineralization by the simultaneous ablation of PHOSPHO1 and alkaline phosphatase function: A unified model of the mechanisms of initiation of skeletal calcification. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(2):286–97. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Macrae V, et al. Inhibition of PHOSPHO1 activity results in impaired skeletal mineralization during limb development of the chick. Bone. 2010;46(4):1146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roberts S, et al. Functional involvement of PHOSPHO1 in matrix vesicle-mediated skeletal mineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(4):617–27. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zweifler LE, et al. Role of PHOSPHO1 in Periodontal Development and Function. J Dent Res. 2016;95(7):742–51. doi: 10.1177/0022034516640246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Foster BL, et al. Periodontal Defects in the A116T Knock-in Murine Model of Odontohypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):706–14. doi: 10.1177/0022034515573273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cao Z, et al. Osterix controls cementoblast differentiation through downregulation of Wnt-signaling via enhancing DKK1 expression. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11(3):335–44. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.10874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim TH, et al. Constitutive stabilization of β-catenin in the dental mesenchyme leads to excessive dentin and cementum formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412(4):549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bae CH, et al. Excessive Wnt/beta-catenin signaling disturbs tooth-root formation. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48(4):405–10. doi: 10.1111/jre.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao J, Symons A, Bartold P. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta1) in the developing periodontium of rats. J Dent Res. 1998;77(9):1708–16. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770090701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ripamonti U. Recapitulating development: a template for periodontal tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(1):51–71. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gordon JA, et al. Bone sialoprotein expression enhances osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization in vitro. Bone. 2007;41(3):462–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stubbs JT, et al. Characterization of native and recombinant bone sialoprotein: delineation of the mineral-binding and cell adhesion domains and structural analysis of the RGD domain. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(8):1210–22. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Karadag A, et al. Bone sialoprotein, matrix metalloproteinase 2, and alpha(v)beta3 integrin in osteotropic cancer cell invasion. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(12):956–65. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sreenath T, et al. Dentin sialophosphoprotein knockout mouse teeth display widened predentin zone and develop defective dentin mineralization similar to human dentinogenesis imperfecta type III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(27):24874–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y, et al. Rescue of odontogenesis in Dmp1-deficient mice by targeted re-expression of DMP1 reveals roles for DMP1 in early odontogenesis and dentin apposition in vivo. Dev Biol. 2007;303(1):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu S, et al. Pathogenic role of Fgf23 in Dmp1-null mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(2):E254–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90201.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lorenz-Depiereux B, et al. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2006;38(11):1248–50. doi: 10.1038/ng1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Feng J, et al. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet. 2006;38(11):1310–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gibson MP, et al. Failure to process dentin sialophosphoprotein into fragments leads to periodontal defects in mice. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121(6):545–50. doi: 10.1111/eos.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gibson MP, et al. Loss of dentin sialophosphoprotein leads to periodontal diseases in mice. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48(2):221–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen Y, et al. DSPP Is Essential for Normal Development of the Dental-Craniofacial Complex. J Dent Res. 2016;95(3):302–10. doi: 10.1177/0022034515610768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gullard A, et al. MEPE Localization in the Craniofacial Complex and Function in Tooth Dentin Formation. J Histochem Cytochem. 2016;64(4):224–36. doi: 10.1369/0022155416635569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]