Abstract

Background

Pancreatic schwannoma is a rare tumor. Preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic schwannoma is challenging due to its tendency to mimic other lesions of the pancreas. We describe a case of pancreatic schwannoma and present a review of the cases currently reported in the English literature to identify characteristics of pancreatic schwannoma on imaging.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old male presented with a history of intermittent periumbilical abdominal pain and lower back pain for 1 week. Based on ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) findings, we made a preoperative diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumor and performed a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Pathological examination showed that the tumor was composed of spindle cells with a palisading arrangement, and immunohistochemistry revealed strong positive staining for S-100 protein, which was consistent with a diagnosis of pancreatic schwannoma. At the 8-month follow-up visit, the patient was doing well without recurrent disease, and his abdominal pain had resolved.

Conclusions

Although pancreatic schwannoma is rare, it should be included in the list of differential diagnoses of pancreatic masses, both solid and cystic. A tumor size larger than 6.90 cm, vascular encasement, or visceral invasion should elicit suspicion of malignant transformation.

Background

Schwannomas, also known as neurilemmomas, are neoplasms arising from the Schwann cells of peripheral nerve sheaths [1, 2]. Schwannomas most frequently involve the head and neck area, major nerve trunks, and flexor aspects of the extremities. Deeply situated schwannomas are predominantly found in the retroperitoneum and posterior mediastinum but are rarely found in the trunk and gastrointestinal tract [1]. Pancreatic schwannomas are an extremely unusual variant of this neoplasm. According to a PubMed database search, 67 cases of pancreatic schwannomas have been described in the English literature over the past 40 years [3–64].

It has been reported that degenerative changes, such as cyst formation, hemorrhage, calcification, hyalinization and xanthomatous infiltration, are found in approximately two-thirds of pancreatic schwannomas [5, 6]. Degenerative changes lead to the presence of obvious variety in the appearance and size of the tumors. Preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic schwannoma can be particularly challenging. Pancreatic schwannomas may mimic other, more common pancreatic lesions, such as cystic neoplasms, solid and pseudopapillary neoplasms, pseudocysts and neuroendocrine tumors. Therefore, pancreatic schwannomas have a very high rate of misdiagnosis. Furthermore, schwannomas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) by strict definition. However, they can undergo malignant degeneration, in which case they are called malignant PNSTs (MPNSTs) [6–11]. Simple enucleation is usually sufficient for benign pancreatic schwannomas, while extensive radical resection is recommended for patients with malignant tumors. However, how to distinguish malignant from benign pancreatic schwannomas remains challenging.

Consequently, a clearer consensus on the characteristics of pancreatic schwannomas is needed. For this purpose, we present herein a case of pancreatic schwannoma in a 53-year-old male and a review of the previous literature with an emphasis on radiographic features that may help distinguish between benign and malignant tumors.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old male presented to our hospital in June 2016 with a history of intermittent periumbilical abdominal pain and lower back pain for 1 week. He did not exhibit any nausea/vomiting, jaundice or weight loss. Upon physical examination, the abdomen was soft and non-distended without evidence of hepatosplenomegaly or a palpable mass. His family history was not significant, and tumor markers (AFP, CA-125, CA19–9, and CEA) were within normal ranges.

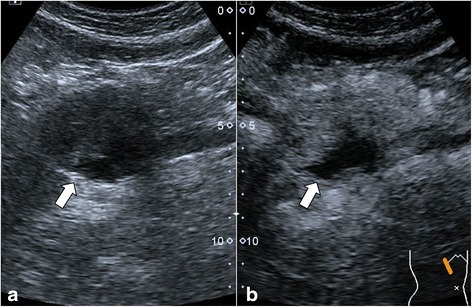

An abdominal US revealed a well-defined, hypoechoic mass in the head of the pancreas that measured 4.8 × 4.7 cm and contained an internal cystic component. On contrast-enhanced US, there was uniform enhancement of the tumor, and no intratumoral vascularity was detected with Doppler imaging (Fig. 1). Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a well-encapsulated, heterogeneous lesion at the junction of the pancreatic head and neck without calcification. On contrast-enhanced CT, there was mild and heterogeneous enhancement in the solid component of the tumor, which was less than the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. The internal cystic component was not enhanced (Fig. 2). The mass compressed nearby blood vessels, such as the portal vein and celiac trunk, without invading them. No associated dilatation of the main pancreatic duct or common bile duct was found. Additionally, there were no liver masses or pathologic lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal US. a: Linear endoscopic ultrasound demonstrating a solid-cystic, heterogeneous, well-defined hypoechoic lesion in the head process of the pancreas (arrow). b: Early contrast-enhanced ultrasound showing an echogenic peripheral zone and a hypoechoic central area compared with the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography findings. a: An unenhanced CT scan showed a 4.8 × 4.6 cm well-defined cystic and solid mass (arrow) in the pancreatic head and adjacent to the portal vein. b: Enhanced CT scan revealed a mildly enhanced mass in the arterial phase (arrow). c: A moderately enhanced mass in the portal phase (arrow). d: A cystic and solid mass on coronal reconstruction (MPR) imaging

According to these results, the mass was preliminarily considered as a solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, which disclosed a well-encapsulated 6 × 5 cm mass arising from the head of the pancreas and compression of the portal and superior mesenteric veins. A standard Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed.

Histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed a 5.5 cm, well-circumscribed, yellow-gray mass with a slightly hard consistency. Microscopically, the tumor was completely surrounded by a capsule with subcapsular lymphocytic infiltrates and abundant lymphoid follicle formation. The tumor was composed of spindle cells with wavy nuclei and mild atypia exhibiting a palisading arrangement. Nerve fiber bundles were noted at the periphery (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical staining results revealed that the tumor was strongly positive for CD-56 and S-100 but negative for CD-117, CD-34, DOG-1, desmin or smooth muscle actin. These findings were consistent with the final diagnosis of pancreatic schwannoma.

Fig. 3.

Microscopic examination. This tumor was mainly composed of spindle-shaped cells with palisading arrangement and no atypia, which is consistent with a benign schwannoma

Postoperatively, the patient recovered well, and he was discharged without incident 3 weeks after the operation. At the 8-month follow-up visit, the patient was doing well without recurrent disease, and his abdominal pain had resolved.

Discussion

Schwannomas, which were first described by Verocay in 1910, are mesenchymal neoplasms derived from Schwann cells that line peripheral nerve sheaths and do not contain neuroganglion cells [65]. However, the pancreas is an extremely uncommon site of origin for schwannomas, which arise from either the sympathetic or parasympathetic nerve fibers coursing through the pancreas [29]. A literature search was performed in March 2017. The MeSH term used in the PubMed search was ‘pancreatic schwannoma’. In addition, the reference lists of relevant articles were searched to find other eligible studies. A PubMed search of the past four decades revealed 62 articles describing 67 cases of pancreatic schwannoma in the English literature [3–64]. A total of 68 cases of pancreatic schwannoma, including our current case, were analyzed and summarized. The clinicopathological data for all 68 patients with pancreatic schwannoma was shown in Table 1. All of the data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were recorded as the means ± standard deviation (SD) and range and were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The tumor distribution was skewed in the control group, so the Wilcoxon rank sum test of two independent samples was used. Categorical variables were analyzed with the four-fold table method and the R*2 method of the Chi-squared test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to determine the optimal cut-off points of tumor size for distinguishing malignant lesions from benign lesions.

Table 1.

| n (%) or mean ± SD (range) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (n = 68) | |

| Mean | 55.7 ± 14.7 (20–87) |

| Sex (male/female), (male %) (n = 68) | 15:19 (44%) |

| Symptoms (n = 68) | |

| Asymptomatic | 23 (34%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Abdominal pain | 34 (50%) |

| Weight loss | 12 (18%) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 6 (8.8%) |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (7.4%) |

| Back pain | 4 (5.9%) |

| Abdominal mass | 3 (4.4%) |

| Anemia | 2 (2.9%) |

| Melena | 2 (2.9%) |

| Jaundice | 2 (2.9%) |

| Mean size (cm) (n = 64) | 6.1 ± 5.7 (1–33) |

| Location (n = 67) | |

| Uncinate | 9 (13%) |

| Head | 27 (40%) |

| Head + body | 3 (4.5%) |

| Body | 14 (21%) |

| Body + tail | 7 (10%) |

| Tail | 6 (9.0%) |

| Nature of tumor on imaging (n = 68) | |

| Solid | 19 (28%) |

| Cystic | 29 (43%) |

| Solid + cystic | 15 (22%) |

| Not specified | 5 (7.4%) |

| Imaging characteristics | |

| Well-defined margins (n = 59) | 47 (80%) |

| Presence of calcifications (n = 58) | 5 (8.6%) |

| Pancreatic duct/CBD dilation (n = 22) | 2 (9.1%) |

| Relation to nearby structures (n = 29) | |

| No changes to nearby structures | 12 (41%) |

| Compressed/displaced vessels | 9 (31%) |

| Encasement of vessels | 4 (14%) |

| Invasion of viscera | 3 (10%) |

| Preoperative diagnosis (n = 44) | |

| Correct | 9 (20%) |

| Incorrect | 35 (80%) |

| Cystic neoplasm | 17 (49%) |

| Serous cystic neoplasm | 3 (8.6%) |

| Mucinous cystic neoplasm | 8 (23%) |

| Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm | 7 (20%) |

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | 8 (23%) |

| Pseudocyst | 2 (5.7%) |

| Acinar cell carcinoma | 3 (8.6%) |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 6 (17%) |

| Treatment (n = 67) | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 16 (24%) |

| Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | 7 (10%) |

| Central pancreatectomy | 2 (3.0%) |

| Distal pancreatectomy +/− splenectomy | 15 (22%) |

| Enucleation | 8 (12%) |

| Surgical resection not otherwise specified (NOS) | 14 (21%) |

| Unresectable | 2 (3.0%) |

| Refused | 3 (4.5%) |

| Histology (n = 68) | |

| Benign | 60 (88%) |

| Malignant | 8 (12%) |

| Mean follow-up (months) (n = 34) | 19 ± 15.4 (3–65) |

| Died of disease | 1 |

Pancreatic schwannomas may develop in any part of the pancreas but are most commonly located in the pancreatic head. Overall, approximately one-third of patients are asymptomatic. Common symptoms are abdominal pain and weight loss, while a few patients present with nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, back pain or a palpable mass. Anemia, melena and jaundice are infrequent symptoms. Laboratory tests, including tumor markers, are usually within the normal range. Pancreatic schwannomas are usually benign and solitary. However, there may be multiple malignant schwannomas in patients with von Recklinghausen disease (VRD) [61]. In the 68 cases in this review, only 2 patients reported a history of VRD [7, 11].

Definitive diagnosis is achieved only with histological examination and immunohistochemical staining of a surgically resected specimen. Macroscopically, pancreatic schwannomas are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, homogeneous, yellow-tan nodules. Up to two-thirds of pancreatic schwannomas exhibit secondary degenerative changes, such as cyst formation, hemorrhage, hyalinization, calcification and xanthomatous infiltration [26, 37, 62]. Microscopically, typical features of pancreatic schwannomas include an organized hypercellular component (Antoni A areas) and a hypocellular component with loose myxoid stroma (Antoni B areas). Antoni B areas often have accompanying degenerative changes [4]. Benign schwannomas normally have < 5 mitotic figures per 10 high-powered fields [58]. Pancreatic schwannomas demonstrate strong positive immunohistochemical staining for S-100, vimentin, and CD-56, and they show negative staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD34, CD117 (c-kit), desmin, and smooth muscle myosin [66].

An accurate preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic schwannomas is difficult due to the nonspecific radiological appearance of these tumors, even with the use of multiple imaging modalities. Due to the variable proportions of Antoni A and B areas contained in the tumor, pancreatic schwannomas commonly appear cystic (near half of cases, 29; 43%) but may also have a completely solid structure (19; 28%) or a mixed solid and cystic pattern (15; 22%) (Table 1). Up to 80% of schwannomas exhibited well-defined margins on imaging and were also found to be well encapsulated upon gross pathological examination (Table 1). On ultrasound, a pancreatic schwannoma usually appears as a well-defined, hypoechoic lesion that shows poor contrast intake and is hypoenhanced compared to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma [22, 44]. On unenhanced CT, tumors composed of exclusively or predominantly Antoni A areas appear as well-defined, heterogeneous, hypodense, solid masses due to their high cellularity and increased lipid content, whereas tumors with high Antoni B areas appear as homogeneous cystic masses due to their low cellularity and loose myxoid stroma [56]. Contrast-enhanced CT is helpful for distinguishing between Antoni A and Antoni B areas based on their vascularity. Generally, the more vascular Antoni A areas are enhanced, whereas Antoni B areas are frequently not enhanced [56, 64]. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), schwannomas appear homogeneously hypointense on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) [45]. Sometimes, they may also appear inhomogeneously intense due to the presence of a fair amount of both Antoni A and Antoni B areas in the tumors [56]. Calcifications (5; 8.6%) and associated pancreatic ducts or common bile duct dilation (2; 9.1%) are uncommon findings but are both associated with benign tumors. Larger tumors (9; 31%) may cause the compression or displacement of nearby vessels. More rarely, tumors (4; 14%) are found to completely encase adjacent vessels or invade the duodenum and transverse colon (Table 1). Lymph node enlargement and distant metastases are typically not associated with pancreatic schwannomas. Due to the variable radiographic appearance of schwannomas, they often mimic other pancreatic tumors that share similar imaging features, leading to a high rate of misdiagnosis. The most common differential diagnosis is cystic neoplasms, such as serous or mucinous cystic neoplasms. Pancreatic schwannomas are also misdiagnosed as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, solid pseudopapillary tumors, mucinous cystadenocarcinomas, acinar cell carcinomas and pancreatic pseudocysts. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) may contribute to precise preoperative diagnosis, but its use remains controversial because of its high false-negative rate. In the 16 patients with EUS-FNA, only 8 (50%) were correctly diagnosed preoperatively with pancreatic schwannoma.

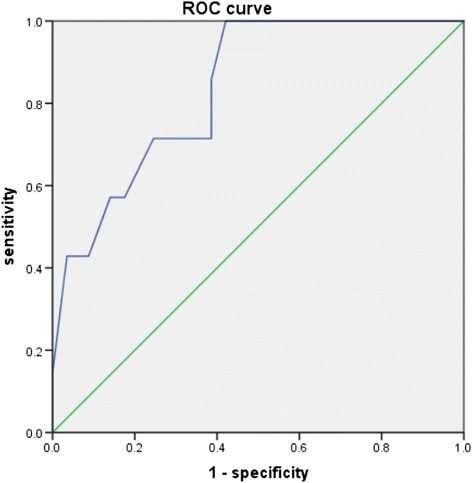

The vast majority of pancreatic schwannomas (approximately 88.2%) are benign [3]. Malignant transformation is extremely rare. Only 8 cases (11.8%) of malignant pancreatic schwannoma have been described in the English literature [6–11]. Some investigators have attempted to correlate the tumor’s characteristics on imaging with its malignant potential. Moriya et al. [4] reported that larger tumors correlated with greater malignant potential. This was confirmed in our current analysis of an updated dataset. The characteristics of benign and malignant pancreatic schwannomas were summarized in Table 2. Pancreatic schwannomas had a mean size of 5.2 ± 4.0 cm for benign tumors and 14.0 ± 10.3 cm for malignant tumors, a difference that was statistically significant. A ROC curve of tumor size was constructed with an area under the curve calculated as 0.836, a cut-off of 6.90 cm, a sensitivity of 71.4% and a specificity of 75.4% (Fig. 4). We further analyzed other tumor characteristics on imaging to determine the predictors of malignancy on pathological examination. However, there was no correlation between whether tumors appeared to be solid, cystic, or have a mixed pattern as a predictor of malignancy (Table 2). Benign tumors were significantly more likely than malignant ones to exhibit well-defined margins on imaging, whereas the presence of calcifications and pancreatic duct or common bile duct dilation was not significant. However, the presence of well-defined margins did not exclude malignancy because 2 cases of malignant schwannoma were also initially described as having well-defined radiographic margins. Moreover, malignant tumors were more likely than benign tumors to cause changes in adjacent structures, including the encasement of nearby vessels, such as the portal vessels, celiac trunk, and superior mesenteric vessels, as well as the invasion of adjacent organs, such as the small and large bowel on surgical or pathological examination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics between benign and malignant pancreatic schwannomas

| Benign (n = 60) | Malignant (n = 8) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 56.3 ± 14.4 (20–87) | 51.1 ± 17.7 (24–74) | 0.358 |

| Sex (male/female), (male %) | 9:11 (45%) | 3:5 (37.5%) | 1.000 |

| Mean size (cm) | 5.2 ± 4.0 (1–20) | 14.0 ± 10.3 (5–33) | 0.004 |

| Location | |||

| Uncinate | 9 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0.228 |

| Head | 22 (37%) | 5 (71%) | |

| Head + body | 3 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Body | 14 (23%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Body + tail | 6 (10%) | 2 (29%) | |

| Tail | 6 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Nature of tumor on imaging | |||

| Solid | 17 (30%) | 2 (25%) | 0.845 |

| Cystic | 26 (46%) | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Solid + cystic | 13 (23%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Not specified | 4 (7.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Imaging characteristics | |||

| Well-defined margins | 45 (96%) | 2 (33%) | 0.009 |

| Presence of calcifications | 5 (9.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Pancreatic duct/CBD dilation | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Relation to nearby structures | |||

| No changes in nearby structures | 12 (52%) | 0 (0%) | < 0.001 |

| Compressed/displaced vessels | 9 (39%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Encasement of vessels | 2 (8.7%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Invasion of viscera | 0 (0%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Treatment | |||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 13 (22%) | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | 7 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Central pancreatectomy | 2 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy +/− splenectomy | 13 (19%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Enucleation | 8 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Surgical resection NOS | 13 (19%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Unresectable | 0 (0%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Refused | 3 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mean follow-up (months) | 19.4 ± 16.0 (3–65) | 16.3 ± 11.6 (4–28) | |

| Died of disease | 0 | 1 | |

Fig. 4.

ROC curve for tumor size to distinguish malignant pancreatic schwannoma from benign tumors (area under the curve: 0.836, cut-off: 6.90 cm, sensitivity: 71.4%, specificity: 75.4%)

The management of pancreatic schwannomas is guided by location and histological results. Because most of these tumors are benign and malignant transformation is rare, simple enucleation is usually sufficient if pathology is confirmed before surgery [63]. In cases of large tumors, especially those exhibiting malignant behavior (infiltration of tissue), the presence of intangibility in frozen section or close proximity to major vessels, an oncological margin-negative resection is recommended [6]. In a review of treatments, the most common type of surgical resection was pancreaticoduodenectomy, followed by distal pancreatectomy with/without splenectomy, enucleation, pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, and central pancreatectomy. The high frequency of extensive radical resection may reflect the difficulties in obtaining an accurate preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic schwannomas and in distinguishing these lesions from other pancreatic neoplasms. In such cases, intraoperative frozen sections should be performed to help establish the diagnosis of a benign schwannoma and avoid more extensive resection [4]. Following tumor excision, the long-term prognosis of pancreatic schwannoma is excellent, with no cases of recurrence over a mean follow-up of 19 ± 15.4 months (range 3–65 months).

Conclusions

Although pancreatic schwannoma is rare, it should be included in the list of differential diagnoses of pancreatic masses, both solid and cystic. A tumor size larger than 6.90 cm, vascular encasement, or visceral invasion should elicit suspicion of malignant transformation.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571750), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2014A030311018 and 2015A030313043), and S&T Programs (2014A020212125) of Guangdong Province. The Grants-in-Aid supported this study just financially, and had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because of patient privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFP

Alpha fetoprotein

- CA-125

Carbohydrate antigen 125

- CA19–9

Carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CT

Computed tomography

- DOG-1

Discovered on GIST-1

- EUS-FNA

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration

- GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PNSTs

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors

- ROC curves

Receiver-operating characteristic curves

- SD

Standard deviation

- T1WI

T1-weighted imaging

- T2WI

T2-weighted imaging

- US

Ultrasound

- VRD

Von Recklinghausen disease

Authors’ contributions

STF, WC and ZPL designed the research and were responsible for quality control of data. WC performed a standard Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy. BS, YJ, YT and ZD performed the follow-up survey and collected the data. YJ and YL performed the statistical analysis of data. YM, STF and BS wrote the manuscript and all authors edited and made critical revisions to the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuntong Ma, Email: ym2271@gmail.com.

Bingqi Shen, Email: gzshenbq@163.com.

Yingmei Jia, Email: 1043613309@qq.com.

Yanji Luo, Email: 583149136@qq.com.

Yisu Tian, Email: 529307943@qq.com.

Zhi Dong, Email: asrachel@126.com.

Wei Chen, Email: chenw57@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Zi-Ping Li, Email: liziping163@163.com.

Shi-Ting Feng, Email: fst1977@163.com.

References

- 1.Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, Skordalaki A, Zarampoukas T, Drevelengas A. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52(3):229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu SY, Sun K, Owusu-Ansah KG, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS, et al. Central pancreatectomy for pancreatic schwannoma: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(37):8439–8446. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moriya T, Kimura W, Hirai I, Takeshita A, Tezuka K, Watanabe T, et al. Pancreatic schwannoma: case report and an updated 30-year review of the literature yielding 47 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(13):1538–1544. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i13.1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paranjape C, Johnson SR, Khwaja K, Goldman H, Kruskal JB, Hanto DW. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcome of pancreatic Schwannomas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8(6):706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stojanovic MP, Radojkovic M, Jeremic LM, Zlatic AV, Stanojevic GZ, Jovanovic MA, et al. Malignant schwannoma of the pancreas involving transversal colon treated with en-bloc resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(1):119–122. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombs RJ. Case of the season. Malignant neurogenic tumor of duodenum and pancreas. Semin Roentgenol. 1990;25(2):127–129. doi: 10.1016/0037-198X(90)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggermont A, Vuzevski V, Huisman M, De Jong K, Jeekel J. Solitary malignant schwannoma of the pancreas: report of a case and ultrastructural examination. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36(1):21–25. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930360106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liegl B, Bodo K, Martin D, Tsybrovskyy O, Lackner K, Beham A. Microcystic/reticular schwannoma of the pancreas: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Pathol Int. 2011;61(2):88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller Pedersen V, Hede A, Graem N. A Solitary malignant schwannoma mimicking a pancreatic pseudocyst. A case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1982;148(8):697–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh MM, Brandspigel K. Gastrointestinal bleeding due to pancreatic schwannoma complicating von Recklinghausen's disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;97(6):1550–1551. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abu-Zaid A, Azzam A, Abou Al-Shaar H, Alshammari AM, Amin T, Mohammed S. Pancreatic tail schwannoma in a 44-year-old male: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:416–713. doi: 10.1155/2013/416713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aggarwal G, Satsangi B, Shukla S, Lahoti BK, Mathur RK, Maheshwari A. Rare asymptomatic presentations of schwannomas in early adolescence: three cases with review of literature. Int J Surg. 2010;8(3):203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiyoshi T, Ueda Y, Yanai K, Yamaguchi H, Kawamoto M, Toyoda K, et al. Melanotic schwannoma of the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34(6):550–553. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almo KM, Traverso LW. Pancreatic schwannoma: an uncommon but important entity. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5(4):359–363. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(01)80062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonini F, Santinelli A, Macarri G. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of an unusual pancreatic mass. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):e25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barresi L, Tarantino I, Granata A, Traina M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of pancreatic schwannoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(6):523. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown SZ, Owen DA, O'Connell JX, Scudamore CH. Schwannoma of the pancreas: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 1998;11(12):1178–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bui TD, Nguyen T, Huerta S, Gu M, Hsiang D. Pancreatic schwannoma. A case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2004;5(6):520–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burd DA, Tyagi G, Bader DA. Benign schwannoma of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159(3):675. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.3.1503050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciledag N, Arda K, Aksoy M. Pancreatic schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(6):2741–2743. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crino SF, Bernardoni L, Manfrin E, Parisi A, Gabbrielli A. Endoscopic ultrasound features of pancreatic schwannoma. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5(6):396–398. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.195873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.David S, Barkin JS. Pancreatic schwannoma. Pancreas. 1993;8(2):274–276. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199303000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Benedetto F, Spaggiari M, De Ruvo N, Masetti M, Montalti R, Quntini C, et al. Pancreatic schwannoma of the body involving the splenic vein: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(7):926–928. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorsey F, Taggart MW, Fisher WE. Image of the month. Pancreatic schwannoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145(9):913–914. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.172-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duma N, Ramirez DC, Young G, Nikias G, Karpeh M, Bamboat ZM. Enlarging pancreatic Schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Pract. 2015;5(4):793. doi: 10.4081/cp.2015.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ercan M, Aziret M, Bal A, Şentürk A, Karaman K, Kahyaoğlu Z. Pancreatic schwannoma: a rare case and a brief literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;22:101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fasanella KE, Lee KK, Kaushik N. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Benign schwannoma of the pancreatic head. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):489–830. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman L, Philpotts LE, Reinhold C, Duguid WP, Rosenberg L. Pancreatic schwannoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1997;15(1):99–105. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199707000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Garlaschi G. Pancreatic schwannoma: report of three cases. Clin Radiol. 1995;50(7):492–495. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(05)83168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta A, Subhas G, Mittal VK, Jacobs MJ. Pancreatic schwannoma: literature review. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(3):168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirabayashi K, Yasuda M, Umemura S, Itoh H, Itoh J, Yazawa N, et al. Cytological features of the cystic fluid of pancreatic schwannoma with cystic degeneration. A case report. JOP. 2008;9(2):203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiao WC, Lin PW, Chang KC. Benign retroperitoneal schwannoma mimicking a pancreatic cystic tumor: case report and literature review. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 1998;45(24):2418–2420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.J D, R S, K C, Devi NR. Pancreatic schwannoma- a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(7):FD15–FD16. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8465.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim G, Choi YS, Kim HJ, Do JH, Park ES. Pancreatic benign schwannoma: combined with hemorrhage in an internal cyst. J Dig Dis. 2011;12(2):138–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinhal VA, Ravishankar TH, Melapure AI, Jayaprakasha G, Range Gowda BC, Manjunath BC. Pancreatic schwannoma: report of a case and review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2010;72(Suppl 1):296–298. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0112-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JS, Kim HS, Jung JJ, Han SW, Kim YB. Ancient schwannoma of the pancreas mimicking a cystic tumor. Virchows Arch. 2001;439(5):697–699. doi: 10.1007/s004280100492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S, Ai SZ, Owens C, Kulesza P. Intrapancreatic schwannoma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(2):132–135. doi: 10.1002/dc.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liessi G, Barbazza R, Sartori F, Sabbadin P, Scapinello A. CT and MR imaging of melanocytic schwannomas; report of three cases. Eur J Radiol. 1990;11(2):138–142. doi: 10.1016/0720-048X(90)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melato M, Bucconi S, Marus W, Spivach A, Perulli A, Mucelli RP. The schwannoma: an uncommon type of cystic lesion of the pancreas. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1993;25(7):385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morita S, et al. Pancreatic Schwannoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29(10):1093–1097. doi: 10.1007/s005950050651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mourra N, Calvo J, Arrive L. Incidental finding of cystic pancreatic Schwannoma mimicking a Neuroendocrine tumor. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24(2):149–150. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mummadi RR, Nealon WH, Artifon EL, Fleming JB, Bhutani MS. Pancreatic Schwannoma presenting as a cystic lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(2):341. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishikawa T, Shimura K, Tsuyuguchi T, Kiyono S, Yokosuka O. Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS of pancreatic schwannoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):463–464. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Novellas S, Chevallier P, Saint Paul MC, Gugenheim J, Bruneton JN. MRI features of a pancreatic schwannoma. Clin Imaging. 2005;29(6):434–436. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohbatake Y, Makino I, Kitagawa H, Nakanuma S, Hayashi H, Nakagawara H, et al. A case of pancreatic schwannoma - the features in imaging studies compared with its pathological findings: report of a case. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014;7(3):265–270. doi: 10.1007/s12328-014-0480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okuma T, Hirota M, Nitta H, Saito S, Yagi T, Ida S, et al. Pancreatic schwannoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2008;38(3):266–270. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oshima M, Yachida S, Suzuki Y. Pancreatic schwannoma in a 32-year-old woman mimicking a solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(1):e1–e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paik KY, Choi SH, Heo JS, Choi DW. Solid tumors of the pancreas can put on a mask through cystic change. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pecero-Hormigo MD, Costo-Campoamor A, Cordero PG, Fernandez-Gonzalez N, Molina-Infante J. Pancreatic tail schwannoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Poosawang W, Kiatkungwankai P. Pancreatic schwannoma: a case report and review of literature. J Med Assoc Thail. 2013;96(1):112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rathod KJ, Kate V, Badhe B. Cystic retroperitoneal swelling occupying the whole abdomen. Diagnosis: Schwannoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):e7–e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soumaoro LT, Teramoto K, Kawamura T, Nakamura N, Sanada T, Sugihara K, et al. Benign schwannoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9(2):288–290. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steven K, Burcharth F, Holm N, Pedersen IK. Single stage pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple's procedure), radical cystectomy and bladder substitution with the urethral Kock reservoir. Case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1994;28(2):199–200. doi: 10.3109/00365599409180501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugiyama M, Kimura W, Kuroda A, Muto T. Schwannoma arising from peripancreatic nerve plexus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(1):232. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.1.7785620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suzuki S, Kaji S, Koike N, Harada N, Hayashi T, Suzuki M, et al. Pancreatic schwannoma: a case report and literature review with special reference to imaging features. JOP. 2010;11(1):31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tafe LJ, Suriawinata AA. Cystic pancreatic schwannoma in a 46-year-old man. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2008;12(4):296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan G, Vitellas K, Morrison C, Frankel WL. Cystic schwannoma of the pancreas. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003;7(5):285–291. doi: 10.1016/S1092-9134(03)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tofigh AM, Hashemi M, Honar BN, Solhjoo F. Rare presentation of pancreatic schwannoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:268. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urban BA, Fishman EK, Hruban RH, Cameron JL. CT findings in cystic schwannoma of the pancreas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16(3):492–493. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199205000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Val-Bernal JF, Mayorga M, Sedano-Tous MJ. Schwannomatosis presenting as pancreatic and submandibular gland schwannoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209(12):817–822. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.von Dobschuetz E, Walch A, Werner M, Hopt UT, Adam U. Giant ancient schwannoma of pancreatic head treated by extended pancreatoduodenectomy. Pancreatology. 2004;4(6):505–508. doi: 10.1159/000080247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.YL W, Yan HC, Chen LR, Chen J, Gao SL, Li JT. Pancreatic benign schwannoma treated by simple enucleation: case report and review of literature. Pancreas. 2005;31(3):286–288. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000169727.94230.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.RS Y, Sun JZ. Pancreatic schwannoma: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31(1):103–105. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verocay J. Zur Kenntnis der Neurofibrome. Beitr Pathol Anat Allg Pathol. 1910;48:1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weiss SW, Langloss JM, Enzinger FM. Value of S-100 protein in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors with particular reference to benign and malignant Schwann cell tumors. Lab Investig. 1983;49(3):299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because of patient privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.