Abstract

Long-lived, donor-reactive memory B cells (Bmem) can produce alloantibodies that mediate transplant injury. Autophagy, an intrinsic mechanism of cell organelle/component recycling, is required for Bmem survival in infectious and model antigen systems but whether autophagy impacts alloreactive Bmem is unknown. We studied mice with an inducible yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) reporter expressed under the Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase (AID) promoter active in B cells undergoing germinal center reactions. Up to 12 months after allogeneic sensitization, splenic YFP+ B cells were predominantly IgD−IgM−IgG+ and expressed CD73, CD80, and PD-L2, consistent with Bmem. Labeled cells contained significantly more cells with autophagosomes, and autophagosomes per cell than unlabeled, naïve B cells. To test for a functional link, we quantified alloantibody formation in mice with B cells conditionally deficient in the requisite autophagy gene ATG7. These experiments revealed absent B cell ATG7: a) prevented B cell autophagy, b) inhibited secondary alloantibody responses without altering primary alloantibody formation and c) diminished frequencies of alloreactive Bmem. Pharmacological autophagy inhibition with 3-methyladenine had similar effects on wild type mice. Together with new documentation of increased autophagosomes within human Bmem, our data indicate that targeting autophagy has potential for eliminating donor-reactive Bmem in transplant recipients.

Introduction

Antigen recognition via the B cell receptor (BCR) in conjunction with cognate T cell interactions helps promote differentiation of IgD+IgM+ naïve B cells into antibody secreting B cells, plasma cells (PC) and class switched (i.e. IgG+) Bmem1. Reactivation of long-lived IgDnegIgG+ murine Bmem permits them to rapidly develop into antibody secreting cells (ASC). Resultant anamnestic antibody responses develop with accelerated kinetics and higher affinity than primary responses and are considered essential for protection against pathogen reinfection1.

Analogous primary and anamnestic responses induced to alloantigen represent significant barriers to transplant survival.2, 3 Current concepts are that donor specific antibodies (DSA) generated from host exposure to alloantigen via blood transfusions, pregnancy, heterologous immunity and/or prior transplants are responsible for antibody mediated allograft injury that results in graft failure.2 While long-lived PC can produce DSA in sensitized mice and humans, emerging evidence indicates that post-transplant DSA in sensitized individuals commonly derive from reactivation of Bmem.3 Current desensitization regimens are largely focused on neutralizing or removing circulating serum antibody (e.g. anti-thymocyte globulin and plasmapheresis) or eliminating PC (e.g. bortezomib). Recognition that donor-reactive Bmem, even in the absence of detectable DSA, are strongly associated with antibody-mediated kidney allograft injury3 supports the need to better understand the mechanisms of Bmem cell function and survival to guide improved therapeutic interventions.

Autophagy is a cell intrinsic process involving sequestration of organelles or cytoplasmic constituents within de novo organelles called autophagosomes and degradation after fusion with a lysosome. Autophagy is a powerful homeostatic mechanism and is important for removing damaged organelles or repurposing unused cytoplasmic material. The autophagy pathway involves two distinct ubiquitin ligase-like pathways that require the E1-ligase like activity of the protein autophagy related gene7 (ATG7).4 The first of these pathways facilitates conjugation of ATG5 to ATG12, a process requiring initial activation of ATG12 via ATG7-mediated creation of a thioester bond5. ATG7 is also necessary for the conjugation of a phospholipid, phosphatidylethanolamine, to microtubule associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) that, along with conjugation of ATG5 to ATG12, permits expansion of the autophagosome.6 The phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form of LC3, termed LC3-II, remains part of the completed autophagosome. This phenomenon is unique to LC3 and is the basis for most experimental autophagy measurement assays.7

Canonically, autophagy is an adaptation to insufficient nutrient availability.8 Increasing evidence suggests that autophagy induction occurs via multiple stimuli including pattern recognition receptors (PRR), cytokines, oxidative stress, and ER stress.9–12 Autophagy is also necessary for the maintenance of neurons and other long-lived cells.13 Emerging evidence suggests that B cell autophagy is necessary for anti-pathogen Bmem survival but autophagy’s effects on Bmem-dependent alloantibody production following transplantation remain unknown.14

Herein we show that B cell intrinsic autophagy is required for allospecific Bmem cell function in mice. Our new data indicate that pharmacological autophagy inhibition can prevent anamnestic DSA responses to alloantigen. Together with our new observation that human Bmem contain autophagomes, our findings support the need to develop and test analogous desensitization strategies in alloantigen exposed human transplant candidates.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild type (WT) C57BL/6 (B6), BALB/cJ (BALB/c), and B6 CD19-Cre transgenic (Tg) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor ME. AID-Cre-ERT2-Rosa26-eYFP mice were provided by N. Papavasiliou (Rockefeller Univ, NY, NY) and have been previously described.15 ATG7fl/fl mice (B6 background)16 were crossed to CD19-Cre mice to produce CD19Cre × ATG7fl/fl. GFP-LC3 reporter mice were provided by Zhenyue Yue (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai).17 All animals were housed in the Center for Comparative Medicine and Surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai under IACUC approval.

In vivo animal studies

Sensitization was performed with two i.p. injections of 15 × 106 donor spleen cells into recipient allogeneic recipients administered two weeks apart. Vascularized heterotopic heart transplants were performed as previously described18 by the Mount Sinai Microsurgery Core. In selected experiments (see results section) recipients were treated with a single dose of MR1 (250 μg iv 1 day prior to transplant bioexcell), or 3-methyladenine (Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, MO) 24mg/kg every five days starting five weeks after sensitization and continuing until time of sacrifice.

Western Blot

Western blotting was conducted as previously described19 using anti-LC3 (MBL Woburn, MA), anti-p62(MBL), anti-GAPDH (Sigma), HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson Immunoresearch West Grove, PA) and goat anti-guinea pig (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA). Band intensity quantification was performed using Image Studio (Licor Lincoln, NE).

Flow Cytometry

Eight–parameter flow cytometric analysis was performed as previously described20 on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer using DiVA software package (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data were analyzed using Flow Jo software by Tree Star (Ashland, OR). Murine cell surface staining was performed using fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibodies reactive to B220, IgD, IgM, and IgG, all purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and CD73, CD80, PD-L2 BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Surface staining in human cells was performed with fluorescently labeled antibodies reactive to CD19, IgD, and CD27, BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). For tetramer staining, biotinylated monomers of H-2Kd loaded with a peptide whose sequence (SYIPSAEKI) possesses a defined specificity22 were obtained from the NIH tetramer Core Facility (Atlanta, GA). Tetramerization was performed per NIH protocol (http://tetramer.yerkes.emory.edu/support/protocols#10) with streptavidin conjugated phycoerythrin and allophycocyanin (Thermo-fisher, USA). One μl of each tetramer was added to 5 million cells for each condition tested.

B Cell Isolation

Primary murine B cells were obtained from freshly isolated splenic single cell suspensions using EasySep™ Mouse B Cell Isolation Kit STEMCELL Technologies (Cambridge, MA) per manufacturer’s instructions. Purified YFP+ and YFPneg AID-CreERT2-eYFP B cells were enriched as above and then sorted to > 90% purity on a SONY SH800Z sorter (San Jose, CA) prior to ELISPOT. For human B cell experiments, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated as previously described20 from leukopacs of anonymous donors purchased from the New York Blood Bank. B cells were then isolated from total PBMCs using EasySep™ Human B Cell Isolation Kit.

Imaging Flow Analysis

Quantification of autophagosomes was accomplished using image analysis flow cytometry as determined by LC3 puncta. Mouse and human B cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde then stained with an anti-LC3 DyLight 650 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). Cell images were acquired on an ImageStream flow cytometer (Amnis Seattle, WA) and analyzed with the IDEAS analysis software (Amnis). Single-color controls were used for creation of a compensation matrix that was applied to all files to correct for spectral crosstalk. Debris and dead cells were identified by high pixel intensity correlation (Bright Detail Similarity score) across all channels and were excluded from the analysis.

To quantify LC3 spots per B cell, masks were created to identify DyLight 650 or GFP intensity peaks p-fold greater than the background with a diameter of r number of pixels. The optimal of p and r were determined independently for each experiment. Controls for the efficacy of the algorithm were performed using unstained samples.21 The number of individual masks in each cell was enumerated and histograms of the distribution of spots per cell obtained for each sample.

Donor-Specific Alloantibody

To quantify class I IgG DSA serial dilutions of recipient serum were incubated with 250,000 freshly isolated donor thymocytes. Cells were washed and then incubated with a FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (ebioscience). Detection of antibody binding was accomplished by flow cytometry on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (at least 10,000 events per sample). Negative controls to define background staining included use of serum from naïve animals and thymocytes mixed with secondary antibody in the absence of serum.

B cell ELISPOT

ELISPOTs were performed using MABTECH B cell ELISPOT kits according manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 96-well PVDF plates were coated with IgG capture antibody overnight. Isolated spleen cells in RPMI 5% FBS (Thermo-Fisher) were plated and incubated overnight. The following day, plates were washed and incubated with biotinylated detection agents (either anti-IgG or monomers of H-2Kd). Biotinylated H-2Kd monomers able to detect a subset of alloreactive ASC (peptide sequence SYIPSAEKI), were provided by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility.22

Statistics

For all experiments, results are expressed as mean +/− SEM. Determination of significance was done using a Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism La Jolla, CA) with a p < 0.05 considered significant. The number of punctate containing B cells in sets of 3MA or control treated GFP-LC3 mice were compared using a Fisher’s Exact Test with p<0.05 considered significant.

Results

Identification of alloantigen-induced Bmem by fate mapping

To identify allospecific Bmem in vivo we employed a mouse model with an inducible YFP reporter driven by the promoter for Activation Induced Cytidine Deaminase (AID), a protein restricted to B cells and required for GC formation and affinity maturation.15 Tamoxifen treatment of AID-expressing AID-CreERT2-eYFP mice produces cleaveage of loxP sites surrounding a ‘stop’ codon downstream of the Rosa26 promoter enabling irreversible YFP production, and permanently identifying B cells that have undergone GC reactions related to affinity maturation and memory cell formation.15

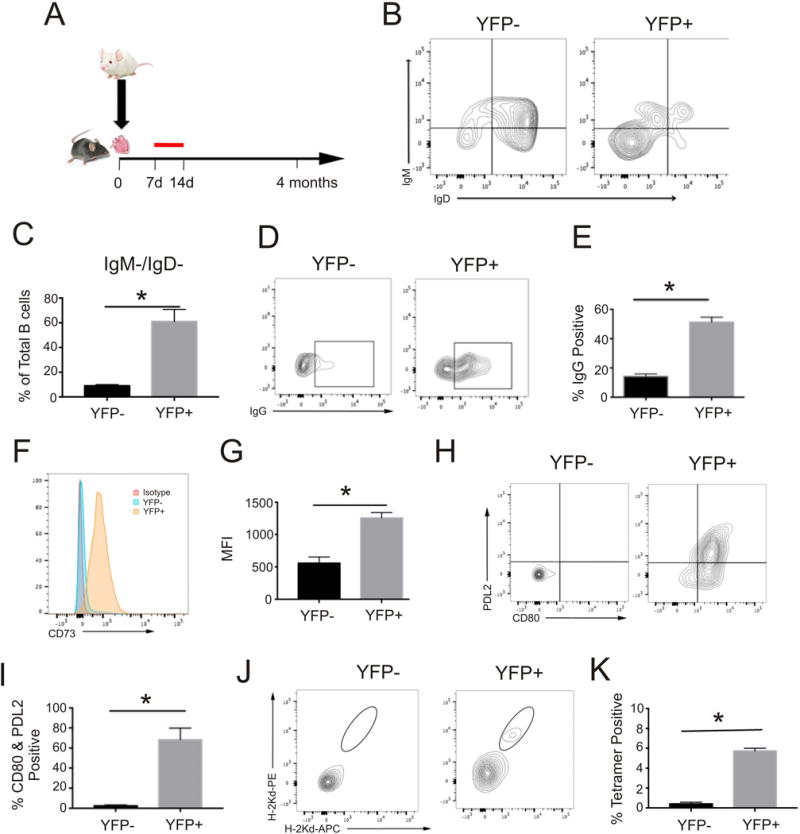

We transplanted BALB/c hearts into B6 AID-CreERT2-eYFP mice and treated the recipients with tamoxifen from days 7–14 (Figure 1A) to irreversibly label B cells engaged in GC reactions during that time period. Four months later, analyses showed that YFP+ splenic B cells were predominantly IgDnegIgMnegIgG+ consistent with a class-switched memory phenotype (Figure 1B–E). In contrast, the YFPneg population was overwhelmingly IgD+IgM+IgGneg (Figure 1B–E). In comparison to YFPneg naïve B cells, YFP+ B cells from mice sensitized with BALB/c splenocytes 12 months prior expressed higher levels of CD73 and contained a higher frequency of CD80/PD-L2 double positive cells (Fig 1F–I) consistent with previous findings by others indicative of a memory phenotype.23, 24 When we analyzed splenic B cells from these mice for binding to donor H-2Kd by dual tetramer staining and flow cytometry22 (Figure 1 J–K) we observed significantly higher frequencies of Kd-reactive B cells within the YFP+ population. Control experiments showed that labeling naïve mice yielded a YFP+ population capable of producing IgG but not DSA (Supplemental Figure 1). Together, the data support the conclusion that that YFP+ cells generated during allosensitization in this system are predominantly IgG+ Bmem that are enriched for reactivity to donor MHC.

Figure 1.

Characterization of YFP+ B cells following allosensitization. (A) Schematic of experimental design: B6 AID-CreERT2-eYFP mice received BALB/c heterotopic heart transplants (A–E) or BALB/c splenocyte injections (F–K) followed by tamoxifen administration (red line) on days 7–14 after exposure. Animals were sacrificed 4 months after heart transplant or twelve months after splenocyte injections and then analyzed. B. Representative contour plots of surface immunoglobulin M and D expression in YFPneg and YFP+ B cell populations from mice four months after transplantation. Lower left quadrant double negative proportion was quantified (C) and further analyzed for IgG surface expression (D) and the percentage positive (E) was quantified (n=4 separate recipients *p<0.05 YFP+ vs YFPneg, C and E). Representative (F) histogram of cell surface CD73 staining, (H) contour plots of PD-L2 and CD80 expression and (J) contour plots from two-color tetramer staining and associated quantification of (G) CD73 MFI, (I) %CD80/PD-L2 double positive, and (K) tetramer positive population in YFPneg and YFP+ B cells 12 months after sensitization (n=3 separate mice *p<0.05 YFP+ vs YFPneg, G, I, and K).

Increased Autophagy in Bmem

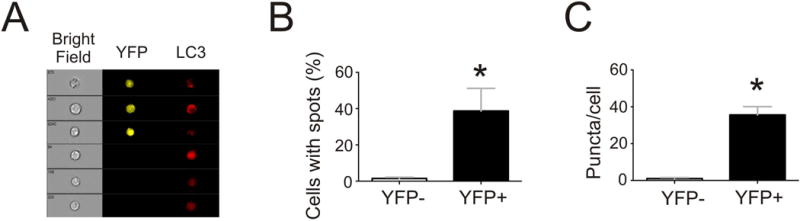

During autophagy induction, LC3 molecules coalesce onto nascent autophagosome membranes, appearing as fluorescent puncta that can be quantified by imaging flow cytometry. We analyzed and compared LC3 expression patterns by imaging flow cytometry in the YFP+ Bmem and YFPneg B cells from recipients of allogeneic BALB/c hearts four months after transplant (Figure 2A). These studies revealed significantly higher frequencies of punctate LC3+ cells and more punctate regions per cell in the YFP+ cells (Figure 2B,C). In conjuction with our documentation that the YFP+ population is enriched for donor-reactive B cells (Figure 1), our findings confirm increased autophagy in Bmem and provide evidence for ongoing autophagy within alloreactive Bmem.

Figure 2.

Quantification of Autophagy in Memory B Cells. A. Splenic B cells were isolated from AID-CreERT2-eYFP recipients of BALB/c hearts four months after transplant and analyzed on an AMNIS imaging flow cytometer. Representative bright field and fluorescence images from analyzed B cells of YFP+ (top three rows) and YFPneg (bottom three rows) demonstrating punctate versus diffuse LC3 staining in the populations, respectively. B–C. Quantification of the percentage cells containing fluorescent puncta (B) and the number of fluorescent puncta per cell (C) in YFPneg and YFP+ B cells (n=4 separate recipients *p<0.05 YFP+ vs YFPneg).

Secondary alloantibody responses require B cell autophagy

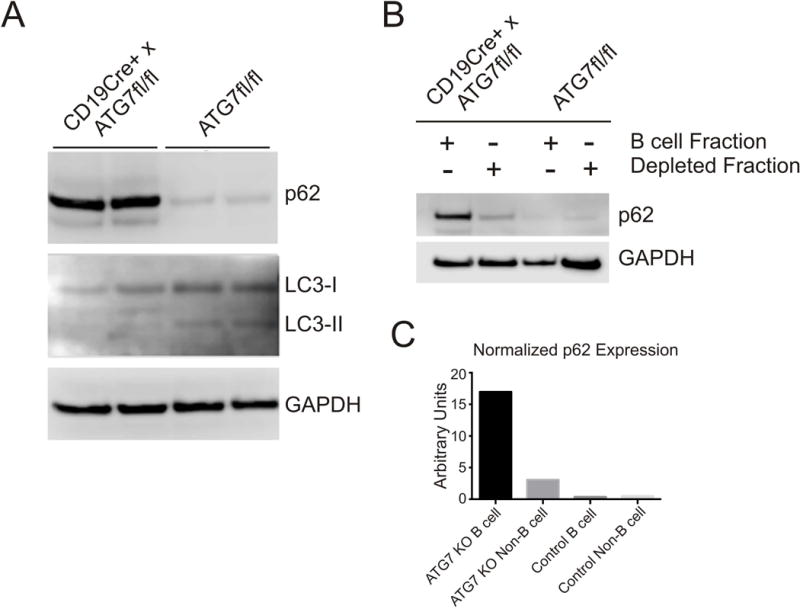

In an effort to link B cell autophagy to Bmem function we used CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl conditional knockout mice, in which deletion of ATG7 is restricted to B cells.14 Absence of ATG7 prevents activation of LC3-I to LC3-II, thereby impairing autophagosome formation/function.6 In confirmation of the expected phenotype, B cells from CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice do not contain LC3-II and, as further evidence of impaired autophagic degradation, have increased abundance of autophagy substrate p62 compared to controls (Figure 3A). Control experiments performed with B cell depleted spleen cells from CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice and ATG7fl/fl controls confirmed that the autophagy defect is restricted to B cells (Figure 3B,C).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of B Cell Autophagy in CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl Mice. (A). Immunoblot for autophagy substrate p62, LC3 I, LC3 II, and GAPDH (loading control) using lysates of isolated B cells from CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl and ATG7fl/fl littermate controls (n=2 mice in each group). B–C. Immunoblot for p62 and GAPDH (B) with quantification (C) of B cell and B cell depleted spleen cell fractions from CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl and littermate control mice probed for p62.

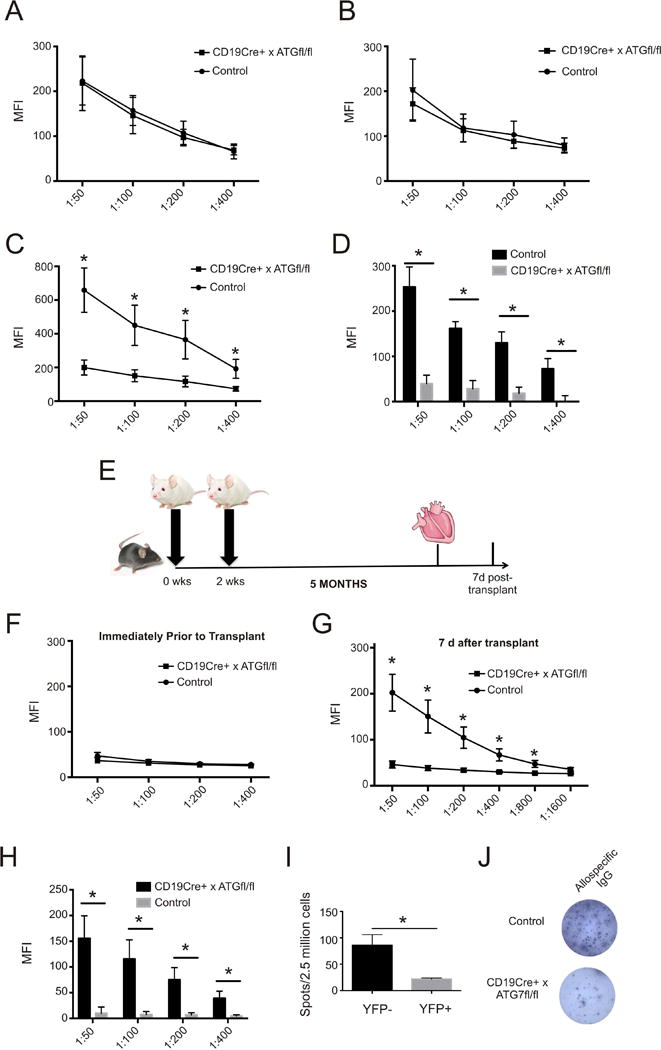

To determine whether B cell autophagy affects secondary antibody recall responses, we quantified and compared the kinetics of serum DSA (anti-donor class I MHC) in CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice and control littermates following primary and secondary stimulations with alloantigens. Two weeks after sensitization with allogeneic spleen cell injections into naïve CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl and control ATG7fl/fl mice we observed identical titers of serum IgG DSA(Figure 4A). Eight weeks after sensitization serum IgG DSA titers had fallen equivalently in both groups (Figure 4B). We next challenged both groups of sensitized animals, eight weeks after initial sensitization, with BALB/c spleen cells and measured serum IgG DSA beginning five days later, a time point too early for initiation of a de novo class-switched antibody response. Whereas IgG DSA titers increased rapidly and significantly in the control ATG7 fl/fl animals consistent with known kinetics of a secondary response1, we observed significantly impaired induction of IgG DSA in CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice(Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Primary and Secondary Alloantibody Responses in Mice with Conditional Deletion of ATG7. (A). Relative binding (mean fluorescence intensity, MFI), in diluted serum of recipient CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl and control littermates (ATG7fl/fl), of IgG to donor thymocytes at 2 weeks and (B) 8 weeks after initial sensitization with BALB/c spleen cell injections (n=7 mice in each group representing two separate experiments). Above mice were challenged at 8 weeks with repeat injection of 15×106 donor spleen cells and the relative binding (C) of their diluted serum samples and change in relative binding (D) between pre- and post- challenge assays were measured five days later (n=7 mice per group *p<0.05 CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl vs controls). (E) Experimental design of heterotopic heart transplantation experiments. (F) Relative binding of serum from CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl and control littermates five months after sensitization with (G) corresponding measurements from serial serum dilutions of the same animals seven days after transplant and (H) change in relative pre- and post-transplant binding (*p<0.05 CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl vs controls, n=6 per group representing two sets of experiments). Quantification (I) and representative images (J) of B cell ELISPOTS to detect alloreactive antibody secreting cells using spleen cells of sensitized mice 7 days after transplantation (n=4 mice in each group from one experiment *p<0.05 CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl vs controls).

In an effort to test the effects of B cell autophagy in a system that mimics clinical transplantation into sensitized recipients, we next injected CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice and control ATG7fl/fl littermates with BALB/c spleen cells, and 5 months later transplanted them with a BALB/c heart allografts under the cover of anti-CD40L mAb MR1 (the latter to limit anti-donor T cell responses and retard cellular rejection, Figure 4E). As in the previous experiments(Figure 4A–D), the kinetics and titers of the primary DSA responses were similar between the groups at all time points, including 5 months after the immunization (immediately prior to transplant), where only low titers of IgG DSA were detected(Figure 4F). Seven days after heart transplantation, sera of CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice contained significantly lower titers of IgG DSA than control mice(Figure 4G) that represented modest changes from pre-transplant levels and were significantly less than the changes in control mice (Figure 4H).

We next isolated splenic B cells from the same animals on day 7 post-transplant to test them for their ability to produce donor-reactive (H-2Kd) IgG by ELISPOT. These assays showed significantly lower frequencies of allospecific ASCs in CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice (Figure 4I,J).

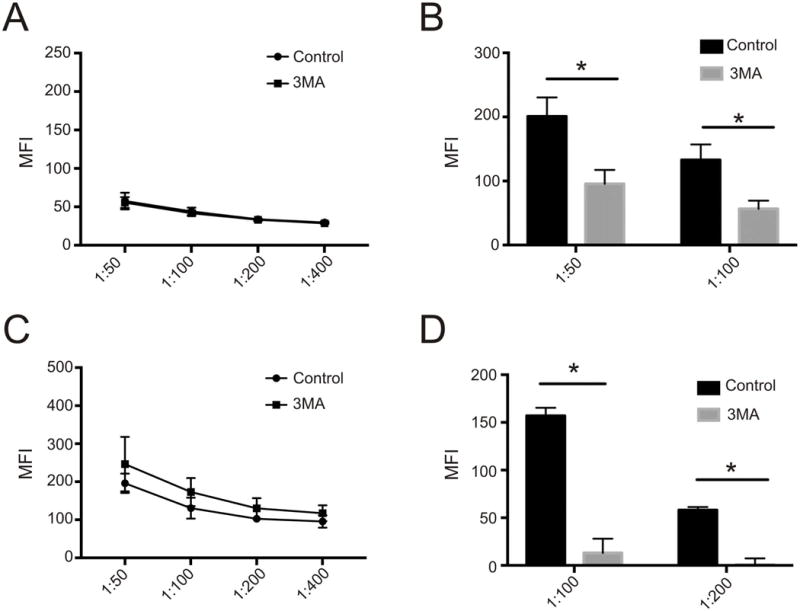

Pharmacological Inhibition of Autophagy Impairs Antibody Recall Response

In an attempt to translate the above findings to a clinically relevant treatment strategy, we tested the effects of 3-methyladenine (3MA), a chemical inhibitor of autophagy that blocks the proximal Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase complex, on induction of secondary alloantibody responses in vivo.25 To verify that 3MA impairs autophagy in vivo, we injected a GFP-LC3 mouse, in which autophagosome formation is indicated by the presence of punctate green fluorescence, with 3MA. When B cells from these mice were compared to control mice, we found significantly fewer cells containing punctate fluorescence in treated mice compared to controls (p<0.01 by Fisher’s Exact Test, repeated three times, data not shown). We then sensitized wild type B6 mice with BALB/c spleen cells as above, and 5 weeks later (at a time when memory B cells have been formed) we treated recipients with 3MA or vehicle every 5 days for 3 weeks. Serum lgG DSA titers did not differ between the groups after sensitization or at the end of the treatment period (although titers were lower at 8 weeks than 5 weeks in both groups, Figure 5A). We then challenged the animals with injections of BALB/c spleen cells and analyzed serum DSA 5 days later. These assays showed significantly lower changes of IgG DSA in the 3MA-treated mice (Figure 5B). Quantification by ELISPOT also showed fewer splenic allospecific ASCs in 3MA-treated mice compared to controls (data not shown). We repeated this experiment in mice sensitized similarly but treated with 3MA for three weeks beginning ten months after sensitization. Pre-challenge titers did not differ between treated and control groups (Figure 5C) but increases in post-challenge antibody production were again impaired in the treated group (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Effect of Autophagy Inhibitor 3-Methyladenine on Secondary Alloantibody Responses (A) Relative binding in diluted serum from treatment and control mice at 8 weeks (after 3 weeks of 3MA administration in the treatment group) after sensitization (n=4 mice in each group). (B) Pre to post-challenge changes in relative binding for 3MA and control treated mice after secondary challenge with i.p. injection of 15×106 donor spleen cells (*p<0.05 3MA vs controls, n=4 mice in each group from one experiment). (C) Relative binding in diluted serum from control and treated mice 10 months after sensitization (including 3 weeks of 3MA administration in the treatment group) along with the corresponding pre to post-challenge changes in relative binding after secondary challenge with 15×106 spleen cells (*p<0.05 3MA vs controls n= 4 in the 3MA group and 2 in the control group)

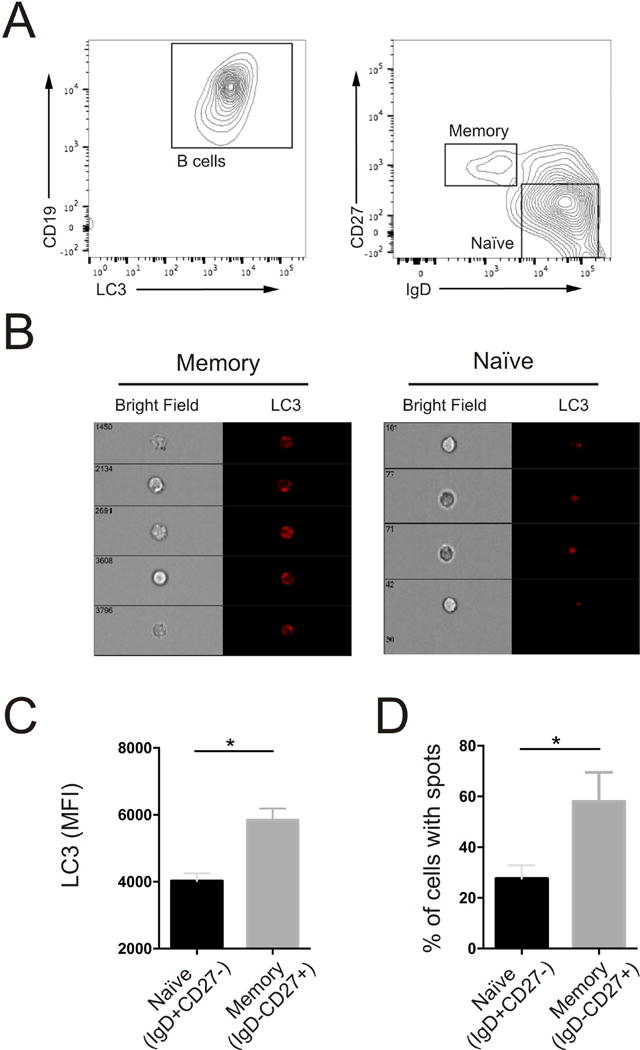

Increased Autophagy in Human Memory B Cells

Finally, in an effort to translate the findings to humans, we quantified autophagy in CD19+CD27+IgD− Bmem26 vs. CD19+CD27-IgD+ naïve B cells from buffy coats obtained from normal volunteers (Fig 6A) Image flow analysis (Figure 6B) demonstrated increased LC3 abundance and increased percentage of autophagosome containing cells (Figure 6 C,D) in Bmem compared to naïve B cells.

Figure 6.

Quantification of Autophagy in Human Memory B cells. (A)Representaive contour plots identifying CD19 positive B cells (left), IgDneg,CD27+ (memory), and IgD+CD27neg (naïve) B cells (right graph). (B) Representative bright field and fluorescent images from memory and naïve B cells. (C) Quantification of intracellular LC3 MFI in and (D) percentage of cells containing fluorescent puncta in memory and naïve B cells. (For C and D, *= p<0.05 and represents data from four separate donors)

Discussion

Our findings add to a growing body of work demonstrating the particular importance of autophagy in immune cell memory14, 27, 28 in several ways. Our work is the first to address the effect of autophagy on immunological B cell memory in transplantation. The AID-CreERT2-eYFP mice permitted us to identify YFP+ B cells that underwent GC reactions following the initial alloimmune stimulus and that persisted up to one year later. This fate-mapping approach defined and identified Bmem (class-switched and persisting for months after GC reaction), circumventing less reliable identification based on cell surface marker phenotyping. We confirmed that YFP+ B cells were enriched for class-switched IgG+anti-H-2Kd allospecific cells (Figure 1).

We next leveraged this system to extend work by others,14,29 using a distinct methodology, demonstrating that autophagy is preferentially more active within Bmem. Our imaging flow analysis of LC3-stained B cells corroborates the seminal findings first observed in infectious and model antigen systems.14,29 The scarcity of allospecific Bmem and difficulty in identifying them compared to those resulting from model antigen sensitization (i.e. NP-KLH) prevented us from definitively identifying increased autophagy within allospecific Bmem. However, when taken in the context of published data on autophagy-dependent Bmem responses to other stimuli and given the demonstrated enrichment of allospecific cells in the YFP+ subset (Figure 1), we provide compelling data supporting that autophagy is increased in allospecific Bmem.

We also provide new evidence that B cell intrinsic autophagy is required for secondary alloantibody responses (Figure 4). Recall alloantibody responses initiated by injection of allogeneic spleen cells or by a heart allograft, and quantified prior to de novo GC reactions30 revealed strikingly fewer alloreactive IgG ASCs and impaired production of IgG DSA in CD19Cre+ × ATG7fl/fl mice indicating that B cell intrinsic autophagy is required for the function and/or survival of alloreactive Bmem. Oxidative stress from dysfunctional mitochondria accumulates with age, is exacerbated in the absence of autophagy31, and could explain decreased survival in autophagy deficient Bmem. In support of this, previous work has shown that treatment of autophagy deficient pathogen-specific Bmem with free radical scavengers (e.g. N-acetylcysteine) partially rescues survival.14 While our data cannot differentiate Bmem function vs. survival we speculate, based on the work of Chen et al., that B cell intrinsic autophagy primarily mediates survival of long-lived Bmem. In contrast to its effect on secondary responses, and consistent with work performed in anti-viral immunity using the same murine model29 our data show that absent B cell autophagy does not affect primary alloantibody responses. Our results differ somewhat from published work that showed decreased primary antibody responses in CD19CreXATG5fl/fl mice.32 The published work was performed in a different system (ATG5 deficient mice). We speculate that the findings in the ATG5 deficient mice differ from our results (and those of Chen et al.) because of autophagy-independent ATG5 effects that have been documented in other systems.33 Finally, the short life span of naïve B cells (days to weeks)34 may also explain why autophagy is dispensable in this group. Conversely Bmem, detected decades after their generation, have an indefinite lifespan with increased dependence on autophagy for survival.35

An additional new observation of clinical relevance is that pharmacological inhibition of autophagy using 3MA mitigated secondary alloantibody formation even when treatment was initiated 10 month after the sensitizing stimulus (Fig 5C–D). 3MA does have documented autophagy-independent effects: e.g. its use in immune cells is associated with altered innate immunity and intracellular signal transduction pathways.36 Several other candidate autophagy inhibitors exist but, similar to 3MA, indirectly inhibit autophagy.37 Ideal pharmacological agents would affect the autophagy pathway more specifically.

Lastly, we show for the first time that autophagy is increased in human Bmem. A sensitized kidney transplant recipient can harbor anti-donor Bmem that exist in the absence of DSA but are capable of differentiating into alloreactive antibody secreting cells.3 Our observation in human Bmem together with the murine data support the need to test whether inhibiting B cell autophagy could selectively inhibit secondary alloantibody responses in sensitized individuals.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates an essential role for autophagy in the function and/or survival of Bmem in the context of transplantation. Together, the findings delineate B cell autophagy as a previously unrecognized therapeutic target for preventing DSA production and associated allograft injury in sensitized transplant candidates.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Representative B cell ELISPOT of sorted B220+, YFP+/YFPneg B cells from AID-CreERT2-eYFP mice after tamoxifen alone (naïve) or after sensitizing with BALB/c splenocytes one week prior to tamoxifen induction. B cells (5×103 for IgG assay, 2×104 for H-2Kd assay) were assayed for the presence of IgG producing and H-2Kd alloreactive antibody producing cells. IgG producing cells were found in both YFP+ subsets, antibody secreting cells against H-2Kd were detected only in cells from sensitized mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anita Chong and Jianjun Chen for their advice on dual-tetramer staining. The authors thank Jean-Claude Weill and Claude-Agnes Reynaud for use of the AID-CreERT2-eYFP mouse model. The authors acknowledge the NIH Tetramer core facility at Emory University for providing the monomers used in this work. The maintenance of the Image Flow Cytometer was supported by the Modeling Immunity for Biodefense program U19AI117873-02 and the Dean’s Office of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

JL is supported by an NIH/NIDDK K08 DK090217, PSH is supported by an NIH R01 AI 071185 (PSH), and MF is supported by NIH T32 AI078892.

Abbreviations

- 3MA

3-methyladenine

- AID

Activation Induced Cytidine Deaminase

- ASC

antibody secreting cell

- ATG

Autophagy Related Gene

- BCR

B cell receptor

- Bmem

memory B cell

- DSA

donor specific antibody

- DST

donor specific transfusion

- ELISPOT

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent spot

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- GC

germinal center

- LC3

microtubule associated protein light chain 3

- MHC

major histocompatibility molecule

- PC

plasma cells

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, et al. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Hill GS, et al. Preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies predict outcome in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1398–1406. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009101065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lúcia M, Luque S, Crespo E, et al. Preformed circulating HLA-specific memory B cells predict high risk of humoral rejection in kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2015;88:874–887. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306:990–995. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuma A, Mizushima N, Ishihara N, et al. Formation of the approximately 350-kDa Apg12-Apg5.Apg16 multimeric complex, mediated by Apg16 oligomerization, is essential for autophagy in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18619–18625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirisako T, Baba M, Ishihara N, et al. Formation process of autophagosome is traced with Apg8/Aut7p in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:435–446. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition) Autophagy. 2016;12:1–222. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan H, Perry CN, Huang C, et al. LPS-induced autophagy is mediated by oxidative signaling in cardiomyocytes and is associated with cytoprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H470–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01051.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gade P, Ramachandran G, Maachani UB, et al. An IFN-γ-stimulated ATF6-C/EBP-β-signaling pathway critical for the expression of Death Associated Protein Kinase 1 and induction of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10316–10321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119273109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawakami T, Inagi R, Takano H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces autophagy in renal proximal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2665–2672. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado MA, Elmaoued RA, Davis AS, et al. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M, Hong MJ, Sun H, et al. Essential role for autophagy in the maintenance of immunological memory against influenza infection. Nat Med. 2014;20:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nm.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dogan I, Bertocci B, Vilmont V, et al. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, et al. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1101–1111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavzy SJ, Heeger PS. Effect of Absent Immune Cell Expression of Vitamin D Receptor on Cardiac Allograft Survival in Mice. Transplantation. 2015;99:1365–1371. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leventhal JS, Ni J, Osmond M, et al. Autophagy Limits Endotoxemic Acute Kidney Injury and Alters Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Cytokine Expression. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cravedi P, Leventhal J, Lakhani P, et al. Immune cell-derived C3a and C5a costimulate human T cell alloimmunity. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2530–2539. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decaluwe H, Taillardet M, Corcuff E, et al. Gamma(c) deficiency precludes CD8+ T cell memory despite formation of potent T cell effectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9311–9316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913729107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Yin H, Xu J, et al. Reversing endogenous alloreactive B cell GC responses with anti-CD154 or CTLA-4Ig. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2280–2292. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomayko MM, Steinel NC, Anderson SM, et al. Cutting edge: Hierarchy of maturity of murine memory B cell subsets. J Immunol. 2010;185:7146–7150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuccarino-Catania GV, Sadanand S, Weisel FJ, et al. CD80 and PD-L2 define functionally distinct memory B cell subsets that are independent of antibody isotype. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:631–637. doi: 10.1038/ni.2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. 3-Methyladenine: specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:1889–1892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein U, Rajewsky K, Küppers R. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of human peripheral blood B-cell subsets with special reference to N-region addition and J kappa-usage in V kappa J kappa-joints and kappa/lambda-ratios in naive versus memory B-cell subsets to identify traces of receptor editing processes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1999;246:141–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60162-0_18. discussion 147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salio M, Puleston DJ, Mathan TS, et al. Essential role for autophagy during invariant NKT cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E5678–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413935112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlie K, Westerback A, DeVorkin L, et al. Survival of effector CD8+ T cells during influenza infection is dependent on autophagy. J Immunol. 2015;194:4277–4286. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen M, Kodali S, Jang A, et al. Requirement for autophagy in the long-term persistence but not initial formation of memory B cells. J Immunol. 2015;194:2607–2615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Wang Q, Yin D, et al. Cutting Edge: CTLA-4Ig Inhibits Memory B Cell Responses and Promotes Allograft Survival in Sensitized Recipients. J Immunol. 2015;195:4069–4073. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.García-Prat L, Martínez-Vicente M, Perdiguero E, et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature. 2016;529:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature16187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pengo N, Scolari M, Oliva L, et al. Plasma cells require autophagy for sustainable immunoglobulin production. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:298–305. doi: 10.1038/ni.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimmey JM, Huynh JP, Weiss LA, et al. Unique role for ATG5 in neutrophil-mediated immunopathology during M. tuberculosis infection. Nature. 2015;528:565–569. doi: 10.1038/nature16451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fulcher DA, Basten A. B cell life span: a review. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997;75:446–455. doi: 10.1038/icb.1997.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu X, Tsibane T, McGraw PA, et al. Neutralizing antibodies derived from the B cells of 1918 influenza pandemic survivors. Nature. 2008;455:532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature07231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crisan TO, Plantinga TS, van de Veerdonk FL, et al. Inflammasome-independent modulation of cytokine response by autophagy in human cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Xia HG, Yuan J. Pharmacologic agents targeting autophagy. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:5–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI73937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Representative B cell ELISPOT of sorted B220+, YFP+/YFPneg B cells from AID-CreERT2-eYFP mice after tamoxifen alone (naïve) or after sensitizing with BALB/c splenocytes one week prior to tamoxifen induction. B cells (5×103 for IgG assay, 2×104 for H-2Kd assay) were assayed for the presence of IgG producing and H-2Kd alloreactive antibody producing cells. IgG producing cells were found in both YFP+ subsets, antibody secreting cells against H-2Kd were detected only in cells from sensitized mice.