Abstract

Background

Dyspnoea consists of multiple dimensions including the intensity, unpleasantness, sensory qualities and emotional responses which may differ between patient groups, settings and in relation to treatment. The Dyspnoea-12 is a validated and convenient instrument for multidimensional measurement in English. We aimed to take forward a Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12.

Methods

The linguistic validation of the Dyspnoea-12 was performed (Mapi Language Services, Lyon, France). The standardised procedure involved forward and backward translations by three independent certified translators and revisions after feedback from an in-country linguistic consultant, the developerand three native physicians. The understanding and convenience of the translated version was evaluated using qualitative in-depth interviews with five patients with dyspnoea.

Results

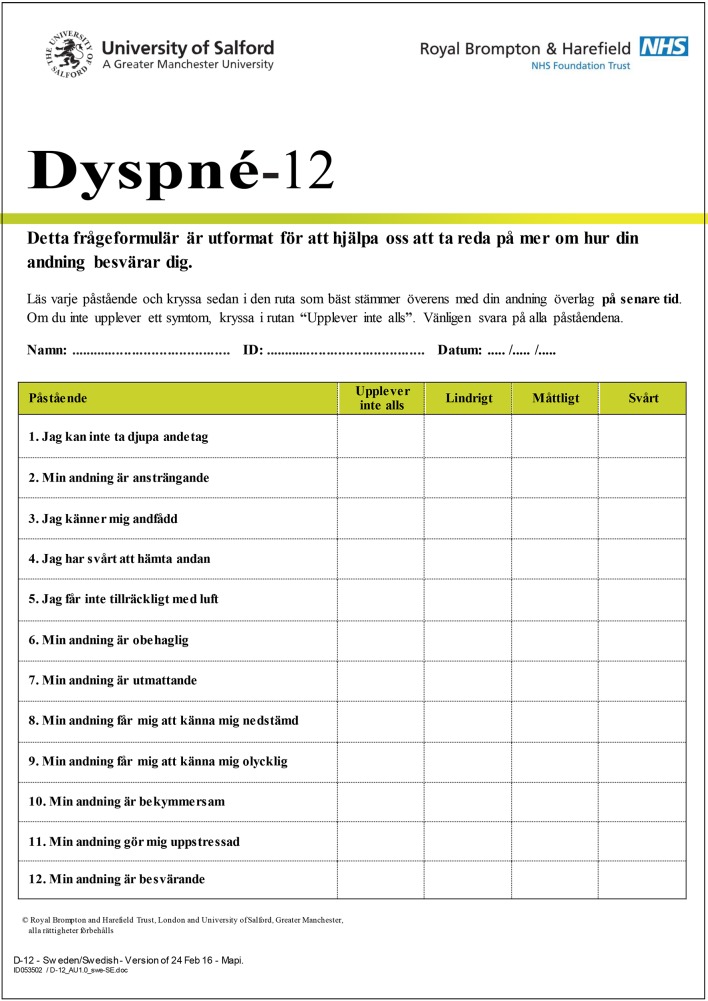

A Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12 was elaborated and evaluated carefully according to international guidelines. The Swedish version, ‘Dyspné−12’, has the same layout as the original version, including 12 items distributed on seven physical and five affective items. The Dyspnoea-12 is copyrighted by the developer but can be used free of charge after permission for not industry-funded research.

Conclusion

A Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12 is now available for clinical validation and multidimensional measurement across diseases and settings with the aim of improved evaluation and management of dyspnoea.

Keywords: dyspnoea, multidimensional, measurement, Swedish, translation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The linguistic validation of the Dyspnoea-12 to Swedish was performed using a structured multistage process in accordance with international guidelines, involving translations by two independent certified translators, a backward translation for quality check and review by clinicians and test on patients with dyspnoea before establishing the final Swedish version.

A Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12 will enable to conduct clinical validation studies across patient populations and settings, and will bring a new possibility to deepen the understanding of breathlessness and to value the impact of different dimensions of breathlessness.

The translated version of the Dyspnoea-12 still needs to be psychometrically validated in a clinical Swedish population.

Introduction

Reduction of symptoms is a major treatment goal in chronic cardiac and respiratory diseases. Dyspnoea is the cardinal symptom in cardiopulmonary diseases, including heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial lung diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Dyspnoea is strongly associated with impaired health-related quality of life in COPD1 and IPF,2 and with increased mortality in COPD,3 4 IPF5 6 and heart failure.7 Despite this fact, clinical practice often focuses on underlying diseases and not on the management of the often chronic symptom of dyspnoea itself.8

Multiple dimensions of dyspnoea

Traditionally, dyspnoea has been assessed as an indirect measure of functional limitation due to breathlessness, as with the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale,9 or using a single rating scale such as a visual analogue scale (VAS)10 or Borg scale11 during exercise tests. However, growing attention has been paid to the fact that dyspnoea consists of multiple important dimensions besides the overall intensity or unpleasantness, such as sensory and affective qualities, associated emotional responses and the functional impact on the person´s life.12 This makes it difficult to compare findings between patient populations and between differences in responses of separate treatments of dyspnoea.13 Thus, standardised measurements with different dimensions of dyspnoea are needed.

Dyspnoea-12

The Dyspnoea-12 instrument was developed to be a concise instrument for quantification of different aspects of dyspnoea, valid across different cardiorespiratory diseases.14 In the original study establishing the final version of the Dyspnoea-12, the instrument was associated with the MRC scale in COPD, IPF and heart failure.14 The subsequent validation study showed a good internal reliability and test–retest reliability, and the Dyspnoea-12 was significantly correlated to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the MRC scale, the forced expiratory volume in 1 s and the 6 min walking distance test.14 After the initial validation, further studies have validated the use of the Dyspnoea-12 in interstitial lung disease15 and COPD,16 but also in asthma,17 pulmonary arterial hypertension,18 bronchiectasis and tuberculosis destroyed lungs.19

The Dyspnoea-12 is available in English,14 Arabic16 20 and Korean,19 but has to our knowledge not been translated into any other European language except English. A multidimensional instrument for assessment of dyspnoea in cancer, the Cancer Dyspnoea Scale, has been developed21 and validated in Swedish,22 and recently the Multidimensional Dyspnoea Profile13 has been linguistically validated in Swedish.23 However, a brief and convenient multidimensional instrument that allows comparison across diseases would be of additional value. Until now, there has been no multidimensional instrument for measurement of dyspnoea available in Swedish. A Swedish version of Dyspnoea-12 should be of great importance for further research in the field of breathlessness, especially to be able to make comparisons across populations. We therefore aimed to develop a linguistically validated Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12.

Methods

The Dyspnoea-12 instrument

The Dyspnoea-12 instrument includes 12 descriptors assessed on a 4-point scale such as none (score 0), mild (score 1), moderate (score 2), or severe (score 3), resulting in a total score from 0 to 36 where a higher score corresponds to more severe breathlessness. The first seven items constitute a physical domain assessing whether the breath does not go in all the way, the patient cannot get enough air, feels short of breath or has difficulty catching breath, and the breathing requires more work, is uncomfortable or exhausting. The remaining five items constitute an emotional domain where the items describe whether the breathing is distressing, irritating or makes the patient feel depressed, miserable or agitated. A physical and an emotional component score can be calculated, with maximum score of 21 and 15, respectively. A minimal important clinical difference of three units has been recommended.24

Linguistic validation

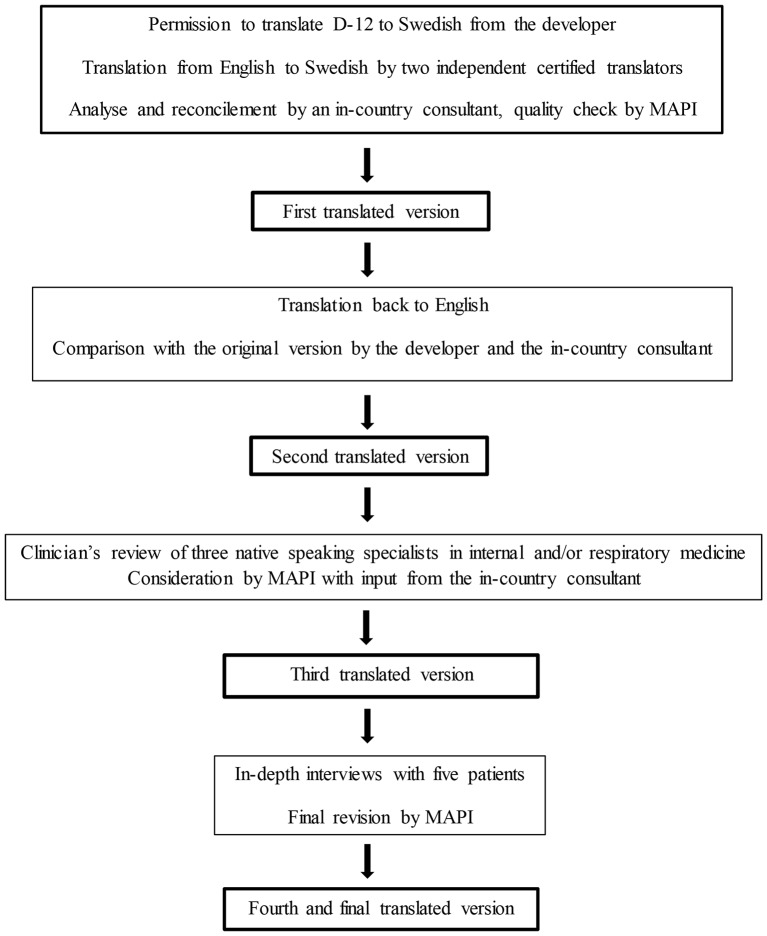

The linguistic validation of the Dyspnoea-12 into Swedish was performed in a structured multistage process in accordance with international guidelines,25 26 in collaboration with a company specialised in translation and validation of patient-reported outcome measures (Mapi Language Services, Lyon, France; hereafter referred to as ‘Mapi’).27 Permission to translate the Dyspnoea-12 into Swedish was obtained from the developer. The role of Mapi was to supply translators and to perform quality checks in collaboration with the developer. The whole process is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the linguistic validation process.

Translation

Two independent certified translators, native speakers of Swedish and living in Sweden, translated the original instrument developed in British English into Swedish. These two forward translations were analysed and reconciled by an in-country consultant into a first translated version. After a quality check from Mapi, the first Swedish version was translated back into English and compared with the original British version by the developer and by the in-country consultant, to establish a second translated Swedish version.

Clinicians’ review

The second translated version was reviewed by three native Swedish-speaking specialists in internal and/or respiratory medicine, including the authors of this paper, to provide detailed feedback on the wordings from a clinical perspective. The feedback from the clinicians was considered by Mapi again with input from the in-country consultant and the developer, resulting in a third translated Swedish version.

Patients’ interviews

The third translated version was evaluated using a validated method of individual in-depth interviews27 with five Swedish patients with dyspnoea, recruited by Mapi and the in-country consultant, to investigate if the instrument was easy to understand, assimilate and accept. The patients were selected by convenience. No patients denied participating. Data saturation was not discussed, as the number of patients were decided according to Mapi’s guidelines on linguistic validation. Two of the patients were males and three females, and their main conditions were asthma, heat failure or anxiety disorder. The patients were interviewed face-to-face by the local consultant, and the interviews took place at the consultant´s office during 7–10August 2015. The consultant was female, her occupation was physiotherapist and she had 20 years of experience of patient interviews. The consultant had no personal relationship to the patients and no bias to report to the patients before the interviews. No one else except the consultant and the patient were present during the interviews. The patients were asked to complete the questionnaire and subsequently make general comments and answer two specific questions for each item. They were told that the intention was to assess whether the questionnaire was comprehensible and acceptable for them, but not to evaluate their answers to the items. The first question was “What does the instructions/question/response choice mean for you?”, and encouraged the respondents to reword the item using other words that those used or to give examples. The second question was “Did you have difficulty understanding the instructions/question/response choice?” and also included follow-up questions if there were words that were difficult to understand and suggested changes of the wording. The patients were encouraged to speak and to express their feelings about the questions without being interrupted. The consultant was attentive to any non-verbal or verbal signs betraying the way the respondents felt. The interviews took approximately 1 hour each, and were transcribed verbatim. Notes were made by hand in Swedish and translated to English after the interviews. No audio recording was used. The transcripts of the interviews were not returned to the patients and the interviews were not repeated. The feedback from the patients on their understanding and suggested alternative formulations for each item was used for revision and establishment of the final linguistically validated translation. As the purpose of the interviews was only to test the understanding of the Swedish version of Dyspnoea-12, the results of the interviews were not coded or presented in themes or using quotations. The questions used in the interviews were pilot tested in the original English version.

Ethics

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee at Lund University (DNr: 2016/16). Written informed consent for the translation process and clinicians’ review was not required as no personal data on participants were collected. Oral consent was received from the five patients for the in-depth interviews.

Results

The final certified, linguistically validated Swedish translation of the Dyspnoea-12 is found in figure 2. The Swedish version, ‘Dyspné−12’, has the same layout as the original version, including 12 items. The clinicians review resulted in several small linguistic adjustments, after which the instrument was conceptually equivalent to the original but uses the corresponding adequate clinical words and expressions in Swedish. The in-depth interviews with five patients did not result in any further changes. The time period of measurement in the original version is ‘these days’, which was translated into a corresponding word in Swedish.

Figure 2.

Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12.

Discussion

The purpose of this project was to linguistically validate a Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12 instrument. The procedure was performed according to international guidelines for patient-reported outcomes and have resulted in a convenient instrument for the quantification of different aspects of breathlessness in Swedish research. The instrument could be used as a brief and easy-to use alternative or complement to the instrument Multi-Dimensional Profile.13 28

A major strength of our study was the structured multistage process in accordance with international guidelines, including translation by two independent certified translators, backward translation for quality check and clinicians’ and patients’ evaluations before establishing the final translation. Moreover, the Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12 will enable the comparison and aggregation of results from different populations and countries and the development of further research needed to value the impact of different dimensions of breathlessness.

A limitation of the study is that the evaluation of the translated instrument was limited to a smaller number of clinicians and patients. The linguistic validation was performed in accordance with international guidelines, but we cannot exclude the possibility that an evaluation in a larger population could have identified a need to change some of the wordings in the Swedish translation. However, the aim of the present evaluation was to explore if the wordings were comprehensible, not to validate the wordings per se. The translated version of the Dyspnoea-12 also needs to be psychometrically validated in a clinical Swedish population. In addition, linguistic validations in other languages would be of value and much welcome to develop multinational research.

Use of the Dyspnoea-12

The developer of the Dyspnoea-12 recommends that the instrument should not be used with more than three missing items. The idea is to get a general perception of the current state, and thus the term ‘these days’ is suggested. However, the English version of the Dyspnoea-12 has been used with a recall period of ‘the recent 2 weeks’,29 and the Swedish version also need to be validated for different periods of time. The Dyspnoea-12 is copyrighted by the developers but can be used free of charge for not industry-funded research after permission.

Conclusion

A Swedish version of the Dyspnoea-12 is now available for clinical validation and multidimensional measurement across diseases and settings with the aim of improved evaluation and management of dyspnoea.

bmjopen-2016-014490supp001.pdf (490.7KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bengt Dahlander, MD, Capio ASIH Nacka, who contributed to the clinical review of the Dyspnoea-12.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: ME. First draft: JS. Participated in the translation and validation, revision for important intellectual content and approval of the version to be published: JS and ME.

Funding: The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation 1 (Nr 20150424).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The regional ethics committee at Lund University, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, et al. . Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:581–6. 10.1136/thx.54.7.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, et al. . Health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. What is the main contributing factor? Respir Med 2005;99:408–14. 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, et al. . Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest 2002;121:1434–40. 10.1378/chest.121.5.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Casanova C, Marin JM, Martinez-Gonzalez C, et al. . Differential effect of mMRC dyspnea, CAT and CCQ for symptom evaluation within the new GOLD staging and mortality in COPD. Chest 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mura M, Porretta MA, Bargagli E, et al. . Predicting survival in newly diagnosed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a 3-year prospective study. Eur Respir J 2012;40:101–9. 10.1183/09031936.00106011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, et al. . A simple assessment of dyspnoea as a prognostic Indicator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1067–72. 10.1183/09031936.00152609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ekman I, Cleland JG, Swedberg K, et al. . Symptoms in patients with heart failure are prognostic predictors: insights from COMET. J Card Fail 2005;11:288–92. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson MJ, Currow DC, Booth S. Prevalence and assessment of breathlessness in the clinical setting. Expert Rev Respir Med 2014;8:151–61. 10.1586/17476348.2014.879530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988;93:580–6. 10.1378/chest.93.3.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lansing RW, Moosavi SH, Banzett RB. Measurement of dyspnea: word labeled visual analog scale vs. verbal ordinal scale. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2003;134:77–83. 10.1016/S1569-9048(02)00211-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982;14:377–81. 10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. . An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:435–52. 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Banzett RB, O'Donnell CR, Guilfoyle TE, et al. . Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile: an instrument for clinical and laboratory research. Eur Respir J 2015;45:1681–91. 10.1183/09031936.00038914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yorke J, Moosavi SH, Shuldham C, et al. . Quantification of dyspnoea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the Dyspnoea-12. Thorax 2010;65:21–6. 10.1136/thx.2009.118521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yorke J, Swigris J, Russell AM, et al. . Dyspnea-12 is a valid and reliable measure of breathlessness in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest 2011;139:159–64. 10.1378/chest.10-0693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alyami MM, Jenkins SC, Lababidi H, et al. . Reliability and validity of an arabic version of the dyspnea-12 questionnaire for Saudi nationals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Thorac Med 2015;10:112–7. 10.4103/1817-1737.150730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yorke J, Russell AM, Swigris J, et al. . Assessment of dyspnea in asthma: validation of the Dyspnea-12. J Asthma 2011;48:602–8. 10.3109/02770903.2011.585412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yorke J, Armstrong I. The assessment of breathlessness in pulmonary arterial hypertension: reliability and validity of the Dyspnoea-12. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014;13:506–14. 10.1177/1474515113514891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee BY, Lee S, Lee JS, et al. . Validity and reliability of CAT and Dyspnea-12 in Bronchiectasis and tuberculous destroyed lung. Tuberc Respir Dis 2012;72:467–74. 10.4046/trd.2012.72.6.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al-Gamal E, Yorke J, Al-Shwaiyat MK. Dyspnea-12-Arabic: testing of an instrument to measure breathlessness in arabic patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 2014;43:244–8. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, et al. . Development and validation of the Cancer Dyspnoea Scale: a multidimensional, brief, self-rating scale. Br J Cancer 2000;82:800–5. 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henoch I, Bergman B, Gaston-Johansson F. Validation of a Swedish version of the Cancer Dyspnea Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:353–61. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ekström M, Sundh J. Swedish translation and linguistic validation of the multidimensional dyspnoea profile. Eur Clin Respir J 2016;3:32665 10.3402/ecrj.v3.32665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yorke J, Lloyd-Williams M, Smith J, et al. . Management of the respiratory distress symptom cluster in lung Cancer: a randomised controlled feasibility trial. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:3373–84. 10.1007/s00520-015-2810-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. . Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for Patient-Reported outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005;8:94–104. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wild D, Eremenco S, Mear I, et al. . Multinational trials-recommendations on the translations required, approaches to using the same language in different countries, and the approaches to support pooling the data: the ISPOR Patient-Reported Outcomes Translation and Linguistic Validation Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health 2009;12:430–40. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mapigroup 2016. http://mapigroup.com/.

- 28. Morélot-Panzini C, Gilet H, Aguilaniu B, et al. . Real-life assessment of the multidimensional nature of dyspnoea in COPD outpatients. Eur Respir J 2016;47:1668–79. 10.1183/13993003.01998-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams MT, John D, Frith P. Comparison of the Dyspnoea-12 and Multidimensional Dyspnoea Profile in people with COPD. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1600773 10.1183/13993003.00773-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014490supp001.pdf (490.7KB, pdf)