Abstract

Objectives

Beta blockers reduce mortality in heart failure (HF). However, it is not clear whether they should be temporarily withdrawn during acute HF.

Design

Analysis of prospectively collected data.

Setting

The Gulf aCute heArt failuRe rEgistry is a prospective multicentre study of patients hospitalised with acute HF in seven Middle Eastern countries.

Participants

5005 patients with acute HF.

Outcome measures

We studied the effect of beta blockers non-withdrawal on intrahospital, 3-month and 12-month mortality and rehospitalisation for HF in patients with acute decompensated chronic heart failure (ADCHF) and acute de novo heart failure (ADNHF) and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%.

Results

44.1% of patients were already on beta blockers on inclusion. Among those, 57.8% had an LVEF <40%. Further, 79.9% were diagnosed with ADCHF and 20.4% with ADNHF. Mean age was 61 (SD 13.9) in the ADCHF group and 59.8 (SD 13.8) in the ADNHF group. Intrahospital mortality was lower in patients whose beta blocker therapy was not withdrawn in both the ADCHF and ADNHF groups. This protective effect persisted after multivariate analysis (OR 0.05, 95% CI 0.022 to 0.112; OR 0.018, 95% CI 0.003 to 0.122, respectively, p<0.001 for both) and propensity score matching even after correcting for variables that remained significant in the new model (OR 0.084, 95% CI 0.015 to 0.468, p=0.005; OR 0.047, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.169, p<0.001, respectively). At 3 months, mortality was still lower only in patients with ADCHF in whom beta blockers were maintained during initial hospitalisation. However, the benefit was lost after correcting for confounding factors. Interestingly, rehospitalisation for HF and length of hospital stay were unaffected by beta blockers discontinuation in all patients.

Conclusion

In summary, non-withdrawal of beta blockers in acute decompensated chronic and de novo heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with lower intrahospital mortality but does not influence 3-month and 12-month mortality, rehospitalisation for heart failure, and the length of hospital stay.

Trial registration number

NCT01467973; Post-results.

Keywords: heart failure, adult cardiology, cardiac epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess non-withdrawal of beta blockers in de novo heart failure.

Like any observational study, selection bias could exist. Moreover, the decision of beta blocker withdrawal during acute heart failure could have been due to different factors that we did not account for in our analysis.

Furthermore, no information was available regarding the dose of beta blockers, in particular whether the dose was reduced in patients who continued to use beta blockers during acute decompensation.

Introduction

Since the publication of the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure, the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol study II (CIBIS-II,) the US Carvedilol Heart failure and the Carvedilol Prospective Cumulative Survival Study (COPERNICUS) trials,1–4 in which beta blockers improved survival in patients with heart failure (HF), international guidelines recommended using this drug class as first-line treatment in chronic HF along with the renin-angiotensin system blockers.5 Initial safety concerns regarding the use of beta blockers in patients with HF were dropped with the emergence of several studies that demonstrated up to 30% decrease in mortality risk in those patients.6 Despite the improvement in the treatment and prognosis of chronic HF, acute HF remains a challenging condition, treatment of which is essentially symptomatic. In the EuroHeart Failure Survey II, in-hospital mortality of patients with acute HF was about 7%,7 and 1-year mortality above was 20%.8 The continuation of beta blockers during acute HF remains controversial and subject to clinical judgement. The Beta-blocker CONtinuation Versus INterruption in patients with Congestive heart failure hospitalizED for a decompensation episode (B-CONVINCED) trial, a randomised, controlled, open-labelled study that compared continuation with withdrawal of beta blockers during acute HF did not report any short-term or long-term benefit in patients assigned to continue their treatment.9 In a post hoc analysis of the Survival of Patients With Acute Heart Failure in Need of Intravenous Inotropic Support (SURVIVE) study that had a similar design to B-CONVINCED, 1-month and 3-month mortality decreased in patients whose beta blockers were not withdrawn during initial hospitalisation.10 However, the protective effect was lost after correcting for classical heart failure covariates.

Currently, there is no large-scale data from the Middle East (ME) with regard to beta blockers use in HF. The aim of this paper is to report on use of beta blockers in patients admitted with acute HF and to assess short-term and long-term consequences of withdrawal or continuation of beta blockers in patients with HF with left ventricular dysfunction in the ME.

Methods

The Gulf aCute heArt failuRe registry (Gulf-CARE) is a multinational multicentre prospective observational acute heart failure survey based on cases admitted to various hospitals in seven countries from the Gulf Middle East, namely Oman, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Bahrain, Yemen and Kuwait. Details of the recruitment of patients, the study design and methods have been published previously.11 12 In brief, we collected data, as per the case report form, of patients with acute HF from both genders who were above 18 years of age admitted to the participating hospitals. Recruitment started in February 2012 and ended on 13 November 2012. This was preceded by a pilot phase of 1 month in November 2011. The registry continued to follow-up patients at 3 months and 1 year. The registry protocol was approved by each participating centre’s research ethics committee or institutional review board (IRB): Directorate of research and studies, Ministry of Health—Sultanate of Oman, King Saud University’s IRB, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Sheikh Khalifa medical city’s IRB, UAE, Hamad Medical Corporation’s IRB, Qatar, Mohammed Bin Khalifa cardiac centre’s IRB, Bahrain, Sana'a University’ IRB, Yemen and Ministry of Health’s IRB in Kuwait. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov with number NCT01467973. A written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Acute HF was further classified as either acute decompensated chronic heart failure (ADCHF) or acute de novo heart failure (ADNHF). ADCHF was defined as worsening of HF in patients with a previous diagnosis or hospitalisation for HF. ADNHF was defined as acute HF in patients with no prior history of heart failure. All patients were followed-up at 3 months by telephone, and at 1 year either by telephone or by a clinic visit. The registry data were collected online using a dedicated website including demographics, risk factors, medical history, clinical manifestations, investigations, medications with dose and management. The participating hospitals ranged from secondary care hospitals to tertiary care hospitals with interventional facilities including device therapy.

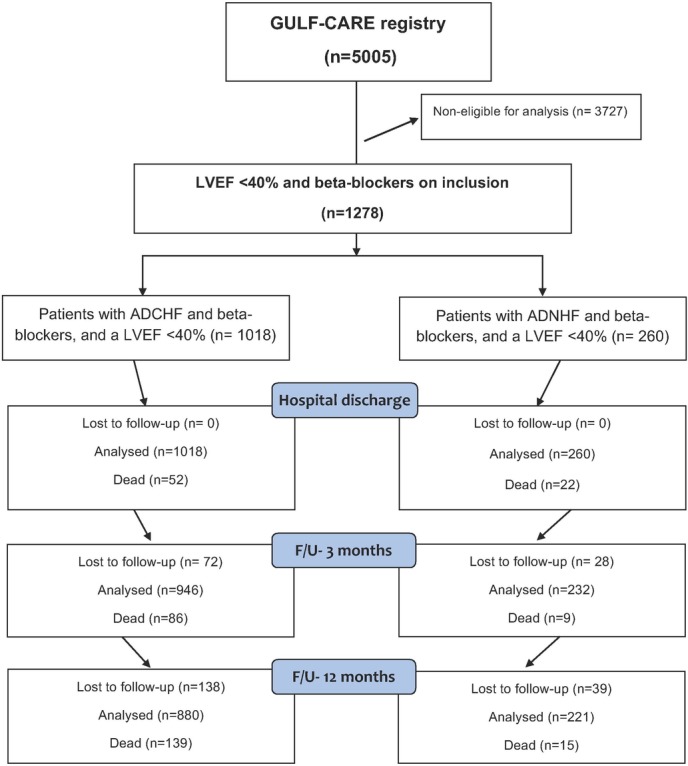

The inclusion criteria for this analysis was those patients who were on beta blockers at time of admission and had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%. Those patients with preserved left ventricular function and not on beta blockers at time of admission were excluded from further analysis. Furthermore, two cohorts were created, the first with ADCHF and the second with ADNHF. The main outcome measures were mortality, re-hospitalisation for HF and length of hospital stay. A scheme of the current prospective trial is described in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the current prospective analysis. Analysed were 1278 patients with an LVEF <40% and beta blockers on admission from the 5005 participants in the GULF-CARE registry. ADCHF, acute decompensated chronic heart failure; ADNHF, acute de novo heart failure; F/U, follow-up; GULF-CARE, Gulf aCute heArt failuRe rEgistry; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Baseline categorical variables and outcome measures were summarised using frequency distributions whiles means and SD were used for continuous variables. Outcome measures and baseline patients’ characteristics were compared between the two groups: withdrawal and non-withdrawal of beta blockers using the χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts fell below 5) for categorical variables and the student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for numeric variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis performed for in-hospital and 3 months included variables that were significantly different between the two groups in addition to age and gender. The model included age, gender, non-compliance to medication, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), LVEF, creatinine, aspirin, statins and inotropes for ADCHF; and age, gender, ACE inhibitors and inotropes for ADNHF. Adjusted OR and 95% CIs with p values are presented. All analyses were done separately for the patients with ADCHF and ADNHF. In addition, several sensitivity analyses were performed. Propensity scores were computed using logistic regression with membership in the two groups as the outcome and baseline variables that were significantly different between the groups as the independent variables. These scores were used to adjust the association between the mortality outcomes and the main variable (membership in each group) using multivariate logistic regression. Moreover, propensity score matching using the most influential variable (inotropes) was used and the main comparison between the two groups was assessed with and without adjustment to variables that were still significantly different between the two groups even after matching. In ADCHF, variables adjusted after propensity score matching were gender, non-compliance to medication, SBP, DBP, statins and aspirin, whereas in ADNHF we only adjusted for ACE inhibitors as the sample sizes became small after matching. Statistical significance was set at the 5% level (two-tailed test). All analyses were done using IBM-SPSS V.23.0.

Results

Out of the total 5005 participants in the GULF-CARE, 2208 (44.1%) patients were already on beta blockers on inclusion. Further, beta blockers were prescribed in 1278 (42.2%) patients with a LVEF <40%. Among those, 1018 (79.9%) were diagnosed with ADCHF and 260 (20.4%) with ADNHF. As shown in table 1, patients with ADCHF tended to have more comorbidities than patients with ADNHF. They had a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation and a lower LVEF; which could explain the more common use of angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARBs), aldosterone antagonists, vitamin K antagonists and diuretics in these patients. Interestingly, they smoked less, a phenomenon that could be due to the effect of earlier lifestyle changes and antismoking campaigns in patients with CHF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients on beta blockers on admission and a left ventricular ejection fraction <40% included in the Gulf-CARE

| All patients in Gulf CARE n=5005 |

Patients with a LVEF <40% on beta blockers on admission n=1278 |

p Value * | ||

| Patients with ADCHF and a LVEF <40%, on beta blockers on admission n=1018 |

Patients with ADNHF and a LVEF <40% on beta blockers on admission n=260 |

|||

| Age (years) | 59±15 | 61.0±13.9 | 59.8±13.8 | 0.21 |

| Male gender | 3131 (62.6) | 751 (73.8) | 177 (68.1) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28±6 | 27.7±5.8 | 28.1±5.7 | 0.26 |

| Hypertension | 3059 (61.1) | 673 (66.1) | 181 (69.6) | 0.29 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2492 (49.8) | 569 (55.9) | 147 (56.5) | 0.86 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1799 (35.9) | 464 (45.6) | 106 (40.8) | 0.16 |

| Smoking | 1103 (22) | 162 (15.9) | 67 (25.8) | 0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| Arabs | 4516 (90.2) | 937 (92.0) | 232 (89.2) | 0.04 |

| Asians | 473 (9.5) | 77 (7.6) | 28 (10.8) | |

| Others | 16 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) | – | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Known CAD | 2337 (46.7) | 676 (66.4) | 150 (57.7) | 0.008 |

| Stroke/TIAs | 404 (8) | 96 (9.4) | 29 (11.2) | 0.40 |

| Valvular heart disease | 675 (13.5) | 154 (15.1) | 19 (7.3) | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 607 (12) | 170 (16.7) | 23 (8.8) | 0.001 |

| CKD | 744 (14.9) | 215 (21.1) | 28 (10.8) | 0.001 |

| Aetiology | ||||

| Non-compliance to medication | 964 (19) | 300 (29.5) | 40 (15.4) | 0.05 |

| IHD | 1365 (27) | 204 (20.0) | 117 (45.0) | 0.67 |

| HTN | 410 (8.2) | 46 (4.5) | 12 (4.6) | 0.26 |

| Arrhythmia | 301 (6) | 61 (6.0) | 11 (4.2) | 0.49 |

| Anaemia | 143 (3.1) | 23 (2.3) | 5 (1.9) | 0.50 |

| Renal failure | 221 (4.4) | 58 (5.7) | 9 (3.5) | 0.19 |

| Clinical and biochemical parameters | ||||

| HR, bpm | 77.6±12.8 | 94.4±22.4 | 94.6±22.3 | 0.92 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 118±18 | 126.6±30.6 | 133.6±32.4 | 0.002 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 70±12 | 76.4±17.9 | 80.5±19.3 | 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 36.9±14 | 26.6±7.1 | 28.8±7.2 | 0.001 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 5324±4523 | 6847±9679 | 5227±4924 | 0.21 |

| Creatinine, mmol/L | 130±116 | 137.7±116.3 | 128.5±121.9 | 0.24 |

| Medications | ||||

| Carvedilol | 1099 (21.9) | 649 (63.8) | 100 (38.5) | 0.001 |

| Bisoprolol | 626 (12.5) | 286 (28.1) | 90 (34.6) | 0.04 |

| Metoprolol | 299 (5.9) | 64 (6.3) | 35 (13.5) | 0.001 |

| Atenolol | 184 (3.6) | 19 (1.9) | 35 (13.5) | 0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 2762 (55.2) | 652 (64.0) | 166 (63.8) | 0.96 |

| ARBs | 645 (12.9) | 180 (17.7) | 23 (8.8) | 0.001 |

| Statins | 2555 (51) | 751 (73.8) | 180 (69.2) | 0.14 |

| Aspirin | 3089 (61.7) | 832 (81.7) | 204 (78.5) | 0.23 |

| VKA | 618 (12) | 221 (21.7) | 19 (7.3) | 0.001 |

| Ibravadine | 115 (2.3) | 48 (4.7) | 7 (2.7) | 0.15 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 840 (16.8) | 419 (41.2) | 45 (17.3) | 0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 966 (19) | 301 (29.6) | 81 (31.2) | 0.61 |

| Diuretics | 2882 (57.6) | 920 (90.4) | 113 (43.5) | 0.001 |

| Inotropes use during hospitalisation | 783 (16) | 156 (15.3) | 51 (19.6) | 0.96 |

All values are given as n (%) or mean ±SD.

*p Value: patients with acute decompensated chronic heart failure and LVEF <40% on beta blockers on admission versus de novo heart failure and LVEF <40% on beta blockers on admission.

ADCHF, acute decompensated chronic heart failure; ADNHF, acute de novo heart failure; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; CARE, aCute heArt rEgistry; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; IHD, ischemic heart disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TIAs, transient ischaemic attacks; VKA, Vitamin K antagonists.

Beta blockers were withdrawn in 9% of the patients in the ADCHF group and 13.8% in the ADNHF group. Those patients with ADCHF in whom beta blockers were discontinued had a lower blood pressure at inclusion and half of them required inotropic support during hospitalisation (see online supplementary table 1). Patients with ADNHF who continued beta blockade therapy were more commonly prescribed ACE inhibitors and required less inotropic support (see online supplementary table 2).

bmjopen-2016-014915supp001.pdf (95.2KB, pdf)

In the ADCHF group, 15 (1.6%) in-hospital deaths occurred in patients whose beta blocker therapy was not withdrawn as compared with 37 (40.2%) when beta blockers were discontinued (p<0.001) (table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of non-withdrawal of beta blockers in acute decompensated chronic heart failure with beta blocker therapy on admission and a LVEF <40%

| All patients with acute decompensated heart failure, LVEF<40% and on beta-treatment on admission n=1018 |

Beta blockers maintained during hospitalisation n=926 (91%) |

Beta blockers withdrawn during hospitalisation n=92 (9.0%) |

p Value | |

| Inhospital outcome | ||||

| Death | 52/1018 (5.1) | 15/926 (1.6) | 37/92 (40.2%) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) | 9.9±15.0 | 9.7±15.1 | 12.3±13.6 | 0.1 |

| 3-Month follow-up | ||||

| Death | 86/946 (9.1) | 77/896 (8.6) | 9/50 (18.0%) | 0.038 |

| Rehospitalisation for HF | 219/859 (25.5) | 204/818 (24.9) | 15/41 (36.6%) | 0.09 |

| Length of stay (days) | 8.1±7.6 | 8.1±7.8 | 7.7±4.3 | 0.86 |

| 12-Month follow-up | ||||

| Death | 139/880 (15.8) | 128/835 (15.3) | 11/45 (24.4%) | 0.10 |

| Rehospitalisation for HF | 333/741 (44.9) | 316/707 (44.7) | 17/34 (50.0%) | 0.54 |

| Length of stay (days) | 9.6±12.0 | 9.6±12.1 | 10.9±11.1 | 0.73 |

The frequencies and percentages for death, rehospitalisation for HF and length of hospital stay. Death rates were cumulative. All values are given as n (%) or mean±SD.

HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Multivariate analysis showed that age, gender, non-compliance to medication, SBP, DBP, creatinine and statins were not predictors of in-hospital mortality in case of non-withdrawal of beta blockers. As expected, inotropic use was significantly associated with higher mortality in our model (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis for intrahospital and 3-month mortality in patients with ADCHF, a LVEF <40% and beta blockers on admission

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Inhospital mortality | |||

| Age | 1.022 | 0.991 to1.055 | 0.17 |

| Gender | 1.058 | 0.428 to2.618 | 0.90 |

| Non-compliance to medication | 1.736 | 0.642 to4.698 | 0.27 |

| SBP | 0.990 | 0.968 to1.014 | 0.41 |

| DBP | 1.003 | 0.964 to1.044 | 0.87 |

| LVEF | 1.053 | 0.998 to1.003 | 0.07 |

| Creatinine | 1.001 | 0.998 to1.001 | 0.59 |

| Aspirin | 1.357 | 0.477 to3.865 | 0.56 |

| Statins | 2.083 | 0.763 to5.684 | 0.15 |

| Inotropes | 20.368 | 8.241 to50.337 | <0.001 |

| Beta blockers on discharge | |||

| Beta blockers withdrawn (reference group) | 1 | – | |

| Beta blockers maintained | 0.050 | 0.022 to0.112 | <0.001 |

| 3-Month mortality | |||

| Age | 1.029 | 1.010 to1.048 | 0.002 |

| Gender | 0.974 | 0.579 to1.638 | 0.92 |

| Non-compliance to medication | 1.267 | 0.753 to2.133 | 0.37 |

| SBP | 0.993 | 0.980 to1.005 | 0.26 |

| DBP | 1.005 | 0.984 to1.026 | 0.66 |

| LVEF | 1.003 | 0.970 to1.037 | 0.87 |

| Creatinine | 1.001 | 1.000 to1.003 | 0.15 |

| Aspirin | 1.516 | 0.828 to2.777 | 0.17 |

| Statins | 1.307 | 0.747 to2.284 | 0.34 |

| Inotropes | 1.456 | 0.759 to2.793 | 0.25 |

| Beta blockers on discharge | |||

| Beta blockers withdrawn (reference group) | 1 | – | |

| Beta blockers maintained | 0.513 | 0.231 to1.143 | 0.10 |

ADCHF, acute decompensated chronic heart failure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Nevertheless, non-withdrawal of beta blockers was associated with less mortality risk even after correcting for all the parameters (OR=0.05, 95% CI 0.022 to 0.112, p<0.001). To confirm our findings, we performed a propensity score matching on inotropic use (see online supplementary table 3). Non-withdrawal of beta blockers was associated with less mortality in the propensity model (OR=0.05, 95% CI 0.015 to 0.170, p<0.001), even after correcting for variables that remained significantly different in the new model (OR=0.084, 95% CI 0.015 to 0.468, p=0.005). At 3 months, fewer deaths also occurred in the group of patients whose beta blockers therapy was not withdrawn (p=0.038). However, after multivariate logistic regression analysis, the protection conferred by beta blockade continuation was lost (OR=0.513, 95% CI 0.231 to 1.143, p=0.10).

In the ADNHF group, 5 (2.2%) in-hospital deaths occurred in patients whose beta blocker therapy was not withdrawn as compared with 17 (47.2%) when beta blockers were discontinued (p<0.001). However, mortality rates were comparable at 3 months and 1 year (table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of non-withdrawal of beta blockers in acute decompensated de novo heart failure with beta blocker therapy on admission and an LVEF <40%

| All patients with de novo heart failure, LVEF<40% and on beta blockers treatment on admission n=260 |

Beta blockers maintained during hospitalisation n=224 (86.2%) |

Beta blockers withdrawn during hospitalisation n=36 (13.8%) |

p Value | |

| Inhospital outcome | ||||

| Death | 22/260 (8.5) | 5/224 (2.2) | 17/36 (47.2) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) | 9.7±16.1 | 9.6±16.6 | 10.1±12.1 | 0.86 |

| 3-Month follow-up | ||||

| Death | 9/232 (3.9) | 7/214 (3.3) | 2/18 (11.1) | 0.14 |

| Rehospitalisation for HF | 39/223 (17.5) | 38/207 (18.4) | 1/16 (6.3) | 0.31 |

| Length of stay (days) | 8.8±9.8 | 8.8±9.9 | 8.0±NE | NE |

| 1-year follow-up | ||||

| Death | 15/221 (6.8) | 13/206 (6.3) | 2/15 (13.3) | 0.27 |

| Rehospitalisation for HF | 61/206 (29.6) | 73/193 (37.8) | 3/13 (23.1) | 0.38 |

| Length of stay (days) | 7.9±7.5 | 8.2±7.6 | 2.7±2.1 | 0.21 |

The frequencies and percentages for death, rehospitalisation for HF and length of hospital stay. Death rates were cumulative. All values are given as n (%) or mean ±SD.

HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NE, not estimable.

Multivariate analysis did not show that age, gender or ACE inhibitors, which were different among both groups, predicted mortality (table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis for intrahospital death in patients with ADNHF, an LVEF <40% and beta blockers on admission

| Variable | OR | 95 % CI | p Value |

| Age | 1.047 | 0.992 to 1.105 | 0.097 |

| Gender | 2.179 | 0.431 to 10.989 | 0.346 |

| ACE-inhibitors | 1.112 | 0.215 to 5.757 | 0.899 |

| Inotropes | 172.272 | 16.002 to 1854.600 | <0.001 |

| Beta blockers | |||

| Beta blockers withdrawn (reference group) | 1 | ||

| Beta blockers maintained | 0.018 | 0.003 to 0.122 | <0.001* |

ADNHF, acute de novo heart failure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Similarly, to the ADCHF, inotropic use was highly associated with mortality. We also performed a propensity score matching on inotropic use (see online supplementary table 4) and confirmed that beta blocker continuation in ADNHF has a favourable outcome (OR=0.05, 95% CI 0.015 to 0.170, p<0.001), even after correcting for variables that remained significantly different between both groups in the new model (OR=0.047, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.169, p<0.001). Similarly to patients with ADCHF, re-hospitalisation for HF and length of hospital stay were unaffected by the withdrawal of beta blockers.

Discussion

This observational study demonstrates that pursuing beta blocker therapy during acute HF confers to patients with chronic and de novo acute HF cardiovascular protection and decreases mortality. Interestingly, randomised placebo-controlled trials that assessed pursuing beta blockers versus withdrawal during acute HF are missing; available data are extrapolated from post hoc analysis. The B-convinced was designed as a non-inferiority trial and demonstrated only safety of beta blockers during acute decompensation.9 In a retrospective analysis of the SURVIVE study that initially assessed two inotropic treatments in critical patients with acute HF, the benefit associated with non-withdrawal of beta blockers was lost after correcting for HF covariates; only patients who never received beta blockers had a worse outcome as compared with patients who were on these drugs at inclusion and on discharge.10 In a subanalysis of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization (ESCAPE) that assessed pulmonary artery catheter use among patients admitted with acute HF, patients already prescribed beta blockers on admission had a lower 6-month mortality risk and a shorter hospitalisation stay.13 Outcomes of the Prospective Trial of Intravenous Milrinone for Exacerbations of Chronic Heart Failure (OPTIME-CHF), designed as a randomised placebo-controlled trial, failed to test the superiority of milnirone to placebo in patients with ADCHF.14 Further observational analysis showed that withdrawal of beta blockers was associated with a greater risk of 2-month mortality and rehospitalisation for HF despite limitations due to the use of milnirone in those patients and the small number of patients analysed.15

Our results are comparable to previous observational studies from North America and Europe. In the Italian Survey on Acute Heart Failure, withdrawal of beta blockers during acute HF was associated with almost fourfold increase in the risk of intrahospital mortality.16 The Organised Programme to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalised Patients with Heart Failure is one of the largest Northern American registries of patients admitted with acute HF. Maintenance of beta blockers during acute decompensation was associated with better outcome in postdischarge mortality.17 Consistent with our findings, Prins et al reported in a recent meta-analysis that included over 2700 patients treated with beta blockers and hospitalised for acute HF, that withdrawal of beta blockers significantly increased in-hospital and short-term mortality, and rehospitalisation for HF.18

Despite firm safety data and undoubted long-term benefit, beta blocker therapy remains underprescribed. In our study, only 44.1% of all patients presenting with acute HF and 44.2% of patients with a LVEF <40% were treated with beta blockers. The frequency of beta blockers prescription is variable according to cohorts and ranges from 32% in the ‘Italian Survey on Acute Heart Failure’ study16 to 53.3% in the SURVIVE study10 and 62% in the ESCAPE trial.13

It is not known why withdrawal of beta blockers in acute HF is associated with a worse prognosis. Activation of the sympathetic system, increase of catecholamine levels and alterations in cardiac beta (β)-receptors are the hallmark of chronic HF; therefore beta blocker therapy in chronic HF could limit the deleterious effect of chronic β-receptor stimulation such as arrhythmias, hypertrophy and cardiomyocytes apoptosis.19 It may be possible that withdrawal of beta blockers in the acute phase takes away earlier protective effect of β-adrenergic inhibition at a time when the neurohormonal system is activated and catecholamines are significantly increased.20

Managing beta blockers during acute HF is still unclear to most physicians. The Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure trial investigators were the first to report that in-hospital initiation of beta blockers was safe compared with postdischarge.21 The latest guidelines from both the Society of Cardiology22 and the American College of Cardiology foundation/American heart association23 recommend initiating a beta blocker therapy following acute HF as soon as the patient is stable and before discharge. However, uncertainty persists in regards to continuing beta blockers during an acute decompensation. Beta blockade therapy discontinuation during AHF is variable. In older studies such as the OPTIME-CHF, beta blockers were withdrawn in over 20% of patients.15 In our study, beta blockers were withdrawn in 9% of patients with ADCHF and 13.8% of patients with ADNHF. Those numbers are almost similar to the Italian Survey on Acute Heart Failure in which Orso et al reported a withdrawal rate of 9% in all patients with AHF with beta blockers on admission16 However, Bohm et al reported a lower rate (6.8%) in the retrospective analysis of the SURVIVE study.10

It is not known why mortality risk reduction extends up to 3 months in ADCHF but not in ADNHF although the first group has higher cardiovascular comorbidities and more severe risk factors. One explanation could be the higher prescription of cardioprotective drugs such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs and diuretics; all having shown to reduce mortality in patients with chronic HF and improve the outcome.24–26 One other explanation would also be the frequent use of beta blockers approved for HF in patients with ADCHF, whereas the prescription of non-HF selective beta blockers such as atenolol was more common in ADNHF. Finally, we cannot rule out that the relatively small number of patients with ADNHF, coupled to an even smaller death rate at 3 months, does not enable us draw any meaningful conclusions on long-term mortality in those patients.

Our study has a few limitations. Like any observational study, selection bias could exist. The decision of beta blocker withdrawal during acute HF could have been to different factors not accounted for in our analysis such as their side effects. Above all, beta blocker therapy could have been withdrawn in the more severe patients with a poor prognosis. Despite the correction on available cofounding factors, we could have missed other markers of disease severity that were not recorded in the cohort. In addition, we could not determine whether the dosage of beta blockers on admission, or any reduction during hospitalisation, might have influenced the outcome. Finally, the duration of beta blocker treatment prior to acute HF was not recorded; this variable could also be a confounding factor since long-term beta blocker treatment could have been more beneficial than short term.

Conclusion

Our study suggests non-withdrawal of beta blocker therapy during acute heart failure reduces intrahospital mortality risk in patients with acute decompensated chronic and de novo heart failure, but does not influence 3- and 12- month mortalities, rehospitalisation for heart failure and the length of hospital stay. Our findings could only be validated in randomised controlled trials designed to show the superiority of non-withdrawal of beta blockade therapy and also determine whether beta blocker dose should be reduced or kept unchanged compared with a withdrawal strategy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Andrew Bliszczyk for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS, KFA, NA, AA-A, MA-J, BB, WA, MR, NB, HA, AA-M, HAF, AE, PP and JAS were involved in the design of the Gulf CARE registry and patient enrolment and ensuring quality control of the study. CAK designed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. ZM and RS carried out the statistical analyses. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Gulf CARE is an investigator-initiated study conducted under the auspices of the Gulf Heart Association and funded by Servier, Paris, France and (for centres in Saudi Arabia) by the Saudi HeartAssociation. Dr Abi Khalil’s lab is funded by the Biomedical Research Program (BMRP) at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, a programme funded by Qatar Foundation, and by two grants from the Qatar National Research Funds under its National Priorities Research Program award numbers (NPRP 7 - 701 - 3 – 192 and NPRP 9-169-3-024). Dr Al-Habib’s lab is funded by the Saudi Heart Association and The Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (research group number: RG -14360-013).

Disclaimer: The funders did not have a role in the study’s concept, analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The registry protocol was approved by each participating centre’s institutional review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data include human data. To protect participant privacy, the data are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999;353:2001–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krum H, Roecker EB, Mohacsi P, et al. Effects of initiating carvedilol in patients with severe chronic heart failure: results from the COPERNICUS Study. JAMA 2003;289:712–8. 10.1001/jama.289.6.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1349–55. 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013;128:1810–52. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foody JM, Farrell MH, Krumholz HM. beta-Blocker therapy in heart failure: scientific review. JAMA 2002;287:883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nieminen MS, Brutsaert D, Dickstein K, et al. EuroHeart Failure Survey II (EHFS II): a survey on hospitalized acute heart failure patients: description of population. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2725–36. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harjola VP, Follath F, Nieminen MS, et al. Characteristics, outcomes, and predictors of mortality at 3 months and 1 year in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:239–48. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jondeau G, Neuder Y, Eicher JC, et al. B-CONVINCED: Beta-blocker CONtinuation Vs. INterruption in patients with Congestive heart failure hospitalizED for a decompensation episode. Eur Heart J 2009;30:2186–92. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Böhm M, Link A, Cai D, et al. Beneficial association of β-blocker therapy on recovery from severe acute heart failure treatment: data from the Survival of Patients With Acute Heart Failure in Need of Intravenous Inotropic Support trial. Crit Care Med 2011;39:940–4. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a91ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sulaiman K, Panduranga P, Al-Zakwani I, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of acute heart failure patients: observations from the Gulf acute heart failure registry (Gulf CARE). Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:374–84. 10.1002/ejhf.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sulaiman KJ, Panduranga P, Al-Zakwani I, et al. Rationale, Design, Methodology and Hospital Characteristics of the First Gulf Acute Heart Failure Registry (Gulf CARE). Heart Views 2014;15:6–12. 10.4103/1995-705X.132137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butler J, Young JB, Abraham WT, et al. Beta-blocker use and outcomes among hospitalized heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2462–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cuffe MS, Califf RM, Adams KF, et al. Short-term intravenous milrinone for acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:1541–7. 10.1001/jama.287.12.1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gattis WA, O'Connor CM, Leimberger JD, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients on beta-blocker therapy admitted with worsening chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:169–74. 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)03104-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Orso F, Baldasseroni S, Fabbri G, et al. Role of beta-blockers in patients admitted for worsening heart failure in a real world setting: data from the Italian Survey on Acute Heart Failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:77–84. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Influence of beta-blocker continuation or withdrawal on outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:190–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prins KW, Neill JM, Tyler JO, et al. Effects of Beta-Blocker Withdrawal in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:647–53. 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S, Eschenhagen T. What is the role of beta-adrenergic signaling in heart failure? Circ Res 2003;93:896–906. 10.1161/01.RES.0000102042.83024.CA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Onwuanyi A, Taylor M. Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: Pathophysiology and Treatment. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:S25–S30. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gattis WA, O'Connor CM, Gallup DS, et al. Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT-HF) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1534–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:803–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 20132013;128:e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet 2003;362:772–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, et al. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991;325:293–302. 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al. Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2049–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa042934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014915supp001.pdf (95.2KB, pdf)