Abstract

Objectives

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in youth, with a prevalence of about 3%–4% and increased risk of adverse long-term outcomes, such as depression. Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is considered the first-line treatment for youth with SAD, but many adolescents remain untreated due to limited accessibility to CBT. The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a therapist-guided internet-delivered CBT treatment, supplemented with clinic-based group exposure sessions (BIP SOFT).

Design

A proof-of-concept, open clinical trial with 6-month follow-up.

Participants

The trial was conducted at a child and adolescent psychiatric research clinic, and participants (n=30) were 13–17 years old (83% girls) with a principal diagnosis of SAD.

Intervention

12 weeks of intervention, consisting of nine remote therapist-guided internet-delivered CBT sessions and three group exposure sessions at the clinic for the adolescents and five internet-delivered sessions for the parents.

Results

Adolescents were generally satisfied with the treatment, and the completion rate of internet modules, as well as attendance at group sessions, was high. Post-treatment assessment showed a significant decrease in clinician-rated, adolescent-rated and parent-rated social anxiety (d=1.17, 0.85 and 0.79, respectively), as well as in general self-rated and parent-rated anxiety and depression (d=0.76 and 0.51), compared with pretreatment levels. Furthermore, 47% of participants no longer met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for SAD at post-treatment. At a 6-month follow-up, symptom reductions were maintained, or further improved, and 57% of participants no longer met criteria for SAD.

Conclusion

Therapist-guided and parent-guided internet-delivered CBT, supplemented with a limited number of group exposure sessions, is a feasible and promising intervention for adolescents with SAD.

Trial registration number

NCT02576171; Results.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of a combined internet cognitive–behavioural therapy and group exposure treatment for youth with social anxiety disorder.

Participants were followed up 6 months after the end of treatment.

The study was uncontrolled that limits any causal inference about observed changes.

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterised by an intense fear of being scrutinised and negatively evaluated in social or performance situations.1 The socially anxious individual is typically afraid of making mistakes, being embarrassed in front of others and of showing signs of anxiety, such as blushing or trembling, and may therefore avoid social and performance situations or endure them under intense distress. The disorder has a median age of onset of 9.2 years2 and is one of the most common mental disorders among adolescents. SAD is more common in adolescent girls than in adolescent boys with a female to male OR of 1.58 (95% CI 1.18 to 2.12).2 The 12-month prevalence is 3.4%3 and 8.6% of the adolescent population fulfil diagnostic criteria at some point between the age of 13 and 18 years.2 If the disorder is left untreated, it tends to follow a chronic course2 and can lead to severe secondary consequences such as depression4 and suicidality,5 substance and alcohol dependence,6 academic underperformance and increased social isolation.7 Consequently, SAD causes substantial impairment as well as burden on patients’ families and long-term societal costs.8 9

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for SAD is effective for adults10 as well as for children and adolescents11 12 and is the first-line treatment according to international clinical guidelines (eg, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).13 In face-to-face treatment, generic CBT has shown poorer outcomes for youth with SAD compared with other anxiety disorders,14 but when treatments have been tailored to include SAD-specific components, such as social skills training, the reported effects have been larger.15 16

Despite the high level of impairment caused by the disorder, only a small proportion of adolescents with social anxiety seek help for their problems17 18 and even fewer receive effective treatment.19 Barriers to receiving evidence-based psychological treatment include limited availability of trained therapists, and practical issues such as long travel distances to clinics, and the requirement to take time off school or work to visit a clinic.

Internet-delivered CBT (ICBT) has been suggested as a possible solution to some of these barriers. It can provide the same treatment components as traditional CBT and allow patients to work from home (or wherever suitable), guided by an online therapist, for example, through email or similar online communication. Treatment becomes more accessible as the therapist and patient can communicate asynchronously, and it may increase treatment capacity, as therapist time per patient tends to be lower compared with face-to-face CBT.20–22 For adults with SAD, ICBT is an evidence-based treatment23 with at least one trial showing that ICBT is non-inferior to face-to-face CBT.24 For youth, ICBT is effective for mixed anxiety disorders when compared with a waitlist control,25–28 with similar effects as face-to-face CBT,29 suggesting that ICBT could be a suitable treatment for adolescents with SAD. However, a recent study showed that only 12.8% and 14.6% (in the SAD specific and generic ICBT conditions, respectively) of participants were free from their SAD diagnosis at post-treatment assessment, indicating that using the internet as the only modality to deliver CBT might not be sufficient.30 Earlier findings suggest that face-to-face CBT supported by computerised CBT may be more effective than standalone ICBT for adolescents and young adults with anxiety disorders.31 32 Furthermore, it has been suggested that ICBT combined with face-to-face CBT may be beneficial for adult patients with SAD33 and depression.34 Such a treatment has, however, never been developed for adolescents with SAD before, and the objective of the current trial is to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of ICBT supplemented with clinic-based group exposure sessions for adolescents with SAD. This treatment could potentially draw on advantages from both formats, where ICBT is a cost-effective and accessible format and group sessions may ensure that key treatment components, such as exposure to social situations and social skills training, are conveyed properly. Main research questions are: is the treatment (BIP SOFT) feasible and acceptable with regard to adolescents’ and parents’ willingness to work with the internet modules, adolescents’ attendance rates at group sessions and treatment satisfaction? Does the treatment reduce social anxiety symptoms and increase adolescents’ level of functioning and quality of life?

Method

The study was conducted at a research unit within the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in Stockholm, Sweden. Participants were recruited and treated between October 2015 and May 2016.

Participants

Participants were 30 adolescents, 13–17 years old, with a principal diagnosis of SAD, and their parents. Table 1 gives detailed information on demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Inclusion criteria were: (A) age 13–17 years, (B) principal DSM-5 diagnosis of SAD, (C) ability to read and write Swedish, (D) access to a computer with internet access and (e) at least one parent being able to participate in the treatment. Exclusion criteria were: (F) initiation or dose modification of psychotropic drug within the past 6 weeks, (G) ≥5 sessions of CBT (including exposure) within the last 6 months, (H) any ongoing psychological treatment for SAD, (I) diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, current psychosis, eating disorder, severe depression, suicidal behaviour or other current severe psychiatric condition and (J) current substance or alcohol abuse. Most participants who were excluded at the initial screening fulfilled an exclusion criterion, due to having either initiated selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medication (or modified the dose) recently, for having received CBT within the last 6 months or for being diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Adolescents excluded due to other severe psychiatric conditions, such as severe depression or suicidality, were referred to more suitable treatments.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of study participants (n=30)

| Variables | N | % |

| Age (years) | ||

| M (SD) | 15 (1.22) | |

| Min–max | 13–17 | |

| Gender | ||

| Girls | 25 | 83 |

| Boys | 5 | 17 |

| Country of birth, adolescent | ||

| Sweden | 29 | 97 |

| Other | 1 | 3 |

| Country of birth, parents | ||

| Both in Sweden | 20 | 67 |

| One in Sweden | 7 | 23 |

| None in Sweden | 3 | 10 |

| Education, responding parent | ||

| Primary | 14 | 47 |

| Higher | 16 | 53 |

| Employment, responding parent | ||

| Working | 25 | 83 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 13 |

| Retired | 1 | 3 |

| Psychotropic medication pretreatment | ||

| None | 27 | 90 |

| SSRI | 3 | 10 |

| Prior psychological treatment | ||

| None | 11 | 37 |

| Primary care, counselling or equivalent | 4 | 13 |

| Psychiatric specialist care or equivalent | 14 | 47 |

| Referred from child health services | 6 | 20 |

| Comorbid diagnoses | ||

| Specific phobia | 8 | 26.7 |

| GAD | 5 | 16.7 |

| ADD | 3 | 10 |

| Depression | 2 | 6.7 |

| OCD | 2 | 6.7 |

| Panic disorder | 1 | 3.3 |

| Tics/Tourette | 1 | 3.3 |

| Separation anxiety | 1 | 3.3 |

| Trichotillomania | 1 | 3.3 |

| Frequency of comorbid diagnoses | ||

| None | 13 | 43.3 |

| One | 11 | 36.7 |

| Two | 3 | 10 |

| Three or more | 3 | 10 |

| Onset (age in years) | ||

| M (SD) | 8.9 (4.29) | |

| Duration of SAD (years) | ||

| M (SD) | 6.2 (4.05) | |

Note: primary education ≤12. Higher education >12 years.

ADD, attention deficit disorder; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors .

Participants were mainly recruited through advertisement in a local paper. The advertisement included a website address (www.bup.se/bip) where interested families could get study information and sign up. Clinicians working in the child and adolescent health services could also refer patients to the trial.

To achieve sufficient power and to be able to detect a within-group effect size of d=0.60 from pre to post with a power of 0.85 and α=0.05, allowing for a 10% drop out, we included 30 participants in the study.

Measures

Primary outcome measures

The Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI-S)35 is a clinician rating of symptom severity, ranging from 1 (‘normal, not mentally ill’) to 7 (‘extremely ill’). The CGI-S was administered at baseline by the treating therapist. At post-treatment and the 6-month follow-up, another clinician than the one being responsible for the treatment administered the CGI-S.

Secondary outcome measures

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI KID)36 was used to determine presence of SAD, as well as comorbid conditions. In addition, the SAD section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child Version (ADIS-C)37 was used to further confirm SAD diagnosis and to assess the intensity of SAD symptoms. An independent rater (a clinical psychologist, not part of the research group, blind to whether the adolescent had been included in the study or not) watched recordings of the baseline interviews and reassessed 20% of them (both included and excluded adolescents), generating an excellent inter-rater reliability at pretreatment for SAD diagnosis (κ=1.0) and a fair inter-rater reliability for comorbidity (κ=0.46, p<0.05).

Clinical Global Impression – Improvement (CGI-I)35 is a clinician rating of the participant’s change in symptom severity relative to baseline, ranging from 1 (‘very much improved’) to 7 (‘very much worse’). The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)38 is a clinician rating of global functioning (scale 0–100), with higher rating indicating higher level of functioning. The MINI KID and CGAS were administered at baseline, post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up, whereas the CGI-I was administered post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up.

Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory – Child and Parent Version (SPAI-C/P)39 is a 26-item self-report measure evaluating aspects of SAD on a three-point scale, where a score of ≥18 is considered the clinical level of social anxiety. The Social Phobia Weekly Summary Scale (SPWSS) is a five-item self-report scale40 41 measuring dimensions of SAD (social anxiety, avoidance, self-focused attention, anticipatory processing and postevent processing). The SPAI-C/P and the SPWSS were administered at baseline, every third week during treatment, post-treatment as well as at the 6-month follow-up.

The Revised Children Anxiety And Depression Scale – Child and Parent Version (RCADS-C/P)42 is a 47-item self-report measure evaluating anxiety disorders (including one subscale for SAD) and depression on a four-point scale, ranging from never to always. In the current trial, one item regarding suicidality, with three options (‘I do not think about killing myself’, ‘I think about killing myself, but would never do it’ or ‘I want to kill myself’) was added at the end of the RCADS-C/P. The Education, Work and Social Adjustment Scale – Child and Parent Version (EWSAS-C/P)43 44 is a five-item self-report scale measuring functional impairment on a nine-point scale (higher rating indicating more impairment). The RCADS-C/P and the EWSAS-C/P were administered at baseline, after 6 weeks of treatment, post-treatment as well as at the 6-month follow-up.

The health-related quality of life questionnaire for children, adolescents and their parents (KIDSCREEN-10)45 is a self-report measure assessing health-related quality of life. The parent-rated measure Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness – Child version (TiC-P)46 covers, for example, production loss among parents due to health problems in the child. The KIDSCREEN-10 and the TiC-P were administered at baseline, post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up.

Feasibility measures, adverse events and therapist time

The Technology Acceptance Scale – child and parent version (TAS-C/P) is a self-report measure adapted from Venkatesh et al,47 which measures the usefulness, acceptability and satisfaction of the website through which the internet modules of the treatment were delivered. The TAS-C/P was administered after 3 weeks of treatment and post-treatment.

At post-treatment, adolescents and parents were asked to report any negative experiences or adverse events over the course of treatment as well as to what extent the negative event had affected the adolescent’s well-being.

Amount of therapist time per participant was logged automatically through the internet treatment platform.

Procedure

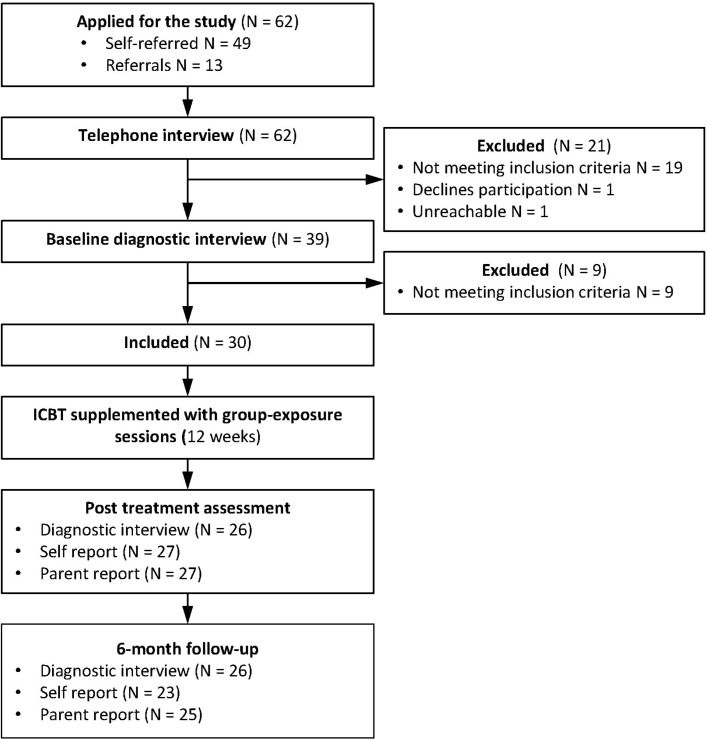

Figure 1 gives an overview of inclusion procedures and assessment points. Families who applied to the study were contacted by telephone, and a short screening interview was conducted. Eligible families were invited to diagnostic assessment at the clinic. After thorough information about the study, adolescents gave verbal assent to participate, and written informed consent was obtained from parents. The screening interview MINI KID (with the supplement of the SAD section of the ADIS-C) was then conducted. The therapist who conducted the baseline assessment was responsible for the treatment of the participant.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. ICBT, internet-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy.

Adolescents with a principal diagnosis of SAD were included, and adolescents and parents completed baseline self-report measures online through the treatment platform. In each family, one of the parents was assigned the main responsibility to respond to the parent-report measures at each assessment point throughout the study. Adolescents and parents had separate user accounts and a two-factor authentication (an individual password and a single-use code sent to the user’s cellular phone) gave access to the online platform.

Self-rated and parent-rated measures administered during the treatment (SPAI-C/P, SPWSS, RCADS C/P and EWSAS C/P) were completed online.

At post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up, all participating adolescents and parents were invited back to the clinic for a diagnostic assessment. To reduce the risk of biased assessment, a clinician that had not been responsible for the participant’s treatment conducted the post-treatment and follow-up assessments. All self-assessment scales were administered online post-treatment and at follow-up. Families who could not come to the clinic for post-treatment assessment (n=1) and 6-month follow-up (n=3) were assessed over the telephone.

Intervention

The intervention was 12 weeks of ICBT supplemented with group exposure, comprising nine internet-delivered modules completed individually from home and three group exposure sessions at the clinic (table 2). The online treatment platform used in this study was developed for delivery of ICBT and has been tested in a number of previous studies for different psychiatric disorders in youth.22 28 48–50 The current treatment (BIP SOFT) was based on the cognitive–behavioural model by Rapee and Heimberg51 and to some extent on the cognitive model by Clark and Wells.52 The treatment manual was developed by the authors and contains CBT components commonly used for SAD in youth,15 53 54 such as exposure, coping strategies and social skills training. The group sessions were mostly based on the Albano and DiBartolo54 group CBT manual for adolescent SAD. Therapists in the study were three clinical psychologists and two master students at their final year of training in clinical psychology.

Table 2.

An overview of the content of the ICBT protocol and group exposure sessions

| Chapter | Adolescent | Parent | Group exposure sessions |

| 1 | Introduction to ICBT. Learn about emotions, fear and social anxiety. How to do functional analyses of my own behaviour. | Introduction to ICBT. Learn about emotions, fear and social anxiety. How to do functional analyses of my teenager’s behaviour and my own reactions. | |

| 2 | More about social anxiety disorder. Learn to reduce self-focus and safety behaviours. Improve coping strategies. | Suggest treatment goals. Plan the treatment. Learn about exposure and how to be a cotherapist during exposure. | |

| 3 | Map the social anxiety. Learn about exposure to social situations. Set treatment goals and build an individual exposure hierarchy. | Learn about common parental challenges. How to reward my adolescent. Problem solving. | |

| 4 | How to handle negative thoughts. Learn about social skills. | Modelling and practice of social skills. Modelling and mapping of safety behaviours and how to reduce them. Set an individual exposure hierarchy. Exposure in vivo. Summary with parents. | |

| 5 | Exposure follow-up. Learn about negative thoughts and how to handle them. | Prepare relapse prevention. Evaluation of parent modules and treatment. | |

| 6 | Repetition of treatment components. Exposure in vivo. Summary with parents. | ||

| 7 | Exposure follow-up. Extended practice of focus shift. | ||

| 8 | Exposure follow-up. Negative thoughts follow-up. Problem solving. | ||

| 9 | Exposure follow-up. Learn how to say no and other self-assertive behaviours. | ||

| 10 | Exposure in vivo. Social mishaps in public environment. Summary with parents. | ||

| 11 | Exposure follow-up. Last sprint: how to get the most out of the last exposures. | ||

| 12 | Make a plan for relapse prevention. What did I learn? What do I want to practice further? Make an evaluation of the treatment. |

ICBT, internet-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy.

The internet modules included educative texts, animations, audio clips and exercises. The parental part of the intervention consisted of five internet modules with parent-specific topics such as ‘parental traps’ (eg, compensating for the adolescent in social situations by for instance speaking for him/her) and doing functional analyses of such parental accommodation (table 2). Parents were encouraged to be actively involved in their adolescent’s treatment and discuss with the adolescent how they should support him or her throughout the treatment, for example, during exposure exercises. Parents were also encouraged to bring up parent-specific topics with their therapist, for example, how to support the adolescent before or during exposures. Parents could send messages to the therapist throughout the 12 weeks of treatment with the purpose to keep parents active as cotherapists. Therapists were instructed to only give support on actual treatment content and to only answer messages about the adolescents (or about parents’ relationship with the adolescents) and not regarding parents’ own difficulties. Adolescents and parents were instructed to log in and complete one module each week. The modules were assigned in a predetermined order, and therefore, all modules but the first were initially locked. Once the participant completed a module, the therapist made the next one available.

The therapists had asynchronous contact online with adolescents and parents every week, commenting on their progress on work sheets and through a built-in message function. Therapists were instructed to log in and provide feedback to their families three times per week. If necessary, therapists had telephone contact with families, for example, if they had not logged in during the last week or if midtreatment self-reports exceeded a cut-off for depression (>11 on RCADS-C depression subscale) or suicidality.

The group exposure sessions (at weeks 4, 6 and 10) ensured that key components of the treatment were demonstrated in a correct way and that participants could practice, for example, exposure under observation of a therapist. To ensure large enough group sizes, cohorts of six participants started the treatment at the same time. The group sessions were 2 hours long and led by two of the clinical psychologists.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS V.23.

Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ)55 was used to calculate inter-rater reliability for SAD diagnosis and comorbidity at pretreatment assessment. The level of reliability is interpreted as poor when κ <0.40, fair when κ is 0.40–0.59, good when κ is 0.60–0.74 and excellent when κ >0.74.56

Linear mixed models were used to analyse changes from pretreatment to post-treatment and from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up. Mixed model analyses use all available data and account for correlations between measurements within the same subject.57 Thus, missing data are handled within the model. All mixed models in this study included a fixed effect for time (pre, post and 6-month follow-up) and a random effect for individual subjects. Potential missing bias was investigated using t-tests that compared the baseline characteristics of those who had complete data at post-treatment with those who had missing data. For SPAI C/P and SPWSS, three midtreatment (weeks 3, 6 and 9) time points were included in the analyses, and for RCADS C/P and EWSAS C/P, one midtreatment (week 6) time point was included in the analyses.

Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d=(M1−M2/SDpooled). Effect sizes are defined according to Cohen’s suggested levels: small (d≥0.20), moderate (d≥0.50) and large (d≥0.80).58

Results

Response rate and feasibility

Midtreatment measures were completed by 97% of the participating families at week three, 83% at week six and 70% at week nine. Post-treatment and 6-month follow-up measures were completed by 90% and 83% of the participating families, respectively. t-Tests comparing participants with missing versus complete data points on baseline characteristics revealed no statistically significant differences.

Adolescents completed on average 5.7 (SD=2.1) of the nine internet modules and parents completed on average 4.4 (SD=1.0) of their five modules. The frequency of completed modules by the adolescents was distributed as follows: 20% (n=6) completed 2–3 modules, 43% (n=13) completed 4–6 modules and 37% (n=11) completed 7–9 modules. None completed fewer than two modules.

Attendance at the group sessions were 70% (session 1), 77% (session 2) and 63% (session 3), respectively. Two-thirds of the participants attended two or more group sessions and only 10% attended none.

None of the adolescents meeting inclusion criteria at baseline assessment declined participation, which indicates good acceptability of the offered treatment.

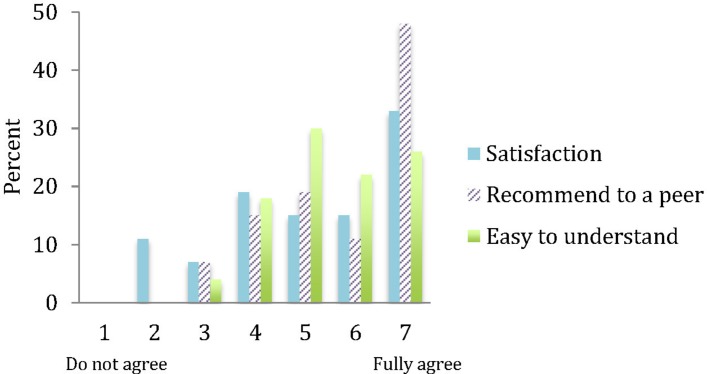

Figure 2 illustrates that a majority of the adolescents were satisfied with the treatment, would recommend the treatment to a friend and found the programme easy to understand. Furthermore, most of the participating adolescents found the treatment’s online platform easy to use, with a mean rating of 5.6 (range 4–7) on the seven-point TAS scale item (were 7 indicates full agreement with the statement ‘The program was easy to use’).

Figure 2.

Adolescents’ evaluation of BIP SOFT.

Clinician support

The average time a clinician spent giving feedback and guidance to participants (including time spent on the adolescent and parent) was 19.5 min per week for the internet modules. Group sessions required 2 hours of therapist time per participant in total during the 12 weeks, which corresponds to 10 min per week and participant. In total thus, each family got 29.5 min of therapist time, per week.

Changes in clinical outcomes from pretreatment to post-treatment

Means, SD and effect sizes for pre to post changes are presented in table 3. Intention-to-treat analyses of the primary outcome measure (CGI-S) showed a significant decrease of SAD severity from pretreatment to post-treatment, t(26.05)=5.62, p<0.001, with a large effect size, d=1.17 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.72). For all secondary outcome measures, analyses revealed significant improvements with moderate to large effect sizes, with the exception of quality of life (KIDSCREEN-C/P) where a small effect was observed. At post-treatment, 47% of the participants (n=14) no longer met diagnostic criteria for SAD, according to DSM-5 criteria and a CGI rating <4 (level of severity and functional impairment below diagnostic threshold) and 30% (n=9) scored ≤18 on SPAI-C (cut-off for clinical level of social anxiety). On the clinician-rated CGI-I, 8% (n=2) were ‘very much improved’, 23% (n=6) ‘much improved’, 42% (n=11) ‘minimally improved’, 23% (n=6) ‘not changed’ and 4% (n=1) ‘minimally worse’.

Table 3.

Means, SD, pre to post and post to 6-month follow-up comparisons and effect sizes of all outcome measures

| Pre | Post | Pre to post comparison | 6-month follow-up | Post to follow-up comparison | ||||||

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | p | d (95% CI) | M | SD | p | d (95% CI) |

| Clinician rated | ||||||||||

| CGI-S | 4.6 | 0.72 | 3.3 | 1.3 | <0.001 | 1.17 (0.61 to 1.72) | 3.0 | 1.43 | 0.015 | 0.22 (−0.01 to 0.45) |

| C-GAS | 55.5 | 6.68 | 62.0 | 8.85 | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.40 to 1.21) | 65.4 | 11.14 | <0.001 | 0.30 (0.13 to 0.46) |

| Self-rated and parent-rated social anxiety | ||||||||||

| SPAI-C | 33.4 | 9.32 | 24.5 | 11.31 | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.36 to 1.34) | 21.5 | 11.24 | 0.023 | 0.27 (0.02 to 0.51) |

| SPAI-P | 35.3 | 8.46 | 27.2 | 11.55 | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.29 to 1.28) | 25.7 | 11.01 | n.s. | |

| SPWSS avoid | 4.0 | 2.38 | 1.9 | 2.22 | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.36 to 1.47) | 1.8 | 1.81 | <0.001 | 0.05 (−0.4 to 0.5) |

| SPWSS s-f | 4.9 | 1.74 | 2.8 | 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.31 (0.61 to 2.02) | 3.3 | 2.03 | <0.001 | −0.28 (−0.83 to 0.26) |

| SPWSS a a | 4.9 | 1.85 | 3.0 | 2.19 | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.32 to 1.55) | 2.4 | 1.92 | <0.001 | 0.29 (−0.18 to 0.76) |

| SPWSS pep | 4.8 | 2.29 | 3.6 | 1.77 | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.02 to 1.15) | 3.3 | 2.30 | <0.001 | 0.14 (−0.36 to 0.65) |

| Other self-rated and parent-rated measures | ||||||||||

| RCADS-C SAD | 18.5 | 5.69 | 14.2 | 5.87 | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.36 to 1.13) | 12.4 | 6.16 | 0.018 | 0.30 (0.05 to 0.55) |

| RCADS-P SAD | 16.4 | 5.88 | 13.2 | 5.70 | 0.006 | 0.55 (0.09 to 1.01) | 12.3 | 6.07 | n.s. | |

| RCADS-C | 60.0 | 24.77 | 42.1 | 21.74 | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.32 to 1.21) | 38.4 | 25.92 | n.s. | |

| RCADS-P | 46.2 | 23.39 | 35.2 | 19.13 | 0.005 | 0.51 (0.11 to 0.91) | 31.8 | 22.31 | n.s. | |

| KIDSCREEN-C | 32.2 | 5.59 | 34.1 | 6.07 | 0.036 | 0.32 (0.06 to 0.59) | 35.7 | 6.93 | n.s. | |

| KIDSCREEN-P | 33.1 | 4.50 | 35.5 | 5.98 | 0.025 | 0.44 (0.06 to 0.82) | 35.8 | 5.85 | n.s. | |

| EWSAS-C | 15.0 | 7.47 | 10.9 | 6.69 | 0.006 | 0.58 (0.14 to 1.01) | 7.8 | 5.28 | 0.004 | 0.50 (0.1 to 0.91) |

| EWSAS-P | 14.6 | 6.51 | 11.4 | 6.88 | 0.002 | 0.48 (0.13 to 0.83) | 9.1 | 7.44 | 0.002 | 0.31 (0.1 to 0.54) |

C-GAS, Children’s Global Assessment Scale; CGI-S, The Clinical Global Impression – Severity; EWSAS-C/P, The Education, Work and Social Adjustment Scale – Child and Parent Version; KIDSCREEN-C/P, The health-related quality of life questionnaire for children, adolescents and their parents; RCADS-C/P, The Revised Children Anxiety And Depression Scale – Child and Parent Version; RCADS-C/P SAD, The Revised Children Anxiety And Depression Scale – Child and Parent Version, SAD subscale; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SPAI-C/P, Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory – Child and Parent Version; SPWSS, The Social Phobia Weekly Summary Scale; SPWSS a a, SPWSS anticipatory anxiety; SPWSS avoid, SPWSS avoidance; SPWSS s-f, SPWSS self-focus; SPWSS pep, postevent processing.

Changes in clinical outcomes from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up

Table 3 gives an overview of means, SD and effect sizes from post-treatment to the 6-month follow-up. The improvements seen at post-treatment were generally maintained and further augmented at the 6-month follow-up with small effect sizes, except for self-focus (SPWSS) that deteriorated slightly. The primary outcome measure (CGI-S) showed a significant decrease of SAD severity from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up, t(25.45)=2.60, p<0.05, with a small effect size, d=0.22 (95% CI −0.01 to 0.45). At follow-up, 57% (n=17) no longer met diagnostic criteria for SAD and 37% (n=11) scored ≤18 on SPAI-C.

Comparison of pretreatment and 6-month follow-up levels of social anxiety showed overall improvements with large effect sizes: CGI-S: t(27.23)=6.24, p<0.001, d=1.36 (95% CI 0.71 to 2.01), SPAI-C: t(27.63)=5.50, p<0.001, d=0.95 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.39) and SPAI-P: t(26.08)=5.57, p<0.001, d=1.14 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.72). Clinician-rated CGI-I indicated that, of those who participated in the 6-month follow-up assessment, 19% (n=5) were ‘very much improved’, 31% (n=8) ‘much improved’, 38% (n=10) ‘minimally improved’, 4% (n=1) ‘not changed’ and 8% (n=2) ‘minimally worse’, compared with baseline.

Post hoc analyses

The proportion of parents reporting that they had stayed home from work during the last month due to their adolescent’s health problems was 27% before treatment and 13% at 6-month follow-up. Of the adolescents, 50% had stayed home from school during the last month due to health problems before treatment and 33% at 6-monthfollow-up.

At 6-month follow-up, six participants reported that they had received additional treatment for social anxiety; two participants (7%) got CBT and four participants (13%) had initiated or increased SSRI medication. All these participants fulfilled diagnostic criteria for SAD at post-treatment assessment and five out of six still fulfilled diagnostic criteria for SAD at follow-up.

Half of all participants (n=15) reported that they had used strategies from the treatment since post-treatment assessment, referring to exposure, coping strategies (such as breathing exercises and focus shift) and cognitive techniques as the most common ones.

Adverse events

Seven adolescents (23%) reported having experienced some negative event during the course of treatment. These events included increased stress due to the limited time to work with treatment modules (n=4; 13%), increased social anxiety (n=1; 3%), increased panic anxiety (n=1; 3%) and increased depression and negative thoughts (n=1; 3%). Those who reported increased stress and anxiety associated these symptoms with the first weeks of treatment and typically described a decrease as treatment continued. Two adolescents reported that the negative event (increased negative thoughts in one case and increased panic anxiety in the other case) still had some impact on their well-being at the end of treatment.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the feasibility and efficacy of therapist-guided and parent-guided ICBT, supplemented with group exposure sessions, for adolescents with SAD. The results suggest that such a combined treatment format is both feasible and potentially efficacious and that the improvements are maintained at least 6 months beyond treatment termination. Feasibility was indicated by the high proportion of participants who reported satisfaction with the programme and who would recommend it to a peer, as well as by the high attendance rate at group sessions and good completion of online sessions. The results showed substantial reductions of social anxiety symptoms on all clinician-rated, adolescent-rated and parent-rated measures at post-treatment, as well as improvements in secondary outcomes such as overall anxiety and level of functioning. These symptom reductions were maintained or further improved at the 6-month follow-up.

The adolescents completed on average nearly two-thirds of the nine online modules, which is more than in previous studies on ICBT for youth with SAD where participants completed less than half of the modules on average.26 30 It is possible that the face-to-face component (group-based exposure sessions) in the present study influenced the working pace with the internet modules as participants were recommended to complete the preceding modules before attending group sessions. Even if completion of previous modules was not a prerequisite for attendance at group sessions, participants tended to complete them before attending the sessions. Participants also had peer and therapist support in the group on aspects of the internet-delivered modules that they found difficult (eg, designing an idiosyncratic exposure hierarchy), which might have led to more motivation to work with modules after group sessions. It has been proposed that socially anxious children and adolescents have a tendency to avoid practising skills on their own that they have learnt online, such as conducting in vivo exposure.30 It could therefore be hypothesised that the group sessions in this study enhanced the participants’ inclination to practice skills at home as a consequence of being offered intensive therapist guidance and direct feedback during group-based exposure. A majority of the participants completed a large number of online treatment modules and group sessions, which gave them time to conduct a significant amount of exposure (introduced in online module 3) and social skills training (introduced in group session 1 at week four). However, we did not track the number of completed exposure and social skills training exercises in other ways than by proxy, through measuring module completion and group attendance.

Forty-seven per cent of participants no longer met diagnostic criteria for SAD after treatment, a proportion that further increased to 57% at 6-month follow-up. This is in line with levels reported in studies evaluating face-to-face CBT for youth with SAD15 53 59–61 and higher than strictly ICBT for youth with SAD.30 A recent trial of ICBT for youth with SAD reported a relatively limited impact on the clinical diagnosis of SAD (in the two active treatment conditions 12.8% and 14.6% at post-treatment and 29.8% and 35.4% at 6-month follow-up, no longer met diagnostic criteria for SAD),30 and the authors suggest that standalone ICBT might not be enough for youth with SAD.30 It is tempting to attribute the better outcomes in our trial to the addition of group-based exposure sessions to the ICBT protocol, though this hypothesis remains to be formally evaluated. Discrepancies between our and previous results may also be attributable to differences in study samples, study design or other methodological aspects.

Therapists in this study spent less than 20 min per family and week, on the internet-delivered treatment, which is comparable with previous ICBT trials for youth.21 22 Although the group sessions added another 10 min per family and week in the present trial, group exposure-supplemented ICBT should still be considered a time-efficient intervention compared with face-to-face CBT where the therapist time per family and week usually ranges from 45 to 60 min.

Around a fifth of the participants reported a negative event during the course of the treatment. Some of the events were expected, such as increased social anxiety when exposure was initiated. Reports of increased stress were also associated with the first weeks of the treatment and can be interpreted as an initial difficulty combining treatment with other demands such as schoolwork. Two participants reported having experienced some negative events that affected their well-being beyond the treatment termination, but these participants still benefited from treatment.

Overall, the treatment seems feasible and possibly efficacious for adolescents with SAD and their parents, but to be considered for implementation in regular care, an intervention must also be feasible from an organisational point of view. A possible drawback with the addition of group exposure to ICBT is that it limits the flexibility of the intervention. For instance, several patients must be recruited and able to commence treatment at the same time. SAD is a challenging disorder to treat and interventions aspiring to be effective may need to include direct and frequent therapist guidance. However, development of new treatments should consider treatment efficacy and accessibility, flexibility and cost-effectiveness. A possible alternative to group-based exposure sessions is to add other forms of direct communication between patients and ICBT therapists, for example, video conferencing or equivalent, something that future studies should investigate further.

Limitations

Although this feasibility trial has several strengths, some important limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results. Causal inferences of observed changes are not possible due to lack of a control condition. Thus, improvement could be an effect of non-specific factors such as the therapist attention or of the passage of time. However, SAD has been shown to commonly follow a chronic course when left untreated,2 and it is not likely that spontaneous remission would explain a significant part of the improvements in the study. Additionally, results were maintained and slightly improved at follow-up, indicating that treatment gains were stable over time, even after the attention from a therapist had ceased. A small proportion of the participants did seek additional care between post-treatment and 6-month follow-up, which could have affected the results. However, these participants continued to report high levels of social anxiety at follow-up, implying that additional care had limited impact on the long-term outcome. Although social anxiety is generally more common among women, the current sample had an over-representation of girls. The effect of gender on the results in this trial is unclear and may be further analysed in future trials with larger samples.

Another limitation concerns assessment at post-treatment and follow-up. Although attempts to reduce bias were made by having these assessments conducted by clinicians not involved in the treatment, assessors were not blind to the fact that the participant had received treatment.

Conclusions

This is the first study of therapist-guided and parent-guided ICBT supplemented with group exposure for adolescents with SAD. The intervention was highly acceptable to the families and significantly reduced social anxiety symptoms up to 6-month follow-up. Participants were generally satisfied with the treatment, and the completion rates of internet modules and attendance at group sessions were high, indicating that the treatment is feasible and acceptable to the SAD youth population. Furthermore, per-patient therapist time was limited, even considering the time spent on group sessions; thus, ICBT supplemented with group-based exposure sessions might be cost-effective when compared with traditional face-to-face CBT. Further controlled trials are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ulrika Thulin for invaluable help with writing the treatment modules, and Cornelia Hanqvist and Jon Juselius for assisting with providing the treatment.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed by MN, SV, DMC, ES and JH. MN was the project manager in collaboration with JH. MN wrote the treatment modules and provided the treatment in collaboration with JH and SV. All statistical analyses were conducted by JH and MN. MN drafted the manuscript in collaboration with JH. The manuscript was reviewed and revised by SV, ES, DMC, BL and LGÖ. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Stockholm County Council (PPG project20150032; HSNV 140 99; HSN 1011-1176) and the Swedish Research Council and Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte 2014-4052).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (2015/1383-31/2).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arligton, VA: American Psychiatric Pub, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burstein M, He JP, Kattan G, et al. Social phobia and subtypes in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:870–80. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, et al. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. 2015.

- 4.Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, et al. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:903–12. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, DeLeire T, et al. Impact of generalized social anxiety disorder in managed care. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1999–2007. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, et al. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. J Psychiatr Res 2008;42:230–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Psychopathology of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:643–50. 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acarturk C, Smit F, de Graaf R, et al. Economic costs of social phobia: a population-based study. J Affect Disord 2009;115:421–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel A, Knapp M, Henderson J, et al. The economic consequences of social phobia. J Affect Disord 2002;68:221–33. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00323-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scaini S, Belotti R, Ogliari A, et al. A comprehensive meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions for social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 2016;42:105–12. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segool NK, Carlson JS. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments for children with social anxiety. Depress Anxiety 2008;25:620–31. 10.1002/da.20410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilling S, Mayo-Wilson E, Mavranezouli I, et al. Guideline Development Group. Recognition, assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2013;346:f2541 10.1136/bmj.f2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson JL, Rapee RM, Lyneham HJ, et al. Comparing outcomes for children with different anxiety disorders following cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav Res Ther 2015;72:30–7. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Behavioral treatment of childhood social phobia. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:1072–80. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Sallee FR, et al. SET-C versus fluoxetine in the treatment of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:1622–32. 10.1097/chi.0b013e318154bb57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency and comorbidity of social phobia and social fears in adolescents. Behav Res Ther 1999;37:831–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wittchen HU, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidity. Psychol Med 1999;29:309–23. 10.1017/S0033291798008174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:32–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedman E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2011;49:729–36. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenhard F, Andersson E, Mataix-Cols D, et al. Therapist-guided, internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:10–19. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.09.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenhard F, Vigerland S, Andersson E, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e100773 10.1371/journal.pone.0100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedman E, Andersson G, Ljótsson B, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. PLoS One 2011;6:e18001 10.1371/journal.pone.0018001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.March S, Spence SH, Donovan CL. The efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disorders. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:474–87. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tillfors M, Andersson G, Ekselius L, et al. A randomized trial of Internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder in high school students. Cogn Behav Ther 2011;40:147–57. 10.1080/16506073.2011.555486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan CL, March S. Online CBT for preschool anxiety disorders: a randomised control trial. Behav Res Ther 2014;58:24–35. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vigerland S, Ljótsson B, Thulin U, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for children with anxiety disorders: A randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2016;76:47–56. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spence SH, Donovan CL, March S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of online versus clinic-based CBT for adolescent anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:629–42. 10.1037/a0024512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spence SH, Donovan CL, March S, et al. Generic versus disorder specific cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder in youth: A randomized controlled trial using internet delivery. Behav Res Ther 2017;90:41–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sethi S. Treating youth depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial examining the efficacy of computerised versus face-to-face cognitive behaviour therapy. Aust Psychol 2013;48:249–57. 10.1111/ap.12006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sethi S, Campbell AJ, Ellis LA. The use of computerized self-help packages to treat adolescent depression and anxiety. J Technol Hum Serv 2010;28:144–60. 10.1080/15228835.2010.508317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Holmström A, et al. Internet-based self-help with therapist feedback and in vivo group exposure for social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:677–86. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathiasen K, Andersen TE, Riper H, et al. Blended CBT versus face-to-face CBT: a randomised non-inferiority trial. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:432 10.1186/s12888-016-1140-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guy W. Clinical global impression scale The ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology-revised volume DHEW publ no ADM. 76 Maryland: National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.). Psychopharmacology Research Branch. Division of Extramural Research Programs, 1976:218–22. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albano A, Silverman W. The anxiety disorders interview schedule for children for dsm-iv: clinician manual(child and parent versions). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:1228–31. 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. A new inventory to assess childhood social anxiety and phobia: the social phobia and anxiety inventory for children. Psychol Assess 1995;7:73–9. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, et al. Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in generalized social phobia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:1058–67. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hedman E, Mörtberg E, Hesser H, et al. Mediators in psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: individual cognitive therapy compared to cognitive behavioral group therapy. Behav Res Ther 2013;51:696–705. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, et al. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav Res Ther 2000;38:835–55. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, et al. The Work and social adjustment scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:461–4. 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mataix-Cols D, Cowley AJ, Hankins M, et al. Reliability and validity of the work and social adjustment scale in phobic disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2005;46:223–8. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, et al. KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2005;5:353–64. 10.1586/14737167.5.3.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouwmans C, De Jong K, Timman R, et al. Feasibility, reliability and validity of a questionnaire on healthcare consumption and productivity loss in patients with a psychiatric disorder (TiC-P). BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:1 10.1186/1472-6963-13-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis FD. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 1989;13:319–40. 10.2307/249008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonnert M, Olén O, Lalouni M, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:S99–S100. 10.1016/S0016-5085(16)30443-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lenhard F, Vigerland S, Andersson E, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e100773 10.1371/journal.pone.0100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vigerland S, Thulin U, Ljótsson B, et al. Internet-delivered CBT for children with specific phobia: a pilot study. Cogn Behav Ther 2013;42:303–14. 10.1080/16506073.2013.844201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther 1997;35:741–56. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. 41 Newyork: The Gilford Press, 1995:00022–3. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albano AM, Marten PA, Holt CS, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for social phobia in adolescents. A preliminary study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183:649–56. 10.1097/00005053-199510000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albano AM, DiBartolo PM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for social phobia in adolescents: stand up, speak outtherapist guide. London, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ, Martin LY, et al. Reliability of anxiety assessment. I. Diagnostic agreement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:1093–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:310–7. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayward C, Varady S, Albano AM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia in female adolescents: results of a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39:721–6. 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spence SH, Donovan C, Brechman-Toussaint M. The treatment of childhood social phobia: the effectiveness of a social skills training-based, cognitive-behavioural intervention, with and without parental involvement. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000;41:713–26. 10.1111/1469-7610.00659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Öst LG, Cederlund R, Reuterskiöld L. Behavioral treatment of social phobia in youth: does parent education training improve the outcome? Behav Res Ther 2015;67:19–29. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.