Abstract

Background:

Epidural anesthesia has been well established as a safe and effective technique not only for perioperative anesthesia but also for postoperative analgesia. Various adjuvants have been added to local anesthetic agent in an effort to prolong this duration.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to compare and evaluate the anesthesia and analgesic property of ropivacaine to its combination with clonidine for lower limb orthopedic surgery under epidural.

Materials and Methods:

In a prospective, randomized, double-blind study, eighty adult patients undergoing lower limb surgeries received either 0.75% ropivacaine or 75 μg clonidine with 0.75% ropivacaine through epidural route. Patients were compared for hemodynamic variability, quality of motor and sensory block, intra- and post-operative analgesia, and the side effects associated.

Statistical Analysis:

Data analysis was done by Student's paired t-test, Chi-square test, and Mann–Whitney test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The time taken for onset of the motor as well as the sensory block was significantly shorter in ropivacaine with clonidine group as compared to ropivacaine alone group. Mean duration of analgesia was significantly higher in patients who received clonidine as an adjunct (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference observed in the incidence of hemodynamic changes or side effects.

Conclusion:

The study demonstrated that use of clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine through epidural route provides a hemodynamically stable, faster, and prolonged epidural block and a longer analgesic effect as compared to ropivacaine alone.

Keywords: Clonidine, epidural, ropivacaine

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, epidural anesthesia has been well established as a safe and effective technique for not only perioperative anesthesia but also for postoperative analgesia. There has been an upsurge of interest in recent times in newer agents and adjuncts which can be employed for epidural anesthesia that may offer quicker recovery and earlier ambulation along with fewer side effects.

Ropivacaine, a long-acting amide local anesthetic, is an optically active pure S-enantiomer of propivocaine.[1] Numerous comparative studies between ropivacaine and bupivacaine suggested that ropivacaine produces less cardiac as well as central nervous system toxic effects and lesser motor block.[2,3] This favorable clinical profile prompted many clinicians to switch from bupivacaine to ropivacaine for the neural blockade. Ropivacaine's latency of sensory analgesia is approximately two-thirds that of bupivacaine; therefore, it was not effective in prolongation of postoperative analgesia.[4]

Clonidine, a α-2 adrenergic agonist, acts on inhibitory α-2 adrenergic receptors to reduce central neural transmission in the spinal neurons.[5] Its analgesic potency has been described as being comparable to epidural-administered morphine.[6] The coadministration of clonidine and local anesthetic produces better analgesia than either drug alone.[7]

There is only a few literature available comparing addition of clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine; hence, there is a need to fill this void based on empirical evidence. Thus, the present study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of epidural clonidine as an adjuvant with ropivacaine compared to ropivacaine alone in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgery.

Aims and objective

To evaluate and compare the hemodynamic stability of patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgery using ropivacaine with clonidine to that of ropivacaine alone.

To evaluate and compare the time taken to achieve an optimum level of sensory and motor block, duration of block achieved and duration of postoperative analgesia in both the group.

To evaluate and compare the side effects if any.

SUBJECTS AND METHOD

After obtaining approval by the Institutional Ethical Committee, a randomized, double-blinded, prospective, observational study was done. Inclusion criteria were adult patients aged 18–70 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical Status I or II, either sex, presenting for elective lower limb surgeries. Exclusion criteria were the patient refusal, history of allergy or sensitivity to any of the study drug, ASA Grade III and IV, morbid obesity, bleeding disorders, infections and/or severe psychiatric disorder, patients with significant cardiovascular disease, renal failure, hepatic dysfunction, and chronic pulmonary disease.

Eighty adult patients of either sex were randomized to one of the two groups of forty patients each.

Group 1: Received 20 ml 0.75% ropivacaine through epidural route

Group 2: Received epidural 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine. with 75 μg clonidine.

Methods

All patients were kept nil per oral for at least 6 h, premedicated with oral ranitidine 150 mg, alprazolam 0.25 mg, and metoclopramide 10 mg the night before surgery. Intravenous line secured, Ringer's lactate solution (10 ml/kg) was infused for 15 min before the initiation of the procedure. Noninvasive monitors connected and baseline values of heart rate (HR), blood pressure, and oxygen saturation were recorded before the procedure. Electrocardiogram monitoring was enabled.

Before the commencement of anesthesia, patients were instructed on the methods of sensory or motor assessments. After proper positioning under strict aseptic precaution, L3-L4 epidural space was identified. Local infiltration was done using 2 ml of 2%xylocaine at the puncture site. 18 Gauze Tuohy's needle was inserted and epidural space was confirmed by loss of resistance method. Group I and II patients received the epidural anesthetics as they have been scheduled. The patient and observing anesthesiologist were blinded to the drug group. After establishing adequate sensory and motor blockade, surgeons were asked to proceed with the surgery.

The baseline value of vital signs (blood pressure BP, HR, SpO2) was recorded before performing the procedure and once in every 5 min inside the operation theater, then after every 15 min in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit till the recovery of sensory and motor function. Sensory block was assessed by pinprick sensation using a hypodermic needle. Motor function was assessed by modified Bromage scale. Bromage scale for the lower extremities consists of the following four scores (0 = no motor block, 1 = unable to raised extended legs, 2 = unable to flex knees, 3 = unable to flex ankle joint). Postoperative pain was assessed using visual analog scale.

The duration of sensory or motor blockade was defined as the interval from intrathecal administration to the point of complete resolution of the sensory block or to the point in which the Bromage score was back to zero, respectively. The measurements were obtained at baseline, 5, 10, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, and after 4 h intervals following the block. Adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, and shivering were also documented and managed symptomatically.

The statistical analysis was done using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) Version 15.0. The values were represented in number (%) and mean ± standard deviation. Results were analyzed by Student's paired t-test, Chi-square test, and Mann–Whitney test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

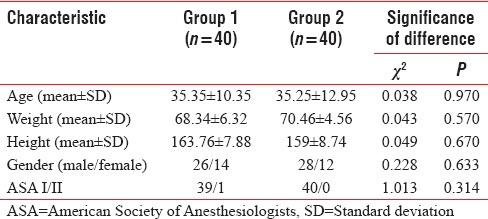

Both the groups were comparable with regard to age, weight, height, sex, and ASA status [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

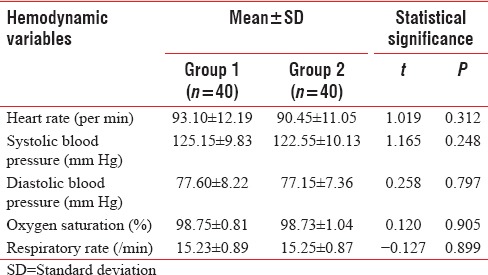

At baseline, both the groups were matched hemodynamically and did not show a significant intergroup difference for any of the parameters (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline hemodynamic variables in study population

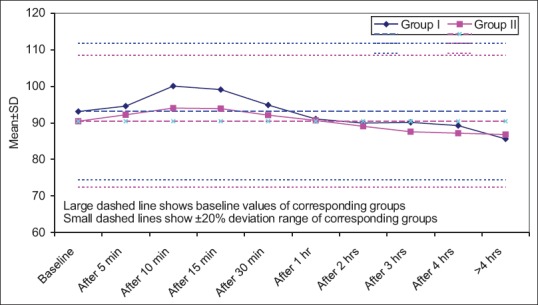

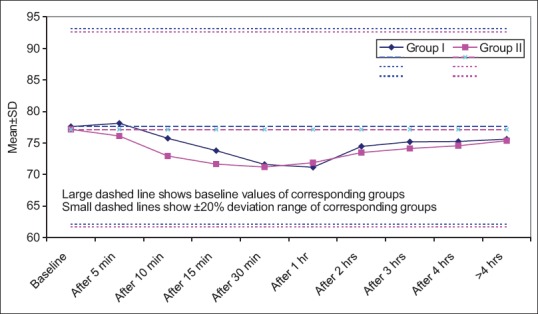

Statistically no significant difference was observed in HR between two groups for most of the study period. Only significant differences between two groups were observed at 10 min and 15 min intervals only. At both the time intervals, Group I had significantly higher mean value as compared to Group II (P < 0.05) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Statistically no significant difference was observed in heart rate between two groups for most of the study period. Only significant differences between two groups were observed at 10 and 15 min intervals only. At both the time intervals, Group I had significantly higher mean value as compared to Group II (P < 0.05)

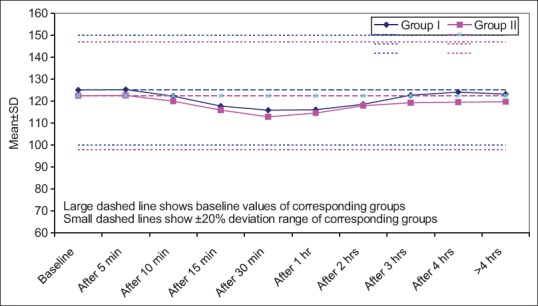

Statistically no significant difference was observed in systolic blood pressure between two groups for most of the study period. Only significant differences between two groups were observed at 3 and 4 h interval only. At both the time intervals, Group I had significantly higher mean value as compared to Group II (P < 0.05) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Statistically no significant difference was observed in systolic blood pressure between two groups for most of the study period. Only significant differences between two groups were observed at 3 and 4 h intervals only. At both the time intervals, Group I had significantly higher mean value as compared to Group II (P < 0.05)

With regard to diastolic blood pressure, Group I had higher mean values as compared to Group II, at all the time intervals except at 1 h. However, at none of the time intervals during the study, the difference between two groups was statistically significant (P > 0.05) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

With regard to diastolic blood pressure, Group I had higher mean values as compared to Group II, at all the time intervals except at 1 h. However, at none of the time intervals during the study, the difference between two groups was statistically significant (P > 0.05)

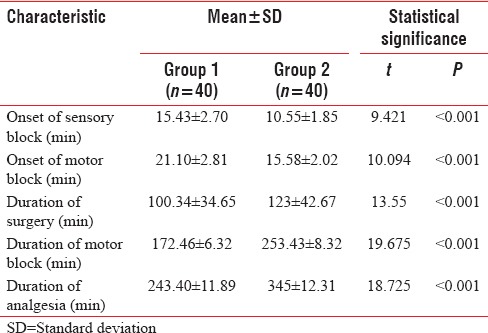

The time taken for onset of motor as well as sensory block was significantly shorter in Group II as compared to Group I. Mean duration of analgesia was significantly higher in Group II as compared to Group I (P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Onset time for sensory block and motor block with duration of surgery and analgesia in two study groups

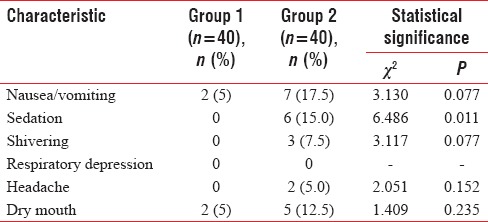

Although incidence of side effects was higher in Group 2 as compared to Group 1, yet the difference between two groups was found to be significant only for sedation (P = 0.011) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Side effects

DISCUSSION

Epidural, a versatile anesthetic technique, can be used as an anesthetic as an analgesic adjuvant to general anesthesia and for postoperative analgesia in procedures involving lower limbs, perineum, pelvis, and abdomen.[3] The present study was planned to evaluate the efficacy of clonidine with ropivacaine (RC) as compared to ropivacaine alone (R) in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgery.

In recent years, ropivacaine, an enantiomer of bupivacaine, has increasingly replaced bupivacaine because of its similar analgesic properties, lesser motor blockade, and decreased propensity of cardiotoxicity.[8] The attempts to improve the quality of block and to enhance the postoperative analgesic effect with the addition of adjuvants is increasing in the current practice.

Clonidine, an α-2 adrenergic agonist, which produces analgesia through a nonopioid mechanism, is used as an adjuvant in regional anesthesia in various settings.[9] Clonidine augments the action of local anesthetics in regional blockades by interrupting the neural transmission of painful stimuli in Aδ and C fibers as well as augments the blockade of local anesthetic agents by increasing the conductance of K+ ions in nerve fibers. It also exerts a vasoconstricting effect on smooth muscles, which results in a decreased absorption of the local anesthetic drug and eventually prolongs the duration of analgesia.[10,11] Keeping this pharmacological interactions in mind, we have tried to use clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in lower limb orthopedic surgeries.

Clonidine has a potent regressive effect on HR within 15–90 min of epidural administration, that is why, in the present study, a significantly lower mean HR in RC group as compared to R alone was observed between 15 and 30 min intervals. The results in the present study were similar to those observed by Bajwa et al.[12] who showed similar variations in HR but at different time intervals. In their study, significant differences in mean HR between two groups were observed from 20 min of administration and continued till 120 min. In the present study, such difference was observed at 15 min interval only. For the remaining part of our study, the results were similar to those obtained by Laha et al.[13] who observed no significant difference in HR between ropivacaine alone and ropivacaine with clonidine.

Clonidine suppresses sympathetic outflow resulting in lower blood pressure. Addition of clonidine either as a fixed dose or as an infusion has been shown to have a lowering effect on arterial pressure as observed in the present study.[14] Despite reduction in mean blood pressure levels, no event of hypotension was noticed in any group thus highlighting that the given dosage of clonidine did not reduce the arterial pressure substantially. Moreover, there are limited reports suggestive of hypotensive effect of clonidine when used as an epidural adjuvant.

With respect to onset of motor and sensory block, both the blocks were achieved earlier in ropivacaine with clonidine (RC) group as compared to ropivacaine alone (R). Similarly, regression of sensory and motor blockade was longer in RC Group compared to R group. The results are in agreement with the study of Bajwa et al.[10] and Gecaj-Gashi et al.[15] who observed that addition of clonidine reduces the onset time for blocks and enhances the duration of block when added to ropivacaine.

Duration of analgesia was better in Group II (RC) as compared to Group I (R). Coadministration of clonidine with local anesthetic has been documented to have better analgesia than either drug alone[16] and observations in the present study support the same. Adding clonidine as an adjuvant in the epidural space has an additive effect, which results in a lower dose of narcotic necessary for optimal pain control.[17]

The present study did not have any severe side effect. Dry mouth and nausea/vomiting were the most common side effects observed in all the three groups. None of the patient had respiratory depression. Although side effects were minimum in ropivacaine alone group yet except for sedation, no significant intergroup difference was observed. The sedative effect of clonidine has been discussed in solitary use as well as when used as adjuvant.[18]

The findings in the present study show that ropivacaine in combination with clonidine provides a hemodynamically stable, faster, and prolonged epidural block and a longer analgesic effect as compared to ropivacaine alone.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McConachie I, McGeachie J, Barrie J. Regional anaesthetic techniques. In: Thomas EJ, Knight PR, editors. Wylie and Churchill Davidson's – A Practice of Anesthesia. Vol. 37. London: Arnold; 2003. pp. 599–612. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant CR, Checketts MR. Analgesia for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: The role of regional anaesthesia. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2008;8:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser L. Epidural anesthesia. Update Anesthesiol. 2009;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casati, Fanelli G, Aldegheri G, Berti M, Colnaghi E, Cedrati V, Torri G. Interscalene brachial plexus anaesthesia with 0.5%, 0.75% or 1% ropivacaine: a double-blind comparison with 2% mepivacaine. Br JAnaesth. 1999;83:872–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.6.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanelli G, Casati A, Garancini P, Torri G. Nerve stimulator and multiple injection technique for upper and lower limb blockade: Failure rate, patient acceptance, and neurologic complications. Study Group on Regional Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:847–52. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199904000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamsen A, Gordh T. Epidural clonidine produces analgesia. Lancet. 1984;2:231–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acalovschi I, Bodolea C, Manoiu C. Spinal anesthesia with meperidine. Effects of added alpha-adrenergic agonists: Epinephrine versus clonidine. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:1333–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199706000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClellan KJ, Faulds D. Ropivacaine: An update of its use in regional anaesthesia. Drugs. 2000;60:1065–93. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi Y, Maze M. Alpha 2 adrenoceptor agonists and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:108–18. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J. Comparison of epidural ropivacaine and ropivacaine clonidine combination for elective cesarean sections. Saudi J Anaesth. 2010;4:47–54. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.65119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mogensen T, Eliasen K, Ejlersen E, Vegger P, Nielsen IK, Kehlet H. Epidural clonidine enhances postoperative analgesia from a combined low-dose epidural bupivacaine and morphine regimen. Anesth Analg. 1992;75:607–10. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199210000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bajwa SJ, Kaur J, Bajwa SK, Bakshi G, Singh K, Panda A. Caudal ropivacaine-clonidine: A better post-operative analgesic approach. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:226–30. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.65368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laha A, Ghosh S, Das H. Comparison of caudal analgesia between ropivacaine and ropivacaine with clonidine in children: A randomized controlled trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012;6:197–200. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.101199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topcu I, Erincler T, Tekin S, Karaer O, Isik R, Sakarya M. The comparison of efficiency of ropivacaine and addition of fentanyl or clonidine in patient controlled epidural analgesia for labour. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2006:11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gecaj-Gashi A, Terziqi H, Pervorfi T, Kryeziu A. Intrathecal clonidine added to small-dose bupivacaine prolongs postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing transurethral surgery. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:25–9. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syal K, Dogra R, Ohri A, Chauhan G, Goel A. Epidural labour analgesia using Bupivacaine and Clonidine. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:87–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Kock M, Crochet B, Morimont C, Scholtes JL. Intravenous or epidural clonidine for intra-and postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:525–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199309000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamadarkhana S, Gopal S. Clonidine in adults as a sedative agent in the Intensive Care Unit. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26:439–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]