Abstract

Background:

Postoperative analgesia after cesarean section poses unique clinical challenges to anesthesiologist. Intrathecal buprenorphine is a promising drug for postoperative analgesia.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of two doses of buprenorphine (45 μg and 60 μg) as an adjuvant to hyperbaric bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in cesarean section.

Setting and Design:

Prospective randomized double-blind controlled study involving ninety parturients posted for elective cesarean section under subarachnoid block.

Materials and Methods:

Group A (n = 30) received 1.8 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 45 μg buprenorphine, Group B (n = 30) received 1.8 ml 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 60 μg buprenorphine, Group C (n = 30) received 1.8 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 0.2 ml normal saline, respectively. Following parameters were observed: onset and duration of sensory block, postoperative pain scores based on visual analog scale (VAS), rescue analgesic requirement, and maternal and neonatal side effects if any.

Statistical Analysis:

Unpaired t-test and Chi-square test were used.

Results:

Duration of postoperative analgesia was significantly prolonged in Groups A and B in comparison to Group C and it was longest in Group B. Rescue analgesic requirement and VAS score were significantly lower in the buprenorphine groups. No major side effects were observed.

Conclusion:

Addition of buprenorphine to intrathecal bupivacaine prolonged the duration and quality of postoperative analgesia after cesarean section. Increasing the dose of buprenorphine from 45 μg to 60 μg provided longer duration of analgesia without increase in adverse effects.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, buprenorphine, cesarean, intrathecal, postoperative analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Pain has been a scourge for humankind and much effort has been done to understand it and thereby control it. Postoperative pain by virtue of its unique transient nature is more amenable to therapy. The rate of cesarean deliveries has increased globally over recent years. Adequate postoperative pain relief after cesarean section avoids the adverse effects of pain on various systems in the mother and facilitates early mobilization and better nursing of the baby. It is inevitable that the mode of analgesia should be safe and effective, which will not interfere with the mothers’ ability to take care of her baby along with zero adverse effects to the newborn. Eisenach et al. found 2.5 times increased risk of persistent pain and 3.0 times increased risk of postpartum depression in women experiencing severe acute postpartum pain.[1] Subarachnoid block (SAB) has become the preferred anesthetic technique for patients undergoing elective cesarean delivery.[2] Opioids remain the mainstay among the various adjuvants to local anesthetics (LAs) in SAB primarily by virtue of its various properties such as reducing the dose of LA, minimizing side effects, and prolonging the duration of anesthesia.[3] American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommends neuraxial opioids over intermittent administration of parenteral opioids for postoperative analgesia after neuraxial anesthesia for caesarean section.[4] As smaller doses are used intrathecally, neonatal drug transfer is negligible compared to epidural or parenteral opioids. Although morphine is the gold standard for postoperative analgesia, its use is associated with inherent side effects such as delayed respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and pruritus. Moreover, developing countries face a limited supply of preservative-free preparation.

Buprenorphine is an agonist-antagonist opioid, about thirty times more potent than morphine. It is a centrally acting lipid soluble analog of the alkaloid thebaine with both spinal and supraspinal components of analgesia.[5,6] In addition, it has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression but not on analgesia.[7] The antihyperalgesic property of buprenorphine helps in preventing central sensitization.[5] Its high lipid solubility, high affinity for opioid receptors, and long duration of action makes buprenorphine a good choice as an adjuvant to intrathecal LA for managing moderate to severe postoperative pain.[8,9] Buprenorphine is readily available as a preservative-free preparation which is compatible with the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Intrathecal doses (30 μg–150 μg) are much smaller than parenteral doses and are known to prolong analgesia without sensory or motor blockade.[3,8,9] Being more lipophilic than morphine, buprenorphine has low medullary bioavailability after neuraxial administration so that the occurrence of side effects is lesser, making it an attractive alternative.[5,8] Several studies have demonstrated efficacy of buprenorphine as an adjuvant to LA in SAB; however, optimal dose which provides a balance between analgesia and adverse effects has not been described and also there are very limited studies in patients for cesarean section. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of two doses of buprenorphine (45 μg and 60 μg) as an adjuvant to hyperbaric bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in cesarean section. The side effect profile of neuraxial buprenorphine on the mother and the newborn in the early postoperative period was also assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at a tertiary care center after obtaining approval from the Institution Ethics Committee and written informed consent from all patients who participated in the study. This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled study.

Ninety ASA physical status Class I and Class II parturients posted for elective cesarean section between the age of 20 and 35 years, with height of 145–170 cm and body weight 45–75 kg were selected for this study. The computer-generated simple random sampling procedure was used to allocate the subjects into three Groups A, B, C of 30 each. Exclusion criteria were coexisting systemic illness, emergency surgery, history of allergy to LAs or opioids, patient refusal, fetal distress, or any contraindication to SAB. Those with failed or partial block were excluded from the study.

A thorough preoperative assessment was done on the day before surgery to exclude any systemic illness and to select patients according to the criteria. Body weight, height, and vitals were recorded. All patients were advised overnight fasting. Aspiration prophylaxis was done with oral ranitidine 150 mg on the night before surgery and in the morning along with metoclopramide 10 mg. Procedure was explained to the patient and visual analog scale (VAS) discussed. Patients were brought to theater in the left lateral position. Monitors were attached and oxygen was administered with simple face mask throughout the surgery. Intravenous access was secured using an 18-gauge cannula sited in the nondominant hand under local anesthesia and preloading was done with 20 ml/kg normal saline. After bladder catheterization, patients were turned to lateral position. Under strict aseptic precautions, SAB was performed at L3–L4 interspace using a 25-gauge spinal needle by midline approach. After clear CSF tap, the drug was injected into the subarachnoid space.

Group A received 1.8 ml (9 mg) of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 45 μg buprenorphine

Group B received 1.8 ml (9 mg) of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with 60 μg buprenorphine

Group C (control) received 1.8 ml (9 mg) of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine to which 0.2 ml of sterile normal saline was added.

Buprenorphine was taken in tuberculin syringe so as to add it precisely.

The study medication was administered by an anesthesiologist not involved in the care of patient or collection of data. The principal investigator blind to the identity of study medication, monitored and managed the patients, and collected data.

After the subarachnoid injection, patients were immediately turned to the supine position and a wedge was kept under the right buttock. Heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration were monitored every 2 min for 30 min and every 5 min thereafter. Surgery was started when the sensory level reached T4 level (assessed with pinprick) and this was taken as the time of onset of analgesia. Intraoperative fluid maintenance was done with normal saline. After delivery of the baby, 10 units of oxytocin was administered as an infusion in normal saline. Neonatal status was assessed by Apgar scores at 1 min and 5 min after delivery. Sensory level was rechecked during the procedure and peak sensory level attained was noted. The total duration of surgery was noted and the time of completion of surgery was taken as the postoperative 0 h. No other analgesics or sedatives were given intraoperatively. Postoperatively, pulse rate, blood pressure, and respiration were monitored every 15 min for 2 h and then hourly for 24 h.

Postoperative analgesia was assessed hourly using VAS. The duration of postoperative analgesia was calculated as the time interval between the completion of surgery to the appearance of pain corresponding to VAS score of 4. Rescue analgesia was with tramadol 1 mg/kg along with metoclopramide 10 mg given intramuscularly (IM). The number of rescue analgesic doses needed was noted. Patients with inadequate pain relief even after tramadol were given diclofenac 75 mg IM as additional analgesic. Patients were evaluated for efficacy of postoperative analgesia by analyzing the maximum pain score attained using VAS during the 24 h period. Pain both at rest and movement was assessed.

Every hour, patients were monitored for the appearance of sedation and respiratory depression. Respiratory depression was taken as respiratory rate <10/min. Sedation was assessed using sedation scoring system; 0: none (awake and alert), 1: mild (drowsy but easy to arouse), 2: moderate (frequently drowsy but still fully arousable), 3: severe (difficult to arouse). The highest score attained was noted.

Other side effects such as postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and pruritus were watched for. As bladder was catheterized, urinary retention was not looked into. Patients who had nausea or vomiting were treated with ondansetron 4 mg intravenous. Pruritus was treated with pheniramine maleate.

The data collected were entered into a master chart and necessary statistical tables were constructed. The statistical constants such as arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and percentage were computed to get valid inference about the data for comparison. Unpaired t-test and Chi-square test were used to test the significance of difference between the groups. Peak sensory levels, maximum pain score, and side effects were analyzed using Chi-square test and the rest using unpaired t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

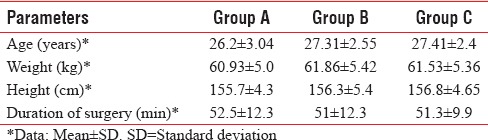

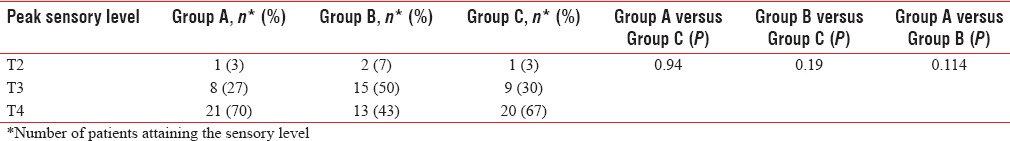

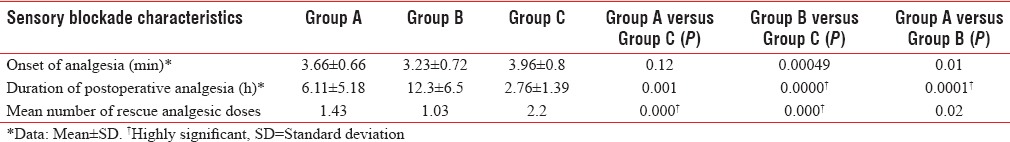

All three groups were comparable with respect to age, weight, height, and duration of surgery as P was > 0.05 [Table 1]. The peak sensory level was comparable among the three groups [Table 2]. There was a significant difference in the onset of analgesia in Group B when compared to Group A and C. Onset of analgesia was comparable between Group A and Group C [Table 3].

Table 1.

Demographic data and duration of surgery

Table 2.

Peak sensory level

Table 3.

Sensory blockade characteristics

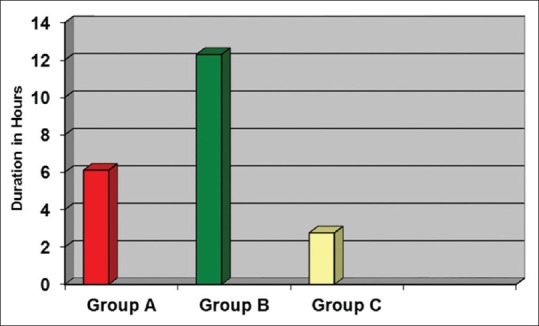

Duration of postoperative analgesia was significantly longer in Group A and Group B when compared to Group C [Figure 1]. There was a significant difference in postoperative analgesia between Group A and Group B also [Table 3]. Analgesic requirement was less in Group A and Group B compared to control group. There was statistically significant difference in analgesic requirement between Group A and B. Two patients in Group A and five patients in Group B did not require any analgesic during the study period [Table 3].

Figure 1.

Duration of postoperative analgesia

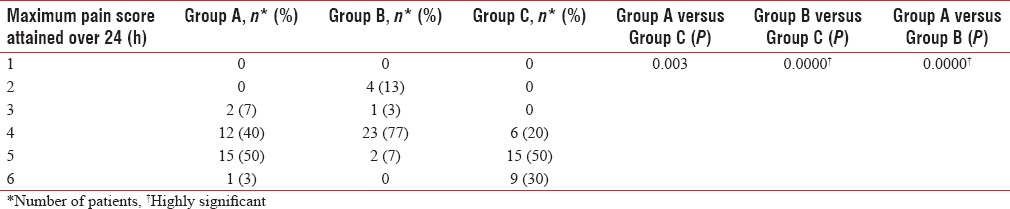

None in Group B and only three patients in Group A required additional analgesics (injection diclofenac), whereas nine patients (30%) in the control group required additional analgesics. Maximum pain scores were significantly lower in Group A and B compared to the control group. Group B had lower pain scores compared to both Group A and C [Table 4]. Seventy-seven percent of patients in Group B had a maximum VAS score of only 4.

Table 4.

Maximum pain score

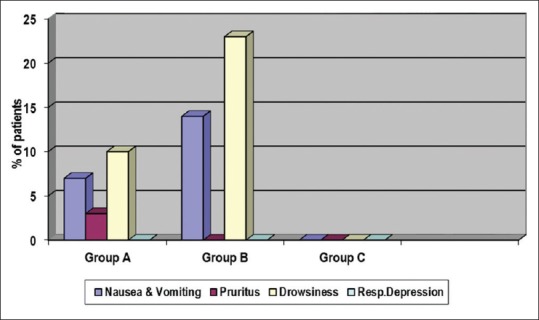

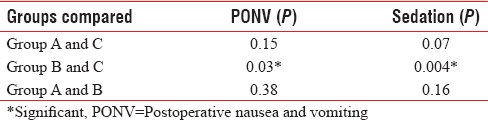

Apgar score of all babies was more than seven in all three groups. Incidence of sedation and PONV was significantly more in Group B when compared to Group C. In Group B, sedation and PONV were seen in 23.3% and 13.3%, respectively [Figure 2]. None of the patients had sedation score more than 1. Pruritus was seen only in one patient and that was in Group A. It was relieved by giving injection pheniramine maleate 1 ml intravenously. Naloxone was not needed. None developed respiratory depression. Respiratory rate was more than 12 per min in all patients in the study groups. The incidence of side effects was similar in the study groups [Table 5]. No side effects were seen in the control group.

Figure 2.

Side effects

Table 5.

Comparison of incidence of side effects between groups

DISCUSSION

Pain relief is the most gratifying service that can be offered to any patient. Postoperative analgesia after cesarean section poses unique clinical challenges to anesthesiologist as it should allow early ambulation of the mother to prevent thromboembolic episodes and ensure bonding with the baby. It should have no undesirable effects on the mother or newborn. SAB with LA alone provides limited postoperative analgesia. Opioid adjuvants can subjugate this limitation. Buprenorphine is a highly potent and lipophilic agonist-antagonist opioid with long duration of action which makes it an excellent choice for postoperative analgesia.[5,10] High lipid solubility and high-molecular weight limit rostral spread of buprenorphine reducing the incidence of adverse effects compared to morphine. Different doses of buprenorphine ranging from 30 μg to 150 μg have been used as adjuvant to LA in SAB.[11,12,13] No ideal dose has been described that can produce postoperative analgesia with minimum side effects.

This study was done mainly to assess efficacy of two doses of intrathecal buprenorphine for postoperative pain relief in cesarean section and involved 90 patients divided into three groups of 30 each. The groups were comparable with respect to demographic characteristics.

Postoperative analgesia

The mean duration of postoperative analgesia was 6.1 h for 45 μg group and 12.3 h for 60 μg group. There was significantly prolonged analgesia in both study groups when compared to control group. The mean duration of analgesia was highly significant in 60 μg group compared to both the other groups.

A similar study was conducted by Dixit, in cesarean section with 60 patients in two groups. In the control group, he used 1.7 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine and in the study group, bupivacaine with 60 μg buprenorphine.[14] The 60 μg buprenorphine group had a mean duration of analgesia of 8.2 h. In the study by Capogna et al., patients who received 45 μg buprenorphine had a mean duration of analgesia of 7.1 h.[12] Fifty percent patients had analgesia at 6 h which declined to 16% at 20 h in the study conducted by Ipe et al. using 150 μg buprenorphine.[15] Results in the present study are comparable with the above studies. This shows that addition of buprenorphine to intrathecal bupivacaine produces prolonged duration of analgesia which is dose-dependent. This is due to its great affinity for mu receptors and its slow dissociation from the receptors.

Rescue analgesic requirement was less in 45 μg group and 60 μg group compared to control group, which was statistically significant. In the control group, analgesic requirement was more than twice that in 60 μg group. Mean number of rescue analgesic doses required were 1.43, 1.03, and 2.2 for 45 μg, 60 μg, and control groups, respectively. An increase in dose of buprenorphine from 45 μg to 60 μg significantly reduced the rescue analgesic requirement. Singh et al. also found a significantly lower requirement of rescue analgesic with addition of 60 μg buprenorphine to intrathecal ropivacaine.[8]

Patients were evaluated for efficacy of postoperative analgesia by analyzing the maximum pain score attained using VAS during the 24 h period. Maximum pain scores were significantly lower in buprenorphine groups compared to control group. Eighty percent of patients in control group had VAS scores >4. Lowest VAS score of two was seen only in 60 μg group. Quality of analgesia as assessed by VAS score was significantly better with an increase in dose of buprenorphine.

Among the groups, 60 μg group alone had a statistically significant rapid onset of block. The rapid onset may be due to its high lipid solubility and high affinity for opioid receptors. In the study by Dixit, onset of analgesia in the study group was also faster than control.[14] The peak sensory level of block was comparable among the three groups. This may be because the same dose of bupivacaine (9 mg) was used in all three groups and also the volume of drug administered was almost same. Samal et al. reported elevated sensory levels with the addition of 150 μg buprenorphine intrathecally.[11]

Side effects

Of all the side effects evaluated, sedation was the most common one seen in the study groups. Although the incidence of sedation was significant in the 60 μg group, all patients were easily arousable (sedation score 1). Mild sedative effect which is desirable in the perioperative period was also noted by Dixit in his study.[14] Incidence of PONV was more with 60 μg buprenorphine, which was statistically significant when compared with control group. There was no significant difference in the incidence of side effects when comparing 45 μg and 60 μg buprenorphine groups. Capogna et al. also noted PONV in 36% patients receiving 30 μg buprenorphine and in 46% patients receiving 45 μg of buprenorphine in contrast to lower incidence in our study.[12] Higher incidence reported may be explained by the elderly population involved. Ipe et al. reported a lower incidence of 20% in cesarean patients even with 150 μg buprenorphine.[15]

None of our patients developed respiratory depression. In the study by Ipe et al. in cesarean section, respiratory depression was not observed even with 150 μg intrathecal buprenorphine.[15] Being more lipophilic than morphine, rostral spread of intrathecal buprenorphine and therefore the risk of respiratory depression is much less.[16,17,18] Addition of 60 μg buprenorphine produced increased incidence of minor side effects when compared to control group; however, addition of 45 μg buprenorphine did not produce significant increase in side effects compared to control group. Pruritus, though more likely in obstetric patients receiving neuraxial opioids, was observed only in one patient in the study group.[15]

Apgar score of all babies delivered was within normal limits. None of them required any resuscitative measures. Neonatal outcome was shown to be good in several similar studies.[14,15] This shows that buprenorphine can be safely used intrathecally for cesarean section without any adverse outcome on the baby. Our study has resulted in addition of 60 μg buprenorphine to hyperbaric bupivacaine in every scheduled cesarean section in ASA physical status Class I and Class II patients under SAB in our institution.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we chose a maximum dose of 60 μg of buprenorphine though higher doses might have resulted in further prolongation of analgesia. However, higher doses have been reported to cause more adverse effects which were undesirable in this particular study population. We also did not study the effect of adding buprenorphine on hemodynamic variables and characteristics of motor block during intraoperative period. This is accountable as we preferred to concentrate on postoperative analgesia. Neonatal effects were assessed using Apgar score though umbilical cord blood gas analysis would have been less subjective.

SUMMARY

Addition of buprenorphine to intrathecal bupivacaine prolonged the duration and quality of postoperative analgesia without producing any major side effect. The maximum duration of analgesia and hence decreased analgesic requirement were obtained with 60 μg buprenorphine. Addition of buprenorphine did not have any adverse outcome on the baby as assessed by Apgar score.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that addition of buprenorphine to hyperbaric bupivacaine provides postoperative analgesia after cesarean section without significant maternal and neonatal side effects. Increasing the dose of buprenorphine from 45 μg to 60 μg produced significantly prolonged duration of analgesia without increase in the incidence of adverse effects. Hence, addition of 60 μg buprenorphine to intrathecal bupivacaine is a safe, easy, and effective method of postoperative analgesia after cesarean section.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Staff, Department of Anesthesiology, Government Medical College, Kozhikode.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, Lavand’homme P, Landau R, Houle TT. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsen LC. Anesthesia for cesarean delivery. In: Chestnut DH, Polley LS, Tsen LC, Wong CA, editors. Chestnut's Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 521–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan FA, Hamdani GA. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and buprenorphine in urological surgery. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:277–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:843–63. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264744.63275.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vadivelu N, Anwar M. Buprenorphine in postoperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;28:601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding Z, Raffa RB. Identification of an additional supraspinal component to the analgesic mechanism of action of buprenorphine. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:831–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahan A, Yassen A, Romberg R, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olofsen E, et al. Buprenorphine induces ceiling in respiratory depression but not in analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:627–32. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh AP, Kaur R, Gupta R, Kumari A. Intrathecal buprenorphine versus fentanyl as adjuvant to 0.75% ropivacaine in lower limb surgeries. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32:229–33. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.182107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arora MV, Khan MZ, Choubey MS, Rasheed MA, Sarkar A. Comparison of spinal block after intrathecal clonidine-bupivacaine, buprenorphine-bupivacaine and bupivacaine alone in lower limb surgeries. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:455–61. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.177190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raffa RB, Haidery M, Huang HM, Kalladeen K, Lockstein DE, Ono H, et al. The clinical analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39:577–83. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samal S, Rani P, Chandrasekar LJ, Jena SK, Mail ID. Intrathecal buprenorphine or intrathecal dexmedetomidine for postoperative analgesia: A comparative study. Health. 2014;2:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capogna G, Celleno D, Tagariello V, Loffreda-Mancinelli C. Intrathecal buprenorphine for postoperative analgesia in the elderly patient. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:128–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb05482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celleno D, Capogna G. Spinal buprenorphine for postoperative analgesia after caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1989;33:236–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1989.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixit S. Post operative analgesia after caesarean section: An experience with intrathecal buprenorphine. Indian J Anaesth. 2007;51:515. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ipe S, Korula S, Varma S, George GM, Abraham SP, Koshy LR. A comparative study of intrathecal and epidural buprenorphine using combined spinal-epidural technique for caesarean section. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:205–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.65359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mugabure BB. Recommendations for spinal opioids clinical practice in the management of postoperative pain. J Anesthesiol Clin Sci. 2013;2:28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho B. Respiratory depression after neuraxial opioids in the obstetric setting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:956–61. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318168b443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jose DE, Ganapathi P, Anish Sharma NG, Shankaranarayana P, Aiyappa DS, Nazim M. Postoperative pain relief with epidural buprenorphine versus epidural butorphanol in laparoscopic hysterectomies: A comparative study. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:82–7. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.173612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]