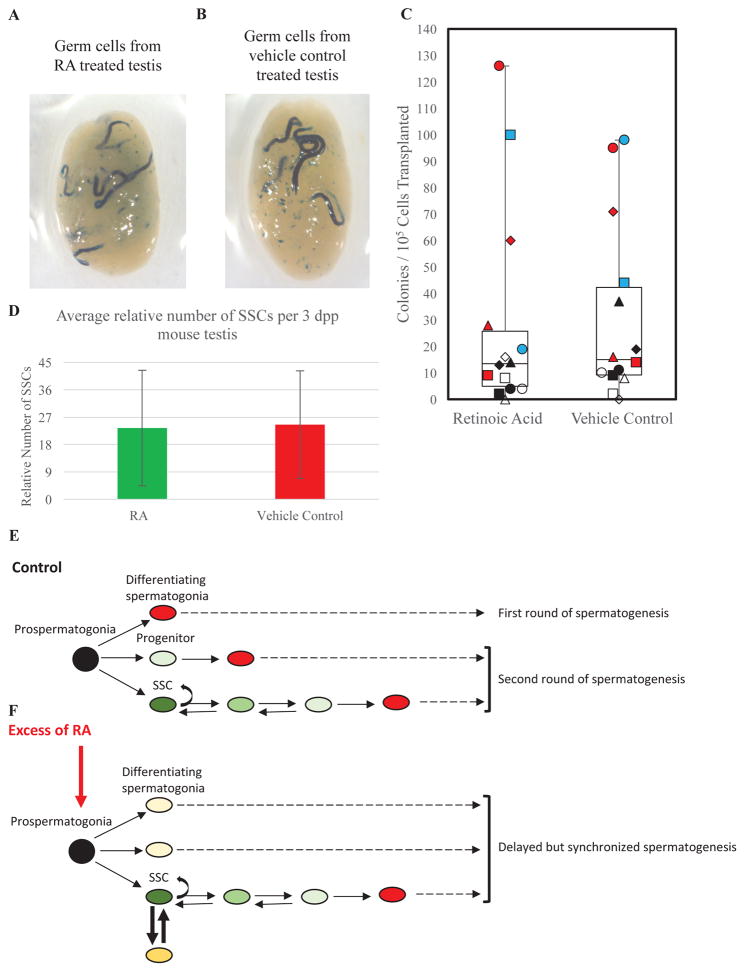

Figure 4. Excess RA exposure in the neonatal mouse testis does not alter SSC number.

Representative images of recipient testes 70 days post-transplantation that have been stained for colonies of donor-derived spermatogenesis from germ cells isolated after treatment with (A) RA or (B) vehicle control. (C) Quantitation of the number of donor-derived colonies generated by germ cell suspensions from testes of mice treated with exogenous RA or vehicle control. (D) Quantitative comparison of the number of SSCs present in testes of mice treated with exogenous RA or vehicle control. Data are mean±SEM and n=3 different cell preparations and 14 recipient mice (each individual recipient mouse is labeled differently as white, black, blue or red squares, triangles, circles, or diamonds). (E) Hypothesized model depicting the derivation of 3 distinct populations (SSCs, progenitors, and differentiating spermatogonia) from prospermatogonia in the neonatal testis. Black oval indicates prospermatogonia. Dark, medium, and light green ovals depict ID4-EGFP bright (SSCs), mid (cells transitioning from SSC to progenitor), and dim (progenitor) cells, respectively. Red ovals mark STRA8-positive differentiating spermatogonia. (F) Hypothesized model depicting the effects of excess RA exposure on ID4-EGFP + germ cell dynamics during SSC pool establishment. Black oval indicates prospermatogonia. Dark, medium, and light green ovals depict ID4-EGFP bright (SSCs), mid (cells transitioning from SSC to progenitor), and dim (progenitor) cells, respectively. Dark and light yellow ovals show ID4-EGFP and STRA8 co-positive cells. Red ovals mark STRA8-positive differentiating spermatogonia.