Summary

Each year in the United States, billions of dollars are spent combating almost half a million Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) and trying to reduce the ~29,000 patient deaths where C. difficile has an attributed role (1). In Europe, disease prevalence varies by country and level of surveillance, though yearly costs are estimated at €3 billion (2). One factor contributing to the significant healthcare burden of C. difficile is the relatively high frequency of recurrent C. difficile infections(3). Recurrent C. difficile infection (rCDI), i.e., a second episode of symptomatic CDI occurring within eight weeks of successful initial CDI treatment, occurs in ~25% of patients with 35-65% of these patients experiencing multiple episodes of recurrent disease(4, 5). Using microbial communities to treat rCDI, either as whole fecal transplants or as defined consortia of bacterial isolates have shown great success (in the case of fecal transplants) or potential promise (in the case of defined consortia of isolates). This review will briefly summarize the epidemiology and physiology of C. difficile infection, describe our current understanding of how fecal microbiota transplants treat recurrent CDI, and outline potential ways through which that knowledge can be used to rationally-design and test alternative microbe-based therapeutics.

History of C. difficile infection

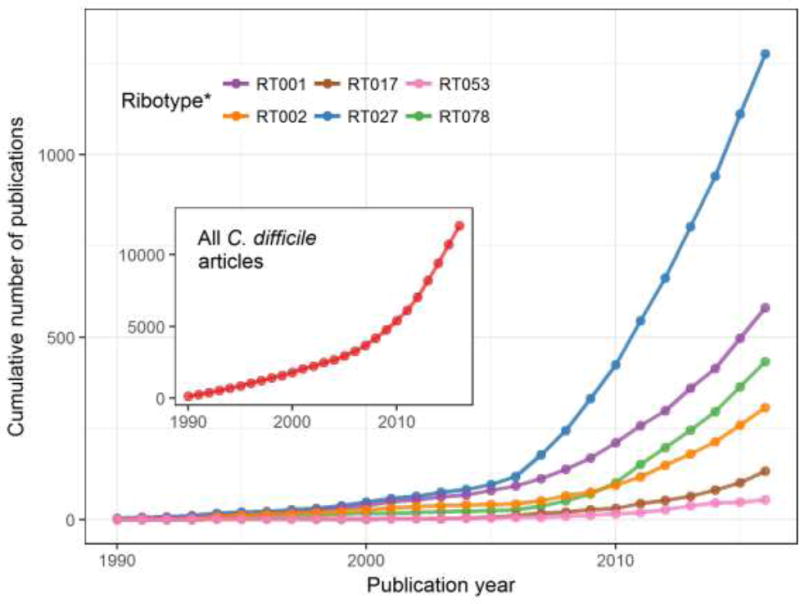

A strictly anaerobic, spore forming, Gram-positive bacillus, C. difficile (originally named Bacillus difficilis) was first identified in healthy neonates in 1935 (6). It was not until the late 1970s however, that the role of C. difficile as an etiological agent of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis was described (7-10). Throughout the 1980s and 1990s the clinical importance of C. difficile remained limited. When encountered, disease was often mild and easily controlled with antibiotics (Table 1). In the early 2000s, a new lineage of C. difficile strains (equivalently known as ribotype 027, restriction endonuclease analysis group BI, or North American pulsed-field electrophoresis 1 (NAP1)) emerged that was linked to increased disease severity, morbidity and mortality (11, 12) (Figure 1). In the following years, the ribotype 027 lineage spread throughout North America and Europe (13, 14), paralleling increases in the overall incidence and severity of C. difficile infection. Strains of the ribotype 027 lineage have often been described as “hypervirulent” (11, 15). Studies have pointed to increased toxin production (16), production of a binary toxin (17), fluoroquinolone resistance (14), increased frequency of sporulation (18), enhanced ecological fitness (19) and a higher correlation with recurrent infection (20, 21) as potential mechanisms that led to increased incidence and/or severity of infections associated with ribotype 027 strains. However, some “hypervirulent” attributes of ribotype 027 vary across strains (e.g., degree of toxin production and sporulation (22)) or are found in ribotypes not typically associated with increased disease severity (e.g., fluoroquinolone resistance (23)), making it difficult to pinpoint specific mechanisms responsible for increased incidence and/or severity of infection with ribotype 027 strains. Correspondingly, some clinical studies (24-26) failed to reproduce statistically significant increases in severe CDI in patients infected with ribotype 027 observed in other studies (13, 27, 28). Finally, even as the frequency of ribotype 027-associated CDI has stabilized or decreased in some regions (29, 30), the overall frequency of CDI has remained high, with other C. difficile ribotypes increasing in prevalence (29- 32). The picture emerging from these diverse and sometimes conflicting studies is that although the spread of the ribotype 027 lineage significantly contributed to the initial increase in CDI, factors in addition to the ribotype of the infecting strain contribute to the continued prevalence of CDI, which remains a significant threat to public health.

Table 1.

| Classification | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic carriage/colonization |

|

| Mild to moderate C. difficile infection (CDI) |

|

| Severe CDI |

|

| Severe, complicated CDI (sometimes referred to as “fulminant”) (45) |

|

| Recurrent CDI (rCDI) |

|

Figure 1. Cumulative number of C. difficile articles in PubMed.

Total article number includes all articles with ‘difficile’ in either the title or abstract; *Ribotype articles are those that have ‘difficle’ and the ribotype (or alternative nomenclature) in the title or abstract e.g. RT027 articles were classified as such if they had ‘difficile’ AND ‘Ribotype 027’ OR ‘RT027’ OR ‘Sequence Type 1’ OR ‘NAP1’ etc. Although not a definitive measure of global ribotype abundance, this data can serve as a proxy for the relative frequency of outbreaks associated with specific ribotypes.

Clostridium difficile carriage and disease

Traditionally, C. difficile infection has not been considered a risk to healthy individuals. Infection is most often preceded by disruption of the ‘healthy’ gut microbiome through antibiotic use (33). Meta-analyses examining the risk of CDI following antibiotic use found clindamycin to be the greatest hazard followed by carbapenems, fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins; more moderate risks were associated with macrolides, sulfonamides and penicillins; and no risk associated with tetracyclines (34-36). Use of proton pump inhibiters (37), inflammatory bowel disease (38), and advancing age (39) are also risk factors, likely due to changes to the gut microbiota (40, 41), and in the latter case, reduced efficacy of the immune system (39). However, increases in the rates of community-acquired C. difficile infection have also demonstrated that CDI can occur in relatively healthy populations previously thought to be at low-risk for infection, including people who had not been exposed to antibiotics within the previous 3 months (reviewed in (31, 42)), revealing that there remain additional, previously unrecognized risk factors for C. difficile infection.

Once a susceptible individual is exposed to C. difficile, multiple outcomes are possible (Table 1). Asymptomatic carriage occurs in a subset of susceptible individuals. Symptomatic C. difficile infection can manifest with increasing degrees of severity, which influences approaches used to treat disease. Following the resolution of symptomatic disease, asymptomatic shedding of spores in stool can persist for up to six weeks (43). A brief description of treatment modalities is described later in the review to provide context for the use of microbial-based therapies for treatment of C. difficile infection. However, as neither author is a clinician, we point to several recent reviews (44-46) written by clinicians experienced in diagnosis and treatment of C. difficile that provide excellent detailed descriptions of the diagnosis and treatment of CDI in adults.

Asymptomatic carriage in infants

Infants (< 1 year of age) are frequently asymptomatic carriers of C. difficile, with a wide range of carriage rates reported (2-100% (47-51)). The mechanisms that mediate high levels of asymptomatic carriage in infants are unclear, though the immature microbiome likely plays a role. During the first year of life, the infant gastrointestinal microbiome undergoes successional maturation, transitioning from a low-complexity community, dominated by facultative anaerobes and aerobic bacteria, to a complex community dominated by obligate anaerobes and more similar to the adult gastrointestinal microbiome (52, 53). Hypotheses for how infant carriage rates remain on the whole asymptomatic include the failure of the immature infant immune system to activate an inflammatory response, protective maternal antibodies transferred in breast milk, and/or the inability of toxins to interact appropriately with receptors and cause disease (reviewed in (50, 54)). Additional studies, including those that utilize physiologically relevant models of the infant gastrointestinal tract, are needed to delineate mechanisms through which infants are asymptomatically colonized with C. difficile.

Asymptomatic carriage in adults

Carriage rates decrease with increasing age (49, 50), with asymptomatic carriage rates in healthy adults reported between 0 and 15% (50, 55-57). Patients in Long-Term Care Facilities have a higher average asymptomatic carriage rate at 14.8% (95% CI 7.6% - 24.0%), though it is hard to discern if this is due to a change in the cohort physiology (microbiota, immune response), the environment, or both (58). Asymptomatic carriage is often limited in duration (reviewed in (56)) and has been associated with a lower likelihood of developing symptomatic CDI (59, 60).

Potential mechanisms underlying asymptomatic carriage

Two small studies have suggested that differences in the host microbiota could be a potential mechanism that distinguishes between asymptomatic carriage and disease (61, 62). By comparing microbial community composition between four patients with CDI, four asymptomatically colonized patients and non-colonized controls, Vincent et al (62) found that organisms classified as members of the Clostridiales incertae sedis XI family, Eubacterium species, or Clostrdium species other than C. difficile were enriched in asymptomatically colonized patients compared to patients with symptomatic CDI. By comparing eight symptomatically infected patients, eight asymptomatically colonized C. difficile patients, and healthy controls, Zhang et al (61) observed trends towards increased levels of Bacteroides, Lachnospiraceae incertae sedis, and Clostridium XIVa species and statistically significant decreases in the levels of Escherichia/Shigella species in asymptomatically colonized patients compared to healthy controls. Both asymptomatically colonized patients and patients with CDI also had significantly decreased microbial diversity compared to healthy controls. Although the authors reached different conclusions as to the potential driving forces responsible for microbiome composition differences, both studies observed increased levels of specific Clostridiales family members in asymptomatically colonized patients relative to symptomatic CDI patients and healthy controls. Although preliminary, this data suggests that expansion of these Clostridiales members may limit C. difficile pathogenesis, either by regulating levels of C. difficile and/or its toxin, or by blocking pathogenic interactions between C. difficile and the host epithelium and/or immune system.

Variation in immune response is another potential mechanism that distinguishes symptomatic from asymptomatic carriage of C. difficile. A study by Kyne et al (63) compared adults who became colonized with C. difficile upon admission to the hospital and either developed C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) or remained asymptomatic. Asymptomatic patients mounted a higher serum IgG response to Toxin A than patients who developed CDAD. This difference was only observed in patients newly exposed to C. difficile; patients in long-stay hospitalization that were either asymptomatically colonized or suffering from CDAD had similar levels of serum IgG to Toxin A (64), suggesting the timing of immune response following initial C. difficile infection may be more important than the ability to mount a serum IgG response. Furthermore, patients that mount a more robust anti-toxin immune response in the early stages of CDI are less likely to experience recurrent disease (65). This property has been exploited with the recent FDA approval of a monoclonal antibody to Toxin B, Zinplava (Bezlotoxumab), developed by Merck. In a 12-week trial, patients administered Zinplava in combination with Standard of Care antibacterial drugs (metronidazole, vancomycin or fidaxomicin) saw a 10% absolute reduction in CDI recurrence (40% relative risk reduction) compared to placebo. However, an increase (3x) in heart failure was also observed in patients with prior history of heart failure (http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ucm528793.htm). Merck have also developed an antibody to toxin A (actoxumab) but it provided no additional benefit over Zinplava.

Mechanisms governing Clostridium difficile infection and disease

C. difficile life cycle

Two physiologically distinct cell types are important in mediating C. difficile infection and disease – vegetative cells and spores. Actively growing, vegetative cells are the primary mediators of disease. In this state, C. difficile cells are capable of producing two large exotoxins, Toxin A (TcdA, 308 kDa) and Toxin B (TcdB, 270 kDa) (66). Toxins A and B are both glucosyltransferases that inactivate Rho and Ras-family GTPases within target epithelial cells; the ensuing disruption of signaling pathways causes loss of structural integrity and cell death via apoptosis (reviewed in (67, 68)). Both toxins are also capable of inducing host pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (reviewed in (69, 70). At higher concentrations, Toxin B can induce production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through induction of NADPH-oxidase complexes which leads to necrosis (71). Toxin A has also been shown to induce production of ROS (72, 73), though the mechanism of induction is unknown. A subset of C. difficile strains also produce a third toxin, binary toxin (CDT; composed of a 53 kDa enzymatic component CDTa and a 98.8 kDa binding component CDTb), which ADP-ribosylates actin leading to its depolymerization and may contribute to more severe disease (reviewed in (74)).

During C. difficile infection, a subset of vegetative cells differentiate into endospores (75, 76). Metabolically dormant, spores are intrinsically resistant to prolonged oxygen exposure, desiccation, low pH, bleach-free cleaning agents (such as ethanol hand wash commonly seen in hospitals), antibiotics and heat that would kill vegetative cells (77, 78). These characteristics make the spore the primary infectious and transmissible morphotype (79). Upon ingestion, spores pass undamaged through the low pH environment of the stomach and along the gastrointestinal tract to the lower intestine, the putative germination site (76, 80, 81). To resume active growth, spores germinate in response to multiple environmental signals.

The principal germinants of C. difficile are the primary bile salt, cholate, and its derivatives (taurocholate, deoxycholate, glycocholate), which act in combination with glycine, and potentially other amino acids (L-alanine, L-arginine, L-phenylalanine, L-cysteine, β-alanine, L-norvaline, and γ-aminobutyric acid (82)), to promote efficient germination (80, 83). Germination is competitively inhibited by a second primary bile salt, chenodeoxycholate, its derivative (lithocholate) and other analogs (84, 85).

Cholate and chenodeoxycholate are produced in the liver and conjugated to either glycine or taurine (reviewed in (86)). Following transport to the gall bladder for storage, bile salts are secreted into the duodenum to aid in digestion. The majority of bile salts are reabsorbed in the small intestine, though a portion (<10%) continues into the colon (87), where they are subject to microbiota-driven transformations (86). Bile salt hydrolases, encoded by several different members of the gastrointestinal community, cleave the taurine and glycine-conjugated primary bile salts into unconjugated bile salts (cholate and chenodeoxycholate) and free taurine or glycine (86). Enzymes for a second modification step, 7α-dehydroxylation of cholate and chenodeoxycholate to deoxycholate and lithocholate, are encoded by a limited number of bacterial species present in the colonic microbiome (86).

Potential mechanisms of colonization resistance

Patients receiving broad spectrum antibiotic treatment show marked alterations and loss of diversity in their gut microbiota (e.g.,(88, 89)). Concomitant to the loss of microbial diversity is a notable shift in bile salt composition from secondary bile salts, deoxycholate and lithocholate, to primary bile salts (90-92). Changes in the ratios of bile salts have important consequences for both germination and outgrowth of vegetative C. difficile cells. As described above, increases in the levels of cholate and taurocholate favor germination. Although increases in chenodeoxycholate could competitively inhibit germination, absorption of chenodeoxycholate by the colonic epithelium, which occurs at a rate ten times faster than cholate (93), likely reduces levels of chenodeoxycholate below that needed for inhibition (85). Both lithocholate and deoxycholate inhibit growth of vegetative C. difficile (80, 94, 95). Antibiotic treatment is known to reduce the levels of organisms that are capable of 7α-dehydroxylation (90, 95-97). Addition of Clostridium scindens, a member of the human microbiome that is capable of 7α-dehydroxylation of primary bile salts ((85), and references therein), partially restored the ability of an antibiotic-disrupted mouse microbiome to resist C. difficile infection (95).

In addition to disrupting bile salt metabolism, the large changes in microbial diversity that accompany antibiotic treatment significantly alter other features of the gastrointestinal environment that could help mediate colonization resistance. Studies in mice have demonstrated that antibiotic treatment leads to profound shifts in the levels and types of metabolites present in the cecal contents and feces (90, 98). Loss of organisms important for consumption of simple sugars and sugar alcohols liberates carbohydrates that can be metabolized by C. difficile (90, 99, 100). In mouse, hamster, and chemostat-models of C. difficile infection, competition for nutrients appears to play a role in inhibition of C. difficile growth by the microbiome (90, 99, 101, 102). Decreased microbial fermentation following antibiotic treatment also lowers the levels of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs, (90, 103)) which may provide a more favorable environment for C. difficile growth. Physiologically-relevant butyrate levels have been shown to inhibit C. difficile growth in vitro (104) and higher SCFA levels correlate with growth inhibition in porcine (105) and murine (90) models. Bacteriocins targeting Gram-positive organisms, including C. difficile (e.g., nisin, lacticin 3147 (106, 107)), or narrowly targeting C. difficile (thuricin CD (108)) are another potential mechanism for preventing C. difficile colonization that could be encoded by antibiotic-susceptible members of the microbiome. Finally, the commensal microbiome plays a significant role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis, promoting barrier integrity, and educating the immune system (109, 110). Immune responses to C. difficile infection can play a role in limiting C. difficile disease (e.g., IL-25 mediated recruitment of eosinophils) or causing more severe disease outcomes (e.g., IL-23 mediated neutrophil recruitment and histopathology (111, 112)) and may also differentiate patients who develop C. difficile disease from asymptomatic carriers (reviewed in (70, 113)).

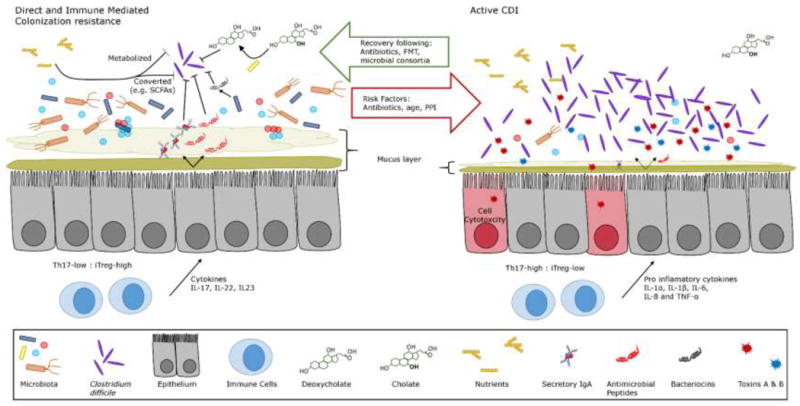

In summary, disruption of the gut microbiota by use of broad spectrum antibiotics causes dramatic changes that inhibit the ability of the host to resist colonization by C. difficile. Antibiotic treatment alters the bile salt composition in the intestinal lumen, leading to conditions that promote spore germination. Decreases in secondary bile salts, as well as the presence of fermentable carbohydrates and absence of potentially inhibitory molecules produced by the microbiome, provide a niche in which C. difficile can replicate and cause disease. Disrupted interactions between the microbiome, the host epithelium, and host immune system due to dysbiosis inhibit other host-encoded mechanisms to limit C. difficile infection and disease. In cases of recurrent CDI, it appears that colonization resistance cannot be restored without further intervention (Figure 2). One approach that has shown significant success in restoring colonization resistance and ameliorating CDI is Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT). Better understanding how FMT ameliorates disease should provide insights into the rational design of defined communities for treatment of recurrent CDI.

Figure 2.

Under normal circumstances the gastrointestinal tract is able to resist infection by Clostridium difficle. This is thought to be acomplished by a combination of factors mediated by the host and colonization resistance due to the indigenous microbiota. These mechanisms, expanded upon in the main text, include: 1)competition for nutrients and their conversion into metabolites inhibitory to C. difficile, 2)microbial conversion of primary to secondary bile salts such as deoxycholate which can induce germination of C. difficile spores but prevent the growth of vegetative C. difficile, 3)production of antimicrobial peptides and bacteriocins by the host microbiota, and 4)a balanced host immune response that includes production of immunoglobulins, accumulation of protective iTreg cells in the lamina propria, and release of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Upon disruption of these resistance mechanisms, primarily through antibiotic use, there is an accumulation of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells and reduction in bacterial diversity. In this state C. difficile is able to invade and proliferate, causing toxin mediated damage to the epithlium. In many cases following suitable antibiotic treatment for CDI the indiginous microbiota is able to recover and reestablish colonization resistance. However, in a significant number of cases this does not occur and patients are liable to suffer relapse. FMT has been shown to be remarkably successful for treating these patients, likely because multiple facets of colonization resistance are restored.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

The historical treatment for primary, non-severe, CDI involves oral administration (over 10- 14-days) of either metronidazole or vancomycin (45). In most cases, this is sufficient for full resolution of disease. For ~25% of patients, however, at least 1 recurrence of disease is observed and of those patients up to 35-65% will suffer multiple episodes, developing chronic, recurrent disease (rCDI) (5, 114). Relapses can be caused by the initial infective strain or by reinfection from another C. difficile strain acquired from the environment (115-119). Administering a tapering or pulsed course of vancomycin can reduce rCDI occurrences (120), presumably by killing off vegetative cells as they germinate from the spore form. Recently, the narrow spectrum antibiotic fidaxomicin has been approved for CDI treatment. Fidaxomicin is non-inferior to vancomycin for CDI treatment and results in fewer relapses of disease (121). Whereas a course of metronidazole or vancomycin can be relatively inexpensive ($35 - $700 respectively), fidaxomicin can cost $3,360 for a 10 day course (122). This has led to some reluctance to prescribe fidaxomicin, however, it has been argued that compared to the expense (financial and to the health of the patient) associated with rCDI, fidaxomicin is the superior first line treatment option (123). Despite the increased efficacy of fidaxomicin, >10% of patients will develop recalcitrant rCDI (124).

Because of the limited options available for pharmaceutical treatment of rCDI, interest has increased in alternative treatments. FMT is one therapy that has risen in prominence since the early 2010s, due primarily to its startlingly high efficacy (over 90% success rate reported in some studies (125, 126)). FMT, however, is not a new idea. The earliest known roots can be traced back to the consumption of “yellow soup” in 4th century China by patients suffering with food poisoning or severe diarrhea (127) and FMT has been utilized by veterinarians since the 1600s when it was described by Italian anatomist, Fabricius Aquapendente, for treating ruminants (114). The first reported use of FMT in humans as a treatment for pseudomembranous colitis (potentially caused by C. difficile) occurred in 1958 (128) and its first definitive use against CDI was reported in the early 1980s (129).

Over the past five years, several controlled trials have been reported that evaluate the efficacy of FMT and explore how different variables impact outcome. We summarize some of the key outcomes of these studies below and discuss key variables (FMT donors, FMT recipients, and mode of administrations) with their potential to influence efficacy. These data are presented to provide context for discussion of therapeutic microbes and not intended as guidelines for treatment. More comprehensive evaluations of FMT, including guides for clinicians on how to implement FMT, have been recently published (130, 131).

Key variables with potential to influence success of FMT

FMT Donors

The goal of FMT is to cure patients with recalcitrant rCDI by reintroducing a diverse microbiome within the colon, restoring a state of colonization resistance. There is, however, inherent risk in the transfer of biological material between donor and patient. Because of the potential to transmit infectious agents, donor stool samples are often screened for C. difficile toxin, enteric bacterial pathogens, parasites, and rotavirus; whilst blood samples from potential donors are screened for hepatitis A, B, and C as well as HIV and syphilis; however, the regulatory requirements governing these tests vary (reviewed in (132, 133).

The role of the gastrointestinal microbiome has been increasingly studied in recent years, highlighting potential complications with wholesale transfer of microbial communities between individuals. Studies have linked the gut microbiome in numerous conditions including (but not limited to): depression (134) inflammatory bowel disease (135), and metabolic syndrome (136). An obese phenotype has been shown to be transmissible in animal studies (137) and at least one case study infers this can also take place in humans (138).

Donors can be split into two main groups: Universal and patient selected. Universal donors enable expedited treatment by providing a bank of processed fecal material that has already undergone a rigorous screening process (e.g., (139, 140). This option requires pre-planning and protocols to be in place within the medical establishment (discussed in (141)), and has recently been standardized by Rebiotix in their formulation RBX2660 (142) which is currently advancing to Phase 3 clinical development following successful treatment in Phase 2B trials (78.8% treatment). Patient-selected donors are usually family members or close friends (e.g., (139)). There is also the potential for patients to acquire untested stool from friends or family and to self-administer using one of the methods easily obtainable online (e.g., http://thepowerofpoop.com/epatients/fecal-transplant-instructions/). This practice is unadvisable and considered especially risky. Even with well screened samples there is the possibility of low amounts of highly contagious infectious agents to slip through undetected (143).

FMT recipients

Patient criteria for FMT typically requires symptomatic, toxin-positive C. difficile disease that has recurred at least once following cessation of antibiotic treatment (125, 139, 140, 144, 145). Reports suggest that FMT can be both safe and effective in severely ill patients (Table 2), though further clinical enquiry is required. Contraindications for use of FMT differ by hospital though can often include: age <18 years, medical frailty (life expectancy from non-CDI disease <1 yr), prolonged compromised immunity because of recent chemotherapy, the presence of HIV infection with CD4 count of less than 240, neutropenia (<0.5 × 109/L), peripheral WBC (>30 × 109/L), toxic megacolon, pregnancy, and corticosteroid use (125, 139, 144). A more complete understanding of patient populations most likely to benefit from FMT is continuing to develop as new studies are completed. The fact that some groups have reported successful FMT to children (146) and patients with severe disease (Table 2), criteria used by other groups as contraindications to treatment, indicate that these treatment considerations are continuing to evolve and outlines the need for increased controlled trials.

Table 2.

Results of FMT in severely ill patients

| Complication/extenuating factors | Success rate | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Severe CDI: Hypoalbuminemia (<3 g/dL) with peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count >15,000/μl and/or abdominal tenderness. | 91% (Primary cure rate) | (145) |

| Complicated CDI: Occurrence of 1 or more of the following as a consequence of CDI: admission to the intensive care unit, altered mental status, hypotension, fever >38.5°C, ileus, WBC <2000 or >30,000/μl, lactate >2.2 mmol/L, or evidence of end-organ damage. | 66% (Primary cure rate) | (145) |

| Fulminant, life-threatening CDI | case report | (175) |

| Fulminant CDI in an allogeneic stem cell transplant patient | case report | (176) |

| Fulminant, life-threatening CDI with Toxic megacolon | case report | (177) |

Route of Administration

The majority of reported FMT procedures have been performed with fresh stool suspensions, though there appears to be no significant differences in infection clearance for fresh versus frozen samples (144). FMT for rCDI has been reported successful whether administered via a top-down nasogastric (147) or capsule (140) route; or bottom-up colonoscopy (148) or enema (149); though a slight increase in efficacy has been observed with lower GI delivery (See Table 3) (150, 151). Self-administered enemas can also be highly efficacious (152) and may be preferred by some patients as they can be performed at home (ideally in consultation with a medical professional and with a sample that has been screened for infectious agents). Adverse effects associated with FMT route of delivery (reviewed in (153); summarized in Table 3) should be taken into account along with success rates. One problem, regardless of administration route, is the potential for injury caused by endoscopic tools. Encapsulated FMT (shown to be successful in limited studies) may therefore be an attractive option, although use is limited in patients susceptible to esophageal reflux (140).

Table 3.

Comparison of rates of success and adverse events as a function of route of delivery for FMT

| Delivery | Success rate* | Adverse Events† | Serious Adverse Events†† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper GI | 83.5% | 43.6% | 2.0% |

| Lower GI | 85.1% | 17.7% | 6.1% |

Success rate indicates 90-day cure rate of rCDI based upon multi study data in Furuya-Kanamori L et al (151).

Adverse events include any unfavorable and unintended sign (including an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom, or disease temporally associated with FMT.

Serious Adverse Events include: death, life-threatening experience, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability or incapacity, congenital anomaly or birth defect, or an important medical event (178). Adverse event data includes multiple, rCDI & non-rCDI related, FMT studies.

Recolonization of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) after FMT

Human stool is a complex mixture of Bacteria, Archaea, human colonocytes, Fungi, Protists, viruses (human, bacterial, and archaeal), metabolites, antibodies, and other proteins (reviewed in (154)). The Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the dominant phyla in healthy individuals (though this is not the case for some traditional hunter gathers (155)), yet their ratios differ between people (156). Despite microbial community variation, metabolic pathways present within the microbial gene pool remain evenly distributed across healthy individuals (157). Patients with rCDI, in contrast, have a markedly reduced microbial diversity that differs significantly from healthy samples (158). At the phylum level, the microbiota of rCDI patients is dominated by Proteobacteria with an abundance of Enterobacteriaceae often observed (159-161). Following FMT, there is an immediate shift in the patient gut microbiota to look more like the donor. Post-transplant samples are enriched for Bacteroidetes whilst the overall abundance of Proteobacteria is significantly reduced. This suppression of Proteobacteria populations may play an important role in resetting intestinal immune homeostasis, as several species of Proteobacteria are capable of thriving in the inflamed intestine and perpetuating continued inflammation (reviewed in (162)) The stability and similarity of recipients’ microbiota following transplant when compared to donor can vary, suggesting that some microbiota compositions may be more stable (160). In a recent study utilizing shotgun metagenomic sequencing to examine microbial colonization following FMT, Lee et al (163) observed a significant increase in Bacteroidetes post-transplant and, interestingly, a negative correlation between genes involved in sporulation and successful colonization of the FMT recipient. This suggests that alternative treatments that rely heavily or solely on spore forming bacteria (such as Seres Therapeutics SER-109, described in detail below) may suffer from limited colonization efficiency.

Alternatives to FMT

Despite its efficacy, the mechanisms that underlie successful FMT are not well understood. FMT mediates restoration of a diverse microbial population within recipients, but it is not clear whether the curative effect of FMT is due solely to the bacteria present. Although very few serious adverse events have been reported following FMT (noted above and Table 3), it is unclear what long-term impacts fecal microbiota transplantation may have upon the recipient. For these reasons, several alternative microbiota-driven approaches are being investigated.

Tvede and Rask-Madsen described the use of a defined consortia of 10 bacterial isolates to treat rCDI in 5 patients (164). They observed 100% efficacy with loss of C. difficile and its toxin and no recurrence during the 1 yr follow-up period. The authors proposed mechanism, based upon in vitro antagonism studies and stool cultures before and after treatment, was that Blautia productus, Escherichia coli and Clostridium bifermentans present in the consortia could directly antagonize C. difficile, which itself was actively inhibiting the survival of Bacteroides strains. In the absence of C. difficile, the levels of Bacteroides increased which may be important for maintenance of colonization resistance. Follow up studies from this group have not been reported, although a consortia based upon their work is being evaluated in an ongoing clinical trial (NCT01868373).

In 2013, Elaine Petrof and her colleagues reported the successful use of a consortia of 33 human fecal isolates to treat two patients with rCDI (165). They analyzed the change in microbiome composition before and after treatment by Ion Torrent sequencing of the V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene and observed that 50-70% of sequence reads were identical to the 16S genes present in the organisms in their consortia in the first two weeks following treatment. Although the persistence of sequences identical to the treatment consortia declined over time (both patients were treated with antibiotics for other conditions), neither patient experienced a disease recurrence. Follow-up studies using mouse model of C. difficile colitis, indicated that their synthetic consortia, now named MET-1, limits CDI by inhibiting toxigenicity of TcdA (166). Somewhat surprisingly, MET-1 had no impact on levels of C. difficile in the mouse model. A larger human clinical trial (NCT01372943) is ongoing and will provide additional insights into the efficacy of MET-1 when tested against a larger patient population.

Seres Therapeutics has developed preparations of Firmicutes spores isolated from human fecal donors (SER-109) to treat rCDI. These preparations, which vary from donor to donor, are composed of 50 ± 8 distinct operational taxonomic units (≥97% identity) based upon Illumina sequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA genes (167). Results from Phase II clinical trials, demonstrated a 96.7% success rate at eight weeks post treatment (no CDI in 29 of 30 patients), although three successfully-treated patients had recurrence of CDI (one following antibiotic treatment) in the 8-24 week follow-up period (167). Microbial community analyses of patient samples before and after treatment demonstrated significant changes. In addition to an overall increase in microbial diversity and the expected increases in the proportion of Firmicutes (present in the SER-109 consortia), the authors observed increases in the proportion of Bacteroidetes sequences and decreases in the number of Klebsiella sequences in treated patients. Interesting parallels can be drawn with the work of Tvede and Rask-Madsen who proposed that suppression of C. difficile by two species in the Firmicutes phylum (Blautia producta and Clostridium bifermentans) allowed re-emergence of Bacteroides species which were being suppressed by C. difficile. The 89-subject Phase II trial of SER-109, however, did not show a reduced relative risk of recurrence of CDI. Subsequent re-analysis of the data by Seres Health suggests there may have been false positive CDI diagnosis of patients at time of enrollment and potentially during putative relapse due to Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT) based testing without ensuing cytotoxin assays. In these cases, positive result indicates that C. difficile cytotoxin genes are present, but not necessarily that C. difficile is the source of clinical symptoms. (Although there is some support for diagnosis based solely upon a positive NAAT in the presence of symptoms, other experts recommend use of a multi-step approach to distinguish asymptomatic from symptomatic colonization (reviewed in (45)). The analysis also suggested that the 1 × 108 spores received by patients in the Phase II trial (Phase I recipients received doses from 3 × 107 to 2 × 109 spores) may have been suboptimal – possibly due to the limited colonization efficiency of spore forming bacteria (163). Despite the setback, Seres Health recently announced (June 12, 2017) the initiation of a Phase 3 SER-109 clinical study (ECOSPOR III) in patients with multiply recurrent C. difficile infection. This study will aim to enroll 320 patients and utilize a cytotoxin assay to diagnose C. difficile rather than PCR as well as an increased treatment dose.

In 2014 as a follow-up to a smaller 2009 study, Johan Bakken reported on the combined use of probiotic kefir with tapered reduction in vancomycin or metronidazole as an alternative treatment for rCDI (168, 169). In Bakken’s study, a commercially available preparation of kefir produced by Lifeway (11 bacterial and 1 yeast species) was self-administered by patients three times per day for 6 weeks during staggered vancomycin/metronidazole withdrawal. Kefir self-administration continued for 2 months following the end of antibiotics. All 25 patients were free of symptoms at the end of the staggered antibiotic withdrawal and 21 of 25 patients remained asymptomatic for 9 months following the end of the study. Despite no reported adverse effects in CDI patients in either study, the same probiotic kefir when used in a mouse model of CDI was found to exacerbate disease, highlighting the difficulty in studying translational therapies in animal models (170).

Gerding and colleagues have also evaluated the ability of non-toxigenic C. difficile administration to prevent and/or resolve rCDI (171). In their study, patients who had a primary episode of CDI or a single recurrence of CDI were recruited and treated with preparations of non-toxigenic spores for 7-14 days (based upon treatment group). Recurrence rate in patients receiving non-toxigenic C. difficile spores was 11% compared to 30% for placebo-treated patients. Treatment with non-toxigenic C. difficile holds promise, and success may be improved by changes in administration or by coupling with other microbe based therapeutics to more fully restore colonization resistance. One concern with this approach, however, is the ability of non-toxigenic strains to acquire the pathogenicity locus (PathLoc) encoding toxins A & B from pathogenic strains via horizontal gene transfer (172).

Many microbially-based treatments for C. difficile target rCDI but there is also an opportunity for these treatments to be used for C. difficile prophylaxis. A number of commercially available probiotic preparations have been used for C. difficile prophylaxis in several different institutions, with reported decreases in the overall rate of CDI (reviewed in (173)), although there is still not sufficient consensus to recommend widespread use of probiotics in CDI prophylaxis (reviewed in (174)) .

Conclusions

An intact gut microbiome exerts wide ranging influence on both the host and its constituent members. Complex carbohydrates are fermented to produce SCFAs that can both inhibit certain bacterial species and provide energy to the cells that line the intestine; epithelial barrier integrity is promoted; bile salts are modified; and a milieu of communication signals and bacteriocins are produced. These factors, and others, result in a state of colonization resistance that prevents CDI. Upon significant disruption, some, or all, of these factors are lost leaving the host susceptible to C. difficile infection. For most patients, antibiotic treatment is sufficient to cure CDI and the gut microbiome eventually returns to a state of restored functionality and colonization resistance. However, for a significant minority the microbiota fails to recover and recurrent disease occurs. For these patients, the transfer of an exogenous source of microbes via FMT has proved to be extremely efficacious. The discovery and application of specific consortia of microbes that can be administered in a drug like fashion has proven to be more elusive but by targeting those microbes that can recapitulate the microbiome functionality there is great promise for the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Vince Young (University of Michigan) for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by seed funding from Baylor College of Medicine and by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Grants AI121522 and AI234290 to Robert Britton.

References

- 1.Lessa FC, Winston LG, McDonald LC. Emerging Infections Program C. difficile Surveillance Team, Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2369–2370. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1505190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AM, Kuijper EJ, Wilcox MH. Clostridium difficile: a European perspective. J Infect. 2013;66:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah DN, et al. Economic burden of primary compared with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized patients: a prospective cohort study. J Hosp Infect. 2016;93:286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borody TJ, et al. Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:475–83. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000128988.13808.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: A review of risk factors, treatments, and outcomes. J Infect. 2009;58:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall IC, O’Toole E. Intestinal flora in newborn infants: with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficilis. Am J Dis Child. 1935;49:390–402. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartlett JG, Onderdonk AB, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. Clindamycin-associated colitis due to a toxin-producing species of Clostridium in hamsters. J Infect Dis. 1977;136:701–705. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George RH, et al. Identification of Clostridium difficile as a cause of pseudomembranous colitis. Br Med J. 1978;1:695. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6114.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George WL, Sutter VL, Goldstein EJ, Ludwig SL, Finegold SM. Aetiology of antimicrobial-agent-associated colitis. Lancet (London, England) 1978;1:802–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)93001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson HE, Price AB, Honour P, Borriello SP. Clostridium difficile and the aetiology of pseudomembranous colitis. Lancet (London, England) 1978;1:1063–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pepin J, Valiquette L, Cossette B. Mortality attributable to nosocomial Clostridium difficile-associated disease during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain in Quebec. CMAJ. 2005;173:1037–1042. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loo VG, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–2449. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald LC, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He M, et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile. Nat Genet. 2012;45:109–113. doi: 10.1038/ng.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghose C. Clostridium difficile infection in the twenty-first century. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e62. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warny M, et al. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet. 2005;366:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowardin CA, et al. The binary toxin CDT enhances Clostridium difficile virulence by suppressing protective colonic eosinophilia. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16108. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrigan M, et al. Human hypervirulent Clostridium difficile strains exhibit increased sporulation as well as robust toxin production. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:4904–4911. doi: 10.1128/JB.00445-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson CD, Auchtung JM, Collins J, Britton RA. Epidemic Clostridium difficile strains demonstrate increased competitive fitness compared to nonepidemic isolates. Infect Immun. 2014;82:2815–2825. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01524-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsh JW, et al. Association of Relapse of Clostridium difficile Disease with BI/NAP1/027. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:4078–4082. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02291-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson C, Kim P, Lee C, Bersenas A, Weese JS. Comparison of Clostridium difficile isolates from individuals with recurrent and single episode of infection. Anaerobe. 2015;33:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson PE, et al. The relationship between phenotype, ribotype, and clinical disease in human Clostridium difficile isolates. Anaerobe. 2013;24:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spigaglia P, et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Clostridium difficile isolates from a prospective study of C. difficile infections in Europe. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:784–789. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirard S, Valiquette L, Fortier LC. Lack of Association between Clinical Outcome of Clostridium difficile Infections, Strain Type, and Virulence-Associated Phenotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4040–4046. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walk ST, et al. Clostridium difficile ribotype does not predict severe infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cid/cis786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aitken SL, et al. In the Endemic Setting, Clostridium difficile Ribotype 027 Is Virulent But Not Hypervirulent. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1318–1323. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker AS, et al. Relationship between bacterial strain type, host biomarkers, and mortality in Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1589–600. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao K, et al. Clostridium difficile Ribotype 027: Relationship to Age, Detectability of Toxins A or B in Stool With Rapid Testing, Severe Infection, and Mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:233–241. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilcox MH, et al. Changing Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile Infection Following the Introduction of a National Ribotyping-Based Surveillance Scheme in England. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1056–1063. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jassem AN, et al. Characterization of Clostridium difficile Strains in British Columbia, Canada: A Shift from NAP1 Majority (2008) to Novel Strain Types 2013 in One Region. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/8207418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DePestel DD, Aronoff DM. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile Infection. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26:464–475. doi: 10.1177/0897190013499521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waslawski S, et al. Clostridium difficile ribotype diversity at six healthcare institutions in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00056-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slimings C, Riley TV. Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: update of systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:881–891. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown KA, Khanafer N, Daneman N, Fisman DN. Meta-analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2326–2332. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02176-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deshpande A, et al. Community-associated clostridium difficile infection antibiotics: A meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1951–1961. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vardakas KZ, Trigkidis KK, Boukouvala E, Falagas ME. Clostridium difficile infection following systemic antibiotic administration in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janarthanan S, Ditah I, Adler DG, Ehrinpreis MN. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and proton pump inhibitor therapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1001–1010. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao K, Higgins PDR. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Clostridium difficile Infection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1744–1754. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin JH, High KP, Warren CA. Older Is Not Wiser, Immunologically Speaking: Effect of Aging on Host Response to Clostridium difficile Infections. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:916–922. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Claesson MJ, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seto CT, Jeraldo P, Orenstein R, Chia N, DiBaise JK. Prolonged use of a proton pump inhibitor reduces microbial diversity: implications for Clostridium difficile susceptibility. Microbiome. 2014;2:42. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bloomfield LE, Riley TV. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Community- Associated Clostridium difficile Infection: A Narrative Review. Infect Dis Ther. 2016:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0117-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sethi AK, Al-Nassir WN, Nerandzic MM, Bobulsky GS, Donskey CJ. Persistence of Skin Contamination and Environmental Shedding of Clostridium difficile during and after Treatment of C. difficile Infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;31:21–27. doi: 10.1086/649016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen SH, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–55. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bagdasarian N, Rao K, Malani PN. Diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:398–408. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fehér C, Mensa J. A Comparison of Current Guidelines of Five International Societies on Clostridium difficile Infection Management. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5:207–230. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0122-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larson HE, Barclay FE, Honour P, Hill ID. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile in infants. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:727–733. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collignon A, et al. Heterogeneity of Clostridium difficile isolates from infants. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:319–322. doi: 10.1007/BF01956743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuki S, et al. Colonization by Clostridium difficile of neonates in a hospital, and infants and children in three day-care facilities of Kanazawa, Japan. Int Microbiol. 2005;8:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jangi S, Lamont JT. Asymptomatic colonization by Clostridium difficile in infants: implications for disease in later life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:2–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d29767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rousseau C, et al. Clostridium difficile carriage in healthy infants in the community: a potential reservoir for pathogenic strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1209–1215. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koenig JE, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl):4578–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bäckhed F, et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:852. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McFarland LV, Brandmarker SA, Guandalini S. Pediatric Clostridium difficile: a phantom menace or clinical reality? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:220–231. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kato H, et al. Colonisation and transmission of Clostridium difficile in healthy individuals examined by PCR ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:720–727. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-8-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furuya-Kanamori L, et al. Asymptomatic Clostridium difficile colonization: epidemiology and clinical implications. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:516. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1258-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian TT, et al. Molecular Characterization of Clostridium difficile Isolates from Human Subjects and the Environment. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziakas PD, et al. Asymptomatic Carriers of Toxigenic C. difficile in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence and Risk Factors. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117195–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samore MH, et al. Clostridium difficile colonization and diarrhea at a tertiary care hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:181–187. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shim JK, Johnson S, Samore MH, Bliss DZ, Gerding DN. Primary symptomless colonisation by Clostridium difficile and decreased risk of subsequent diarrhoea. Lancet. 1998;351:633–636. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang L, et al. Insight into alteration of gut microbiota in Clostridium difficile infection and asymptomatic C. difficile colonization. Anaerobe. 2015;34:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vincent C, et al. Bloom and bust: intestinal microbiota dynamics in response to hospital exposures and Clostridium difficile colonization or infection. Microbiome. 2016;4:12. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:390–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanchez-Hurtado K, et al. Systemic antibody response to Clostridium difficile in colonized patients with and without symptoms and matched controls. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:717–724. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47713-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Solomon K. The host immune response to Clostridium difficile infection. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2013;1:19–35. doi: 10.1177/2049936112472173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin-Verstraete I, Peltier J, Dupuy B. The Regulatory Networks That Control Clostridium difficile Toxin Synthesis. Toxins (Basel) 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/toxins8050153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pruitt RN, Lacy DB. Toward a structural understanding of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:28. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jank T, Belyi Y, Aktories K. Bacterial glycosyltransferase toxins. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:1752–1765. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Janoir C. Virulence factors of Clostridium difficile and their role during infection. Anaerobe. 2016;37:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Péchiné S, Collignon A. Immune responses induced by Clostridium difficile. Anaerobe. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Farrow MA, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin B-induced necrosis is mediated by the host epithelial cell NADPH oxidase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18674–18679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313658110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qiu B, Pothoulakis C, Castagliuolo I, Nikulasson S, LaMont JT. Participation of reactive oxygen metabolites in Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced enteritis in rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G485–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.2.G485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim H, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin A regulates inducible cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2 synthesis in colonocytes via reactive oxygen species and activation of p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21237–21245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gerding DN, Johnson S, Rupnik M, Aktories K. Clostridium difficile binary toxin CDT: mechanism, epidemiology, and potential clinical importance. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:15–27. doi: 10.4161/gmic.26854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janoir C, et al. Adaptive strategies and pathogenesis of clostridium difficile from In vivo transcriptomics. Infect Immun. 2013;81 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00515-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koenigsknecht MJ, et al. Dynamics and establishment of Clostridium difficile infection in the murine gastrointestinal tract. Infect Immun. 2015;83:934–941. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02768-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jump RLP, Pultz MJ, Donskey CJ. Vegetative Clostridium difficile survives in room air on moist surfaces and in gastric contents with reduced acidity: a potential mechanism to explain the association between proton pump inhibitors and C. difficile-associated diarrhea? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2883–2887. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01443-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carroll KC, Bartlett JG. Biology of Clostridium difficile: implications for epidemiology and diagnosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:501–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deakin LJ, et al. The Clostridium difficile spo0A gene is a persistence and transmission factor. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2704–2711. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00147-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL. Bile salts and glycine as cogerminants for Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2505–2512. doi: 10.1128/JB.01765-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Theriot CM, Bowman AA, Young VB. Antibiotic-Induced Alterations of the Gut Microbiota Alter Secondary Bile Acid Production and Allow for Clostridium difficile Spore Germination and Outgrowth in the Large Intestine. mSphere. 2016;1:e00045–15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00045-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Howerton A, Ramirez N, Abel-Santos E. Mapping interactions between germinants and Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:274–282. doi: 10.1128/JB.00980-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bhattacharjee D, et al. Reexamining the Germination Phenotypes of Several Clostridium difficile Strains Suggests Another Role for the CspC Germinant Receptor. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:777–786. doi: 10.1128/JB.00908-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL. Chenodeoxycholate Is an Inhibitor of Clostridium difficile Spore Germination. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1115–1117. doi: 10.1128/JB.01260-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL. Inhibiting the Initiation of Clostridium difficile Spore Germination using Analogs of Chenodeoxycholic Acid, a Bile Acid. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:4983–4990. doi: 10.1128/JB.00610-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ridlon JM. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res. 2005;47:241–259. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500013-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dawson PA, Lan T, Rao A. Bile acid transporters. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2340–2357. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900012-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Young VB, Schmidt TM. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea accompanied by large-scale alterations in the composition of the fecal microbiota. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1203–1206. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1203-1206.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Theriot CM, et al. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3114. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang Y, Limaye PB, Renaud HJ, Klaassen CD. Effect of various antibiotics on modulation of intestinal microbiota and bile acid profile in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;277:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Allegretti JR, et al. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection associates with distinct bile acid and microbiome profiles. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1142–53. doi: 10.1111/apt.13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mekhjian HS, Phillips SF, Hofmann AF. Colonic absorption of unconjugated bile acids: perfusion studies in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24:545–550. doi: 10.1007/BF01489324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wilson KH. Efficiency of various bile salt preparations for stimulation of Clostridium difficile spore germination. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1017–1019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.4.1017-1019.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Buffie CG, et al. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2014;517:205–208. doi: 10.1038/nature13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Samuel P, Holtzman CM, Meilman E, Sekowski I. Effect of neomycin and other antibiotics on serum cholesterol levels and on 7alpha-dehydroxylation of bile acids by the fecal bacterial flora in man. Circ Res. 1973;33:393–402. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giel JL, Sorg Ja, Sonenshein AL, Zhu J. Metabolism of bile salts in mice influences spore germination in Clostridium difficile. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Antunes LCM, et al. Effect of antibiotic treatment on the intestinal metabolome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1494–1503. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01664-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilson KH, Perini F. Role of competition for nutrients in suppression of Clostridium difficile by the colonic microflora. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2610–2614. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2610-2614.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scaria J, et al. Comparative nutritional and chemical phenome of Clostridium difficile isolates determined using phenotype microarrays. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;27:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ng KM, et al. Microbiota-liberated host sugars facilitate post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens. Nature. 2013;502:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nagaro KJ, et al. Nontoxigenic Clostridium difficile protects hamsters against challenge with historic and epidemic strains of toxigenic BI/NAP1/027 C. difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5266–5270. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00580-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Høverstad T, et al. Influence of ampicillin, clindamycin, and metronidazole on faecal excretion of short-chain fatty acids in healthy subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986;21:621–626. doi: 10.3109/00365528609003109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rolfe RD. Role of volatile fatty acids in colonization resistance to Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1984;45:185–191. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.185-191.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.May T, Mackie RI, Fahey GC, Cremin JC, Garleb KA. Effect of fiber source on short-chain fatty acid production and on the growth and toxin production by Clostridium difficile. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:916–922. doi: 10.3109/00365529409094863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rea MC, et al. Effect of broad-and narrow-spectrum antimicrobials on Clostridium difficile and microbial diversity in a model of the distal colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:4639–4644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001224107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mathur H, Rea MC, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. The potential for emerging therapeutic options for Clostridium difficile infection. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:696–710. doi: 10.4161/19490976.2014.983768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rea MC, et al. Thuricin CD, a posttranslationally modified bacteriocin with a narrow spectrum of activity against Clostridium difficile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9352–9357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913554107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hasegawa M, et al. Protective role of commensals against Clostridium difficile infection via an IL-1β-mediated positive-feedback loop. J Immunol. 2012;189:3085–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions Between the Microbiota and the Immune System. Science (80- ) 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Buonomo EL, et al. Role of interleukin 23 signaling in Clostridium difficile colitis. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:917–920. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McDermott AJ, et al. Interleukin-23 (IL-23), independent of IL-17 and IL-22, drives neutrophil recruitment and innate inflammation during Clostridium difficile colitis in mice. Immunology. 2016;147:114–124. doi: 10.1111/imm.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bibbò S, et al. Role of microbiota and innate immunity in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:462740. doi: 10.1155/2014/462740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Borody TJ, et al. Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:475–483. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000128988.13808.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wilcox MH, Fawley WN, Settle CD, Davidson A. Recurrence of symptoms in Clostridium difficile infection--relapse or reinfection? J Hosp Infect. 1998;38:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Barbut F, et al. Epidemiology of recurrences or reinfections of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2386–2388. doi: 10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t031141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tang-Feldman Y, Mayo S, Silva J, Jr, Cohen SH. Molecular analysis of Clostridium difficile strains isolated from 18 cases of recurrent clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3413–3414. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3413-3414.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kamboj M, et al. Relapse versus reinfection: surveillance of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1003–1006. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Figueroa I, et al. Relapse versus reinfection: recurrent Clostridium difficile infection following treatment with fidaxomicin or vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 2):S104–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Surawicz CM. Breaking the cycle: treatment strategies for 163 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1769–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Louie TJ, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422–431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dhiren P, Goldman-Levine JD. Fidaxomicin (Dificid) for Clostridium difficile infection. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2011;53:73–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Watt M, McCrea C, Johal S, Posnett J, Nazir J. A cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis of first-line fidaxomicin for patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in Germany. Infection. 2016;44:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0894-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Louie TJ, et al. Fidaxomicin preserves the intestinal microbiome during and after treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and reduces both toxin reexpression and recurrence of CDI. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 2):S132–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.van Nood E, et al. Duodenal Infusion of Donor Feces for Recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sofi AA, et al. Relationship of symptom duration and fecal bacteriotherapy in Clostridium difficile infection-pooled data analysis and a systematic review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:266–273. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.743585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang F, Luo W, Shi Y, Fan Z, Ji G. Should we standardize the 1,700-year-old fecal microbiota transplantation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1755–1756. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery. 1958;44:854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schwan A, Sjölin S, Trottestam U, Aronsson B. Relapsing clostridium difficile enterocolitis cured by rectal infusion of homologous faeces. Lancet (London, England) 1983;2:845. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kelly CR, et al. Update on Fecal Microbiota Transplantation 2015: Indications, Methodologies, Mechanisms, and Outlook. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:223–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Moore T, Rodriguez A, Bakken JS. Fecal microbiota transplantation: A practical update for the infectious disease specialist. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:541–545. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lagier JC. Faecal microbiota transplantation: from practice to legislation before considering industrialization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:1112–1118. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.N. I. for Health, C. E. I. P. Programme. Interventional procedure overview of faecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 134.Collins SM, Surette M, Bercik P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:735–742. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Woting A, Blaut M. The Intestinal Microbiota in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients. 2016;8:202. doi: 10.3390/nu8040202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ridaura VK, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science (80-) 2013;341:1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Alang N, Kelly CR. Open forum Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:761–767. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Youngster I, et al. Oral, Capsulized, Frozen Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Relapsing Clostridium difficileInfection. JAMA. 2014;312:1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kelly CR, Kunde SS, Khoruts A. Guidance on preparing an investigational new drug application for fecal microbiota transplantation studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Orenstein R, et al. Safety and Durability of RBX2660 (Microbiota Suspension) for Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection: Results of the PUNCH CD Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:596–602. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Schwartz M, Gluck M, Koon S. Norovirus gastroenteritis after fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection despite asymptomatic donors and lack of sick contacts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1367. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lee CH, et al. Frozen vs Fresh Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Clinical Resolution of Diarrhea in Patients With Recurrent Clostridium difficileInfection. JAMA. 2016;315:142–148. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Agrawal M, et al. The Long-term Efficacy and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Recurrent, Severe, and Complicated Clostridium difficile Infection in 146 Elderly Individuals. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:403–407. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Pierog A, Mencin A, Reilly NR. Fecal microbiota transplantation in children with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:1198–200. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Aas J, Gessert CE, Bakken JS. Recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: case series involving 18 patients treated with donor stool administered via a nasogastric tube. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:580–585. doi: 10.1086/367657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Kelly CR, de Leon L, Jasutkar N. Fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in 26 patients: methodology and results. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:145–9. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318234570b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kassam Z, Hundal R, Marshall JK, Lee CH. Fecal transplant via retention enema for refractory or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:191–193. doi: 10.1001/archinte.172.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kassam Z, Lee CH, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:500–508. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]