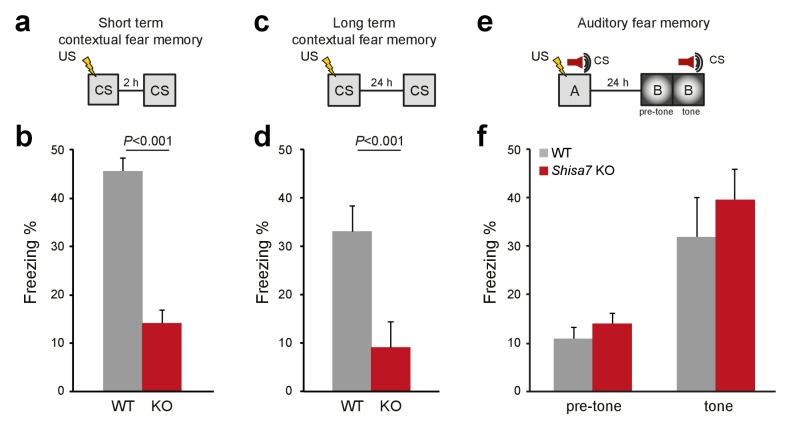

Figure 7. Deletion of Shisa7 specifically affects contextual fear memory.

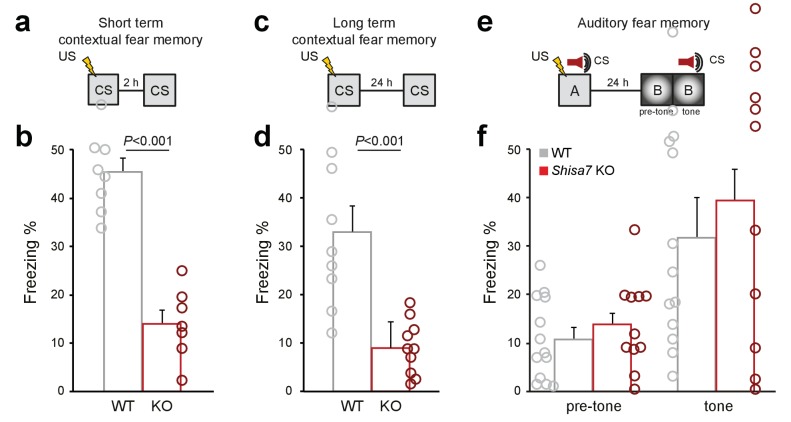

(a,c) Experimental set-up of measuring contextual fear conditioning memory (a,c), in which mice received a foot shock (US) in a specific environment (CS), and freezing was assessed upon re-exposure to the CS 2 hr, or 24 hr later to measure short term and long term contextual fear memory, respectively. (b,d) For Shisa7 KO mice, both a short term fear memory deficit (nWT = 8, nKO = 7; unpaired t-test, p<0.001; (b), as well as a long term fear memory deficit (nWT = 9 nKO = 10; Mann-Whitney U-test, p=0.001; (d) were observed. (e) Experimental set-up of measuring auditory fear conditioning memory, in which a 30 s tone co-terminated with a foot shock and memory was tested 24 hr after conditioning in a novel environment to measure generalization of fear (pre-tone), and the auditory fear memory in response to cue presentation (tone). (f) Auditory fear memory was not affected by genotype (nWT = 13, nKO = 12; ANOVA, F(1,23)=0.733 p=0.401). Individual data is shown in Figure 7—figure supplement 1.