Abstract

Background

Previous reports have shown that overall incidence of malignant brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tumors varied significantly by country. The aim of this study was to estimate histology-specific incidence rates by global region and assess incidence variation by histology and age.

Methods

Using data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s (IARC) Cancer Incidence in Five Continents X (including over 300 cancer registries), we calculated the age-adjusted incidence rates (AAIR) per 100000 person-years and 95% CIs for brain and other CNS tumors overall and by age groups and histology.

Results

There were significant differences in incidence by region. Overall incidence of malignant brain tumors per 100000 person-years in the US was 5.74 (95% CI = 5.71–5.78). Incidence was lowest in Southeast Asia (AAIR = 2.55, 95% CI = 2.44–2.66), India (AAIR = 2.85, 95% CI = 2.78–2.93), and East Asia (AAIR = 3.07, 95% CI = 3.02–3.12). Incidence was highest in Northern Europe (AAIR = 6.59, 95% CI = 6.52–6.66) and Canada (AAIR = 6.53, 95% CI = 6.41–6.66). Astrocytic tumors showed the broadest variation in incidence regionally across the globe.

Conclusion

Brain and other CNS tumors are a significant source of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide. Regional differences in incidence may provide clues toward genetic or environmental causes as well as a foundation for broadening knowledge of their epidemiology. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiology of malignant brain tumors globally is critical to researchers, public health officials, disease interest groups, and clinicians and contributes to collaborative efforts in future research.

Keywords: brain tumors, cancer registries, central nervous system tumors, global incidence, incidence

Importance of the study

The incidence of most malignant brain and other CNS tumors is significantly lower in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and India. The highest incidences have been found in Europe, Canada, the United States, and Australia. This study used cancer registries from IARC and CBTRUS to compare the incidence of selected histologies of malignant brain and CNS tumors in 13 global regions. Astrocytic tumors had the broadest distribution of incidence globally in all age groups, while medulloblastoma and other embryonal tumors had the least variation in incidence. The significant difference in incidence in Asian populations and European populations indicates the possible influence of ancestry or environmental factors in malignant brain and CNS tumors.

Primary malignant brain and other CNS tumors are rare, accounting for 1.4% of new cancer diagnoses in the United States and 2.7% of deaths due to cancer.1 Though brain and other CNS tumors are rare, they cause morbidity and mortality that is disproportionate to their incidence. Brain and other CNS tumors are heterogeneous and can be categorized into 29 histologic groups according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the CNS.2–4 Incidence varies significantly by histology, with gliomas (including astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and ependymal tumors) accounting for the largest proportion of malignant brain tumors.2 Histologic types vary significantly in their demographic patterns of incidence, treatment regimens, and prognosis after diagnosis. There are no validated risk factors that account for a large proportion of brain and other CNS tumor cases.5,6

The global variation in incidence of primary malignant brain and other CNS tumors has been well described in previous analyses,7,8 but few analyses have examined international patterns of incidence by histology. Histology-specific incidence patterns vary by demographic group, and it is likely that these may not follow the same global distribution as overall incidence. Previous estimates have been of highly heterogeneous incidence, likely due to regional differences in diagnostic capabilities and reporting methods.9,10 Details about the histology-specific incidence variations have not been addressed. The aim of this study is to use available international data to characterize the histology-specific incidence variation by global region. This analysis represents the most up-to-date histology-specific estimation of global primary malignant brain and other CNS tumor incidence. A better understanding of geographical variations in brain tumor incidence may highlight potential risk factors and etiology and provide guidance in the allocation of health resources.

Materials and Methods

This analysis was approved by the University Hospitals Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Data for this analysis were obtained from 2 sources. Data for all non-US regions were generated using the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s (IARC) Cancer Incidence in Five Continents X (CI5-X),8 which includes data from 290 cancer registries from 68 countries. Incidence rates (IRs) for the US were generated using the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) analytic file from 2003–2007, which includes data from 51 central cancer registries (50 states and the District of Columbia, ~99.9% of the US population) and represents the most complete source of US cancer registry data for brain and other CNS tumors.2

Registry data were categorized into 13 global regions, modeled after those used by the World Bank (http://www.worldbank.org/en/country) and the United Nations (http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm). The 13 regions included: US, Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Martinique, Jamaica, and Uruguay), Northern Europe (including the United Kingdom, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Russian Federation, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic), Southern Europe (Malta, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia), the Middle East and Northern Africa (Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Iran, Israel, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Cyprus, and Turkey), Southeast Africa (Malawi, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Uganda), India, East Asia (China, Japan, Republic of Korea, and Singapore), Southeast Asia (Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand), and Australia/New Zealand (Supplementary Table S1).

Histologies were defined using the site and histology codes of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3)11 (Supplementary Table S2). Only malignant tumors were included in this analysis, as nonmalignant brain and CNS tumors are not consistently collected by all global registries.

Age-adjusted incidence rates (AAIR)/100000 population with 95% CIs were calculated for selected histologies by age groups (children ages 0–14, adolescents and young adults [AYA] ages 15–39, and older adults ages 40+) and region. Age-adjusted rates for the US using the CBTRUS database were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.3.2.12 Age-specific rates for the CI5-X dataset were generated using SAS 9.4 and R 3.2.3.15 All rates were adjusted to the WHO Standard Million using 5-year age groups. Confidence intervals were generated using the method described by Tiwari et al14 using the R package “asht.”15 Groups with a count of cases <16 were excluded, as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries’ agreement with CBTRUS. Figures were generated using the R 3.2.313 packages ggplot2,16 maptools,17 rgdal,18 and rgeos.19

Results

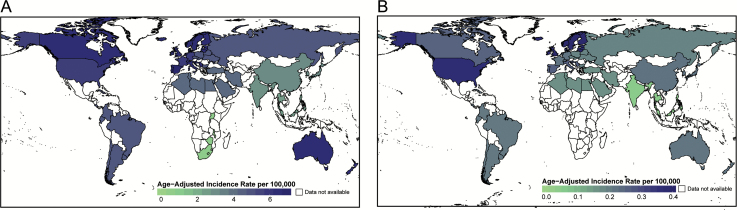

Overall global incidence of malignant brain tumors was 5.57/100000 (95% CI = 5.55–5.60), and incidence of these tumors was highest in adults (Table 1). The IRs of all malignant brain tumors varied significantly among the 13 regions. The highest incidence was found in Southern Europe (AAIR = 6.89, 95% CI = 6.78–6.99), Northern Europe (AAIR = 6.59, 95% CI = 6.52–6.66), and Canada (AAIR = 6.53, 95% CI = 6.41–6.66) (Fig. 1A, Table 1). The lowest IRs were found in Southeast Asia (AAIR = 2.55, 95% CI = 2.44–2.66), India (AAIR = 2.85, 95% CI = 2.78–2.93), and East Asia (AAIR = 3.07, 95% CI = 3.02–3.12).

Table 1.

Counts and age-adjusted incidence ratesa of malignant brain and other CNS tumors by region, site, and age group (CBTRUS and CI5-X, 2003–2007)

| Site and Region | All Ages | Children (0–14) | AYA (15–39) | Older Adults (40+) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | |

| Brain | ||||||||||||

| Global | 264 241 | 5.57 | 5.55–5.60 | 19 852 | 2.28 | 2.25–2.32 | 39 494 | 2.35 | 2.33–2.37 | 204 895 | 11.75 | 11.69–11.80 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 8272 | 6.38 | 6.24–6.53 | 453 | 1.88 | 1.71–2.06 | 1131 | 2.57 | 2.42–2.72 | 6688 | 14.15 | 13.81–14.5 |

| Canada | 11 386 | 6.53 | 6.41–6.66 | 758 | 2.70 | 2.51–2.90 | 1478 | 2.61 | 2.47–2.74 | 9150 | 13.91 | 13.62–14.2 |

| East Asia | 16 279 | 3.07 | 3.02–3.12 | 1469 | 1.77 | 1.68–1.87 | 3008 | 1.49 | 1.43–1.54 | 11 802 | 5.86 | 5.75–5.97 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 25 761 | 4.82 | 4.76–4.89 | 1508 | 2.25 | 2.13–2.36 | 4266 | 2.51 | 2.43–2.58 | 19 987 | 9.42 | 9.29–9.55 |

| India | 5578 | 2.85 | 2.78–2.93 | 770 | 1.17 | 1.09–1.26 | 1670 | 1.51 | 1.43–1.58 | 3138 | 5.67 | 5.47–5.88 |

| Latin America | 6979 | 4.87 | 4.75–4.99 | 869 | 1.95 | 1.82–2.09 | 1429 | 1.96 | 1.86–2.07 | 4681 | 10.40 | 10.09–10.71 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 5587 | 4.21 | 4.09–4.32 | 768 | 1.77 | 1.64–1.90 | 1148 | 1.73 | 1.64–1.84 | 3671 | 8.88 | 8.59–9.17 |

| Northern Europe | 36 941 | 6.59 | 6.52–6.66 | 1794 | 2.11 | 2.01–2.21 | 4593 | 2.73 | 2.65–2.81 | 30 554 | 14.40 | 14.23–14.56 |

| Southeast Asia | 2686 | 2.55 | 2.44–2.66 | 478 | 1.42 | 1.30–1.55 | 668 | 1.13 | 1.05–1.22 | 1540 | 5.02 | 4.75–5.30 |

| Southeast Africa | 125 | 0.71 | 0.57–0.88 | 45 | 0.46 | 0.33–0.61 | 38 | 0.34 | 0.23–0.47 | 42 | 1.34 | 0.96–1.82 |

| Southern Europe | 19 443 | 6.89 | 6.78–6.99 | 751 | 2.37 | 2.20–2.54 | 2156 | 2.73 | 2.61–2.85 | 16 536 | 15.06 | 14.83–15.29 |

| United States | 101 243 | 5.74 | 5.71–5.78 | 9116 | 3.03 | 2.97–3.09 | 14 959 | 2.88 | 2.84–2.93 | 77 168 | 11.06 | 10.98–11.14 |

| Western Europe | 23 961 | 5.84 | 5.77–5.92 | 1073 | 2.00 | 1.88–2.13 | 2950 | 2.53 | 2.44–2.62 | 19 938 | 12.54 | 12.36–12.72 |

| Other parts of central nervous system | ||||||||||||

| Global | 12 542 | 0.28 | 0.28–0.29 | 2371 | 0.28 | 0.27–0.29 | 2689 | 0.16 | 0.15–0.17 | 7482 | 0.42 | 0.41–0.43 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 257 | 0.22 | 0.19–0.25 | 57 | 0.24 | 0.18–0.31 | 59 | 0.14 | 0.10–0.18 | 141 | 0.29 | 0.24–0.34 |

| Canada | 384 | 0.25 | 0.23–0.28 | 91 | 0.33 | 0.27–0.41 | 93 | 0.16 | 0.13–0.20 | 200 | 0.29 | 0.25–0.33 |

| East Asia | 1237 | 0.22 | 0.21–0.24 | 95 | 0.12 | 0.10–0.15 | 292 | 0.14 | 0.13–0.16 | 850 | 0.39 | 0.37–0.42 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 933 | 0.19 | 0.18–0.20 | 104 | 0.16 | 0.13–0.19 | 215 | 0.13 | 0.11–0.14 | 614 | 0.29 | 0.27–0.32 |

| India | 96 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 20 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | 27 | 0.02 | 0.02–0.04 | 49 | 0.09 | 0.07–0.12 |

| Latin America | 307 | 0.21 | 0.19–0.24 | 56 | 0.13 | 0.10–0.16 | 71 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.12 | 180 | 0.41 | 0.35–0.47 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 248 | 0.17 | 0.15–0.19 | 72 | 0.17 | 0.13–0.21 | 82 | 0.12 | 0.10–0.15 | 94 | 0.22 | 0.18–0.27 |

| Northern Europe | 1952 | 0.39 | 0.37–0.41 | 272 | 0.32 | 0.28–0.36 | 376 | 0.22 | 0.20–0.25 | 1304 | 0.63 | 0.59–0.66 |

| Southeast Asia | 57 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | – | – | – | 19 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | 34 | 0.10 | 0.07–0.15 |

| Southeast Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 631 | 0.26 | 0.24–0.28 | 74 | 0.23 | 0.18–0.29 | 115 | 0.15 | 0.12–0.18 | 442 | 0.42 | 0.38–0.46 |

| United States | 5703 | 0.37 | 0.36–0.38 | 1380 | 0.46 | 0.44–0.49 | 1184 | 0.23 | 0.22–0.24 | 3139 | 0.47 | 0.46–0.49 |

| Western Europe | 728 | 0.22 | 0.20–0.24 | 146 | 0.28 | 0.23–0.32 | 152 | 0.13 | 0.11–0.16 | 430 | 0.28 | 0.25–0.30 |

| Meninges | ||||||||||||

| Global | 10 321 | 0.21 | 0.21–0.22 | 177 | 0.02 | 0.02–0.02 | 1014 | 0.06 | 0.06–0.06 | 9130 | 0.53 | 0.52–0.54 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 177 | 0.13 | 0.11–0.16 | – | – | – | 21 | 0.05 | 0.03–0.07 | 156 | 0.34 | 0.28–0.39 |

| Canada | 335 | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 | – | – | – | 35 | 0.06 | 0.04–0.08 | 295 | 0.47 | 0.41–0.52 |

| East Asia | 2248 | 0.40 | 0.38–0.42 | 21 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | 150 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.08 | 2077 | 1.05 | 1.01–1.10 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 1617 | 0.28 | 0.27–0.30 | 17 | 0.03 | 0.01–0.04 | 194 | 0.11 | 0.10–0.13 | 1406 | 0.67 | 0.64–0.71 |

| India | 102 | 0.06 | 0.05–0.08 | – | – | – | 18 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 | 81 | 0.16 | 0.12–0.20 |

| Latin America | 419 | 0.29 | 0.27–0.33 | 54 | 0.12 | 0.09–0.16 | 76 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.13 | 289 | 0.64 | 0.57–0.72 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 162 | 0.13 | 0.11–0.15 | – | – | – | 15 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.04 | 141 | 0.34 | 0.29–0.40 |

| Northern Europe | 768 | 0.13 | 0.13–0.15 | – | – | – | 86 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 674 | 0.33 | 0.30–0.35 |

| Southeast Asia | 103 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.13 | – | – | – | 16 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | 86 | 0.27 | 0.21–0.33 |

| Southeast Africa | 15 | 0.13 | 0.07–0.21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 982 | 0.33 | 0.31–0.35 | – | – | – | 78 | 0.09 | 0.07–0.12 | 894 | 0.82 | 0.77–0.88 |

| United States | 2630 | 0.13 | 0.13–0.14 | 44 | 0.01 | 0.01–0.02 | 258 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 2328 | 0.32 | 0.31–0.33 |

| Western Europe | 763 | 0.18 | 0.17–0.19 | – | – | – | 63 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | 693 | 0.45 | 0.42–0.49 |

–Categories with fewer than 16 cases were suppressed.

aRates are per 100000 persons and are age adjusted to the World Health Organization Standard Million.

Abbreviations: AAAIR: average annual age adjusted incidence rate; AYA: adolescents and young adults ages 15–39.

Fig. 1.

Age-adjusted incidence of (A) malignant brain tumors and (B) malignant tumors of the non-brain CNS (CBTRUS and CI5-X, 2003–2007).

The variation in IR for other malignant CNS tumors (including spine, cranial nerves, and nonspecific nervous system locations) was also investigated. Overall global incidence of these tumors was 0.28/100000 (95% CI = 0.27–0.29) and was highest in adults 40+ (Table 1). The highest IRs for these tumors were found in Northern Europe (AAIR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.37–0.41) and the US (AAIR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.36–0.38) (Fig. 1B, Table 1). The lowest IRs were found in India (AAIR = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.04–0.06) and Southeast Asia (AAIR = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.04–0.07).

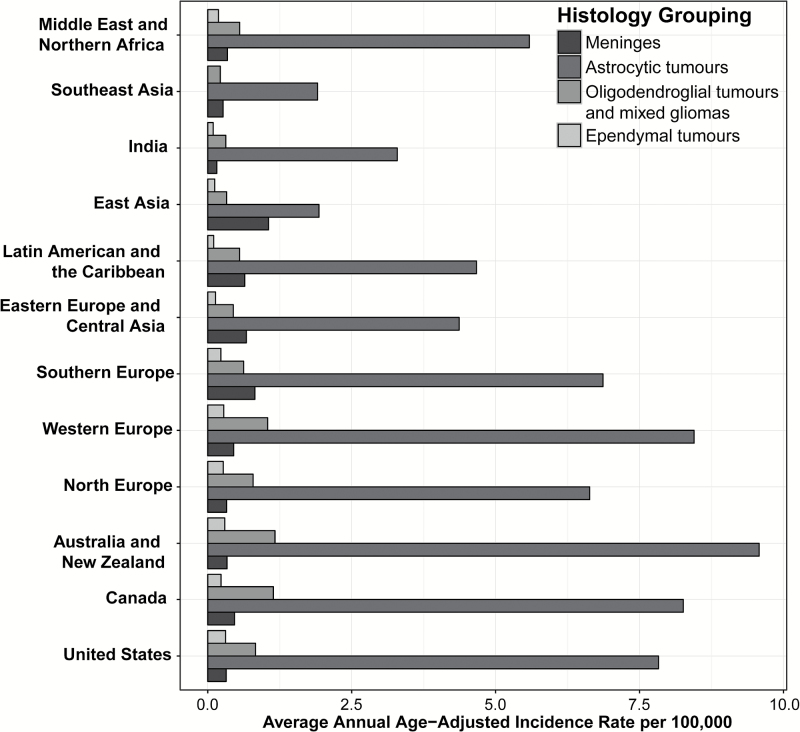

The most common histology worldwide was the astrocytic tumor group, followed by oligodendroglial and other mixed gliomas, and malignant meningiomas. Overall incidence of astrocytic tumors was 2.98/100000 (95% CI = 2.96–3.00), and incidence of these tumors was highest in adults 40+ (Table 2). IRs of astrocytic tumors varied significantly between regions. For patients age 40 years or older, Australia (AAIR = 9.58, 95% CI = 9.30–9.86), Western Europe (AAIR = 8.45, 95% CI = 8.3–8.59), and Canada (AAIR = 8.26, 95% CI = 8.04–8.48) had the highest IRs. The lowest IRs were found in Southeast Asia (AAIR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.75–2.08) and East Asia (AAIR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.87–1.99).

Table 2.

Counts and age-adjusted incidence ratesa of malignant brain and other CNS tumors by region, histology, and age group (CBTRUS and CI5-X, 2003–2007)

| Histology and Region | All Ages | Children (0–14) | AYA (15–39) | Older Adults (40+) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | Count | AAAIR | 95% CI | |

| Astrocytic tumors | ||||||||||||

| Global | 146 621 | 2.98 | 2.97–3.00 | 6595 | 0.75 | 0.73–0.77 | 19 277 | 1.14 | 1.13–1.16 | 120 749 | 6.77 | 6.73–6.81 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 5363 | 3.94 | 3.83–4.05 | 92 | 0.38 | 0.31–0.46 | 606 | 1.36 | 1.26–1.48 | 4665 | 9.58 | 9.30–9.86 |

| Canada | 6603 | 3.58 | 3.49–3.67 | 313 | 1.10 | 0.98–1.23 | 637 | 1.13 | 1.04–1.22 | 5653 | 8.26 | 8.04–8.48 |

| East Asia | 5539 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | 259 | 0.30 | 0.26–0.34 | 1127 | 0.54 | 0.51–0.58 | 4153 | 1.93 | 1.87–1.99 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 12 018 | 2.21 | 2.17–2.25 | 481 | 0.70 | 0.64–0.77 | 2260 | 1.33 | 1.27–1.38 | 9277 | 4.37 | 4.28–4.46 |

| India | 2833 | 1.50 | 1.45–1.56 | 176 | 0.26 | 0.22–0.30 | 845 | 0.76 | 0.71–0.81 | 1812 | 3.29 | 3.14–3.45 |

| Latin America | 3070 | 2.09 | 2.01–2.16 | 215 | 0.48 | 0.42–0.55 | 647 | 0.89 | 0.82–0.96 | 2208 | 4.67 | 4.47–4.87 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 3096 | 2.39 | 2.31–2.48 | 234 | 0.54 | 0.47–0.61 | 544 | 0.83 | 0.76–0.90 | 2318 | 5.59 | 5.36–5.82 |

| Northern Europe | 17 477 | 2.98 | 2.94–3.03 | 501 | 0.58 | 0.53–0.64 | 2326 | 1.38 | 1.32–1.43 | 14 650 | 6.63 | 6.53–6.74 |

| Southeast Asia | 996 | 0.93 | 0.87–0.99 | 101 | 0.30 | 0.25–0.37 | 288 | 0.49 | 0.43–0.55 | 607 | 1.91 | 1.75–2.08 |

| Southeast Africa | 22 | 0.13 | 0.07–0.21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 8822 | 3.01 | 2.95–3.08 | 199 | 0.63 | 0.54–0.72 | 986 | 1.22 | 1.15–1.30 | 7637 | 6.86 | 6.71–7.02 |

| United States | 65 305 | 3.59 | 3.56–3.62 | 3754 | 1.24 | 1.20–1.28 | 7405 | 1.43 | 1.39–1.46 | 54 146 | 7.83 | 7.77–7.90 |

| Western Europe | 15 642 | 3.59 | 3.53–3.65 | 274 | 0.50 | 0.45–0.57 | 1620 | 1.38 | 1.31–1.45 | 13 748 | 8.45 | 8.30–8.59 |

| Oligodendroglial tumors and mixed gliomas | ||||||||||||

| Global | 20 676 | 0.43 | 0.42–0.43 | 547 | 0.06 | 0.06–0.07 | 7118 | 0.42 | 0.41–0.43 | 13 011 | 0.71 | 0.70–0.73 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 849 | 0.64 | 0.60–0.69 | 16 | 0.07 | 0.04–0.11 | 255 | 0.57 | 0.50–0.65 | 578 | 1.17 | 1.07–1.27 |

| Canada | 1226 | 0.67 | 0.64–0.71 | – | – | – | 400 | 0.69 | 0.62–0.76 | 815 | 1.14 | 1.06–1.22 |

| East Asia | 1174 | 0.20 | 0.19–0.21 | 28 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | 416 | 0.19 | 0.18–0.21 | 730 | 0.33 | 0.30–0.35 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 1365 | 0.26 | 0.25–0.28 | 43 | 0.06 | 0.04–0.08 | 403 | 0.24 | 0.21–0.26 | 919 | 0.44 | 0.41–0.47 |

| India | 388 | 0.18 | 0.16–0.20 | 21 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | 171 | 0.16 | 0.13–0.18 | 196 | 0.31 | 0.27–0.36 |

| Latin America | 465 | 0.29 | 0.27–0.32 | 18 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 | 172 | 0.24 | 0.20–0.28 | 275 | 0.55 | 0.49–0.62 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 439 | 0.31 | 0.28–0.34 | 21 | 0.05 | 0.03–0.07 | 177 | 0.27 | 0.23–0.31 | 241 | 0.55 | 0.49–0.63 |

| Northern Europe | 2425 | 0.45 | 0.44–0.47 | 57 | 0.07 | 0.05–0.09 | 717 | 0.42 | 0.39–0.45 | 1651 | 0.79 | 0.75–0.83 |

| Southeast Asia | 132 | 0.11 | 0.09–0.14 | – | – | – | 51 | 0.09 | 0.06–0.11 | 73 | 0.22 | 0.17–0.28 |

| Southeast Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 965 | 0.37 | 0.34–0.39 | – | – | – | 303 | 0.36 | 0.32–0.40 | 648 | 0.62 | 0.57–0.67 |

| United States | 8922 | 0.56 | 0.55–0.57 | 253 | 0.08 | 0.07–0.09 | 3384 | 0.65 | 0.62–0.67 | 5285 | 0.83 | 0.80–0.85 |

| Western Europe | 2365 | 0.61 | 0.59–0.64 | 55 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.13 | 685 | 0.57 | 0.53–0.62 | 1625 | 1.04 | 0.99–1.09 |

| Ependymal tumors | ||||||||||||

| Global | 8565 | 0.19 | 0.19–0.20 | 1838 | 0.21 | 0.20–0.22 | 2411 | 0.14 | 0.14–0.15 | 4316 | 0.24 | 0.23–0.24 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 275 | 0.23 | 0.20–0.26 | 52 | 0.22 | 0.16–0.29 | 75 | 0.18 | 0.14–0.22 | 148 | 0.30 | 0.25–0.35 |

| Canada | 326 | 0.21 | 0.19–0.23 | 64 | 0.23 | 0.18–0.30 | 97 | 0.17 | 0.14–0.21 | 165 | 0.23 | 0.20–0.27 |

| East Asia | 569 | 0.12 | 0.11–0.13 | 125 | 0.16 | 0.14–0.20 | 170 | 0.08 | 0.07–0.10 | 274 | 0.12 | 0.11–0.14 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 602 | 0.14 | 0.13–0.16 | 133 | 0.20 | 0.17–0.24 | 189 | 0.11 | 0.10–0.13 | 280 | 0.13 | 0.12–0.15 |

| India | 158 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.08 | 50 | 0.08 | 0.06–0.10 | 53 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 55 | 0.09 | 0.07–0.12 |

| Latin America | 214 | 0.13 | 0.11–0.15 | 94 | 0.21 | 0.17–0.26 | 68 | 0.09 | 0.07–0.12 | 52 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.14 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 245 | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 | 83 | 0.19 | 0.15–0.24 | 82 | 0.12 | 0.10–0.15 | 80 | 0.19 | 0.15–0.23 |

| Northern Europe | 1027 | 0.22 | 0.20–0.23 | 208 | 0.25 | 0.21–0.28 | 254 | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 | 565 | 0.27 | 0.25–0.29 |

| Southeast Asia | 51 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.05 | 19 | 0.06 | 0.03–0.09 | 20 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | – | – | – |

| Southeast Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 432 | 0.20 | 0.18–0.22 | 72 | 0.23 | 0.18–0.29 | 120 | 0.16 | 0.13–0.19 | 240 | 0.23 | 0.20–0.26 |

| United States | 3886 | 0.26 | 0.25–0.27 | 794 | 0.27 | 0.25–0.28 | 1080 | 0.21 | 0.20–0.22 | 2012 | 0.31 | 0.30–0.33 |

| Western Europe | 776 | 0.23 | 0.22–0.25 | 141 | 0.26 | 0.22–0.31 | 202 | 0.18 | 0.15–0.2 | 433 | 0.28 | 0.25–0.31 |

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||||||

| Global | 5933 | 0.16 | 0.16–0.17 | 3842 | 0.44 | 0.43–0.46 | 1660 | 0.10 | 0.10–0.11 | 431 | 0.02 | 0.02–0.03 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 172 | 0.18 | 0.15–0.20 | 111 | 0.46 | 0.38–0.56 | 48 | 0.12 | 0.08–0.15 | – | – | – |

| Canada | 197 | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 | 114 | 0.41 | 0.34–0.49 | 51 | 0.09 | 0.07–0.12 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.06 |

| East Asia | 421 | 0.12 | 0.11–0.14 | 314 | 0.38 | 0.34–0.43 | 94 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | – | – | – |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 594 | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 | 340 | 0.51 | 0.46–0.57 | 181 | 0.11 | 0.09–0.12 | 73 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.05 |

| India | 271 | 0.11 | 0.09–0.12 | 196 | 0.30 | 0.26–0.35 | 66 | 0.06 | 0.04–0.07 | – | – | – |

| Latin America | 333 | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 | 220 | 0.49 | 0.43–0.56 | 95 | 0.13 | 0.10–0.16 | 18 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 279 | 0.17 | 0.15–0.19 | 180 | 0.41 | 0.36–0.48 | 81 | 0.12 | 0.10–0.15 | 18 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 |

| Northern Europe | 571 | 0.16 | 0.15–0.18 | 383 | 0.45 | 0.41–0.50 | 149 | 0.09 | 0.08–0.11 | 39 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 |

| Southeast Asia | 146 | 0.11 | 0.10–0.13 | 118 | 0.35 | 0.29–0.42 | 16 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | – | – | – |

| Southeast Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 314 | 0.22 | 0.20–0.25 | 182 | 0.58 | 0.50–0.67 | 111 | 0.16 | 0.13–0.19 | 21 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 |

| United States | 2210 | 0.18 | 0.17–0.19 | 1422 | 0.48 | 0.45–0.5 | 636 | 0.13 | 0.12–0.14 | 152 | 0.02 | 0.02–0.03 |

| Western Europe | 421 | 0.18 | 0.17–0.20 | 258 | 0.48 | 0.42–0.54 | 132 | 0.13 | 0.11–0.15 | 31 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 |

| Other embryonal tumors | ||||||||||||

| Global | 3121 | 0.09 | 0.08–0.09 | 1856 | 0.22 | 0.21–0.23 | 715 | 0.04 | 0.04–0.05 | 550 | 0.03 | 0.03–0.03 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 101 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.13 | 67 | 0.28 | 0.22–0.36 | 22 | 0.05 | 0.03–0.08 | – | – | – |

| Canada | 122 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.12 | 69 | 0.25 | 0.20–0.32 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.08 | 23 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 |

| East Asia | 255 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.08 | 135 | 0.18 | 0.15–0.21 | 64 | 0.03 | 0.03–0.04 | 56 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 192 | 0.06 | 0.05–0.07 | 87 | 0.14 | 0.11–0.17 | 51 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | 54 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.03 |

| India | 108 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 62 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.13 | 30 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | 16 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 |

| Latin America | 120 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.09 | 66 | 0.15 | 0.12–0.19 | 38 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | 16 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 127 | 0.08 | 0.07–0.09 | 75 | 0.17 | 0.14–0.22 | 35 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | 17 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 |

| Northern Europe | 330 | 0.09 | 0.08–0.10 | 168 | 0.20 | 0.17–0.23 | 87 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | 75 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.04 |

| Southeast Asia | 55 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.06 | 35 | 0.10 | 0.07–0.14 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southeast Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Southern Europe | 155 | 0.09 | 0.08–0.11 | 64 | 0.20 | 0.16–0.26 | 42 | 0.06 | 0.04–0.08 | 49 | 0.05 | 0.03–0.06 |

| United States | 1341 | 0.11 | 0.10–0.12 | 914 | 0.31 | 0.29–0.33 | 248 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 179 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.03 |

| Western Europe | 243 | 0.10 | 0.09–0.11 | 134 | 0.26 | 0.21–0.30 | 55 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 54 | 0.03 | 0.03–0.05 |

–Categories with fewer than 16 cases were suppressed.

aRates are per 100000 persons and are age adjusted to the World Health Organization Standard Million.

Abbreviations: AAAIR: average annual age-adjusted incidence rate; AYA: adolescents and young adults ages 15–39.

Overall incidence of oligodendroglial and mixed gliomas was 0.71/100000 (95% CI = 0.42–0.43), and incidence of these tumors was highest in adults (Table 2). The regional variation of IRs of oligodendroglial tumors and mixed gliomas followed the variation of astrocytic tumors for adults (age 40 y or older), but to a smaller degree. The highest rates were again found in Australia (AAIR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.07–1.27), Canada (AAIR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.06–1.22), and Western Europe (AAIR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.99–1.09). The lowest IRs were found in Southeast Asia (AAIR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.17–0.28), India (AAIR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.27–0.36), and East Asia (AAIR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.30–0.35).

Overall global incidence of malignant tumors of the meninges was 0.21/100000 (95% CI = 0.21–0.22) and was highest in adults 40+ (Table 1). The highest incidence of these tumors was found in East Asia (AAIR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.38–0.42). When country-specific rates were examined within this region, there was significant heterogeneity within the region. The AAIR for all ages in China (AAIR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.79–0.87) was significantly higher than that in the neighboring countries of Japan (AAIR = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.07–0.10), Singapore (AAIR = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.04–0.14), and the Republic of Korea (AAIR = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.10–0.13). China’s IR was also significantly higher than the IR in the United States (AAIR = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.13–0.14) and Australia (AAIR = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.10–0.14). Southern Europe had the second highest regional IR (AAIR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.31–0.35) of malignant meningioma. However, the IRs for this region were elevated in 2 countries: Serbia (AAIR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.69–0.88) and Croatia (AAIR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.62–0.81). These IRs were significantly higher than those in the other countries in this region, including Spain (AAIR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.14–0.21), Italy (AAIR = 0.15, 95% CI = 0.13–0.17), and Slovenia (AAIR = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.07–0.21). Australia and New Zealand, as a region, stood out as having a particularly low IR of malignant meningioma (AAIR = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.09–0.13) in comparison to the region’s higher rates of other malignant brain and other CNS tumors.

Overall incidence of ependymal tumors was 0.19/100000 (95% CI = 0.19–0.20) (Table 2). In all regions, ependymal tumors showed a bimodal distribution in children (age 0–14 y, global AAIR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.20–0.22) and adults (age 40+ y, global AAIR = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.23–0.24). The variation of IRs for ependymal tumors was similar to that of the other gliomas, but Northern Europe replaced Western Europe as having the highest IRs. The highest IRs were found in the United States (AAIR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.25–0.27), Australia (AAIR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.20–0.26), and Northern Europe (AAIR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.20–0.23). The lowest IRs were found in Southeast Asia (AAIR = 0.04, 95% CI = 0.03–0.05) and India (AAIR = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.06–0.08).

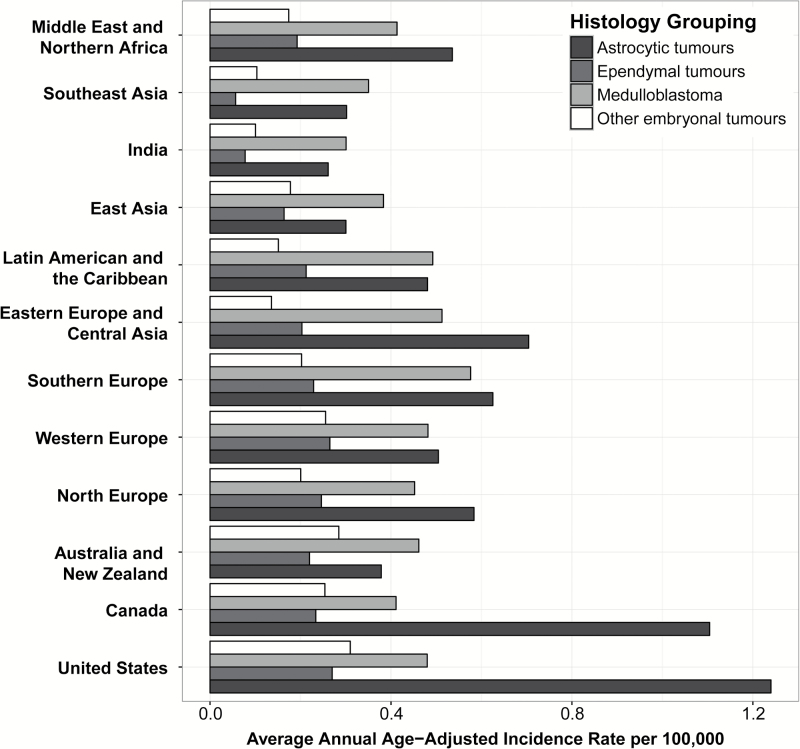

The most common tumor histology globally among children age 0–14 years was the astrocytic tumor group (AAIR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.73–0.77), followed by medulloblastoma (AAIR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.43–0.76) and other embryonal tumors (AAIR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.21–0.23) (Table 2). There was less variation among regions for these histologies (Fig. 2, Table 2). The lowest IRs of medulloblastoma in children (age 0–14 y) were found in India (AAIR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.26–0.35) and Southeast Asia (AAIR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.29–0.42), while the highest IRs of medulloblastoma were found in Southern Europe (AAIR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.50–0.67) and Eastern Europe (AAIR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.46–0.57). The IRs of other embryonal tumors were consistent among regions.

Fig. 2.

Age-adjusted incidence of selected malignant brain tumor histologies by global region for age group 0–14 years (CBTRUS and CI5-X, 2003–2007).

The greatest variation in IR for children (age 0–14 y) was for astrocytic tumors. The United States (AAIR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.20–1.28) and Canada (AAIR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.98–1.23) had significantly higher IRs for this age group than other regions. In contrast, Australia/New Zealand (AAIR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.31–0.46), which interestingly had among the highest IRs of gliomas in age groups 15–39 and 40+ years, had a relatively low IR of malignant brain and other CNS tumors in children (age 0–14 y).

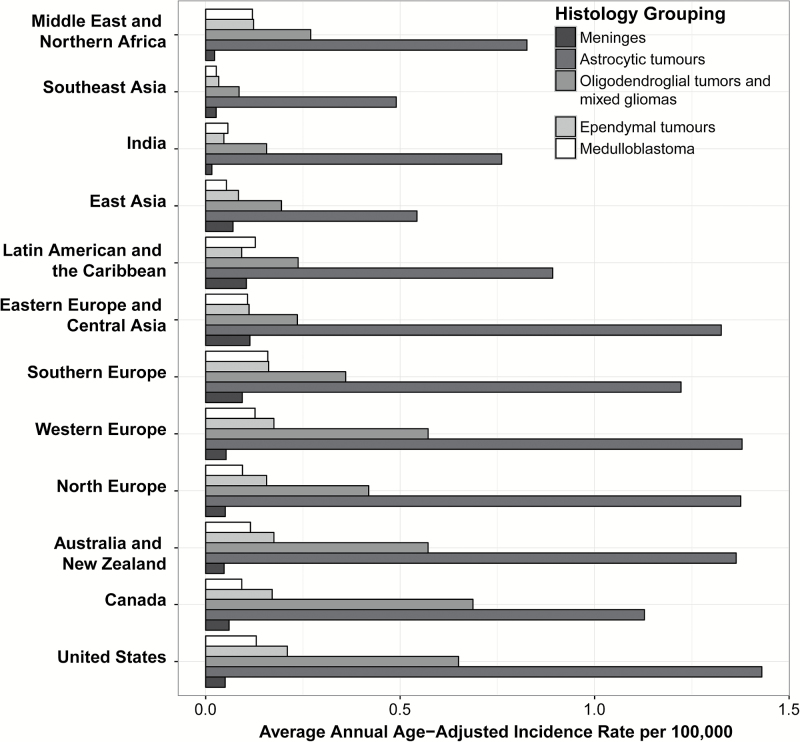

Astrocytic tumors were the most common histology among AYA, with incidence of 1.14/100000 (95% CI = 1.13–1.16) (Fig. 3, Table 2). Incidence of these tumors among AYA was highest in the United States (AAIR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.39–1.46), Northern Europe (AAIR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.32–1.43), and Western Europe (AAIR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.31–1.45) (Fig. 3). Incidence of these tumors was lowest in East Asia (AAIR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.51–0.58) and Southeast Asia (AAIR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.43–0.55), though astrocytic tumors were still the most common tumors in this age group in these regions.

Fig. 3.

Age-adjusted incidence of selected malignant brain tumor histologies by global region for age group 15–39 years (CBTRUS and CI5-X, 2003–2007).

Astrocytic tumors were also the most common histology among older adults age 40+ years with overall global incidence of 6.77/100000 (95% CI = 6.73–6.81) (Fig. 4, Table 2). Incidence of these tumors among older adults was highest in Australia/New Zealand (AAIR = 9.58, 95% CI = 9.30–9.86), Western Europe (AAIR = 8.45, 95% CI = 8.30–8.59), and Canada (AAIR = 8.26, 95% CI = 8.04–8.48). Incidence of astrocytic tumors was lowest in Southeast Asia (AAIR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.75–2.08) and East Asia (AAIR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.87–1.99), though astrocytic tumors were still the most common tumors in this age group in these regions.

Fig. 4.

Age-adjusted incidence of selected malignant brain tumor histologies by global region for age group 40+ years (CBTRUS and CI5-X, 2003–2007).

Discussion

This study presents a histology-specific comparison of global IRs for malignant brain and other CNS tumors. The results of this study confirm that incidence of these tumors varies significantly by country, as shown by previous analyses. A recent systematic review10 included 53 studies from all over the world and calculated the overall global incidence of brain tumors per 100000 person-years to be 10.82 (95% CI = 8.63–13.56), which is significantly higher than the incidence of brain tumors calculated by this analysis (AAIR = 5.57, 95% CI = 5.55–6.00). GLOBOCAN estimates the 2012 worldwide incidence of malignant brain and other CNS tumors to be 3.4/100000 person-years, which is significantly lower than the results of this analysis.20 A recent analysis of the CI5-X data21 calculated country-specific IRs for all malignant brain tumors, and examined trends in incidence over time (1993–2007). This analysis found increasing incidence in several countries (including in Latin America and Southern Europe). All 3 of these analyses used different methodologies and datasets to calculate these rates, and demonstrate the sensitivity of these estimates to data selection. The CI5-X data and GLOBOCAN data are both curated by IARC but are held to different standards of data quality. Registries included in CI5-X are evaluated by IARC and determined to meet specific quality standards, while GLOBOCAN includes additional registries that do not meet these standards.7,8 Systematic reviews may contain data from sources that are not population based, such as hospital series. All of these selection criteria can significantly affect presented rates.

The results of this analysis were similar to previous studies that have examined regional incidence patterns. A study of CNS cancers in Europe revealed geographical variation in astrocytic tumors, with the highest rate in the UK and Ireland (5.1/100000) and the lowest in Eastern Europe (3.1/100000).22 These rates are comparable to those calculated for Northern Europe (the category that includes the UK in this analysis) and Eastern Europe, though the rates resulting from this analysis were higher. GLOBOCAN estimated the incidence of brain and other CNS tumors in eastern Africa (18 countries) and southern Africa (5 countries) to be 1.2/100000 and 1.5/100000, respectively. This was lower than the incidence for southeast Africa (4 countries) calculated in this analysis. The count of cases in the registries used to calculate rates for this geographic group was often too small to report these rates. GLOBOCAN estimated the incidence of these tumors in eastern Asia and southeastern Asia to be 3.8/100000, and 2.3/100000, respectively, which is very similar to the results calculated by this analysis. Rates may vary significantly by country for many reasons, and choice of categorization scheme may also significantly affect rates.

There are many reasons why cancer incidence may vary globally, and it is likely that a combination of differences contribute to the variation. One of the most significant factors that affect incidence variation globally is variation in cancer registration systems and health infrastructure. Cancer registration systems and infrastructure also vary significantly by region. For several of the countries included in this analysis, cancer incidence was based on a single city’s registry and may not be representative of the country as a whole. Variation in health systems and access to care affects whether an individual is diagnosed with a brain tumor, and whether this diagnosis is reported to a cancer registry system. Regions with less access to imaging technologies such as MRI, CT, and X-ray may have lower IRs of these tumors due to underdiagnosis rather than truly lower incidence. Cancer registration data from low- and middle-income countries are significantly affected by lack of health care resources,23 leading to underestimation of incidence in these countries. A previous analysis of cancer registration quality by region in registries included in the CI5-X found that overall geographic coverage by cancer registries in Africa was 31%, with overall population coverage of 1%. It is important to consider these sources of potential bias when interpreting national or regional variation of cancer incidence. Registries included in the CI5-X set used for calculation of non-US rates in this analysis are evaluated on comparability, completeness, and quality before being included in this analytic set (see Supplementary Table S1 for more information on registry-specific quality measures for brain and CNS tumors). All registries coded cases according to the ICD-O-3 coding scheme and included only newly diagnosed primary tumors. Completeness is assessed by assessing the stability of cases over time, the proportion of cases that are histologically verified, the mortality-to-incidence ratio, and the proportion of cases diagnosed via death certificate.

It is likely that in addition to infrastructure and health care system variation, true variation in incidence of malignant brain and other CNS tumors exists between regions. Exposure to environmental risk factors, including currently unidentified risk factors, may vary significantly by region. There is no validated risk factor for brain and other CNS tumors that accounts for a large proportion of incidence cases. The only consistently associated risk factor for brain and CNS tumors is ionizing radiation to the head, which most strongly increases incidence of meningioma.24,25 Ionizing radiation may come from a variety of sources, with exposure from medical procedures being the largest. High risks of cancer have been established in certain populations with a high exposure risk, including atomic bomb survivors, nuclear workers, uranium miners, and patients undergoing repeated radiation imaging.25 Worldwide, the use of medical procedures with ionizing radiation has rapidly increased, with the highest use in well-developed countries.24 Future studies may help clarify how much of the variation in brain and CNS tumor incidence can be explained by regional differences in medical radiation usage.

History of allergies and other atopic conditions have been associated with reduced risk of gliomas.24,26 A worldwide study found high variation in the prevalence of allergic symptoms in children, with the highest asthma prevalence in English-speaking developed countries.27 This does not support the previously reported inverse relationship between allergies and glioma risk, and suggests that a more complicated relationship exists. One epidemiological study reported that mobile phone use might be a risk factor for malignant neoplasms of the CNS, although the risk was small, contributing about 1% of variation between countries.28 Recent reviews of data on cellular phone use and risk of CNS tumors in adults have not supported the association, although given the unknown latency period, continued monitoring has been warranted.24,29

There has been some evidence that meningioma risk may be associated with hormone exposure, which has been hypothesized due to these tumors being approximately twice as common in women as in men.29 International variation in age at menarche, parity, age at menopause, use of hormonal contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapy may have led to variation in estrogen exposure, which could potentially affect incidence of these tumors.

In general, incidence of malignant brain and CNS tumors was higher in North America and Europe than in Asia,2,30 a pattern that is consistent with this analysis. Due to variation by country within these regions, it is difficult to determine whether these variation patterns are a reflection of “true” incidence or a result of differences between different regions. A recent study31 compared brain and other CNS tumor incidence between the US and Taiwan and found overall IR in Taiwan to be half that of the US, which is consistent with the results of this analysis. They noted that standards for imaging for brain and CNS tumors are the same in both countries, and thus differences observed were not likely due to differences in infrastructure. This suggested that variation in risk factors (including genetic risk factors) may be related to true difference between these regions.

Previous studies had found variation by race and ethnicity in incidence of malignant brain and other CNS tumors within countries, which suggested that differences observed between regions may also be related to variation in inherited genetic risk by ancestry. While this study found significantly lower incidence of these tumors in East and Southeast Asia, previous studies within the US and UK found lower incidence of CNS tumors in Asians living in the US and UK.2,31,32 The UK National Cancer Intelligence Network estimated a lower incidence of brain and other CNS tumors at all ages for Asian ethnic groups (male: 4.0–6.5/100000; female: 2.4–4.3/100000) compared with whites (male: 8.2–8.7/100000; female: 5.3–5.6/100000). In the US, Asian-Pacific Islanders (API) had an overall incidence of malignant brain tumors of 4.14/100000 population, lower than the incidence in whites (7.20/100000 population).2 Incidence among whites in the US was more similar to the rates in Northern Europe observed in this analysis, which were higher than those observed in the US. Similar patterns were seen by histology, where astrocytic tumors were more than twice as common in whites in the US compared with API (white AAIR: 4.66, 95% CI = 4.62–4.69; API AAIR: 2.16, 95% CI = 2.04, 2.28). Malignant meningioma was also slightly more common in API (AAIR: 0.19, 95% CI = 0.16–0.23) compared with whites (AAIR: 0.16, 95% CI = 0.16–0.17).

While incidence of astrocytic tumors in the US and Canada was similar to other Western countries in AYA and older adults, incidence of these tumors was much higher in children ages 0–14. In this age group, astrocytic tumors represented 35.8% and 36.9% of all brain and other CNS tumors diagnosed in children in the US and Canada, respectively. The proportion of brain and other CNS tumors in this age group that were astrocytic tumors in all other regions ranged from 16.7% to 29.8%. There are several possible explanations for this difference. Diagnostic classifications of glioma have evolved over time, and it is possible that this could represent a regional difference in classification schemes. Health care access among children in the US and Canada could vary from that in other regions, leading these children to be more likely to be diagnosed with these tumors. Incidence calculations are dependent on both accurate case counts and accurate population estimates. Quality of population estimates for children may vary between countries, leading to overestimation or underestimation of IRs. There could also be true variation in the incidence of these tumors, due to an unknown environmental or genetic factor.

There are several potential factors that may lead to variation in incidence. It is important to remember for US statistics that race as recorded in the clinical record (which is used for cancer registration) is not identical to genetic ancestry, though it has been shown to be relatively consistent.33 Ancestry within a country or region may not have been homogeneous, but overall cancer IRs within a country are significantly skewed by predominating racial or ethnic groups.

Variations in histology-specific incidences between racial groups could point toward genetic variations that affect the pathogenesis of cancer. Some ancestral populations have carried alleles that contributed to individual risk for developing a malignant brain and other CNS tumor that were less common in other populations. The majority of studies that have attempted to discover genetic risk alleles for glioma to date have been conducted in primarily European-ancestry individuals.34–39 Allele frequencies of the risk loci identified by these analyses varied significantly by continental ancestry groups within reference databases. In the US, glioma was significantly less common in African Americans and API compared with whites,2 However, it is difficult to obtain a large enough sample size of these ancestry populations for analyses to reach genome-wide significance. Several candidate single nucleotide polymorphism studies have been conducted in East Asian populations and have found novel association loci in X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1/2 (XRCC1/3),40 zinc finger CCCH-type and G-patch domain containing (ZGPAT), solute carrier family 2 member 4 regulator (SLC2A4RG), and zinc finger and BTB domain containing 46 (ZBTB46),41 as well as validated associations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1 (RTEL1) that were previously discovered in European-ancestry populations.42 This suggests that heritable glioma risk may vary significantly by continental ancestry population, which also may contribute to the variation in incidence observed in this analysis.

This is the first histology-specific global estimation of malignant brain and other CNS tumor incidence that has been conducted to date. Only malignant tumors were included in this analysis, since the cancer collection focus of current global data includes malignant tumors only. In general, the data included in this analysis are from high-quality registries and are the averaged data collected over multiple years. Therefore, the results included in this analysis should be relatively accurate.

There were several limitations to this analysis. Limited data on histology are available globally, and there was no central pathology review utilized for confirmation of histology for included cases. Cases are included in cancer registration based on the diagnosis assigned by individual pathologists at diagnosing institutions, and there is no mechanism for confirming these diagnoses. It had previously been shown that there is significant interrater variability in histopathological diagnosis of glioma,43,44 which may lead to heterogeneity within each histologic group and is important to consider when conducting epidemiological studies.45 Additionally, the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System underwent revisions in 1993,46 2000,3 2007,47 and 2016,48 which changed diagnostic criteria for several of the histologies included in this report (including medulloblastoma and malignant meningiomas). Tumors included in this report may have been diagnosed using any of the available classifications prior to 2007 due to the schedule variation in adoption of new standards by individual physicians and medical practices. These limitations are inherent to analysis of brain tumor data collected by cancer registries, and utilizing data from international registries may increase the degree of bias attributable to these factors.

Criteria for inclusion of a case in cancer registration may vary by region, though all registries included in CI5-X are required to report only newly diagnosed primary tumors. Some tumors may be diagnosed based only on radiography and receive no further treatment, which may result in assignment of an incorrect histology. Autopsies may be more common in some regions than others, and this may affect the overall incidence of malignant brain tumor. The public access CI5-X dataset does not include data on the type of diagnosis used for each individual case but does provide indices of data quality (including proportions of histologically verified [MV] and death certificate only [DCO] cases) by registry. For brain and other CNS tumors, proportion of DCO cases is highest in Central and South America. In almost all registries, the proportion of MV cases is >60%. Mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) are also provided for all registries, which measure the proportion of deaths for each diagnosed case. MIR >100% would suggest that incident cases are being missed by the registry. MIRs for the majority of registries included in this analysis range from 65% to 80%, which is consistent with known patterns of mortality from malignant brain tumor. For several tumor types, diagnostic procedures have become increasingly reliant on molecular characterization, which may not have been equally accessible for all locations included in this analysis. The number of registries in particular regions of the world also varies significantly. A region with a low number of registries may be less likely to accurately represent the true incidence in that area.

Conclusions

Our results revealed a significant difference in the AAIRs of malignant brain and other CNS tumors globally. Each histology category varied significantly between regions and different age groups. Although environmental risk factors may vary regionally, this would not be enough to explain the large differences in CNS tumor incidence observed between regions across the world, particularly between Asian countries and European and North American countries. Because this difference persisted in Asians living in the US and the UK, and is consistent with past studies, we believe that this indicates the importance of comparing genome-wide association studies in Asian-ancestry populations with European-ancestry populations. As CNS tumors are multifactorial, future studies comparing regional lifestyle and environmental risk factors, as well as genetic risk factors, should help to elucidate tumor etiology of this devastating disease.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Neuro-Oncology online.

Funding

Funding for CBTRUS was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under Contract No. 2016-M-9030, The Sontag Foundation, Genentech, Novocure, Celldex, AbbVie, along with the Musella Foundation, Voices Against Cancer, and the Zelda Dorin Tetenbaum Memorial Fund, as well as private and in-kind donations. Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the CDC.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was previously presented at the Society for Neuro-Oncology 2016 Annual Meeting in Scottsdale, Arizona.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(Suppl 4):iv1–iv62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kleihues P, Cavenee W, eds. Tumours of the nervous system: World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Louis DN, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum Heidelberg., International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization., ebrary Inc WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. World Health Organization classification of tumours. 4th ed Geneva, Switzerland: Distributed by WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(7):896–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL, Wrensch M, Black PM. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(6):1088–95; discussion 1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] 2013; http://globocan.iarc.fr.

- 8. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. X (electronic version) International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013; http://ci5.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Counsell CE, Grant R. Incidence studies of primary and secondary intracranial tumors: a systematic review of their methodology and results. J Neurooncol. 1998;37(3):241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Robles P, Fiest KM, Frolkis AD et al. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of primary brain tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(6):776–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fritz APC, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Perkin DM, Whelan S, ed. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat software version 8.3.4 2017; www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat.

- 13. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing 2017; http://www.R-project.org/.

- 14. Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15(6):547–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fay MP. asht: Applied Statistical Hypothesis Tests. R package version 0.6 2016; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=asht.

- 16. Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis 2009; http://had.co.nz/ggplot2/book.

- 17. Bivand R, Lewin-Koh N. maptools: Tools for Reading and Handling Spatial Objects. R package version 0.8–36 2015; http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maptools.

- 18. Bivand R, Keitt T, Rowlingson B. rgdal: Bindings for the Geospatial Data Abstraction Library. R package version 1.0–4 2015; http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgdal.

- 19. Bivand R, Rundel C. rgeos: Interface to Geometry Engine - Open Source (GEOS). R package version 0.3–11 2015; http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgeos.

- 20. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miranda-Filho A, Piñeros M, Soerjomataram I, Deltour I, Bray F. Cancers of the brain and CNS: global patterns and trends in incidence. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(2):270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crocetti E, Trama A, Stiller C et al. ; RARECARE working group. Epidemiology of glial and non-glial brain tumours in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(10):1532–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curado MP, Voti L, Sortino-Rachou AM. Cancer registration data and quality indicators in low and middle income countries: their interpretation and potential use for the improvement of cancer care. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(5):751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(7):896–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Linet MS, Slovis TL, Miller DL et al. Cancer risks associated with external radiation from diagnostic imaging procedures. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(2):75–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Turner MC, Krewski D, Armstrong BK et al. Allergy and brain tumors in the INTERPHONE study: pooled results from Australia, Canada, France, Israel, and New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(5):949–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai CK, Beasley R, Crane J, Foliaki S, Shah J, Weiland S; International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Three Study Group Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax. 2009;64(6):476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Vocht F, Hannam K, Buchan I. Environmental risk factors for cancers of the brain and nervous system: the use of ecological data to generate hypotheses. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70(5):349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. GLOBOCAN (2012) v1.0, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC cancerbase no. 11 (Internet). (database on the Internet) International Agency for Research on Cancer 2013; Available from http://globocan.iarc.fr. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chien LN, Gittleman H, Ostrom QT et al. Comparative brain and central nervous system tumor incidence and survival between the United States and Taiwan based on population-based registry. Front Public Health. 2016;4:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Cancer Intelligence Network and Cancer Research. Cancer Incidence and Survival Major Ethnic Group, England 2002–2006. London: National Cancer Intelligence Network and Cancer Research (2009) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dumitrescu L, Ritchie MD, Brown-Gentry K et al. Assessing the accuracy of observer-reported ancestry in a biorepository linked to electronic medical records. Genet Med. 2010;12(10):648–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shete S, Hosking FJ, Robertson LB et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Genet. 2009;41(8):899–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wrensch M, Jenkins RB, Chang JS et al. Variants in the CDKN2B and RTEL1 regions are associated with high-grade glioma susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41(8):905–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Walsh KM, Rice T, Decker PA et al. Genetic variants in telomerase-related genes are associated with an older age at diagnosis in glioma patients: evidence for distinct pathways of gliomagenesis. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(8):1041–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Enciso-Mora V, Hosking FJ, Di Stefano AL et al. Low penetrance susceptibility to glioma is caused by the TP53 variant rs78378222. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2178–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rajaraman P, Melin BS, Wang Z et al. Genome-wide association study of glioma and meta-analysis. Hum Genet. 2012;131(12):1877–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kinnersley B, Labussière M, Holroyd A et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu HB, Peng YP, Dou CW et al. Comprehensive study on associations between nine SNPs and glioma risk. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(10):4905–4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Song X, Zhou K, Zhao Y et al. Fine mapping analysis of a region of 20q13.33 identified five independent susceptibility loci for glioma in a Chinese Han population. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(5):1065–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li G, Jin T, Liang H et al. RTEL1 tagging SNPs and haplotypes were associated with glioma development. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van den Bent MJ. Interobserver variation of the histopathological diagnosis in clinical trials on glioma: a clinician’s perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(3):297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aldape K, Simmons ML, Davis RL et al. Discrepancies in diagnoses of neuroepithelial neoplasms: the San Francisco bay area adult glioma study. Cancer. 2000;88(10):2342–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davis FG, Malmer BS, Aldape K et al. Issues of diagnostic review in brain tumor studies: from the Brain Tumor Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(3):484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. The new WHO classification of brain tumours. Brain Pathol. 1993;3(3):255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Louis D, Wiestler O, Cavanee W, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Louis DN OH, Wiestler OD, Cavanee WK, ed. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.