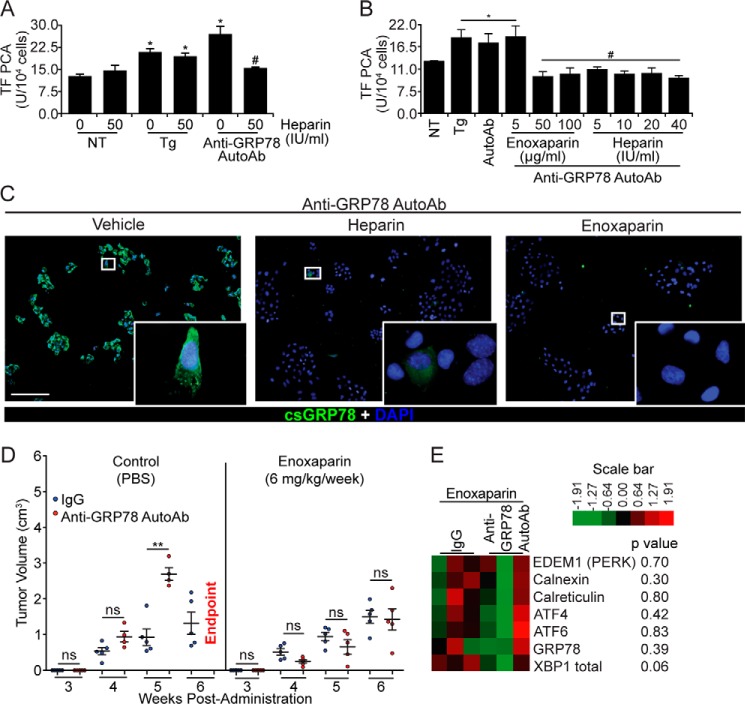

Figure 5.

Heparin and enoxaparin prevent the binding of anti-GRP78 AutoAbs to DU145 cells and inhibit tumor growth. A, heparin pretreatment (50 IU/ml) inhibits the effect of anti-GRP78 AutoAbs on TF activation, whereas it does not affect TF activity on non-treated (NT) or Tg-induced (5 μm) DU145 cells (*, p < 0.05 versus NT; #, p < 0.05 versus treatment with anti-GRP78 AutoAbs; n = 5/group). B, heparin (50–100 IU/ml) and enoxaparin (5–40 mg/ml) prevent anti-GRP78 AutoAb-mediated activation of TF in DU145 cells (*, p < 0.05 versus NT cells; #, p < 0.05 versus AutoAb treatment; n = 5/group). C, GRP78 binding and immunostaining (green) by anti-GRP78 AutoAbs on intact DU145 cells (left image) is abolished by pretreating cells with heparin (10 IU/ml; middle image) and enoxaparin (50 μg/ml; right image). DAPI was used to stain the nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. D, NOD/SCID mice bearing DU145 xenografts were treated with either anti-GRP78 AutoAbs (60 μg/ml) or human IgG (60 μg/ml, control), followed by a secondary treatment with either enoxaparin (6 mg/kg/week) or PBS (control). The observed potentiation of tumor growth by the anti-GRP78 AutoAbs (**, p < 0.001 versus IgG, n = 6/group, left) is abrogated by a secondary treatment with enoxaparin (n = 6/group, right). At week 6, all mice receiving anti-GRP78 AutoAb/PBS treatment reached the end point. ns, not significant. E, gene expression levels of seven UPR markers (derived by NanoString®) following treatment with control human IgG (60 μg/ml) or anti-GRP78 AutoAbs (60 μg/ml), followed by enoxaparin (6 mg/kg/week) treatment. p values are indicated for each gene; n = 3/treatment.