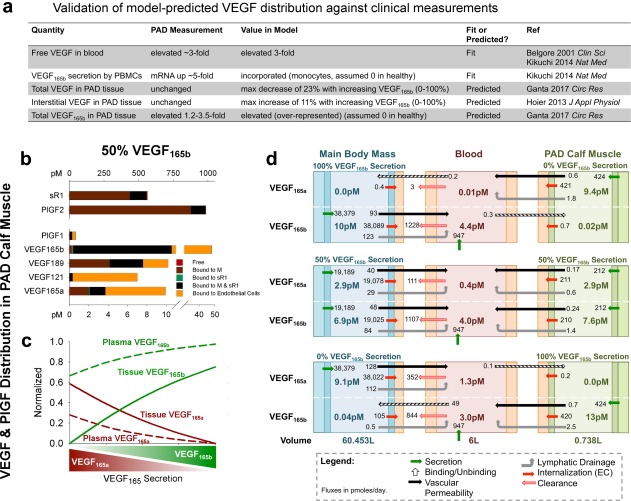

Figure 2.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)165b is predicted to be over‐represented in tissue and blood compared to VEGF165a. (a) Comparison of model‐predicted VEGF distribution to clinical measurements in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) vs. healthy control subjects. The VEGF splicing switch was modeled as a modification of the relative secretion rates of VEGF165a and VEGF165b, in agreement with measured changes in VEGF mRNA in PAD.25 (b) Predicted distribution of VEGF and placental growth factor (PlGF) isoforms and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (sVEGFR)1 in the PAD calf muscle, with equal secretion of VEGF165a and VEGF165b by parenchymal cells. Bound to M: ligand bound to extracellular matrix or basement membrane; bound to sVEGFR1: ligand bound to soluble VEGFR1 alone; bound to M and sVEGFR1: ligand bound to both matrix protein and soluble VEGFR1. (c) Fraction of total VEGF in plasma and PAD calf muscle (tissue) that is VEGF165a and VEGF165b, as a function of varying VEGF165 splicing (in both tissue compartments). (d) Steady‐state net flow profiles for VEGF165a and VEGF165b between the PAD calf muscle, blood, and main body mass, with different relative secretion of VEGF165a and VEGF165b in the PAD calf muscle and main body mass. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.