Conspectus

Human α-defensin 6 (HD6) is a 32-residue cysteine-rich peptide that contributes to innate immunity by protecting the host at mucosal sites. This peptide is produced in small intestinal Paneth cells as an 81-residue precursor peptide that is stored in granules, and is released into the lumen. One unusual feature of HD6 is that it lacks the broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity observed for other human α-defensins. HD6 exhibits unprecedented self-assembly properties, which confer an unusual host-defense function. HD6 monomers self-assemble into higher-order oligomers termed “nanonets,” which entrap microbes and prevent invasive pathogens from entering host cells. One possible advantage of this host-defense mechanism is that HD6 helps to keep microbes in the lumen where they can be killed or removed by other components of the immune system, such as recruited neutrophils, or excreted.

In this Account, we report our current understanding of HD6 and focus on work published since 2012 when Bevins and co-workers first described HD6 nanonets in the literature. First, we present studies that address the biosynthesis, storage and maturation of HD6, which demonstrate that Nature uses a propeptide strategy to spatially and temporally control the formation of HD6 nanonets in the small intestine. We subsequently highlight structure-function studies that provide a foundation for understanding the molecular basis for why HD6 exhibits unprecedented self-assembly properties compared to other characterized defensins. Lastly, we consider functional studies that illuminate how HD6 contributes to the mucosal immunity. In addition to blocking bacterial invasion into host epithelial cells, we recently discovered that HD6 suppresses virulence traits displayed by the opportunistic human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. In particular, we found that HD6 inhibits C. albicans biofilm formation, which causes complications in the treatment of candidiasis. We intend for this Account to inspire further biochemical, biophysical, and biological investigations that will advance our understanding of HD6 in mucosal immunity and the host-microbe interaction.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Host-defense peptides are abundant components of the innate immune system, which provides the first line of defense against microbial pathogens and helps maintain homeostatic balance between the host and its resident or commensal microbes.1 These peptides are deployed by the host at mucosal surfaces and at sites of infection.2,3 Defensins constitute an important class of host-defense peptide that are produced and utilized by lower and higher eukaryotes, including humans.4 Since the discovery of defensins several decades ago, many investigations have examined structure-function relationships and the roles of these peptides in the host-pathogen interaction.5–18

Defensins are small (2–5 kDa) cysteine-rich host-defense peptides expressed by epithelial cells and immune cells.4 In mammals, defensins exhibit three conserved and regiospecific intramolecular disulfide bonds in the oxidized or disulfide-linked forms (Figure 1). The disulfide bonds stabilize a three-stranded β-sheet fold and confer protease resistance.19–22 The specific disulfide-bond patterns divide the majority of mammalian defensins into two subclasses termed α- and β-defensins. The α-defensins exhibit CysI—CysVI, CysII—CysIV, CysIII—CysV linkages in the oxidized forms, whereas β-defensins have CysI—CysV, CysII—CysIV, CysIII—CysVI disulfide-bond patterns. The numbering scheme indicates the relative position of the Cys residues in the primary sequence starting from the N-terminus. θ-defensins compose a third subclass of defensins, which were first isolated from rhesus monkeys.15,23 Genes encoding θ-defensins are found in humans; however, these genes have premature stop codons, which prevent translation of the precursor peptide, and consequently humans produce only α- and β-defensins.18

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence of HD6 (top) and crystal structure (bottom) of the monomer. The numbers represent amino acid position. The cysteine residues in red compose the Cys4—Cys31, Cys6—Cys20, and Cys10—Cys30 disulfide linkages (black lines). The salt-bridge between Arg7 and Glu14 is indicated as a dashed line. The secondary structure depiction is based on the crystal structure shown below (PDB: 1ZMQ19) illustrating the three-stranded β-sheet fold of the HD6 monomer. In the monomer structure, the disulfide bonds are shown in yellow.

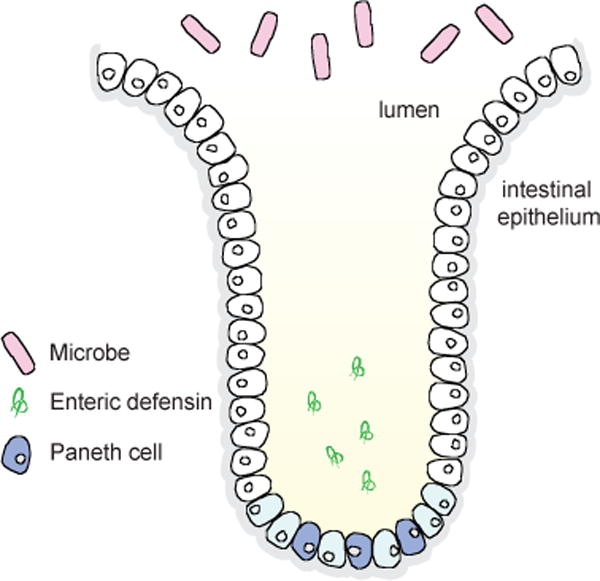

Humans produce six α-defensins named human neutrophil peptides 1–4 (HNP1–4) and human enteric defensins 5 and 6 (HD5 and HD6) (Figures 1 and 2).24 HNP1–4 are stored in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils,6,7 human monocytes,25 and natural killer cells.26 HD5 and HD6 are abundant in the granules of Paneth cells,8,27–29 secretory cells located at the bases of the crypts of Lieberkühn in the small intestine (Figure 3).30,31 Paneth cells package a cocktail of antimicrobial peptides and proteins in granules and release this mixture into the lumen to protect the intestinal epithelium from opportunistic and pathogenic microbes.31–33 Release of these host-defense factors is also considered to be important for intestinal homeostasis.33

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the six human α-defensins. The cysteine residues are colored red and the red lines represent the conserved disulfide linkages.

Figure 3.

Cartoon depiction of a small intestinal crypt illustrating the location and abundance of Paneth cells and the release of enteric α-defensins HD5 and HD6 into the lumen.

Most α-defensins exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity,3,18,34,35 and early studies revealed that defensins disrupt bacterial cell membranes. These observations, at least in part, afforded a generalized model whereby membrane destabilization results in bacterial cell death.4 In recent years, this model has been questioned to some degree because further investigations of select defensins illuminated alterative modes or multiple modes of action.36–40 Despite several conserved structural features, including the disulfide bonds and tertiary structure, the primary sequences of defensins are variable within a subclass. The different amino acid sequences afford variable net charge and hydrophobicity, and such diversity at the amino acid level can afford different biophysical and functional properties. For α-defensins, a comparison of HD5 and HD6 exemplifies this notion because HD5 exhibits broad-spectrum microbiocidal activity whereas HD6, at least in the oxidized form, exhibits negligible cell killing ability.19,22,35,38,41

Indeed, the functional role of HD6 was enigmatic for many years because no convincing antimicrobial activity could be identified during in vitro studies. In 2012, Bevins and co-workers reported seminal work using an HD6 transgenic mouse, which demonstrated that the peptide provides defense against the Gram-negative gastrointestinal pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) by an unprecedented mechanism.38 Rather than killing S. Typhimurium, the researchers found that HD6 oligomerizes into extended structures described as “nanonets” that entrap the bacteria in the intestinal lumen and thereby prevent bacterial invasion of the host epithelium and subsequent dissemination to other organs.38 Evidence for higher-ordered HD6 oligomers was observed in vivo (Figure 4) and further supported by in vitro studies. Although this behavior has not been found for other characterized defensins, the mechanism of bacterial entrapment is reminiscent of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which form when neutrophils release chromatin and thereby create an extracellular web-like structure that entangles invading microbes.42

Figure 4.

Scanning electron micrographs of wild-type (left) and HD6 transgenic (right) mouse ileal loop directly inoculated with S. Typhimurium.38 The rod-shaped objects are S. Typhimurium. A web-like structure in the HD6 transgenic mouse image, which is not observed in the wild-type mouse image, provides in vivo evidence for the formation of HD6 nanonets. The detailed molecular composition of this web-like structure is unknown. Scale bar = 2 µm. Copyright 2012 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Our laboratory initiated studies of the two human Paneth cell defensins in 2009. A significant portion of our research focuses on transition metal homeostasis and the host-microbe interaction, and our initial interest in HD5 and HD6 originated from our fascination with a labile zinc store of unknown function that is contained in Paneth cell granules.43–45 Although we remain interested in Paneth cell zinc, the report of HD6 nanonets fascinated us and motivated us to ask other questions. How do Paneth cell granules package HD6? When and how to the nanonets form? What are additional contributions of HD6 to mucosal immunity? In this Account, we present recent advances in our understanding of HD6 with focus on the biophysical and functional properties of this host-defense peptide. We highlight studies that afforded a model for HD6 storage and maturation,46 the molecular basis for oligomerization,22,38 and explorations of functional activity at the host/microbe interface.22,38,47 We intend for this synopsis to provide an introduction for the broad chemical community and newcomers to the field, and inspire future chemical and biological investigations of this remarkable self-assembling host defense peptide.

HD6 Storage and Maturation

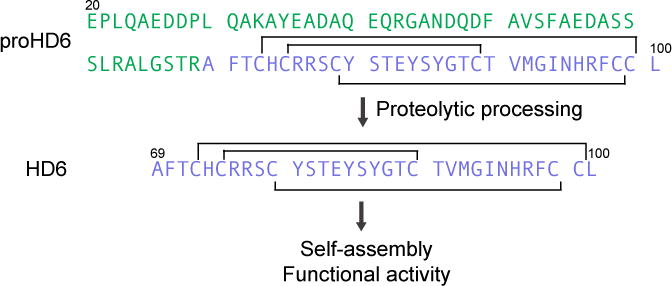

In collaboration with the Bevins laboratory, we recently elucidated critical steps in the maturation pathway of HD6.46 Because we had difficulty imaging that a Paneth cell granule packages and releases a micron-sized nanonet upon microbial stimuli, we hypothesized that HD6 is stored in the Paneth cell granules as an inactive form, and that oligomerization to create nanonets occurs during or following release into the lumen. Defensins are biosynthesized as prepropeptides containing a signal sequence for the secretory pathway (“pre” region), an N-terminal “pro” domain, and a C-terminal region that corresponds to the mature peptide (i.e. 32-aa HD6). Prior mRNA studies indicated that HD6 is translated as a 100-residue prepropeptide consisting of a 19-residue signaling sequence, a 49-residue pro region, and the C-terminal 32-residue mature HD6.27 Moreover, on the basis of the deduced amino acid sequence of proHD6, we identified trypsin as a candidate host protease for cleavage of proHD6 at the C-terminal end of Arg68 to release mature HD6 (Figure 5). In addition to entering the intestinal lumen following pancreatic release of trypsinogen, trypsin is expressed by human Paneth cells, and is reported to be the processing enzyme for HD5 maturation.48,49

Figure 5.

Amino acid sequences of proHD6 and HD6, and proposed maturation pathway. The pro region is in green, the sequence of mature HD6 is in purple, and the disulfide linkages are depicted as black lines.

We therefore proposed and tested a model where HD6 is stored as a propeptide (proHD6), and the N-terminal proregion prohibits self-assembly until it is cleaved by trypsin.46 Our ex vivo analyses of human intestinal tissues and luminal fluid provided several key insights that support this model. Only the oxidized form of proHD6 (81-aa) could be detected in samples of intestinal tissue, whereas only the mature oxidized peptide (32-aa) could be detected in the luminal fluid. Moreover, immunogold labeling transmission electron microscopy studies confirmed that HD6 is co-packaged with HD5 and trypsin in the secretory granules of Paneth cells. In vitro enzymatic activity assays performed with recombinant proHD6 established that this peptide is a substrate for trypsin, and trypsin-catalyzed hydrolysis releases HD6. Biophysical and functional evaluation of proHD6 revealed that the propeptide lacks the functional properties of HD6. In particular, proHD6 neither self-assembles into large oligomers nor causes bacterial agglutination nor prevents microbial invasion into human epithelial cells. Trypsin cleavage of the propeptide triggers HD6 self-assembly and functional activity. For instance, bacterial agglutination only occurs following cleavage of proHD6 (Figure 6). In summary, our investigations of HD6 maturation indicate that Paneth cells store the peptide as an inactive propeptide in granules. We reason that either during or after release into the lumen, proHD6 is cleaved by trypsin to generate HD6, the mature 32-residue form found in the intestinal lumen, thereby unleashing innate immune function.

Figure 6.

TEM analysis of HD6 self-assembly and SEM analysis of bacterial agglutination.46 Top row: transmission electron micrographs of 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4 (control), 0.4 µM trypsin (control), 20 µM proHD6 in the absence and presence of 0.4 µM trypsin, and 20 µM HD6. All the samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Scale bar = 100 nm. Middle row: scanning electron micrographs of E. coli ATCC 25922 treated with 50 mM Tris-maleate pH 6.4 (control), 0.4 µM APMSF-inactivated trypsin (control), 3 µM proHD6, 3 µM trypsin-cleaved proHD6, or 3 µM HD6. Scale bar = 20 µm. Bottom row: SEM of L. monocytogenes ATCC19115 treated under the same conditions as in the middle row. Scale bar = 20 µm. Copyright 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Several unanswered questions regarding proHD6 remain. The structure of proHD6 and the molecular basis for how the N-terminal pro region inhibits self-assembly warrant further investigation. Moreover, the pro regions of defensins exhibit different primary sequences, and whether these pro regions contain a molecular code relevant to defensin storage and maturation is unclear. Studies of the proteolytic processing and maturation of α-defensins demonstrated that the maturation pathways and proteases involved vary from peptide to peptide.46,48,50–53 Some defensins are packaged as propeptides whereas others are stored in the mature forms, and both of these packaging strategies occur for human α-defensins. HD5 and HD6 are stored in Paneth cell granules as propeptides,46,48,54 whereas the HNPs are stored in neutrophil granules as the mature peptides.5,55,56 Curiously, the HD5 propeptide is cationic (pI ≈ 9.5) whereas the HD6 and HNP propeptides are anionic (pI ≈ 4.5 for HD6; pI ≈ 5.5 for HNPs). These comparisons indicate that the amino acid sequence and net charge of the propeptide region are not reliable indicators of whether a particular propeptide will be processed before or after being packaged into granules, at least based on current observations. Lastly, although we have implicated trypsin as the processing enzyme for proHD6, we cannot rule out the possibility that this peptide is a substrate for another as-yet unidentified protease. Along these lines, we note that differences in the proteolytic processing of HD5 and HD6 appear to occur in vivo. Prior studies reported that several different isoforms of HD5 could be detected in human ileal fluid.48 These isoforms presumably result from protease-catalyzed hydrolysis at different positions within the pro region of proHD5, and all of these species displayed antibacterial activity.48 In contrast, only the 32-residue mature form of HD6 was detected in ileal fluid.46 Nature has therefore employed various strategies for defensin maturation even within a particular subclass for reasons that remain unknown and hence warrant further exploration.

HD6 Self-Assembly

The model of HD6 contributing to host defense by forming nanonets has motivated two investigations of the molecular basis of its self-assembly and ability to entrap microbes.22,38 A H27W variant of HD6 was first shown to have defective oligomerization properties.38 This observation afforded a proposal whereby electrostatic interactions between the imidazole ring of His27 and the C-terminal carboxyl group of Leu32 mediate HD6 self-assembly.38 Subsequent studies by our laboratory demonstrated that the H27A variant retained the ability to form higher-order oligomers and displayed functional activity, although transmission electron microscopy revealed that the H27A fibrils exhibit different morphology than the fibrils formed by HD6 (Figure 7).22 Taken together, these observations suggest that the attenuated self-assembly observed for the H27W variant is a consequence of the bulky tryptophan sidechain, and that His27 is not required for HD6 to form higher-order oligomers in aqueous buffer.

Figure 7.

Transmission electron micrographs of 20 µM HD6 and variants (10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4).22 Scale bar = 200 nm. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

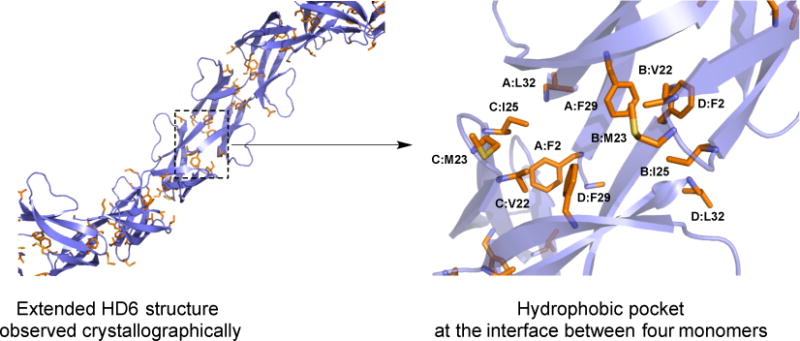

A comparison of the primary sequences of HD6 and other human α-defensins (Figure 2) and a reported crystal structure of HD619 (Figures 1 and 8) suggested the importance of hydrophobic residues for HD6 self-assembly.22 The positioning of hydrophobic residues in the HD6 primary sequence occurs largely in the loop between β2 and β 3 at the N- and C-termini of the peptide, which differs from the placement of hydrophobic residues in HD5 and the HNPs (Figure 2).22 Whereas most α-defensins crystallographically characterized to date have crystallized as dimers, the crystal structure of HD6 revealed that a hydrophobic pocket forms between four HD6 monomers, and these tetramers associate in a fibril-like chain (Figure 8).19,22 In the hydrophobic pocket, two monomers each contribute Phe2, Phe29 and Leu32, and the other two monomers each contribute Val22, Met23, and Ile25. Thus, in a structure-function study, we evaluated biophysical and function properties of four HD6 variants where Phe2, Val22, Ile25 and Phe29 were mutated.22 We observed that Phe2 and Phe29 are essential for both HD6 self-assembly and biological function. For example, mutation of either Phe2 or Phe29 to Ala (F2A and F29A variants, respectively) inhibits the self-assembly of HD6, leading to the absence of the elongated features observed by TEM (Figure 7). This conclusion was further supported by analytical ultracentrifugation, which demonstrated that the F2A and F29A variants predominantly exists as a monomers and dimers, respectively, in aqueous buffer at neutral pH.

Figure 8.

Extended crystal structure of HD6 (PDB: 1ZMQ19) and a close-up view of the hydrophobic pocket. Hydrophobic residues are shown in orange. Individual HD6 monomers are labeled A–D.

Our work established that HD6 forms higher-ordered structures in aqueous buffer and in the absence of bacteria or other biomolecules. This behavior differs from what was predicted from studies of wild-type and mutant S. Typhimurium treated with HD6, which indicated that certain cell surface proteins (i.e. flagellin) contribute to formation of HD6 nanonets and suggested that a nucleation site is needed.38 We reason that these observations are not mutually exclusive, and expect that further biophysical studies of HD6 structure and oligomerization (vide infra) will illuminate various factors that influence HD6 oligomerization.

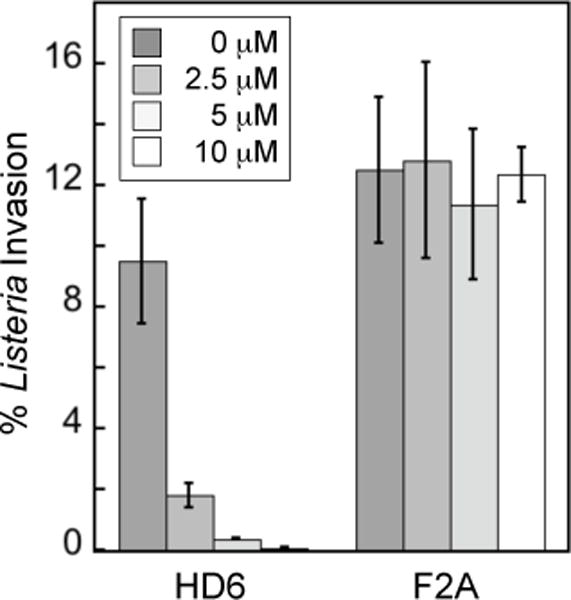

HD6 Blocks Bacterial Invasion into Host Cells

HD6 was first shown to entrap two Gram-negative bacterial pathogens of the gastrointestinal tract, S. Typhimurium and Yersinia enterocolitica, and thereby block the ability of these microbes to invade mammalian cells.38 Subsequently, we reported that HD6 prevents epithelial cell invasion by the Gram-positive gastrointestinal pathogen Listeria monocytogenes.22 For instance, the presence of HD6 (≥2.5 µM) causes the percentage of Listeria invasion to decrease by ≈5-fold (Figure 9).22 Moreover, HD6 variants that cannot form large oligomers (e.g. F2A, F29A) are unable to block Listeria invasion, supporting the model where self-assembly is essential for microbial entrapment.22 These results suggest that the ability of HD6 to prevent bacterial invasion is broad-spectrum with no apparent selectivity for Gram-negative or Gram-positive bacteria, and no preference for a given bacterial invasion mechanism. Nevertheless, on the basis of additional experimental observations, the interactions between HD6 and various microbial strains likely require consideration on a case-by-case basis. Microscopic analysis of different bacterial strains treated with HD6 revealed strain-dependent nanonet structures and differences in the amount of nanonets wrapping around these microbes,46 and evidence for interactions between HD6 nanonets and certain cell surface proteins of S. Typhimurium was reported.38 Thus, although the end result of HD6-mediated microbial entrapment appears general, the details for how the process occurs may vary from microbe to microbe and reflect different molecular compositions of bacterial surfaces.

Figure 9.

Invasion of human T84 epithelial cells by L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115 in the presence of HD6 and the F2A variant (mean ± SDM, n = 3).22

HD6 Prevents Fungal Biofilm Formation

Our recent exploratory work investigating the interplay between HD6 and fungi expands the scope of HD6 host-defense function to include eukaryotic pathogens.47 We employed the opportunistic human pathogen Candida albicans in these studies. C. albicans is a part of the normal flora in healthy individuals and is usually confined to the skin and mucosal surfaces such as the gastrointestinal tract.57 Nevertheless, this microbe can cause superficial and systemic infections in certain individuals, including infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised hosts.58,59 C. albicans can invade into the host epithelium and subsequently disseminate, which can result in deleterious bloodstream infections.60 Moreover, this fungi forms biofilms on surfaces, including medical devices such as catheters, which causes enhanced resistance to antifungal drugs and limits treatment options.61 Based on the ability of HD6 to block bacterial invasion into host cells, we questioned whether the peptide also confers host-defense against C. albicans and other fungi by a similar mechanism. Moreover, inspired by a recent study reporting that mucins prevent biofilm formation by C. albicans,62 we questioned whether HD6 exhibits similar function. Our work revealed that HD6 suppresses two virulence traits of C. albicans, namely biofilm formation and cell invasion.47 Indeed, visual inspection of C. albicans cultured in the absence or presence of the peptide revealed that HD6 disrupts biofilm formation (Figure 10A). Quantitative analysis of the biofilm (Figure 10B) and the number of planktonic cells in the culture supernatants (Figure 10C) indicated that HD6 reduced the amount of biofilm formed in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. For example, 20 µM HD6 reduced the amount of biofilm by ≈4- and ≈5-fold compared to the untreated control after 24 and 48 h, respectively. In contrast, cultures treated with the F2A variant displayed the same amount of biofilm as the untreated control, indicating that the self-assembly of HD6 is essential for the inhibition of fungal biofilm formation.

Figure 10.

HD6 attenuates biofilm formation by C. albicans.47 (A) Macroscopic view of biofilms of C. albicans SC5314 grown in the presence of HD6 or the F2A variant. The well diameter is 15.6 mm. (B) The amount of C. albicans biofilm starting from the yeast state in the presence of HD6 or 20 µM F2A. In this assay, greater absorbance at 550 nm indicates greater biofilm formation. (C) The CFU/mL of C. albicans in the supernatant after treatment with HD6 or F2A, which provides a measure of planktonic cells. The quantification presented in panels C and D was performed for the same samples. An asterisk indicates that no colony was detected. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Thus, in addition to MUC5AC62 and other mucins,63,64 HD6 provides a new example of a microbe-binding biomolecule that suppresses microbial virulence.65 Employing these host-defense agents may be a general host-defense mechanism for keeping C. albicans and other opportunistic pathogens in a harmless, commensal state. In contrast to mucins, our work indicated that HD6 does not prevent the morphological transition of C. albicans from budding yeast to virulent hyphae. Mechanistic investigations into the interlay between HD6 and fungi is a topic for future work. Indeed, we hypothesized that HD6 may interact with certain fungal membrane proteins, such as adhesins, and thereby prevent these proteins from binding to hydrophobic surfaces and initiating biofilm formation.66,67 This putative mechanism is reminiscent to the studies reporting HD6 interactions with membrane proteins of S. Typhimurium.38

Summary and Perspectives

HD6 is a remarkable defensin peptide that has captured the host-defense peptide community’s interest in recent years because of its unprecedented self-assembly properties and innate immune function. Our investigations of HD6, presented in this Account, define critical steps in its maturation pathway, provide insight into why its self assembly properties differ from those of HD5 and other defensins, and support a model whereby the peptide contributes to the barrier function of the intestinal mucosa. Despite these recent advances, our fundamental understanding of HD6 remains in its infancy and there are many research avenues for future consideration.

From a molecular standpoint, structural elucidation of the HD6 self-assemblies observed by microscopy and how these structures respond to varying conditions and the presence of other biomolecules will afford important biophysical insights into HD6 oligomerization. Moreover, whether the nanonets are a thermodynamic sink or dynamic with HD6 monomers or small oligomers associating and dissociating from a larger assembly is unknown. Towards understanding the HD6-microbe interaction, further investigations of how HD6 associates with microbes, including both commensal organisms and human pathogens, and why the nanonet structures appear to be dependent on the bacterial strain by scanning electron microscopy are warranted.

From the standpoint of HD6 function in the intestine, many unanswered questions remain. Following release into the intestinal mucosa, HD6 encounters other host-defense factors performing variable functions to provide barrier function and protect the host from potentially harmful microbes. Because the vast majority of studies focus on one host-defense molecule and because of the difficulties in recapitulating the complex mucosal environment in vitro, we are faced with a paucity of information about the interplay between host-defense factors. We speculate that entrapment of bacterial pathogens by HD6 in the lumen not only prevents bacterial species that invade host cells from reaching this destination and causing infection, but also keeps these bacteria in the intestinal lumen to be killed by other host-defense factors, such as other Paneth cell antimicrobials and recruited neutrophils. Thus, ascertaining whether there are unappreciated synergies between HD6 and other biomolecules will fill a knowledge gap and may provide a clearer picture of how the innate immune system functions both in the response to microbial pathogens at mucosal sites and in intestinal homeostasis. Moreover, consideration of the function and fate of HD6 nanonets within pathophysiological contexts such as intestinal inflammation is warranted.

In closing, we are currently faced with a global public health problem of antibiotic resistant microbial infections. Fundamental understanding of the different strategies utilized by the immune system to counteract microbial challenge provides a foundation for new approaches to treating infectious disease. HD6 provides a novel example of how Nature uses self-assembly for a beneficial outcome. Nanonet formation from a 32-residue cysteine-rich peptide to capture pathogens is a remarkable strategy for protecting the host from the harm caused by microbial invaders. Along these lines, we reason that mimicking the HD6 host-defense strategy may provide a non-traditional therapeutic strategy to combat microbial infections in humans.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge NIH Grant DP2OD007045 for supporting our early work on human α-defensins. We thank Prof. C. L. Bevins and his laboratory for collaborating on studies of proHD6, and Dr. Toshiki Nakashige for preparing Figure 3. PC is a recipient of a Royal Thai Government Fellowship.

Biographies

Phoom Chairatana received his Ph.D. in Biological Chemistry from MIT in 2016. He is currently teaching in the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital (Mahidol University, Thailand), and he will begin a postdoctoral position in Professor D. Monack’s laboratory at Stanford University in September 2017.

Elizabeth M. Nolan is an Associate Professor of Chemistry at MIT. Her research group investigates human host-defense peptides and proteins, and the bioinorganic chemistry the host-microbe interaction and infectious disease.

References

- 1.Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799–809. doi: 10.1038/nri2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao L, Lu W. Defensins in innate immunity. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21:37–42. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz T. Defensins : antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–720. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice WG, Ganz T, Kinkade JM, Jr, Selsted ME, Lehrer RI, Parmley RT. Defensin-rich dense granules of human neutrophils. Blood. 1987;70:757–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabay JE, Scott RW, Campanelli D, Griffith J, Wilde C, Marra MN, Seeger M, Nathan CF. Antibiotic proteins of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5610–5614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilde C, Gabay JE, Marra MN, Snable JL, Scott RW. Purification and characterization of human neutrophil peptide 4, a novel member of the defensin family. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11200–11203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DE, Bevins CL. Paneth cells of the human small intestine express an antimicrobial peptide gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23216–23225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans EW, Beach GG, Wunderlich J, Harmon BG. Isolation of antimicrobial peptides from avian heterophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:661–665. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selsted ME, Tang Y-Q, Morris WL, McGuire PA, Novotny MJ, Smith W, Henschen AH, Cullor JS. Purification, primary structures, and antibacterial activities of β-defensins, a new family of antimicrobial peptides from bovine neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6641–6648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwig SSL, Swiderek KM, Kokryakov VN, Tan L, Lee TD, Panyutich EA, Aleshina GM, Shamova OV, Lehrer RI. Gallinacins: cysteine-rich antimicrobial peptides of chicken leukocytes. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouellette AJ, Hsieh MM, Nosek MT, Cano-Gauci DF, Huttner KM, Buick RN, Selsted ME. Mouse Paneth cell defensins: primary structures and antibacterial activities of numerous cryptdin isoforms. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5040–5047. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5040-5047.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broekaert WF, Terras FRG, Cammue BPA, Osborn RW. Plant defensins: novel antimicrobial peptides as components of the host defense system. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1353–1358. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Destoumieux D, Bulet P, Loew D, Van Dorsselaer A, Rodriguez J, Bachère E. Penaeidins, a new family of antimicrobial peptides isolated from the shrim Penaeus vannamei (decapoda) J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28398–28406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang Y-Q, Yuan J, Ösapay G, Ösapay K, Tran D, Miller CJ, Ouellette AJ, Selsted ME. A cyclic antimicrobial peptide produced in primate leukocytes by the ligation of two truncated α-defensins. Science. 1999;286:498–502. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehrer RI, Ganz T. Antimicrobial peptides in mammalian and insect host defence. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou J, Mercier C, Koussounadis A, Secombes C. Discovery of multiple beta-defensin like homologues in teleost fish. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehrer RI, Lu W. α-Defensins in human innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:84–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szyk A, Wu Z, Tucker K, Yang D, Lu W, Lubkowski J. Crystal structures of human α-defensins HNP4, HD5, and HD6. Prot Sci. 2006;15:2749–2760. doi: 10.1110/ps.062336606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maemoto A, Qu X, Rosengren KJ, Tanabe H, Henschen-Edman A, Craik DJ, Ouellette AJ. Functional analysis of the α-defensin disulfide array in mouse cryptdin-4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44188–44196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanniarachchi YA, Kaczmarek P, Wan A, Nolan EM. Human defensin 5 disulfide array mutants: disulfide bond deletion attenuates antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8005–8017. doi: 10.1021/bi201043j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chairatana P, Nolan EM. Molecular basis for self-assembly of a human host-defense peptide that entraps bacterial pathogens. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:13267–13276. doi: 10.1021/ja5057906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehrer RI, Cole AM, Selsted ME. θ-Defensins: cyclic peptides with endless potential. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27014–27019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.346098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Mammalian defensins in the antimicrobial immune response. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:551–557. doi: 10.1038/ni1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackewicz CE, Yuan J, Tran P, Diaz L, Mack E, Selsted ME, Levy JA. α-Defensins can have anti-HIV activity but are not CD8 cell anti-HIV factors. AIDS. 2003;17:F23–F32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalifour A, Jeannin P, Gauchat J-F, Blaecke A, Malissard M, N’Guyen T, Thieblemont N, Delneste Y. Direct bacterial protein PAMP recognition by human NK cells involves TLRs and triggers α-defensin production. Blood. 2004;104:1778–1783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DE, Bevins CL. Defensin-6 mRNA in human Paneth cells: implications for antimicrobial peptides in host defense of the human bowel. FEBS Lett. 1993;315:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallow EB, Harris A, Salzman N, Russell JP, DeBerardinis RJ, Ruchelli E, Bevins CL. Human enteric defensins: gene structure and developmental expression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4038–4045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter EM, Liu L, Oren A, Anton PA, Ganz T. Localization of human intestinal defensin 5 in Paneth cell granules. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2389–2395. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2389-2395.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter EM, Bevins CL, Ghosh D, Ganz T. The multifaceted Paneth cell. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:156–170. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8412-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clevers HC, Bevins CL. Paneth cells: maestros of the small intestinal crypts. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:289–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cells and innate mucosal immunity. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:547–553. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833dccde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bevins CL, Salzman NH. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:356–368. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cell α-defensins in enteric innate immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2215–2229. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0714-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ericksen B, Wu Z, Lu W, Lehrer RI. Antibacterial activity and specificity of the six human α-defensins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:269–275. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.269-275.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider T, Kruse T, Wimmer R, Wiedemann I, Sass V, Pag U, Jansen A, Nielsen AK, Mygind PH, Raventos DS, Neve S, Ravn B, Bonvin AMJJ, De Maria L, Andersen AS, Gammelgaard LK, Sahl H-G, Kristensen H-H. Plectasin, a Fungal Defensin, Targets the Bacterial Cell Wall Precursor Lipid II. Science. 2010;328:1168–1172. doi: 10.1126/science.1185723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Leeuw E, Li C, Zeng P, Li C, Diepeveen-de Buin M, Lu W-Y, Breukink E, Lu W. Functional Interaction of human neutrophil peptide-1 with the cell wall precursor lipid II. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1543–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu H, Pazgier M, Jung G, Nuccio S-P, Castillo PA, de Jong MF, Winter MG, Winter SE, Wehkamp J, Shen B, Salzman NH, Underwood MA, Tsolis RM, Young GM, Lu W, Lehrer RI, Bäumler AJ, Bevins CL. Human α-defensin 6 promotes mucosal innate immunity through self-assembled peptide nanonets. Science. 2012;337:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1218831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kudryashova E, Quintyn R, Seveau S, Lu W, Wysocki VH, Kudryashov DS. Human defensins facilitate local unfolding of thermodynamically unstable regions of bacterial protein toxins. Immunity. 2014;41:709–721. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moser S, Chileveru HR, Tomaras J, Nolan EM. A bacterial mutant library as a tool to study the attack of a defensin peptide. Chembiochem. 2014;15:2684–2688. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder BO, Ehmann D, Precht JC, Castillo PA, Küchler R, Berger J, Schaller M, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Paneth cell α-defensin 6 (HD-6) is an antimicrobial peptide. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:661–671. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dinsdale D. Ultrastructural localization of zinc and calcium within the granules of rat Paneth cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1984;32:139–145. doi: 10.1177/32.2.6693753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelly P, Feakins R, Domizio P, Murphy J, Bevins C, Wilson J, McPhail G, Poulsom R, Dhaliwal W. Paneth cell granule depletion in the human small intestine under infective and nutritional stress. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giblin LJ, Chang CJ, Bentley AF, Frederickson C, Lippard SJ, Frederickson CJ. Zinc-secreting Paneth cells studied by ZP fluorescence. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:311–316. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6724.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chairatana P, Chu H, Castillo PA, Shen B, Bevins CL, Nolan EM. Proteolysis triggers self-assembly and unmasks innate immune function of a human α-defensin peptide. Chem Sci. 2016;7:1738–1752. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chairatana P, Chiang IL, Nolan EM. Human a-defensin 6 self-assembly prevents adhesion and suppresses virulence traits of Candida albicans. Biochemistry. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01111. Just Accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh D, Porter E, Shen B, Lee SK, Wilk D, Drazba J, Yadav SP, Crabb JW, Ganz T, Bevins CL. Paneth cell trypsin is the processing enzyme for human defensin-5. Nature. 2002;3:583–590. doi: 10.1038/ni797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bohe M, Borgström A, Lindström C, Ohlsson K. Pancreatic endoproteases and pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor immunoreactivity in human Paneth cells. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:786–793. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.7.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glenthøj A, Glenthøj AJ, Borregaard N. ProHNPs are the principal α-defensins of human plasma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:836–843. doi: 10.1111/eci.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glenthøj A, Nickles K, Cowland J, Borregaard N. Processing of neutrophil α-defensins does not rely on serine protease. in vivo PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson CL, Ouellette AJ, Satchell DP, Ayabe T, López-Boado YS, Stratman JL, Hultgren SJ, Matrisian LM, Parks WC. Regulation of intestinal α-defensin activation by the metalloproteinase matrilysin in innate host defense. Science. 1999;286:113–117. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5437.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Pesendorfer P, Tanabe H, Wilson CL, Hagen SJ, Ouellette AJ. Activation of Paneth cell α-defensins in mouse small intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5219–5228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cunliffe RN, Rose FRAJ, Keyte J, Abberley L, Chan WC, Mahida YR. Human defensin 5 is stored in precursor form in normal Paneth cells and is expressed by some villous epithelial cells and by metaplastic Paneth cells in the colon in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48:176–185. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valore EV, Ganz T. Posttranslational processing of defensins in immature human myeloid cells. Blood. 1992;79:1538–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faurschou M, Sørensen OE, Johnsen AH, Askaa J, Borregaard N. Defensin-rich granules of human neutrophils: characterization of secretory properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1591:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martins N, Ferreira ICFR, Barros L, Silva S, Henriques M. Candidiasis: predisposing factors, prevention, diagnosis and alternative treatment. Mycopathologia. 2014;177:223–240. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sobel JD. Vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1896–1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sudbery PE. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:737–748. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dodd CL, Greenspan D, Katz MH, Westenhouse JL, Feigal DW, Greenspan JS. Oral candidiasis in HIV infection: pseudomembranous and erythematous candidiasis show similar rates of progression to AIDS. AIDS. 1991;5:1339–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamill RJ. Amphotericin B formulations: a comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs. 2013;73:919–934. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kavanaugh NL, Zhang AQ, Nobile CJ, Johnson AD, Ribbeck K. Mucins suppress virulence traits of Candida albicans. mBio. 2014;5:e01911–01914. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01911-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murciano C, Moyes DL, Runglall M, Tobouti P, Islam A, Hoyer LL, Naglik JR. Evaluation of the role of Candida albicans agglutinin-like sequence (Als) proteins in human oral epithelial cell interactions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogasawara A, Komaki N, Akai H, Hori K, Watanabe H, Watanabe T, Mikami T, Matsumoto T. Hyphal formation of Candida albicans is inhibited by salivary mucin. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:284–286. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chairatana P, Nolan EM. Defensins, lectins, mucins, and secretory immunoglobilin A: microbe-binding biomolecules that contribute to mucosal immunity in the human gut. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1080/10409238.2016.1243654. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phan QT, Myers CL, Fu Y, Sheppard DC, Yeaman MR, Welch WH, Ibrahim AS, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLOS Biol. 2007;5:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaffin WL. Candida albicans cell wall proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:495–544. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]