Abstract

One of the most popular procedures amongst obesity surgery is the sleeve gastrectomy. There is international consensus regarding the usage of bougie for sleeve gastrectomy calibration. Nevertheless, there is a dissociation between the number of oesophageal perforations reported for any other oesophageal/gastric operation that requires bougie (e.g., anti-reflux surgery, incidence 1.2%) and bariatric surgery, where this complication seems to be almost a myth. Interestingly enough, the number of bariatric procedures is much higher than any other oesophageal/gastric surgery. This suggests that oesophageal perforations in obesity surgery are underreported. We report a case of injury of the intrathoracic oesophagus with bougie that occurred during a sleeve gastrectomy. In the infrequent case that the perforation is diagnosed during surgery, primary repair during the same intervention is highly recommended. Videothoracoscopy might be an effective option in case of necessity. We were able to complete the sleeve gastrectomy without increasing morbidity.

Keywords: Bougie, oesophagus perforation, sleeve gastrectomy, videothoracoscopy

INTRODUCTION

One of the most popular procedures amongst obesity surgery is the sleeve gastrectomy. There is international consensus regarding the usage of bougie for sleeve gastrectomy calibration. Nevertheless, there is a dissociation between the number of oesophageal perforations reported for any other oesophageal/gastric operation that requires bougie (e.g., anti-reflux surgery, incidence 1.2%) and bariatric surgery, where this complication seems to be almost a myth. Interestingly enough, the number of bariatric procedures is much higher than any other oesophageal/gastric surgery. This suggests that oesophageal perforations in obesity surgery are underreported.

Herein, we report a case of injury of the intrathoracic oesophagus that occurred during a sleeve gastrectomy which was diagnosed intraoperatively. This is the first intraoperative diagnosed case that was also treated with a minimally invasive technique in our knowledge.

PROCEDURE

We present a 64-year-old female, with a body mass index (BMI) of 39 kg/m2. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and smoking habits.

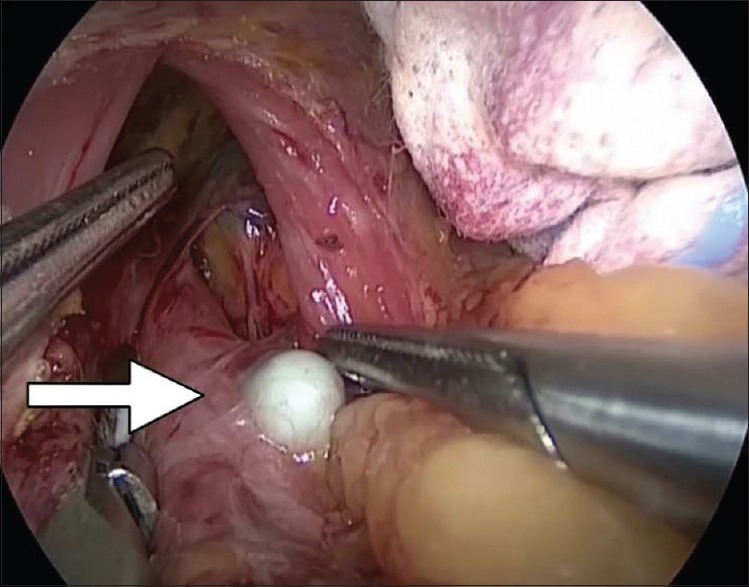

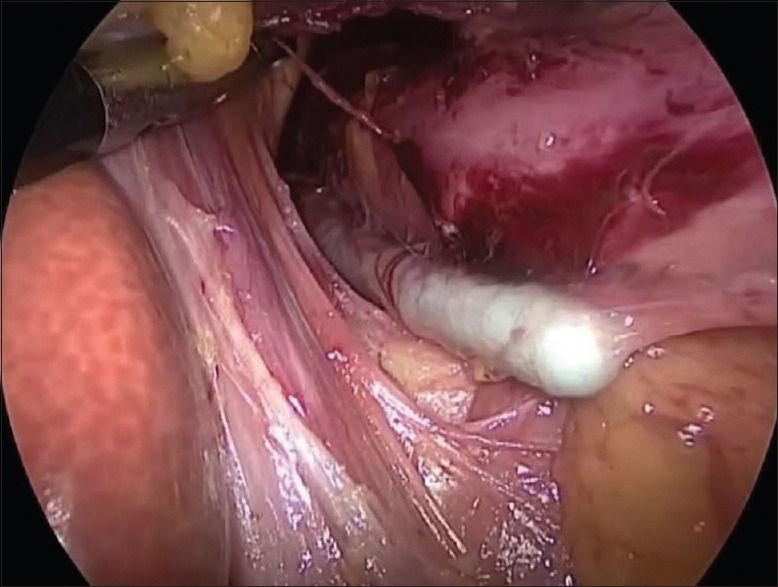

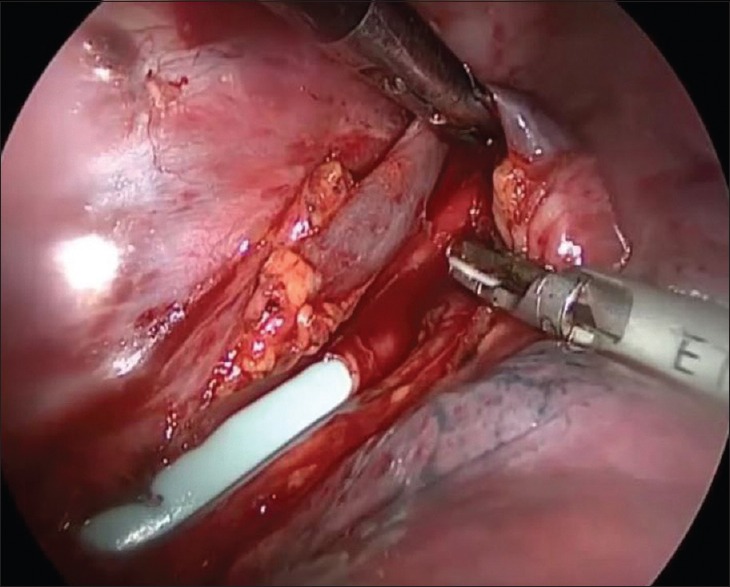

Decision was made to perform a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Unfortunately, an oesophageal perforation occurred during the insertion of the bougie for calibration. This unexpected event was diagnosed by observing the bougie coming through the phrenoesophageal ligament [Figure 1]. The crura were then dissected to gain access to the mediastinum, but the perforation could not be identified [Figure 2]. Videothoracoscopy was then decided. The patient was placed in a 45° left lateral decubitus position. The right lung was deflated to improve the access. Dissection was conducted using the Harmonic Scalpel® until the perforation was detected, below the arch of the azygos vein [Figure 3]. The lesion was about 3 cm long in its greater diameter. The azygos vein was transected using a 45 mm vascular stapler. The perforation was then repaired in two layers over a 42 French bougie, using 2.0 Vicryl running suture for the inner layer and interrupted stitches for the outer one. A pleural patch was used to reinforce the suture. Pneumohydraulic test was performed to rule out the presence of leaks. A chest tube was placed and wounds were closed.

Figure 1.

Bougie (arrow) coming through the phrenoesophageal ligament

Figure 2.

Dissection of the crura

Figure 3.

Perforation detected below the arch of the azygos vein

The patient was then returned to her original position, and the sleeve gastrectomy was completed without further complications. The crura were closed using 2.0 Ethibond interrupted stitches. Methylene blue test was performed confirming the absence of staple line leaks. Two drains were left, one along the staple line of the sleeve and the other one in the mediastinum, through the hiatus.

Operative time was 5 h and the patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) previous extubation. A nasogastric tube was left in place. No vasoactive drugs were needed.

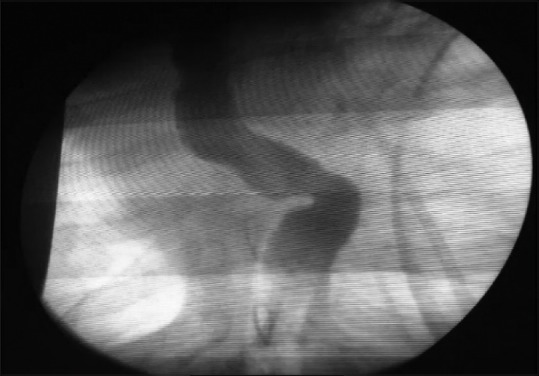

She spent 3 days in the ICU, and her chest tube was removed on post-operative day #3. A gastrografin swallow was done on post-operative day #4 showing no leaks. Interestingly, a significant oesophageal curvature was noticed, which might have been the ultimate cause of perforation [Figure 4]. She was started on liquids on post-operative day #5 and was discharged home on post-operative day #6. Another gastrografin swallow was performed 15 days from discharge which revealed no complications. At 2 years follow-up, her BMI was 30 kg/m2 and she did not have any further oesophageal complications.

Figure 4.

Gastrografin swallow on post-operative day #4 showing no leaks. A significant oesophageal curvature was noticed

DISCUSSION

Oesophageal perforations are a rare entity; however, they have been associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. A meta-analysis that included 75 studies and almost 3000 patients showed that iatrogenic perforation is the most common cause. This is our first oesophageal perforation in bariatric surgery with 140 cases per year operated during the past 6 years. So far, our oesophagical perforation rate is 0.1%. Mortality rate mainly varies according to localisation and time to treatment. Cervical oesophageal perforations tend to incite less systemic inflammatory response than thoracic and abdominal perforations, due to the containment of the contents within the fascial planes of the neck. Perforations occurring in this area are not as well contained, eliciting local and systemic inflammatory response. Lesions treated within the first 24 h have substantially better results than those treated after the 1st day with a 7.4% and 20.3% mortality rate, respectively.

Consequences following oesophageal perforation make this complication a prime litigation target. A study that took place in America analysed 59 lawsuits. Gastroenterologists, general surgeons and anaesthesiologists were the most commonly named defendants. In addition, only two-thirds of the defendants resulted acquitted, whereas 11.9% of cases were settled (median – $650,000); 20.3% resulted in awarded damages (median – $1.2 M). Necessity of surgical repair and delay in diagnosis were two of the most common factors present in litigated cases resulting in payment. This study concluded that oesophageal perforation should always be included within the complications list in the informed consent for abdominal surgery and that this should be emphasised in any patient at risk of intubation injury.

In high-volume centres for bariatric procedures, oesophageal perforation must always be considered as a differential diagnosis in those patients with abnormal post-operative course. Early diagnosis is critical since prognosis can dramatically change if it is made within the first 24 h of the perforation. Although gastrografin swallow is accessible and specific, it has low sensitivity, with 50% false-negative results. Computed tomography scan is the study of choice when diagnosing this type of complication. Finally, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy can serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool.

The therapeutic approach recommendation is changing over time. A number of competing treatment modalities ranging from conservative to surgical approaches are available for the management of this complication. Conservative treatment is indicated in those cases of small confined leaks where the patient is clinically stable. Endoscopic approach is useful in patients diagnosed within the 1st day who present localised collections. Currently, there are four possible endoscopic treatment options for this kind of lesions: stents, through the scope clips (TTSC), over the scope clips (OTSC) and endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT). Stents have shown success rates of 81% if they are used in conjunction with an additional drainage procedure. Stent migration rates were significantly higher with plastic (27%) than with metallic stents (11%) although metallic stents have significantly higher incidence of post-procedure strictures (3%). Nevertheless, when comparing both types of stents, there are no statistically significant differences in terms of effectiveness in the management of benign oesophageal perforations. This method is helpful in large perforations (2.5–3 cm). TTSC has great limitations in the treatment of oesophageal perforations due to their little wing span and the low compression force that these clips can apply. However, they can be considered as a complementary tool for other techniques such as stent fixation or to ultimate an OTSC closure. OTSC has overcome the limitations mentioned above. These are nitinol clips with a ‘bear claw’ shape that are loaded on the tip of the scope. Reported success rates for OTSC are as high as 92% in the management perforations no >2 cm, diagnosed within the first 24 h of the event. They are specially recommended for the treatment of early lesions or chronic fistulae of <2 cm in diameter and were included in the recommendations of the current position statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. EVT is a novel technique that is showing very good results especially for the treatment of large lesions complicated with periesophageal abscess. This procedure consists in inserting polyurethane sponges into the abscess cavity which is connected to the leak, followed by application of controlled continuous negative pressure. This method provides the key elements for leak closure: drainage of inflammatory fluids and induction of tissue granulation. This procedure can be performed under conscious sedation. Sponges should be changed periodically, every 3–7 days. Recent reports recommend this method for early large perforations with active leakage connected to an abscess cavity. These therapies are not mutually exclusive, offering the possibility of being combined to increase the success rate.

The latest development is an endoscopic suturing device (EndoCinch™, Bard) although it does not have a defined role yet. There are a few reports supporting the usage of this method showing good results in gastric perforations. In any case, these devices are not available in every hospital, and they are typically expensive. In addition, their use requires a certain level of experience of the endoscopist.

Definitively, the evidence reported in the literature is consistent: surgical intervention has to be as early and aggressive as possible in cases diagnosed after 24 h of the occurrence, where sepsis and contamination are present, especially if the injury is located in the chest or in the abdomen. The surgical procedure varies in each particular case and depends not only on the size and location of the injury but also on the patient's clinical status. Malignancy is an important risk and prognosis factor and its presence changes the approach. Decision will always be made based on the analysis of each particular case; unfortunately, there is no clear evidence that shows a trend towards better or worse results due to the great scenario variety. Surgical treatment options include simple drainage, closure of the defect and drainage, complete surgical defunctionalisation with cervical stoma or oesophagectomy.

Pursuing the objectification and standardisation of the practice, the Pittsburgh group created a severity score that gives specific punctuation to each risk factor. According to this, perforations are divided into three groups: <2 points, 3–5 points and >5 points. This group suggests surgical treatment for those patients with >5 points and think about surgery versus endoscopic treatment for the group in the middle. The lowest punctuation group could be treated conservatively or minimally invasive. This score has been recently validated by a multicentric international group who also concluded that those patients with a score higher than 7 have 10 times more chances of dying.

In our case, the perforation was evidenced intraoperatively when the bougie appeared through the phrenoesophageal ligament. However, in this case, the usage of a blunt tip bougie did not prevent this complication, as it can be seen in Figure 1. There is no much evidence in the literature about how to manage these cases since intraoperative diagnosis is rarely done. In spite of this and considering that early detection is key to reduce the chemical effects of the perforation, closing the defect within the same surgical procedure seems to be a reasonable approach. Our patient suffered from a proximal intrathoracic perforation of the oesophagus just below the arch of the azygos vein. Due to this, despite the team's large experience, we were not able to reach the defect from the abdomen. Videothoracoscopy was then our next option. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluation would have been a good option for diagnosis but was not available in this emergency situation in the operating room. In addition, surgical approach was considered safer to perform the closure due to the size of the injury.

After closing the oesophageal perforation, the debate was if we should proceed with the bariatric surgery or not. After analysing the pros and cons, we agreed that the sleeve gastrectomy is a fast and secure procedure if it is being performed by an expert team. Consequently, we decided to take the risk considering that it would not add any morbidity to the oesophageal healing process. Actually, we did not find any reports recommending what to do in these complex cases.

CONCLUSION

Oesophageal perforation is a rare complication but is has been associated with high mortality rates. Early diagnosis seems to be the key to success. Nowadays, effective endoscopic options are available offering a minimally invasive approach and less morbidity. In advanced cases, surgical approach is still the gold standard. In the infrequent case that the perforation is diagnosed during surgery, primary repair during the same intervention is highly recommended, using the same approach if possible. Nevertheless, videothoracoscopy might be an effective option in case of necessity. We were able to complete the sleeve gastrectomy without increasing morbidity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.