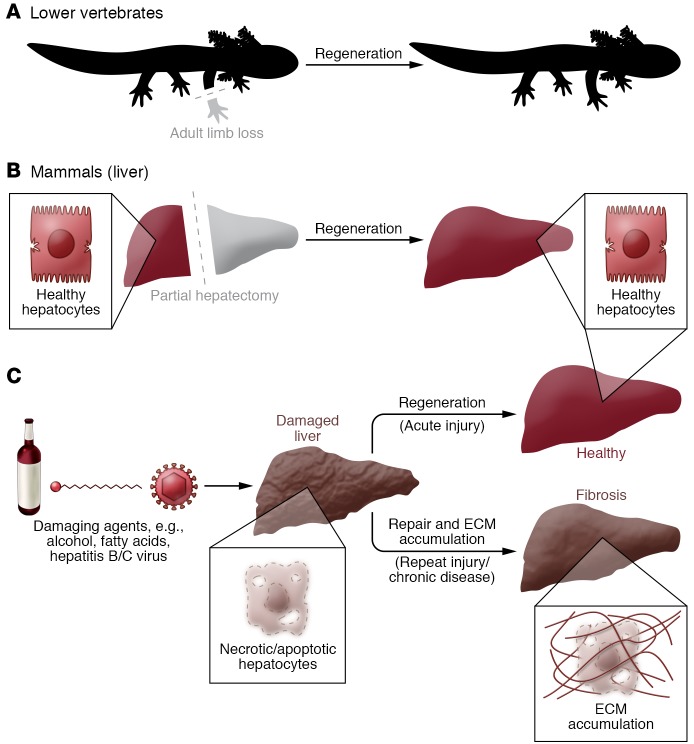

Figure 1. Coping with injury: regeneration versus repair.

(A) Lower vertebrates, such as axolotls, salamanders, and fish, are able to regenerate severed limbs through a process that reconstitutes original tissue anatomy and function without leaving a scar (a meshwork of ECM). Mammals may similarly regenerate complex tissues during embryogenesis, but lose most of this capacity in adulthood. (B) The liver is one of the few adult mammalian organs that retains a remarkable ability to regenerate itself. Resection of up to 70% of the liver mass via partial hepatectomy leads to compensatory growth from the intact tissue and fully restores organ size in a matter of days, similarly to axolotl limb regrowth. However, the hepatectomized liver is typically not injured or “damaged,” and regeneration is a result of the organ’s ability to sense insufficient size. (C) The liver may also regenerate following injury by exogenous and/or endogenous agents (e.g., alcohol, hepatitis B/C viruses, fatty acids) that cause hepatocyte death. This process is characterized by an inflammatory reaction and ECM synthesis/remodeling. However, if the damaging insult persists, the tissue will be repaired instead of regenerated, resulting in excessive scarring, known as fibrosis, that alters histoarchitecture and hinders optimal tissue function.