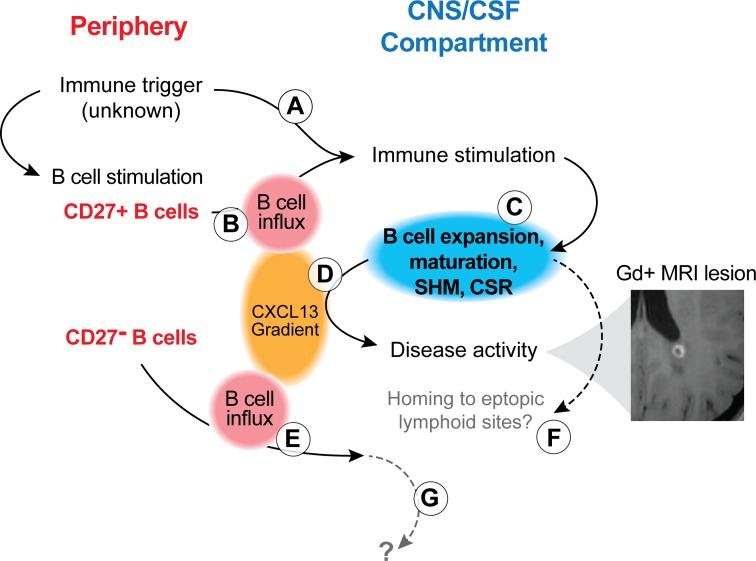

Figure 8. Model of B cell activation and involvement during MS disease activity.

Peripheral immune activation can lead to intrathecal immune stimulation, either via antigen nonspecific (A; e.g., via cytokines during an infectious disease) or antigen-specific (B; via preformed CD27+IgD– SM) mechanisms. This immune activation involves B and T cells, as supported by our flow cytometry findings and those of others (24) (Figures 1–3), and leads to B cell activation, modification of the B cell receptor (somatic hypermutation [SHM]; Ig-class switch recombination [CSR]) and B cell maturation (C). B cell influx and intrathecal B cell expansion are supported by Ig-RepSeq (Figures 5 and 6). These immune mechanisms support MS disease activity (evidenced by Gd+ MRI lesions; example from patient 57514) and lead to increased production of CXCL13 (D), which, in turn, also attracts CD27– B cells to the CNS/CSF compartment (E). These CD27– B cells may not have been involved in the initial peripheral immune triggering event; rather, their migration to the CNS could be a nonspecific event. Activated CD27+ B cells, once in the CNS, may further mature to antibody-secreting plasmablasts/plasma cells and may home to ectopic lymphoid sites (F). We found no evidence for CD27– IgD+ B cells maturing to antigen-specific CD27+ B cell subset; the fate of naive B cells in CSF remains unknown (G). It is important to note that several steps described in this model remain hypothetical and subject of future research.