Abstract

Mucormycosis is one of the most rapidly progressing and fulminant forms of fungal infection which usually begins in the nose and paranasal sinuses following inhalation of fungal spores. It is caused by organisms of the subphylum Mucormycotina, including genera as Absidia, Mucor, Rhizomucor, and Rhizopus. The incidence of mucormycosis is approximately 1.7 cases per 1,000,000 inhabitants per year. Mucormycosis affecting the maxilla is rare because of rich blood vessel supply of maxillofacial areas although more virulent fungi such as Mucor can overcome this difficulty. The common form of this infection is seen in the rhinomaxillary region and in patients with immunocompromised state such as diabetes. Hence, early diagnosis of this potentially life-threatening disease and prompt treatment is of prime importance in reducing the mortality rate.

Keywords: Diabetes, maxilla, mucormycosis, necrosis

Introduction

Mucormycosis (phycomycosis, zygomycosis) is a rare opportunistic fungal infection caused by fungi belonging to the Mucorales order and the Mucoraceae family. It was first described by Paultauf in 1885.[1] It represents the third most common angioinvasive fungal infection following candidiasis and aspergillosis.[2] It usually affects the immunocompromised individuals and is rarely seen in apparently healthy individuals.[3] In the compromised host, mucormycosis infection results from altered immunity in which rapid proliferation and invasion of fungal organisms ensue in deeper tissues.[4]

The various predisposing factors for mucormycosis are uncontrolled diabetes (particularly in patients having ketoacidosis), malignancies such as lymphomas and leukemias, renal failure, organ transplant, long-term corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy, cirrhosis, burns, protein-energy malnutrition, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).[5] Pathophysiology involves inhalation of spores through the nose or mouth or even through a skin laceration. Individuals with compromised cellular and humoral defense mechanisms may generate inadequate response. The fungus may then spread to the paranasal sinuses and consequently to the orbit, meninges, and brain by direct extension. However, some patients with mucormycosis have no identifiable risk factors.[6] Successful management of this fatal infection requires early identification of the disease and aggressive and prompt medical and surgical interventions to prevent the high morbidity and mortality associated with this disease process.[7] We report here with a case of mucormycosis of the maxilla in a diabetic patient.

Case Report

A 50-year-old female patient came to the outpatient department with a chief complaint of pain and swelling on her right side of the face for 4 months. The patient was apparently asymptomatic 4 months back and subsequently developed pain in the upper right posterior tooth region. The patient gave a history of dental extraction of the upper posterior tooth (both 15 and 16) previously, due to swelling and mobility 4 months back. Following the extraction, the socket had not healed, and then, she noticed denuded bone over the same area associated with nasal twang of voice. Her medical history revealed that she had uncontrolled diabetes for 4 months with fasting blood sugar level, 154 mg/dl (normal 70–110 mg/dl) and postlunch sugar level, 197 mg/dl (normal 70–140 mg/dl) and asthmatic for 5 years, and she was on medication for the same.

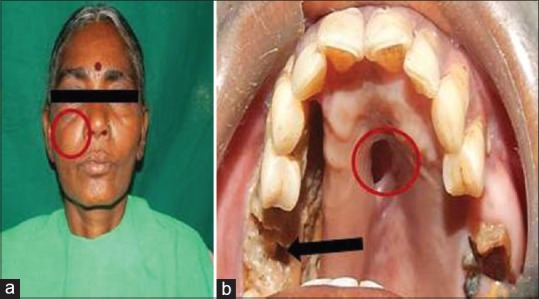

On extraoral examination, there was a mild diffuse swelling over the right middle third of the face which was extending mediolaterally from the lateral aspect of nose to the outer canthus of the eye and superoinferiorly from the infraorbital region to 1 cm above the corner of the mouth, respectively. The skin over the swelling was normal with blackish pigmentation near infraorbital region. On palpation, the swelling was soft in consistency, tender with no local rise of temperature [Figure 1a]. The lymph nodes were not palpable. A small swelling of size 1 cm in diameter is seen in relation to the medial aspect of bridge of the nose. Nasal twang of voice is also noted. Eye movements were normal, and pupils were reactive. Paraesthesia over right side infraorbital region with circumorbital edema over the right eye was noted. The facial expressions were normal.

Figure 1.

(a) Extraoral photograph showing diffuse swelling on the right middle third of the face (red circle). (b) Intraoral photograph showing necrotic bone (black arrow) and oroantral communication in the palate (red circle)

Intraoral examination revealed missing tooth in relation to 15, 16. Denuded mucosa with exposed necrotic gray-colored bone was seen from mesial aspect of 13 to distal aspect of 17 extending buccally and palatally involving the alveolar ridge in region of 15 and 16. The surrounding mucosa was normal with an oroantral communication in the mid palatine region was seen [Figure 1b]. On palpation, the affected area was rough in texture with mild tenderness.

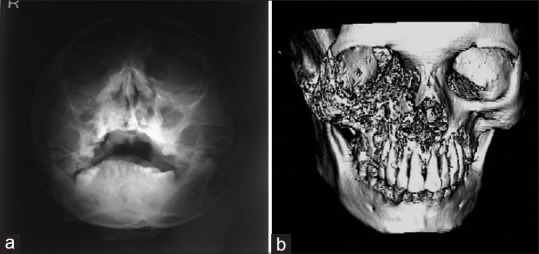

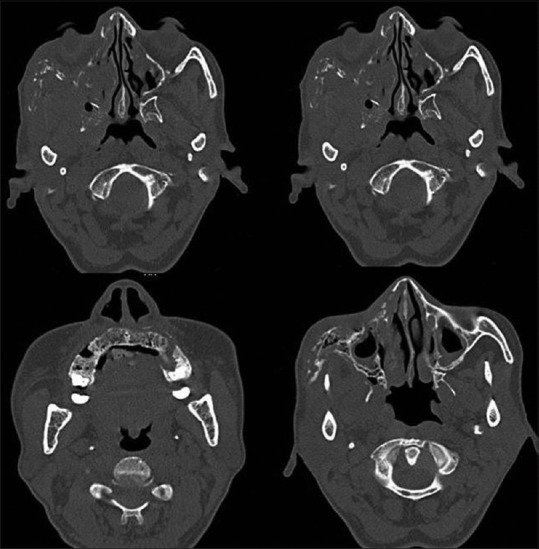

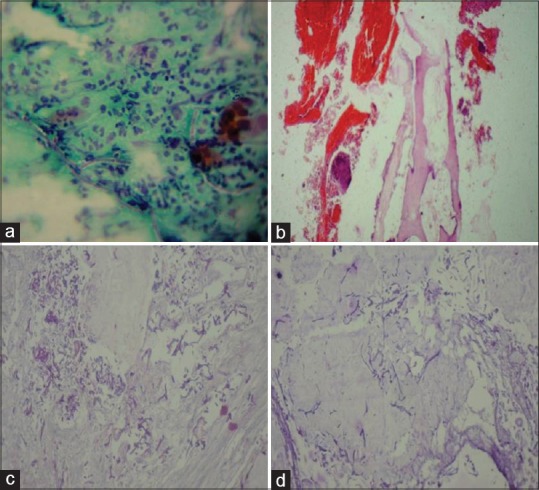

Based on the history and clinical findings, a provisional diagnosis of mucormycosis of the maxilla was made and differentials include osteomyelitis, chronic granulomatous infection, and deep fungal infections. Orthopantomogram was taken, but no significant changes were noted [Figure 2] whereas a paranasal sinus view (PNS) radiograph showed haziness of the right maxillary sinus with destruction of the sinus walls [Figure 3a]. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed hyperdensity of the maxillary antrum with destruction of all the boundaries of sinus including nasal wall and floor of the orbit [Figures 3b and 4]. On biochemical investigation, an elevated fasting blood sugar level and decreased hemoglobin% (7 g %) was noticed and HbA1c level was 8.3%. Further, cytological smear was taken from alveolar and palatal region, and Papanicolaou staining revealed numerous aseptate fungal hyphae within a background of epithelial cells and mixed inflammatory cells [Figure 5a]. Incisional biopsy was done from alveolar region, and microscopic examination under H&E revealed necrotic bone interspersed with fungal hyphae [Figure 5b]. These fungal hyphae were broad aseptate and showed branching at right angles. Further, hemorrhagic areas and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate were also seen [Figure 5c]. Special staining with periodic acid–Schiff was done which showed numerous magenta pink-colored fungal hyphae which are nonseptate showing branching at 90° [Figure 5d]. Based on radiological and histopathological findings, a final diagnosis of mucormycosis of the maxilla was given. The patient was referred to physician for increased blood sugar levels and decreased hemoglobin. Oral hypoglycemic medications were changed (Metformin 400 mg BD was changed to Gluconorm 500 mg BD). Two-unit blood transfusion was done and iron supplements were given (Venofer 800 mg which is iron sucrose solution, the drug has a pH of 10.5–11.5 which makes the alkaline environment, so the Rhizopus cannot multiply as they require acidic medium for their growth). Subsequently, surgical excision of the maxilla was done, and an acrylic plate was given as a splint. Oroantral communication was treated with primary closure and healing was normal. The excisional biopsy also revealed similar histopathological findings as that of incisional biopsy. No recurrence was noticed after 1 year of patient follow-up [Figure 6].

Figure 2.

Orthopantomogram

Figure 3.

(a) Paranasal sinus radiograph showing haziness of the right maxillary sinus with destruction of sinus walls. (b) Three-dimensional computed tomography scan showing hyperdensity of maxillary antrum with destruction of all boundaries

Figure 4.

Computed tomography images

Figure 5.

(a) Papanicolaou-stained section showing aseptate fungal hyphae (black arrow) within background of epithelial cells and inflammatory cells. (b) H and E-stained tissue section showing necrotic bone (black arrow) and hemorrhagic areas. (c) H and E-stained tissue section showing aseptate fungal hyphae branching at right angles (black arrow). (d) Periodic acid–Schiff-stained section showing magenta pink-colored aseptate fungal hyphae (black arrow)

Figure 6.

One-year follow-up total resolution of the lesion

Discussion

Mucormycosis incorporates a range of infections caused by Zygomycetes, a class of fungi that produce branching ribbon-like hyphae and reproduce sexually by formation of zygospores. Pathogen can be found ubiquitously in fruits, soil, and feces and can also be cultured from the oral cavity, nasal passages, and throat of healthy disease-free individuals. Mucorales is a subtype of Zygomycetes, which produces a distinct pattern of clinical infection. The fungi are usually avirulent; they become pathogenic only when the host resistance is exceptionally low. Ulceration in the mucosa or an extraction wound in the mouth can be a harbor of entry for mucormycosis in the maxillofacial region, particularly when the host is immunocompromised.[8]

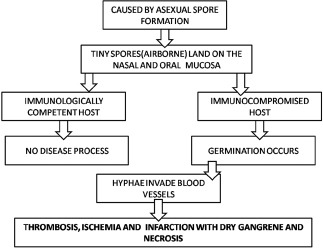

Infection by mucormycosis is caused by asexual spore formation. The tiny spores become airborne and settle on the oral and nasal mucosa of humans. In majority of immunologically competent hosts, these spores will be limited by a phagocytic response. If this response fails, germination will follow and hyphae will develop. As polymorphonuclear leukocytes are less effective in removing hyphae, in immunocompromised individuals, the infection becomes established in these cases. It further progresses as the hyphae begin to invade arteries, wherein they propagate within the vessel walls and lumens causing thrombosis, ischemia, and infarction with dry gangrene of the affected tissues. Hematogenous spread to other organs can occur (lung, brain, and so on) and results in sepsis[9] [Chart 1].

Chart 1.

Pathophysiology of mucormycosis

Mucormycosis of the oral cavity can be of two different origins. One is from disseminated infection where the gateway of entry is inhalation (through the nose) and the other is through direct wound contamination with dissemination to other viscera as a common complication. When it arises from nose and PNS, the infection may cause palatal ulceration leading to necrosis and the affected area appears black in preponderance of the cases. When the infection spreads from direct wound contamination, the clinical findings may appear anywhere in the oral cavity, including the mandible. A significant difference between infection involving the maxilla and mandible is cavernous sinus thrombosis, a serious complication of maxillary infections.[10]

Diabetes mellitus tends to change the normal immunological response of body to any infection in several ways. Hyperglycemia stimulates fungal proliferation and also causes decrease in chemotaxis and phagocytic efficiency which permits the otherwise innocuous organisms to thrive in acid-rich environment. In the diabetic ketoacidosis patient, there is an increased risk of mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus oryzae as these organisms produce the enzyme ketoreductase, which allows them to utilize the patient's ketone bodies.[8] It has been established that diabetic ketoacidosis temporarily disrupts the ability of transferrin to bind iron, and this alteration eliminates a significant host defense mechanism and permits the growth of Rhizopus oryzae.[11] In the present case, the patient presented with diabetes mellitus.

Frequent clinical presentations include rhinocerebral, pulmonary, and cutaneous forms (superficial) and less frequently, gastrointestinal, disseminated, and miscellaneous forms.[12] The rhinocerebral (rhinomaxillary) form is the most common form of infection commonly seen in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.[13] Patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis clinically present with malaise, headache, facial pain, and swelling and with low-grade fever. The disease usually initiates in the nasal mucosa or palate and extends to the paranasal sinuses spreading through the surrounding vessels such as angular, lacrimal, and ethmoidal vessels. In addition, mucormycosis can also involve the retro-orbital region by direct extension.[14] Once fungal hyphae enter into the bloodstream, they can spread to other organs such as cerebrum or lungs which can be fatal for the patient.[4]

Clinical differential diagnosis of lesion should include squamous cell carcinoma, chronic granulomatous infection such as tuberculosis, tertiary syphilis, midline lethal granuloma, and other deep fungal infections.[15]

Radiographically, opacification of sinuses may be noticed in conjunction with patchy effacement of bony walls of sinuses.[5] CT with contrast or magnetic resonance image scan can demonstrate erosion or destruction of bone and helps to know the extent of disease.[15]

Histopathologically, the lesion demonstrates broad aseptate fungal hyphae that show branching at right angles.[5] In the present case, the same histopathology was revealed. The histopathological differential diagnosis includes aspergillosis where the hyphae of Aspergillus species are septate, smaller in width and branch at more acute angles.

When diagnosed early, mucormycosis may be cured by a combination of surgical debridement of the infected area and systemic administration of amphotericin B for 3 months. Proper management of the underlying condition is also an essential aspect affecting the outcome of the treatment.[16]

Conclusion

Mucormycosis is an aggressive fulminant invasive fungal infection that can occur in patients with diverse precipitating factors such as uncontrolled diabetes, renal failure, organ transplant, long-term corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy, cirrhosis, burns, and AIDS malignancies such as lymphomas and leukemias. In a diabetic patient, it can be triggered even by minor dental procedures such as tooth extraction. Further attempts should be made for the early diagnosis of this disease and prompt management of the patient.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Viterbo S, Fasolis M, Garzino-Demo P, Griffa A, Boffano P, Iaquinta C, et al. Management and outcomes of three cases of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres-Narbona M, Guinea J, Muñoz P, Bouza E. Zygomycetes and zygomycosis in the new era of antifungal therapies. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2007;20:375–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel S, Palaskar S, Shetty VP, Bhushan A. Rhinomaxillary mucormycosis with cerebral extension. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2009;13:14–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.48743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salisbury PL, 3rd, Caloss R, Jr, Cruz JM, Powell BL, Cole R, Kohut RI, et al. Mucormycosis of the mandible after dental extractions in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:340–4. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neville WB, Damm D, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B.: Saunders; 2001. Text Book of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohindra S, Mohindra S, Gupta R, Bakshi J, Gupta SK. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: The disease spectrum in 27 patients. Mycoses. 2007;50:290–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakathir AA. Mucormycosis of the jaw after dental extractions: Two case reports. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2006;6:77–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marx RE, Stern D, editors. Carol Stream III, USA: Quintessence Publishing; 2003. Inflammatory, Reactive and Infectious Diseases in Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology; pp. 104–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kajs-Wyllie M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for rhinocerebral fungal infection. J Neurosci Nurs. 1995;27:174–81. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lador N, Polacheck I, Gural A, Sanatski E, Garfunkel A. A trifungal infection of the mandible: Case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:451–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artis WM, Fountain JA, Delcher HK, Jones HE. A mechanism of susceptibility to mucormycosis in diabetic ketoacidosis: Transferrin and iron availability. Diabetes. 1982;31:1109–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.31.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castrejon-Perez A, Welsh EC, Miranda I, Ocampo-Candiani J, Welsh O. Cutaneous Mucormycosis. Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:304–11. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spellberg B, Edwards J, Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: Pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:556–69. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.556-569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Fortson JK, Cook HE. A fatal outcome from rhinocerebral mucormycosis after dental extractions: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:693–7. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doni BR, Peerapur BV, Thotappa LH, Hippargi SB. Sequence of oral manifestations in rhino-maxillary mucormycosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:331–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.84313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burkets Textbook of Oral Medicine Diagnosis and Treatment. 10th edition. Canada: Elsevier; 2003. p. 79. [Google Scholar]