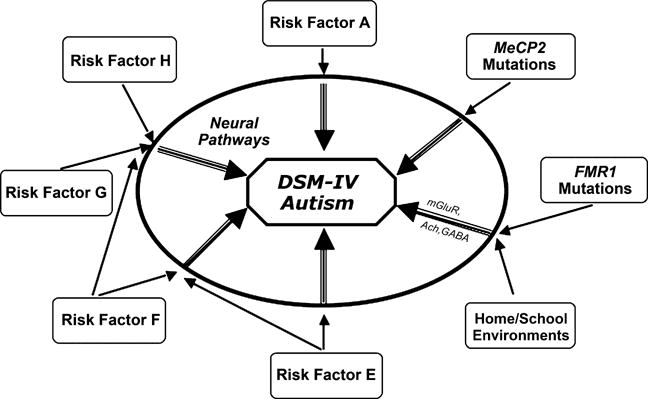

Figure 1.

A conceptualization of the current state of phenomenologically defined (e.g., DSM or ICD) disorders. In the center is a DSM-IV defined diagnosis, here shown with autism as the example. Multiple biological and environmental factors (shown around the periphery) modify risk for the development of aberrant ‘neural pathways’ during brain development. Some of these risk factors are of moderate or greater influence (e.g., MeCP2 mutations that lead to Rett syndrome shown here), and thus are able to increase the likelihood of brain dysfunction with relatively less influence from other genetic or environmental factors. Other factors, such as FMR1 mutations associated with fragile X syndrome (also shown in the figure), may contribute moderately increased risk for autistic behavior. However, this risk can be moderated by measurable environmental factors related to the home and school (Hessl et al., 2001). ‘Neural pathways’ leading to manifestations of DSM defined disorders (shown as the intermediate step between risk factors and diagnosis) also would be expected to vary for a given DSM diagnosis, even though they might result in a (somewhat) similar phenotype. Examples of neural pathways influenced by FMR1 mutations are shown in the figure (mGluR-metabotropic glutamate receptor, Ach-Acetylcholine system, GABA-gamma-aminobutyic acid). Given the lack of scientific precision of such phenomenologically based diagnostic taxonomies, alternatives to the DSM should be strongly considered for future research studies focused on elucidating the pathogenesis of (currently) idiopathic developmental disorders