Abstract

Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) are a group of noncoding RNAs that perform various biological functions, including biochemical modifications of other RNAs, precursors of miRNA, splicing, and telomerase activity. The small Cajal body associated RNAs (scaRNAs) are a subset of the snoRNA family and collect in the Cajal body where they perform their canonical function to biochemically modify spliceosomal RNAs prior to maturation. Failure of sno/scaRNAs have been implicated in pathology such as congenital heart anomalies, neuromuscular disorders, and various malignancies. Thus, understanding of sno/scaRNAs demonstrates the clinical value.

Keywords: Noncoding RNA, Small cajal body associated RNA, Spliceosomal RNA, Small nucleolar RNA, Alternative splicing

1. Introduction

The RNA derived from noncoding regions within the genome (noncoding RNA, ncRNA) has sparked great interest in medical research due to recent demonstrations of diverse developmental and regulatory roles [1, 2]. Further investigations into ncRNAs have demonstrated their complex nature and functional significance. The role of different kinds of ncRNAs has been described and ascertained in a myriad of human diseases [1, 3, 4]. However, much remains to be uncovered regarding these RNAs, particularly a subset of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) known as small Cajal body-specific RNAs (scaRNAs). Among their diverse functions, these RNAs primarily play critical roles in spliceosome formation and ribosome maturation via modification of small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), respectively [5]. This review discusses the many functions of scaRNAs including their role in disease, prognosis, and utility in clinical applications. Due to the similarities between snoRNAs and scaRNAs, the two will be denoted as sno/scaRNAs where there are shared features.

2. Classification of snoRNAs and scaRNAs

The snoRNA family can be divided into the box C/D and box H/ACA snoRNAs based on structural similarity and biochemical function. Box C/D snoRNAs form a single loop joined into a short terminal helix and contains the duplicated elements box C near the 5’ end and box D near the 3’ end [6, 7]. Function of box C/D snoRNAs require the formation of a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with the proteins 15.5K (L7Ae in archaea), Nop56, Nop58, and fibrillarin [8, 9]. Box H/ACA snoRNAs primarily take the shape of two symmetrical stem-loops where box H lies in-between the loops and box ACA near the 3’ end [6]. The H/ACA guide RNA forms a snoRNP with dyskerin, Nhp2, Nop10, and Gar1 [8]. Furthermore, both a subdivision of box C/D and H/ACA snoRNAs are localized to a specialized subnuclear organelle known as a Cajal body via a long GU repeat and Cajal body box (CAB) motif, respectively [8, 10, 11]. These subsets of RNAs are known as scaRNAs. Although scaRNAs have many functions like other snoRNAs, they also facilitate modifications of snRNAs, namely U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs [6, 11]. In total, there are at least 24 documented scaRNAs in humans, four containing box C/D, four being mixed, and the remaining have box H/ACA [12].

3. Biosynthesis, assembly, and transport of sno/scaRNPs

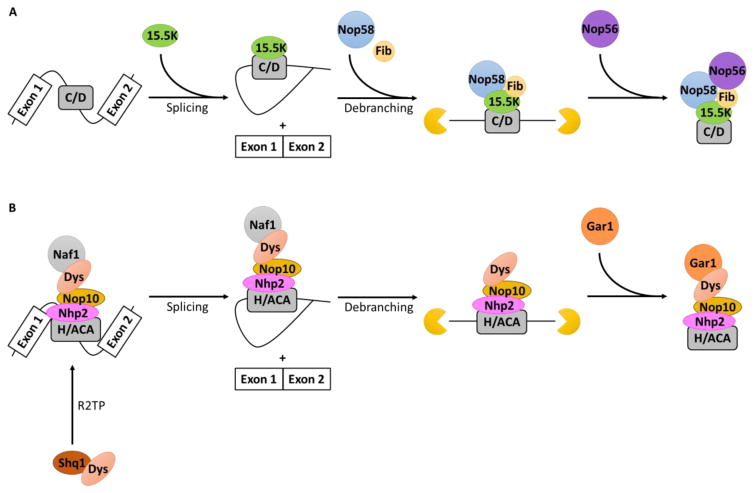

The sno/scaRNAs follow a unique biosynthetic pathway before they are transported to the Cajal bodies. Both C/D and H/ACA sno/scaRNAs are synthesized in the nucleoplasm, processed, assembled with their respective proteins, and transported to the Cajal body [13, 14]. Transcription via RNA polymerase II and RNP assembly occurs simultaneously [15]. A model of the biosynthesis and assembly of box C/D and box H/ACA RNPs is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Biogenesis of eukaryotic box C/D and H/ACA sno-/scaRNAs.

Box C/D and H/ACA scaRNAs have very similar pathways of construction. Both sequences are usually contained within intronic sequences of mRNAs which are first spliced out as a lariat structure and is then opened via a debranching enzyme. Exonucleases then degrade excess sequences at the 5’ and 3’ end of the transcript. Transcription of the guide RNA and assembly of specific proteins occur simultaneously. In the case of box C/D sno-/scaRNAs, the specific proteins are added in a stepwise fashion in the biogenesis pathway. Whereas, in box H/ACA sno-/scaRNAs, three of the factors are present at the site of transcription and only Naf1 is exchanged for Gar1 towards the end of assembly. Initially, dyskerin must be freed from the chaperone Shq1 via the chaperone complex, R2TP.

3.1 Biosynthesis of scaRNAs

Nearly all sno/scaRNAs are intronic sequences that are freed from the primary transcript by endonucleases or by splicing after mRNA processing except for SNORD3, SNODR13, SNORD118, SCARNA2, and SCARNA17 which have intrinsic promoters [13, 16–18]. Both SCARNA2 and SCARNA17 are encoded in intergenic loci and are synthesized from independent units as indicated by conserved motifs upstream [14]. Protein binding near sno/scaRNA terminals trigger exonucleases to degrade both ends of the intronic sequence until reaching the sno/scaRNA structure, where further degradation is inhibited by a bound protein and the mature sno/scaRNA is released [17, 19].

Box C/D RNAs are excised as lariats via the splicing reaction and are opened by a debranching enzyme [7]. Since box C/D RNAs are liberated by spliceosome exonuclease action, some are confined to the spliceosome, possibly by Nhp2, and are suggested to have a role in the selection of splice sites [7]. Box H/ACA RNAs are less reliant in selecting the splicing sites [7]. Additionally, the last few nucleotides of box H/ACA RNAs are processed separately [18]. In the late intermediate stage of H/ACA RNA biogenesis, poly (A) RNA polymerase D5 (PAPD5) attaches a poly(A) tail which is later removed by poly(A) specific ribonuclease (PARN) to more accurately trim the 3’ ends and prevent further shortening [18].

3.2 Assembly of scaRNPs

Binding of the 15.5K protein initiates the assembly of box C/D RNPs [20]. In archaea, the L7Ae (15.5K in eukaryotes) and sno/scaRNA complex is recognized by nucleolar protein 5 (Nop5) (Nop56 and Nop58 in eukaryotes) [21]. Binding of L7Ae forms and stabilizes the K-turn which allows Nop5 and fibrillarin to join the complex [22, 23]. In eukaryotes, Nop58 binds first with fibrillarin and Nop56 joins the complex later [20]. The N-terminal domain (NTD) is responsible for interaction with fibrillarin [21].

Assembly of H/ACA RNPs requires the specific chaperone, Shq1 which binds dyskerin (Cbf5 in archaea and NAP57 in rodents) to prevent degradation, aggregation, and binding to the premature RNA before co-transcriptional association [19, 24, 25]. Release of dyskerin from Shq1 necessitates another chaperone, the R2TP complex, which is composed of 2 ATPases (pontin and reptin), PIH1HD1 (Nop17, Pih1), and RPAP3 (hSpagh, Tah1) [24]. Pontin and reptin bind to both Shq1 and dyskerin to charge the C-terminus of dyskerin and free it from Shq1 just before its association with the guide RNA at the site of transcription [24]. Interaction between dyskerin and the H/ACA RNA occurs at the pseudouridine synthase and archaeosine transglycosylase (PUA) site of dyskerin [26]. Once dyskerin is free, Nhp2 (L7Ae in archaea) interacts directly with dyskerin and Nop10 to form a complex and join Naf1 at the site of transcription to bind to the forming H/ACA RNA; Nop10 interfaces between Nhp2 and dyskerin [27, 28]. To prevent random modifications, Naf1 remains inactivate until it is exchanged for Gar1 mediated by SMN; Gar1 only binds to dyskerin [24, 28].

3.3 Transport to Cajal bodies

Cajal bodies (CBs) are subnuclear organelles lacking a lipid bilayer and are more prominent in cells with a relatively high transcriptional load [29, 30]. These bodies function to enhance the efficiency of RNP biogenesis, splicing, telomere maintenance, rRNA processing, and DNA damage repair by CB-associated proteins and concentration of components into one area via transportation by telomerase Cajal body protein 1 (TCAB1 also known as WRAP53/WDR79) [31–33]. Coilin is a particularly important CB-associated protein protected from proteasomal degradation by vaccinia related kinase 1 (VRK1) and is often used to identify Cajal bodies [34]. Deletion of coilin in zebrafish embryos revealed that the size and number of CBs were significantly reduced and led to lethality within the first 24 hours of embryonic development. This is further evidenced by observation of incomplete embryogenesis, splicing defects, and diminished mature snRNPs in vertebrates [35].

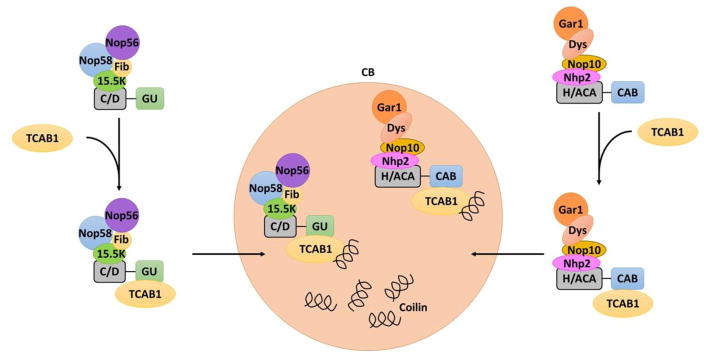

Both box C/D and H/ACA scaRNAs acquire specific sequences to localize to the CB. The C/D scaRNAs have a long GU repeat which signals for transport [8]. Similarly, H/ACA scaRNAs contain a CAB sequence within the hairpin loops as a marker for translocation [10, 11]. Transport of scaRNAs requires TCAB1, a protein that recognizes both the GU repeat and the CAB sequence [8]. More precisely, the WD-repeat within the TCAB1 protein has recently been shown to bind the CAB box in scaRNAs in both Drosophila and human cells [11]. After attachment of TCAB1, the scaRNA-TCAB1 complex is moved to the CB where TCAB1 interacts with coilin [30, 35]. Localization of scaRNAs to the CB is modeled in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Localization of scaRNA to the Cajal body.

After transcription and assembly of the scaRNP, localization to the Cajal body occurs after attachment of a localization signal, a long GU repeat in C/D scaRNAs and a CAB sequence in H/ACA scaRNAs, respectively. Both the GU repeat and CAB sequences bind TCAB1 which then translocates the complex to the Cajal body where TCAB1 interacts with coilin within the Cajal body.

4. Functions of scaRNAs

In general, scaRNAs are primarily responsible for the modifications of other RNAs, including rRNAs, snRNAs, mRNAs, and tRNAs [36]. The guide RNA is required for substrate recognition, site specificity, and assembly of the RNP [37]. The various functions of scaRNAs are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Functions of scaRNA.

The functions of scaRNAs are diverse and can be largely categorized into modifications of other RNAs or formation of derivatives that in turn perform various functions. Modifications of RNAs generally occur via two mechanisms: 2’-O-methylation by box C/D scaRNAs and pseudouridylation by box H/ACA scaRNAs. However, in the case of mRNA, modification occurs through the regulation of alternative splicing. The 3’-end of both box C/D and H/ACA RNAs can be processed into miRNAs. With the active enzyme of telomerase RNA component (TERC), the 3’-hairpin loop of H/ACA RNA is contained within the structure.

Box C/D RNA carries out 2’-O-methylation and is active in its dimeric form [7]. Identification of a target results in hybridization of the antisense sequence with its complementary sequence to the target and methylation is catalyzed by fibrillarin methyltransferase, which deposits a methyl group donated by S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) at the 2’-hydroxyl group [7, 22, 38]. Choice of the methylation site depends on its distance from the conserved box D sequence which is stringently set to five nucleotides, and methylation transpires in a short helical structure formed between the rRNA and the sno/scaRNA [39]. The methyl group prefers a 3’ endo-conformation thus prevents sugar-edge reactions and bolsters protection against hydrolysis and nucleases [22].

Pseudouridylation is one of the most common post-transcriptional modifications of RNAs and is carried out by box H/ACA RNAs [15]. The reaction is facilitated by dyskerin which functions as the pseudouridylase [40]. Isomerization of the uridine is accomplished by breakage of the N-glycosidic bond and rotation of the base into the active pocket of the enzyme; the substrate is locked into place by Gar1 [24]. Although the exact mechanism of pseudouridylation remains ambiguous, a general consensus of suggested mechanisms is a nucleophilic attack by an aspartate residue at either the C6-base or C1’-ribose [24].

4.1 Modification of rRNAs

Modifications of rRNAs by sno/scaRNAs is crucial for proper functioning of the ribosome, most likely by protection from cleavage, rRNA folding, maturation, stability, and perhaps nucleolar localization [16, 21, 39]. Although modifications of rRNA predominantly occur in the nucleolus, Deryusheva and Gall described a snoRNA which acts on the 28S ribosomal subunit in D. melanogaster and posited the possibility of processing by scaRNAs occurring outside the realm of the nucleus [11].

Cell death has been observed with complete suppression of snoRNA directed methylation [21]. Modification of target RNAs by sno/scaRNPs directed methylation stabilizes single base pairs, hydrogen bonds, and RNA folds [41]. Modifications of rRNA are usually congregated around the peptidyl-transferase and decoding centers inferring important implications for mRNA translation [39]. These methylations have been hypothesized to function in efficiency and fidelity of mRNA translation by the ribosome [39]. Pseudouridylation tends to stabilize specific RNA structures [41]. There is some conjecture of increased RNA stability due to the introduction of a hydrogen bond at the N1 position of uridine [15]. Studies of rRNA pseudouridylation defects show impaired ribosome-ligand interactions, lower ribosomal affinity for tRNAs, and reduced translational fidelity resulting in frameshifts and stop codon read-through [42].

4.2 Modification of snRNAs

Another major function of scaRNAs is a modification of snRNAs which are components of the spliceosome, during their final step of maturation [30]. The spliceosome is a complex structure composed of U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6, which are single uridine-rich RNA transcripts [43]. In addition to the snRNAs, the spliceosome contains a common core of seven Sm core proteins in a heteroheptameric ring configuration, and proteins that are specific to individual subunits [43, 44]. Furthermore, there exists a major and minor form of the spliceosome, each recognizing specific intron-exon boundary sequence [43]. The major spliceosome is U2-dependent, meaning the primary functional unit is the U2 RNP that interacts with the other RNP subunits organized around the U1, U4, and U6 RNPs [45]. The U4, U5, and U6 components form a tri-snRNP complex. In this complex, U6 is involved in catalysis by positioning metal ions to stabilize the leaving group and requires release of U4 for function; U4 acts as a chaperone to avoid deviant U6 activity [45]. Whereas, the minor spliceosome is U12-dependent and is comprised of U11, U12, U4atac, and U6atac from U12-type introns [44].

The snRNAs undergo extensive post-transcriptional modifications before the assembly with specific proteins into spliceosome RNPs that are organized around the snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, and U5) [29]. Initially, most snRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II in the nucleus, and there the transcripts obtain a monomethyl guanosine (m7G) cap and extension of the 3’ end [14]. Then the snRNA forms a complex with CBC, PHAX, ARS2, and CRM1 and is exported to the cytoplasm [45]. Once in the cytoplasm, the structure binds the SMN complex which assists loading of the Sm proteins onto the transcript that serves as a binding platform for the enzyme trimethylguanosine synthase to hypermethylate the m7G cap to 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine (m3G) [45, 46]. At this point, the excess nucleotides at the 3’ end are removed via an unknown exonucleolytic mechanism, and the pre-snRNP reenter the nucleus, via Sm and m3G cap nuclear localization signals, to accumulate within the Cajal body [14, 29, 46]. Upon entry into the CB, scaRNA U85 facilitates changes at precise locations on the snRNA and rearrangement in order to associate with snRNP-specific proteins [29]. Modification of U1 snRNA is specifically performed by scaRNA7 which guides 2’-O-methylation [12]. Methylation increases RNA stability by adjusting the RNA conformation to alter hydration space, block sugar-edge interactions, and hydrogen bonding capacity of the ribose [47]. Isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine also induces a conformational change into a more stable structure by increasing base stacking and hydrogen bonds [47]. These studies strongly demonstrated that scaRNAs are playing an important role in post-transcriptional modification through snRNAs.

4.3 Alternative splicing of mRNA

High resolution analysis of the human genome revealed only approximately 24,000 genes code for proteins [48]. Furthermore, most genes contain introns, which must be spliced out before a mature mRNA is ready to be translated. The process begins with recognition of the 5’ and 3’ splice sites by U1 and U2 snRNPs, respectively [49]. Then the U4/U5-U6 tri-snRNP is recruited to the location and loss of U1 and U4 allows a switch to the active spliceosome [49]. The mechanism of splicing occurs in two steps. In the first step, a lariat structure is formed by a 2’-hydroxyl group nucleophilic attack [50]. Then, in the next step, the lariat is freed by a second nucleophilic attack, this time from the 3’-hydroxyl group of the upstream exon [50]. Transcriptome analysis has demonstrated that most mRNAs are alternatively spliced dramatically increasing proteomic diversity. Evidence is accumulating that alternative splicing is temporally and spatially regulated and contributes to the regulation of cell differentiation and development.

As previously discussed, scaRNAs have a critical role in the maturation of spliceosomal snRNAs and thus, could play a role in alternative splicing. Additionally, noncoding RNA has been shown to be a part of exon selection by regulation of U1 binding through interaction stabilization and may occur within the pre-mRNA [50]. This is evidenced by a study using C/D RNA to modify the pre-mRNA branch point resulting in larger complexes due to binding of nonspecific proteins or more slowly migrating complexes, a product of conformational changes [51]. Another investigation showed overall impairment of splicing and reduced mRNA levels when human cells are transfected with an artificial box C/D RNA [52].

4.4 Modification of tRNAs

Modification of tRNAs via sno/scaRNAs is largely through pseudouridylation. In one study, the archaeal Cbf5-Nop10-Gar1 complex, part of box H/ACA RNPs, demonstrated high affinity for tRNAs and is capable of modified tRNA release [53]. High affinity is achieved by stabilization of the active site by Nop10 and Gar1, thereby also accentuating catalytic activity [53]. However, even though tRNAs are pseudouridylated across all species, only in archaea has RNA-guided modification been implicated and requires further investigation to determine the nature of tRNA pseudouridylation in other species [24].

4.5 Formation of miRNAs

The miRNAs are a collection of noncoding single-stranded RNAs associate with Argonaute (Ago) proteins and whose principal occupation involves downregulation of gene expression [27, 54]. Typically, miRNAs are transcribed from introns or long primary miRNA transcripts via RNA polymerase II or III [54]. However, there is data supporting the existence of numerous miRNA-like RNAs emerging from box C/D and H/ACA snoRNAs in a variety of species [27]. For instance, the miRNA targeting CDC2L6 mRNA is processed from the 3’ hairpin loop of ACA45 RNA, an H/ACA scaRNA that guides pseudouridylation of U2, and associates with Ago [27]. Another miRNA, miR2 has been shown to be derived from snoRNA GlsR17 via processing by Dicer and participates in mRNA translation in Giardia lamblia [55]. Moreover, a number of miRNA precursors, including miR-27b, miR-16-1, mir-28, miR-31 and let-7g, appear similar to box C/D RNAs, possess the same secondary structure, and bind to fibrillarin which is specific to box C/D RNAs [56]. These RNAs have been shown to have many of the equivalent characteristics as both box C/D RNAs and miRNAs with some of the same functions such as modification of other RNAs and regulation of gene expression [56]. In another study, miR-151, miR-605, mir-664, miR-215, and miR-140 have shown similarities to H/ACA RNAs and bind to dyskerin [57]. Taken together, these data suggest miRNA may have evolved from sno/scaRNAs or that sno/scaRNA sequences are a primary mechanism behind the formation of some miRNAs.

4.6 scaRNA-like TERC required for telomerase function

With each subsequent cell division, the ends of each chromosome are shortened. To prevent the gradual reduction of DNA, specialized telomere sequences are required to protect the ends of the chromosome and act as a substrate for the enzyme telomerase which preserves telomere length [58, 59]. The active enzyme consists of a telomerase RNA component (TERC), a telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), and other proteins [58]. Similar to box H/ACA scaRNAs, TERC also contains the H/ACA domain and requires the dyskerin-Nhp2-Nop10 complex, Naf1, Shq1, and pontin/reptin for stability following an analogous biogenesis pathway [58]. Comparable to scaRNAs, TERC has a CAB box sequence that binds to TCAB1 to localize to the CB [30, 35]. The localization of TERC to the CB is illustrated by the association of CBs with telomerase during the S-phase of the cell cycle. The localization seems to be essential to telomerase function since misplacement of telomerase RNA correlates with diminished telomerase activity [35]. Furthermore, the depletion of TCAB1 results in shortened telomeres. [60]. The many shared features of TERC and H/ACA RNAs suggest scaRNAs have some role in telomerase function, and further studies are essential in this field.

4.7 TERC in cardiovascular diseases

Recent studies suggest that telomerase RNA component or TERC are involved in the development and progression of atherosclerosis and heart failure. Decreased telomere length is an essential factor for the development of certain cancers, but the role of telomeres in the development of coronary heart diseases are not so far studied thoroughly. A study has shown the telomerase-deficient (telomerase RNA component, TERC / ) mice has an increased chance of hypertension compared to the normal TERC +/+ mice [61] because of producing endothelin in excess. Studies also done in older adult’s males showed WBC telomere length is inversely association diastolic blood pressure [62]. These studies further point out the possible involvement of sca/snoRNA in coronary heart diseases as sca/snoRNAs might have some importance in maintain telomere functions.

5. scaRNA in human disease

Due to the many functions of scaRNAs discussed hitherto, the potential for disease via defects of scaRNAs or its affiliated molecules are significant. Exploration of disease pathogenesis has revealed the role of noncoding RNA in a variety of ailments in several organ systems, including cardiovascular, nervous, and musculoskeletal. The role of sno/scaRNAs in tumorigenesis is well-studied, particularly in hematologic malignancies. Diseases due to various defects directly or indirectly related to scaRNA functioning are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of pathologies related to scaRNA dysfunction

| Defect | Normal Function | Pathology | Clinical Manifestations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased U2, U6 | Components of spliceosome | Tetralogy of Fallot |

|

[59], [61], [64] |

| Decreased SMN | Biosynthesis of snoRNPs, snRNPs, and telomerase RNP complex | Spinal Muscular Atrophies | Progressive muscle weakness with diminished or absent reflexes | [65], [68] |

| Mutations in DKC1 | Pseudouridine synthase, forms RNP complex | Dyskeratosis Congenita | Classic triad of nail dystrophy, abnormal pigmentation, and leukoplakia Highly correlated with increase susceptibility to bone marrow failure and cancer | [71], [72], [73] |

| Upregulation of SCARNA22 | Suppression of oxidative stress and promote cell proliferation | Multiple Myeloma | Malignancy of plasma cells | [74], [75] |

| Various | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia | Malignancy of B-lymphocytes, aggregation of mature B-cells in the blood, bone marrow, and lymphatic tissue | [77], [78] |

5.1 Sno/scaRNA in Cardiovascular Diseases

Noncoding RNAs, including sca/snoRNAs, have emerging roles in cardiovascular diseases. Recently, it has been shown that scaRNA levels present in the CMCs influence patterns of alternative splicing (AS), cardiac diseases and heart development [47, 63]. The following section summarizes the importance of these sno/scaRNAs in different cardiovascular diseases.

Tetralogy of Fallot

Dysregulation of alternative splicing has been associated with the regulation of heart development and cardiovascular diseases [64, 65]. More precisely, scaRNA has been shown to have a role in splicing and defects in splicing may contribute to severe congenital heart anomalies [63]. Of all the congenital heart diseases, tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic congenital heart defect and occurs at an incidence rate of 0.5/1,000 births [66, 67]. This condition is characterized by the tetrad of right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO), ventricular septal defects, overriding aorta, and right ventricular hypertrophy [68].

In a study done by Patil et al., 12 scaRNAs were observed to have decreased expression in the right ventricle of infants with TOF [63]. The 12 scaRNAs affected targeted only U2 and U6 snRNAs. Importantly, many genes necessary for heart development which displays alternative splice isoforms in heart tissue from the infants with TOF [63]. Upon inhibition of scaRNA expression in cell cultures, GATA4, muscleblind-like protein 1 (MBNL1), and genes of the Wnt pathway were shown to have abnormal splicing, possibly due to the lack of snRNA modifications provided by scaRNAs [63]. Both GATA4 and the Wnt pathway, among other genes, have been definitively detected in patients with TOF [66, 69]. Surprisingly, an analysis of the expression of snoRNAs in the myocardium from children with TOF shows a similar expression pattern to the fetal myocardium rather than to the snoRNA expression patterns of the myocardium from similarly aged infants with normal developing hearts. [70]. In the TOF samples, 126 snoRNAs and scaRNAs were reduced, and nine increased, similar to the 115 snoRNAs reduced and six increased in the fetal myocardium samples [70].

Although there was no direct evidence of involvement of sno/scaRNAs and coronary heart disease, a very recent study involving the human study has demonstrated the role of snoRNA and stroke. In the patient samples using unbiased next-generation sequencing and high-throughput polymerase chain reaction, the study has shown the involvement of 31 sno RNAs in this disease [71]. Since, stroke and coronary heart diseases are very much similar to the associated risk factors, these noncoding RNAs could be highly relevant in the association of heart diseases as well. Both studies support the importance of scaRNA in cardiac development and congenital heart disease. However, very few studies are available in this field.

5.2 Sno/scaRNA in other diseases

Spinal muscular atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neuromuscular degenerative disorder in which motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord deteriorate and presents clinically as progressive muscle weakness with diminished or absent reflexes [72, 73]. Relatively common, SMA has an incidence rate of 1 in 11,000 live births [74]. This condition is due to the loss of the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, however, severity is determined by the gene, SMN2 [72]. Differing degrees of severity categorize the disorder into four types (I–IV), with SMA type I being the most severe and earliest onset and SMA type IV being the least severe and latest onset [72].

Studies have shown that knockdown of SMN leads to aberrant splicing of transcripts by the major spliceosome that may contribute to motor neuron defects [75]. To reiterate, SMN is needed for both the incorporation of Gar1 into the scaRNP and for biogenesis of snRNA, both of which are important for proper spliceosome function, particularly of the major spliceosomal machinery. Altered splicing due to the loss of SMN could affect either or both points, but most studies focus only on the snRNA aspect. Additionally, both SMN1 and SMN2 undergo alternative splicing and causes SMN2 to be unable to compensate for the loss of SMN1 due to the skipping of exon 7 [76, 77].

Dyskeratosis Congenita

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a genetic condition primarily affecting the telomeres and demarcated by the classic triad of nail dystrophy, abnormal cutaneous pigmentation of upper chest and/or neck, and leukoplakia, which are white patches on the oral mucosa [15, 78]. However, diagnosis based solely on clinical presentation is not accurate since some may present differently and may appear later after other complications [78]. More significantly, DC increases the risk for progressive bone marrow failure, blood-borne cancers, solid tumors (usually of epithelial origin), and pulmonary fibrosis [78].

Of the numerous genes implicated in DC, many are required for the function of scaRNAs, such as DKC1, NHP2, NOP10, PARN, TERC, and WRAP53 [78]. Defects in DKC1, X-linked form, is widely studied and shown to lead to impairment of ribosome function [79, 80]. Knockdown experiments of dyskerin (DKC1), partial or complete, confirm defective ribosome biogenesis and maturation [80]. Faulty ribosomal maturation, especially lack of pseudouridylation, has been observed to be caused by decreased levels of H/ACA RNAs expression [40, 79, 80].

Hematologic malignancies

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable cancer derived from plasma cells and manifests as anemia, renal failure, cortical bone degradation, and hypercalcemia [81, 82]. In patients with MM, 20% express the translocation, t(4;14), which corresponds to shortened survival [81]. With this specific translocation, SCARNA22 is constitutively expressed and thereby, upregulated which is supported by analysis of the global expression profile of sno/scaRNAs in MM [83]. In a study by Chu, L., et al., SCARNA22 (also known as ACA11) overexpression contributes to oncogenesis by offering protection from oxidative stress, evasion of chemotherapy, and modulating the Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1 gene in MM cells [81]. Thus, scaRNA has a major role in the pathogenesis of MM. Similarly, in the same expression profile study of sno/scaRNAs in MM, secondary plasma cell leukemia (sPCL) also shows a basic pattern of sno/scaRNAs downregulation with the notable exception of SCARNA22 upregulation [83].

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an incurable malignancy with a B-lymphocyte origin and presents with aggregation of mature B-cells in the blood, bone marrow, and lymphatic tissue [84]. In a study of snoRNAs expression profile in patients with CLL, some remarkable differences were identified in several subsets of CLL [85]. Specifically, the high-risk group was characterized by the high expression of at least one of these ncRNAs, SNORA74A, SNORD116-18 and SCARNA17 as well as downregulation of SCARNA9 [85]. Taken together, these studies demonstrate the role of scaRNAs in the development of cancer.

6. Clinical implications

The critical role of scaRNAs in many biological processes and development, defects in any of its function can contribute to malfunctions and disease. Thus, scaRNAs should have potential relevance in diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy.

6.1 Diagnostic biomarkers

In general terms, noncoding RNAs are attractive as biomarkers because they are stable in circulation and biological fluids, such as urine [86, 87]. Additionally, many snoRNAs are tissue-specific, thus they can be used to narrow down a disease process to a location [88]. In a recent study, combinatorial miRNA and snoRNA showed greater ability to accurately detect lung cancer than compared to either family of noncoding RNAs alone [89]. Hence, combinations of noncoding RNAs can add precision to diagnoses.

The scaRNA-like TERC is already used as a diagnostic tool to identify DC. Likewise, scaRNAs have been shown to have a differential expression in subtypes of CLL and thereby, have potential to be used as markers to discriminate between subgroups and focus treatment. Furthermore, scaRNAs have prognostic value and may pinpoint the exact molecular subtype as in the case of MM. However, information regarding the extent of scaRNAs involvement in disease is scant. Their counterpart, the snoRNAs, has been more meticulously studied. Currently, a plethora of snoRNAs have already been correlated with several cancers, including cancers of endocrine origin [86], prostate cancer [87, 90], and lung cancer [89] and their differential expression may govern prognosis. In non-small cell lung cancer, an H/ACA snoRNA corresponds with a poorer prognosis [91]. Additionally, scaRNAs may be used to predict response to therapy as previously discussed with the association between SCARNA22 and resistance to chemotherapy in MM. Although noncoding RNAs showed great promise as diagnostic and prognostic markers, currently there is no standardized protocol for mechanistic analysis, and there is a clear need for better understanding of snoRNA contribution to disease [86].

6.2 Therapeutic agents

Anomalous splicing has been implicated in numerous diseases, including congenital heart defects and spinal muscular atrophy. Many studies have shown that cancer cells use alternative splicing to achieve many of the hallmarks of cancer: proliferation, immortality, and escapingimmune system detection [92]. Therefore, due to the importance of splicing in disease pathogenesis, inhibition of scaRNAs may be beneficial. Since scaRNAs modify spliceosomal components and participate in mRNA alternative splicing, they can be used as targets or to direct inhibition of splicing. In particular, C/D box RNAs have been shown to be capable of prohibiting splicing via 2’-O-methylation at the branch point as stated before. In addition, the therapeutic agent 5-fluororidine (5-FU), acts by integrating into U2 snRNA to block pseudouridylation and has been used to treat solid tumors [47]. Future studies are needed to target disease-specific scaRNAs as a therapeutic intervention in animal models to delineate scaRNAs as an important molecular target for various diseases.

7. Conclusion

The recent tremendous increase in research on the biology of noncoding RNAs reflects their enormous potential for understanding human health and pathology. As investigators delve deeper into this mysterious group of molecules, their functional and mechanistic complexity continues to expand. The family of scaRNAs have received relatively less attention, but the demonstration of the role they play in spliceosome function and their association with various developmental disorders suggests there is still much to be learned about this subfamily of noncoding RNAs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 16GRNT30950010 and National Institutes of Health COBRE grant P20GM104936 (to JR).

Abbreviations

- AGO

Argonaute

- CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- CB

Cajal body

- CTD

Carboxyl-terminal domain

- DC

Dyskeratosis congenita

- DKC1

Dyskeratosis congenita gene 1

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- MBNL1

Muscleblind-like protein 1

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- miRNA

Micro RNA

- ncRNA

Noncoding RNA

- Nop

Nucleolar protein

- NTD

N-terminal domain

- PARN

poly(A) specific ribonuclease

- PAPD5

Poly (A) RNA polymerase D5

- rRNA

Ribosomal RNAs

- RNP

Ribonucleoprotein

- RVOT

Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- R2TP

Rvb1-Rvb2-Tah1-Pih1

- SAM

S-adenosyl-methionine

- SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy

- SMN1

Survival motor neuron 1

- snoRNAs

Small nucleolar RNAs

- scaRNAs

Small Cajal body associated RNAs

- snRNAs

Small nuclear RNAs

- snoRNAs

Small nucleolar RNAs

- TCAB1

Telomerase cajal body protein 1

- TERC

Telomerase RNA component

- TOF

Tetrology of Fallot

- VRK1

Vaccinia related kinase 1

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Thuy Cao, Saheli Samanta wrote the article; Thuy Cao, and Sheeja Rajasingh contributed in drawing figures; Buddhadeb Dawn and Douglas C. Bittel helped in editing the manuscript; Johnson Rajasingh provided valuable insights about non-coding RNA biology as well as conceptual advice and helped writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer discovery. 2011;1(5):391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patil VS, Zhou R, Rana TM. Gene regulation by noncoding RNAs. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2014;49(1):16–32. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.844092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(12):861–74. doi: 10.1038/nrg3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wapinski O, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs and human disease. Trends in Cell Biology. 2011;21(6):354–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massenet S, Bertrand E, Verheggen C. Assembly and trafficking of box C/D and H/ACA snoRNPs. RNA biology. 2016:1–13. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1243646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marz M, Gruber AR, Honer Zu Siederdissen C, Amman F, Badelt S, Bartschat S, et al. Animal snoRNAs and scaRNAs with exceptional structures. RNA Biol. 2011;8(6):938–46. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.6.16603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falaleeva M, Pages A, Matuszek Z, Hidmi S, Agranat-Tamir L, Korotkov K, et al. Dual function of C/D box small nucleolar RNAs in rRNA modification and alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113(12):E1625–E34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519292113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorjani H, Kehr S, Jedlinski DJ, Gumienny R, Hertel J, Stadler PF, et al. An updated human snoRNAome. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44(11):5068–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleichert F, Baserga SJ. Dissecting the role of conserved box C/D sRNA sequences in di-sRNP assembly and function. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(22):8295–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishore S, Gruber AR, Jedlinski DJ, Syed AP, Jorjani H, Zavolan M. Insights into snoRNA biogenesis and processing from PAR-CLIP of snoRNA core proteins and small RNA sequencing. Genome biology. 2013;14(5):R45. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-5-r45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deryusheva S, Gall JG. Novel small Cajal-body-specific RNAs identified in Drosophila: probing guide RNA function. RNA (New York, NY) 2013;19(12):1802–14. doi: 10.1261/rna.042028.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enwerem II, Velma V, Broome HJ, Kuna M, Begum RA, Hebert MD. Coilin association with Box C/D scaRNA suggests a direct role for the Cajal body marker protein in scaRNP biogenesis. Biology open. 2014;3(4):240–9. doi: 10.1242/bio.20147443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marnef A, Richard P, Pinzon N, Kiss T. Targeting vertebrate intron-encoded box C/D 2'-O-methylation guide RNAs into the Cajal body. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(10):6616–29. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerard MA, Myslinski E, Chylak N, Baudrey S, Krol A, Carbon P. The scaRNA2 is produced by an independent transcription unit and its processing is directed by the encoding region. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(2):370–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang B, Li H. Structures of ribonucleoprotein particle modification enzymes. Quarterly reviews of biophysics. 2011;44(1):95–122. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makarova JA, Kramerov DA. SNOntology: Myriads of novel snoRNAs or just a mirage? BMC genomics. 2011;12:543. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilusz JE. Long noncoding RNAs: Re-writing dogmas of RNA processing and stability. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1859(1):128–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berndt H, Harnisch C, Rammelt C, Stohr N, Zirkel A, Dohm JC, et al. Maturation of mammalian H/ACA box snoRNAs: PAPD5-dependent adenylation and PARN-dependent trimming. RNA (New York, NY) 2012;18(5):958–72. doi: 10.1261/rna.032292.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupuis-Sandoval F, Poirier M, Scott MS. The emerging landscape of small nucleolar RNAs in cell biology. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews RNA. 2015;6(4):381–97. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richard P, Kiss T. Integrating snoRNP assembly with mRNA biogenesis. EMBO reports. 2006;7(6):590–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapinaite A, Simon B, Skjaerven L, Rakwalska-Bange M, Gabel F, Carlomagno T. The structure of the box C/D enzyme reveals regulation of RNA methylation. Nature. 2013;502(7472):519–23. doi: 10.1038/nature12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis PP, Tripp V, Lui L, Lowe T, Randau L. C/D box sRNA-guided 2′-O-methylation patterns of archaeal rRNA molecules. BMC genomics. 2015;16:632. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1839-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su AAH, Tripp V, Randau L. RNA-Seq analyses reveal the order of tRNA processing events and the maturation of C/D box and CRISPR RNAs in the hyperthermophile Methanopyrus kandleri. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(12):6250–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu Y-T, Meier UT. RNA-guided isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine—pseudouridylation. RNA biology. 2014;11(12):1483–94. doi: 10.4161/15476286.2014.972855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, Duan J, Li D, Ma S, Ye K. Structure of the Shq1–Cbf5–Nop10 Gar1 complex and implications for H/ACA RNP biogenesis and dyskeratosis congenita. The EMBO journal. 2011;30(24):5010–20. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J, Liang B, Li H. Structural and functional evidence of high specificity of Cbf5 for ACA trinucleotide. RNA (New York, NY) 2011;17(2):244–50. doi: 10.1261/rna.2415811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiss T, Fayet-Lebaron E, Jady BE. Box H/ACA small ribonucleoproteins. Molecular cell. 2010;37(5):597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koo BK, Park CJ, Fernandez CF, Chim N, Ding Y, Chanfreau G, et al. Structure of H/ACA RNP protein Nhp2p reveals cis/trans isomerization of a conserved proline at the RNA and Nop10 binding interface. Journal of molecular biology. 2011;411(5):927–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strzelecka M, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Luhrmann R, Oates AC, Neugebauer KM. Coilin-dependent snRNP assembly is essential for zebrafish embryogenesis. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2010;17(4):403–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broome HJ, Hebert MD. Coilin displays differential affinity for specific RNAs in vivo and is linked to telomerase RNA biogenesis. Journal of molecular biology. 2013;425(4):713–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broome HJ, Carrero ZI, Douglas HE, Hebert MD. Phosphorylation regulates coilin activity and RNA association. Biology open. 2013;2(4):407–15. doi: 10.1242/bio.20133863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriksson S, Farnebo M. On the road with WRAP53beta: guardian of Cajal bodies and genome integrity. Frontiers in genetics. 2015;6:91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enwerem II, Wu G, Yu YT, Hebert MD. Cajal body proteins differentially affect the processing of box C/D scaRNPs. PloS one. 2015;10(4):e0122348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantarero L, Sanz-Garcia M, Vinograd-Byk H, Renbaum P, Levy-Lahad E, Lazo PA. VRK1 regulates Cajal body dynamics and protects coilin from proteasomal degradation in cell cycle. Scientific reports. 2015;5:10543. doi: 10.1038/srep10543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machyna M, Neugebauer KM, Staněk D. Coilin: The first 25 years. RNA biology. 2015;12(6):590–6. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1034923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tortoriello G, Accardo MC, Scialo F, Angrisani A, Turano M, Furia M. A novel Drosophila antisense scaRNA with a predicted guide function. Gene. 2009;436(1–2):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamma T, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. The Box H/ACA Ribonucleoprotein Complex: Interplay of RNA and Protein Structures in Post-transcriptional RNA Modification. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285(2):805–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.076893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Nues RW, Watkins NJ. Unusual C'/D' motifs enable box C/D snoRNPs to modify multiple sites in the same rRNA target region. Nucleic acids research. 2016 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motorin Y, Helm M. RNA nucleotide methylation. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews RNA. 2011;2(5):611–31. doi: 10.1002/wrna.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matera AG, Terns RM, Terns MP. Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8(3):209–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watkins NJ, Bohnsack MT. The box C/D and H/ACA snoRNPs: key players in the modification, processing and the dynamic folding of ribosomal RNA. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews RNA. 2012;3(3):397–414. doi: 10.1002/wrna.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jack K, Bellodi C, Landry DM, Niederer RO, Meskauskas A, Musalgaonkar S, et al. rRNA pseudouridylation defects affect ribosomal ligand binding and translational fidelity from yeast to human cells. Molecular cell. 2011;44(4):660–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urlaub H, Raker VA, Kostka S, Luhrmann R. Sm protein-Sm site RNA interactions within the inner ring of the spliceosomal snRNP core structure. The EMBO journal. 2001;20(1–2):187–96. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deryusheva S, Choleza M, Barbarossa A, Gall JG, Bordonne R. Post-transcriptional modification of spliceosomal RNAs is normal in SMN-deficient cells. RNA (New York, NY) 2012;18(1):31–6. doi: 10.1261/rna.030106.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bizarro J, Dodre M, Huttin A, Charpentier B, Schlotter F, Branlant C, et al. NUFIP and the HSP90/R2TP chaperone bind the SMN complex and facilitate assembly of U4-specific proteins. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43(18):8973–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyjek M, Wojciechowska N, Rudzka M, Kolowerzo-Lubnau A, Smolinski DJ. Spatial regulation of cytoplasmic snRNP assembly at the cellular level. Journal of experimental botany. 2015;66(22):7019–30. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karijolich J, Yu YT. Spliceosomal snRNA modifications and their function. RNA Biol. 2010;7(2):192–204. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.2.11207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome research. 2012;22(9):1760–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.135350.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen M, Manley JL. Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2009;10(11):741–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelemen O, Convertini P, Zhang Z, Wen Y, Shen M, Falaleeva M, et al. Function of alternative splicing. Gene. 2013;514(1):1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ge J, Liu H, Yu YT. Regulation of pre-mRNA splicing in Xenopus oocytes by targeted 2'-O-methylation. RNA (New York, NY) 2010;16(5):1078–85. doi: 10.1261/rna.2060210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stepanov GA, Semenov DV, Savelyeva AV, Kuligina EV, Koval OA, Rabinov IV, et al. Artificial box C/D RNAs affect pre-mRNA maturation in human cells. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:656158. doi: 10.1155/2013/656158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamalampeta R, Kothe U. Archaeal proteins Nop10 and Gar1 increase the catalytic activity of Cbf5 in pseudouridylating tRNA. Scientific reports. 2012;2:663. doi: 10.1038/srep00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samanta S, Balasubramanian S, Rajasingh S, Patel U, Dhanasekaran A, Dawn B, et al. MicroRNA: A new therapeutic strategy for cardiovascular diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26(5):407–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saraiya AA, Wang CC. snoRNA, a Novel Precursor of microRNA in Giardia lamblia. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4(11):e1000224. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ono M, Scott MS, Yamada K, Avolio F, Barton GJ, Lamond AI. Identification of human miRNA precursors that resemble box C/D snoRNAs. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(9):3879–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott MS, Avolio F, Ono M, Lamond AI, Barton GJ. Human miRNA Precursors with Box H/ACA snoRNA Features. PLoS Computational Biology. 2009;5(9):e1000507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freund A, Zhong FL, Venteicher AS, Meng Z, Veenstra TD, Frydman J, et al. Proteostatic control of telomerase function through TRiC-mediated folding of TCAB1. Cell. 2014;159(6):1389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chartrand P. Special focus on telomeres and telomerase. RNA biology. 2016;13(8):681–2. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1211223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Artandi SE, DePinho RA. Telomeres and telomerase in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):9–18. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez-Rivero G, Ruiz-Torres MP, Rivas-Elena JV, Jerkic M, Diez-Marques ML, Lopez-Novoa JM, et al. Mice deficient in telomerase activity develop hypertension because of an excess of endothelin production. Circulation. 2006;114(4):309–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Gardner JP, Psaty BM, Jenny NS, Tracy RP, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the cardiovascular health study. American journal of epidemiology. 2007;165(1):14–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patil P, Kibiryeva N, Uechi T, Marshall J, O'Brien JE, Jr, Artman M, et al. scaRNAs regulate splicing and vertebrate heart development. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1852(8):1619–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalsotra A, Wang K, Li PF, Cooper TA. MicroRNAs coordinate an alternative splicing network during mouse postnatal heart development. Genes Dev. 2010;24(7):653–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1894310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lara-Pezzi E, Dopazo A, Manzanares M. Understanding cardiovascular disease: a journey through the genome (and what we found there) Dis Model Mech. 2012;5(4):434–43. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Villafane J, Feinstein JA, Jenkins KJ, Vincent RN, Walsh EP, Dubin AM, et al. Hot topics in tetralogy of Fallot. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62(23):2155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeng Z, Zhang H, Liu F, Zhang N. Current diagnosis and treatments for critical congenital heart defects. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2016;11(5):1550–4. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Animasahun BA, Madise-Wobo AD, Falase BA, Omokhodion SI. The burden of Fallot’s tetralogy among Nigerian children. Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. 2016;6(5):453–8. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.05.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bittel DC, Butler MG, Kibiryeva N, Marshall JA, Chen J, Lofland GK, et al. Gene expression in cardiac tissues from infants with idiopathic conotruncal defects. BMC medical genomics. 2011;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Brien JE, Jr, Kibiryeva N, Zhou XG, Marshall JA, Lofland GK, Artman M, et al. Noncoding RNA expression in myocardium from infants with tetralogy of Fallot. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5(3):279–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mick E, Shah R, Tanriverdi K, Murthy V, Gerstein M, Rozowsky J, et al. Stroke and Circulating Extracellular RNAs. Stroke. 2017;48(4):828. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cao Y-y, Qu Y-j, He S-x, Li Y, Bai J-l, Jin Y-w, et al. Association between SMN2 methylation and disease severity in Chinese children with spinal muscular atrophy. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 2016;17(1):76–82. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garg N, Park SB, Vucic S, Yiannikas C, Spies J, Howells J, et al. Differentiating lower motor neuron syndromes. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Neurologic clinics. 2015;33(4):831–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.See K, Yadav P, Giegerich M, Cheong PS, Graf M, Vyas H, et al. SMN deficiency alters Nrxn2 expression and splicing in zebrafish and mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23(7):1754–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yoshimoto S, Harahap NIF, Hamamura Y, Ar Rochmah M, Shima A, Morisada N, et al. Alternative splicing of a cryptic exon embedded in intron 6 of SMN1 and SMN2. Human Genome Variation. 2016;3:16040. doi: 10.1038/hgv.2016.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seo J, Singh NN, Ottesen EW, Lee BM, Singh RN. A novel human-specific splice isoform alters the critical C-terminus of Survival Motor Neuron protein. Scientific reports. 2016;6:30778. doi: 10.1038/srep30778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Savage SA. Dyskeratosis Congenita. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R) Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bellodi C, McMahon M, Contreras A, Juliano D, Kopmar N, Nakamura T, et al. H/ACA small RNA dysfunctions in disease reveal key roles for noncoding RNA modifications in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell reports. 2013;3(5):1493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gu BW, Apicella M, Mills J, Fan JM, Reeves DA, French D, et al. Impaired Telomere Maintenance and Decreased Canonical WNT Signaling but Normal Ribosome Biogenesis in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from X-Linked Dyskeratosis Congenita Patients. PloS one. 2015;10(5):e0127414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chu L, Su MY, Maggi LB, Lu L, Mullins C, Crosby S, et al. Multiple myeloma–associated chromosomal translocation activates orphan snoRNA ACA11 to suppress oxidative stress. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122(8):2793–806. doi: 10.1172/JCI63051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.López-Corral L, Mateos MV, Corchete LA, Sarasquete ME, de la Rubia J, de Arriba F, et al. Genomic analysis of high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2012;97(9):1439–43. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.060780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ronchetti D, Todoerti K, Tuana G, Agnelli L, Mosca L, Lionetti M, et al. The expression pattern of small nucleolar and small Cajal body-specific RNAs characterizes distinct molecular subtypes of multiple myeloma. Blood cancer journal. 2012;2:e96. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2012.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li X-L, Zhang C-X. New emerging therapies in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncology Letters. 2016;12(5):3051–4. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ronchetti D, Mosca L, Cutrona G, Tuana G, Gentile M, Fabris S, et al. Small nucleolar RNAs as new biomarkers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. BMC medical genomics. 2013;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Venkatesh T, Suresh PS, Tsutsumi R. Non-coding RNAs: Functions and applications in endocrine-related cancer. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2015;416:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crea F, Quagliata L, Michael A, Liu HH, Frumento P, Azad AA, et al. Integrated analysis of the prostate cancer small-nucleolar transcriptome reveals SNORA55 as a driver of prostate cancer progression. Molecular oncology. 2016;10(5):693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Alahari SV, Eastlack SC, Alahari SK. Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Neoplasia: Special Emphasis on Prostate Cancer. International review of cell and molecular biology. 2016;324:229–54. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Su Y, Guarnera MA, Fang H, Jiang F. Small non-coding RNA biomarkers in sputum for lung cancer diagnosis. Molecular Cancer. 2016;15:36. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0520-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martens-Uzunova ES, Hoogstrate Y, Kalsbeek A, Pigmans B, Vredenbregt-van den Berg M, Dits N, et al. C/D-box snoRNA-derived RNA production is associated with malignant transformation and metastatic progression in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17430–44. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mei YP, Liao JP, Shen J, Yu L, Liu BL, Liu L, et al. Small nucleolar RNA 42 acts as an oncogene in lung tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2012;31(22):2794–804. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oltean S, Bates DO. Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33(46):5311–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]