Abstract

Context:

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) have become primary or secondary outcome measure in clinical trials and epidemiological studies in Medicine and Dentistry in general and Periodontology in particular. PROs are patients' self-perceptions about consequences of a disease or its treatment. They can be used to measure the impact of the disease or the effect of its treatment. There are insufficient data in Periodontology related to scale development methodology although, recently, there is an increase in the number of published studies utilizing such tools in major journals.

Aim:

This paper is an overview of the development methodology of new PRO tools to study the impact of periodontal disease.

Materials and Methods:

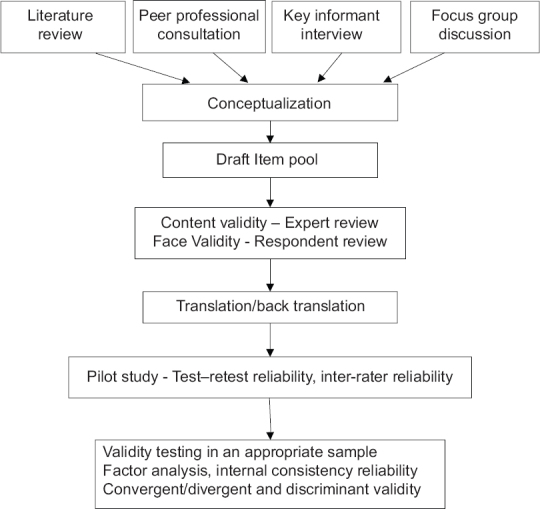

The iterative process begins with a research question. A well-constructed a priori hypothesis enables validity assessment by hypothesis testing. The qualitative steps in item generation include literature review, focus group discussion, and key informant interviews. Expert paneling, content validity index, and pretesting are done to refine and sequence the items. Test–retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and internal consistency reliability are assessed. The tool is administered in a representative sample to test construct validity by factor analysis.

Conclusion:

The steps involved in developing a subjective perception scale are complicated and should be followed to establish the essential psychometric properties. The use of existing tool, if it fulfills the research objective, is recommended after cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric testing.

Key words: Oral health, patient outcome assessment, patient-reported outcome measures, periodontitis, quality of life, reliability, validity

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is the second largest oral health problem, affecting 10%–15% of the world's population.[1] Recently, the importance of periodontal health care has received more attention based on the reported association between periodontal health and many major systemic diseases.[2,3] Clinical parameters such as clinical attachment level (CAL) and probing pocket depth have traditionally been used as surrogate measures to assess periodontal disease as well as treatment outcomes. However, the inflammation and tissue destruction associated with periodontal disease produce a wide range of clinical signs and symptoms, some of which may have a considerable impact on day-to-day life or life quality.[4] Information in this regard seems inadequate at present. It was Cohen and Jago who first introduced the concept of measuring patients' perceptions regarding health conditions.[5] Many studies have included patients' self-reported data as a measure of periodontal disease and therapy. This is based on the recognition of the biopsychosocial approach to disease and health conditions, a concept based on the premises that disease potentially impacts the psychology and functions and social behavior of the sufferer over and above its biological effects.[6]

The significance of patient-reported outcome (PRO) or patient-based outcome assessment in periodontal therapy was designated a research priority area at the 2003 World Workshop on Emerging Science in Periodontology.[7] These measures are useful in many fronts. The health-care systems tend to be consumer driven, and the patients are the primary beneficiaries of therapy. The understanding of consequences of the disease and the effects of its treatment can help evaluate treatment outcomes in clinical practice and controlled trials. It can also aid in the planning and evaluation of public health interventions and for optimum allocation of resources.[8]

The PROs regarding various dental diseases and their treatment are basically psychometric tests. A psychometric test measures differences among individuals and groups in psychosocial qualities such as attitudes and perceptions. These tests are often a battery of questions known as a tool or scale developed based on theoretical constructs concerning the context of application. They can be used to measure the impact of the disease or the effect of its treatment in people. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) tools and global self-ratings of oral health (usually a single-item tool) are subjective measures of the impact of disease consequences. The PRO tools are employed for the assessment of the effect of treatment from a patient's perspective and/or satisfaction with treatment. Many established scales such as the oral health impact profile (OHIP) and the oral impacts on daily performance (OIDP) are OHRQoL tools utilized in longitudinal clinical studies as outcome measures.

Most of the OHRQoL measures developed and used are based on Locker's conceptual model adapted from the International Classification of Impairment, Disability, and Handicap of the WHO.[4] Most of the OHRQoL tools that have been used to measure the impact of periodontal disease are generic tools that are employed to measure other oral conditions such as dental caries or malocclusion.

GENERIC AND SPECIFIC ORAL HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE TOOLS

Instruments used to measure OHRQoL are known as scales, indices, tools, etc. The OHRQoL scales were earlier known as sociodental indicators. Global self-ratings of oral health (GSROH) is a simple tool that provides self-perception of oral health in a quick and cost-effective manner.[9] GSROH is highly valuable in a low-resource setting for summarizing oral health status of a population.[10] OHRQoL scales can be generic or specific. Generic tools are nonspecific which can be used for any oral condition or disease. Generic scales allow comparisons across various disorders and their relationship to demographic and cultural differences. They have wide bandwidth but less fidelity. Specific tools can be of two types – condition specific (oral cancer related, malocclusion related, or periodontal disease related) or population specific (elderly, schoolchildren, adolescents, etc). As the scale becomes more specific, the generalizability diminishes. They have high fidelity but narrow bandwidth. Literature review reveals that there are limited data available regarding a widely accepted specific tool to measure periodontal disease impact as well as the effect of therapy. Therefore, a need exists for the development of a reliable and valid disease-specific tool which can detect subtle differences perceived by patients, related to periodontal disease and its therapy.

Developing a PRO tool is a strenuous process, with standard methodology involving sequential or at times overlapping steps [outlined in Figure 1]. There can be minimal differences in the steps based on the specificity of context of disease or treatment, but essentially, it should be followed in the development process of psychosocial tools. When OHRQoL tools are used extensively to evaluate PRO measures, it is important to know the methodological and psychometric process involved in its development.[11] There is scarcity of articles in Periodontology related to tool development methodology although there is a recent increase in the number of published studies utilizing such tools in major journals. For an in-depth understanding of tool development process, one can refer to dedicated textbooks.[12,13] The following is an overview of the essentials regarding developing a new psychometric tool to study the impact of periodontal disease, which may be applicable for other oral diseases or conditions.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing sequential steps in patient-reported outcome measure development

STRUCTURE OF A TOOL

As with any form of medical or dental research, tool development begins with a research question and one need to constantly refer back to it during the development process.[14] Having a well-framed theoretical construct with a priori hypothesis will enable the researcher to carry out validity assessment of the tool by testing the hypotheses at the end of scale development. A health measurement tool may also be developed without a hypothesis. Sound theoretical understanding of the condition or context you want to measure is the stepping stone in the conceptualization process.

ITEMS AND DOMAINS

The basic unit of a tool is known as an item. It can be either in the form of a question or a statement. Questions can be open ended or closed.[15] Open-ended questions are essential elements in a qualitative interview or focus group discussion (FGD) in the initial stages of tool development process as they enable the respondents to open up their minds. As items get refined in the process, they are of little value in the final tool. The general guidelines for item construction are the following:

Include minimum number of items (usually a minimum of three per domain)

Questions should be short and to the point

They should be based on the scale's objective

Respondents should be able to comprehend the questions.

Avoid embarrassing or socioculturally sensitive questions.

Use simple language and avoid jargon terms.

Avoid double-barreled questions (those that ask two different things in one question with two different responses possible).

Related items that define a part of the construct or domain are grouped together as subscales.[16] This process can be done initially by the researcher himself or subject experts and later during factor analysis based on factor loading. For example, bleeding from gingiva is a common sign of periodontal disease. There may be multiple questions to tap the presence of gingival bleeding during various activities (spotting blood on the toothbrush or in spit while brushing, taste of blood in saliva on waking up, bleeding while eating or speaking, etc). Similarly, items which tap the presence of sensitivity or pain also come under one domain – signs and symptoms or physical domain. There may be multiple domains in a scale. OHIP 14 is the short version of OHIP which is a 14-item questionnaire.[17] There are seven domains in OHIP 14 which are functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. Each domain in the scale is represented by two questions. The number of items in each domain need not be the same in a scale. If one domain has more items, then it contributes more to the total score. This is acceptable if that domain is more important, but if all the domains in the scale are of equal importance and each item contributes equally to the total score, then each domain should have a uniform number of items.

There is no rule that the number of items in each domain should be the same rather it depends on the importance of the domain.

Response options

The nature and intent of the item dictates the type of response option. The response format can be basically categorical (yes/no) or continuous (none/some/a lot) depending on how much information the researcher wants and how much the respondent can discriminate among the options. The most common response format used in OHRQoL tools is a Likert scale usually with five-point response options (strongly agree/agree/neutral/disagree/strongly disagree). The Likert scale, named after its inventor Psychologist Rensis Likert, is a psychometric scale commonly involved in survey research that employs questionnaires.[18] Even though regarded as an ordinal scale, when it is symmetric and the options are equidistant, the Likert scale will behave more like an interval-level measurement. Alternatively, the visual analog scale which is a psychometric response scale used to measure subjective characteristics such as pain that cannot be directly measured may be used.[12] The choice of response option depends on the nature of the question asked. The response option for the OHIP questionnaire is a five-point Likert scale with the options “very often, fairly often, occasionally, hardly ever, and never”. For any response, the respondent needs to understand the question, recall the behavior, attitude or belief, and extrapolate the memory to give a genuine answer. This process can be a potential source of bias in response. The administration of questionnaire can be self-completed or by the investigator or by a member of the investigating/treating team. The process of administration should be standardized for all the participants in a particular study. The response thus obtained is given ordinal scores and converted into numerical form usually by adding the scores together to get a total score and a domain-wise subtotal (if appropriate) for analytical purposes. Items that tap the opposite aspect of a trait need score reversal before calculating the total score. Individual domain scores facilitate comparison between domains. If the number of items in the domain that are being compared is not the same, then interdomain comparison is not easy. Similarly, when two different scales with dissimilar number of items need to be compared, then a process called scale transformation is required to enable comparison between them. Scale transformation is a process of transforming the raw scale score to facilitate interpretation.[12]

ITEM GENERATION

Item source

Before beginning to develop a new tool, it is recommended to do a thorough literature search to find the availability of any existing tool for the current research objective. Even if an existing tool as such cannot be utilized, a few items and/or domains can be adapted, if found appropriate, to the new tool. This applies to both generic tools and condition-specific tools. Generic tools such as OHIP and its short version (OHIP-14), OIDP, and Oral Health Related Quality of Life in UK (OHQoL-UK) and a periodontal disease-specific tool – periodontal disease impact on life quality – have been used by various investigators to study the periodontal disease-related QoL.[19] Items from an existing tool are highly valuable since they have already undergone item analysis and their reliability and validity stand established. Patients experiencing periodontal disease can be a good source for item generation. FGDs and key informant (patient/sufferer) interviews can be utilized to acquire subjective viewpoints in a systematic manner. Evidence-based literature reviews and discussion with subject experts are essential elements of the conceptualization process, which is the cornerstone of item generation. A theoretical model is developed and hypotheses generated. Based on the theoretical model, the item pool is derived. These steps will ensure the content validity of the tool which is the foundation for a reliable and valid tool.

Item quality

Items in a tool should be presented in a simple language such that it should be understandable to 12 years old. Technical words such as furcation involvements or trauma from occlusion should be avoided. Double-barreled questions should be avoided. Single-item global rating questions and open-ended questions are employed for tapping patient perceptions beyond the boundary of tool, but such items are less amenable to statistical analysis. Items in a periodontal disease-specific tool should have good discriminatory capacity, i.e., they should be able to discriminate between individuals having the disease from periodontally healthy individuals based on scale scores.

ITEM REFINEMENT AND SEQUENCING

The draft item pool generated in the initial phase should have more items than what is required for the final tool because item reduction will be done at various levels in the process of scale development. Nothing can be done later to compensate for an item which is omitted at the initial stage. A panel of experts helps to decide upon the relevance, sequencing, and structure of the items. This is called expert paneling. Draft items are administered to the panel for ranking and selection based on relevance. Raters may evaluate items on a four-point scale, 4 = highly relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant but needs rewording, and 1 = not relevant. The response of the raters is dichotomized for each item and a content validity index or content validity ratio (CVR) can be calculated. Based on the CVR score, the item may be included or excluded. The items thus selected are administered to a set of respondents (who represent the study population) for face validity. Face validity is a subjective measure which indicates whether, on the face of it, the instrument appears to be assessing the desired qualities.[12]

The draft tool is then pretested. Pretesting is done with members of the target group to assess lack of ambiguity, clarity, and acceptability of the items. Items that do not meet these criteria are reframed or rephrased and pretested again.

ITEM SELECTION AND ITEM REDUCTION

The pretested draft tool is tested for its psychometric properties. The terms “item selection and item reduction” are often used interchangeably. Clinical testing of the draft items involves a piloting and administration on a bigger sample. Initially, a pilot study in a representative sample of 20–30 assesses the test–retest reliability and later with a bigger sample for further testing of other psychometric properties. The data thus obtained can be subjected to statistical testing including factor analysis. The number of items in the draft tool dictates the sample size for factor analysis. Munro et al. recommend five subjects per item while others suggest ten subjects per item for factor analysis.[20] However, the psychometric soundness of the tool lies in the establishment of its reliability and validity through the sequential processes mentioned here.[21]

ESTABLISHING RELIABILITY

Reliability refers to measurement of something in a reproducible manner. It is a measure of repeatability, stability, or internal consistency of a tool. In other words, reliability ensures measurement of individuals on different occasions or by different observers or by similar or parallel tests produce the same or similar results. Before a tool can be employed for a study, it should be established that it is reliable and valid for that particular purpose and its reliability needs to be established before assessing validity. Reliability is expressed as a number between zero and one, with zero indicating no reliability and one indicating perfect reliability. There are three main ways of assessing reliability: internal consistency reliability, inter-/intra-observer reliability, and test–retest reliability.

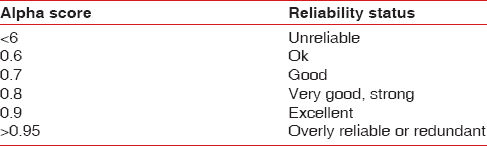

Internal consistency reliability

Internal consistency examines the inter-item correlations within an instrument and indicates how well multiple items combine as a measure of a single concept. In other words, it measures the average of the correlations among all the items in the measure. A low internal consistency means that the items measure different attributes or the subjective responses are inconsistent. Ideally, within a domain, the individual items score similar to each other. If the items are measuring the same underlying concept, then each item should correlate with the total score also. Tests used to measure internal consistency are Cronbach's alpha, Kuder–Richardson 20, or split-halves.[12] Internal consistency ranges from zero to one. Cronbach's alpha should exceed 0.70 for a new tool and 0.80 for a more established tool [Table 1]. Alpha should be determined separately for various domains of the tool which is more important than for the whole tool.

Table 1.

Reliability thumb rule

Test–retest reliability

Test–retest reliability means that the observations on the same patient on two occasions separated by some interval of time are similar. It thus measures the stability of the tool over time. If the patient's clinical condition remains same between two measurements, then scores obtained should be similar. To assess the stability of an instrument over time, the two measurements should be temporally close to each other. Too close, an interval will result in recalling the previous answers rather than giving an independent response. The usual interval between test and retest is between 10 and 14 days. Intraclass correlation coefficient or ICC is the measure of test–retest reliability. In general, ICC values more than 0.7 are accepted as good reliability.

Inter-rater reliability

This form of reliability measure is applicable only in interviewer-administered tools and therefore is not applicable to self-administered tools. Different raters assessing the same individual should obtain similar scores. It is measured with a coefficient between zero and one. Change in a patient's condition such as periodontal disease status between two ratings can be an additional source of error in inter-rater reliability assessment. Inter-rater reliability is expressed as kappa score (Cohen's kappa) if there are two ratters giving dichotomous response and with the intraclass correlation for continuous measures.

Reliability is also defined as the ratio of the variance between people to the total variance of the group. Hence, the reliability of a scale is dependent on the homogeneity of the group; a scale that may be reliable with a heterogeneous group of patients may not be reliable if the group is more homogeneous. Therefore, reliability is not a fixed, immutable property of a test that, once established, is true for all groups. If the reliability of a scale is established with one group but upon use with a different group of people (e.g., more severe cases; patients versus the general population), it is necessary to assess the reliability in that new group also.

ENSURING VALIDITY

While reliability ensures reproducibility and stability of the tool, validity is a process of assessing the degree of confidence; we can place on the inferences made about people based on their scores from a health measurement scale.[12] It guides as to what conclusions can be made about people being investigated using the scale with the obtained score. Even though the discussion of validity is placed after reliability, the virtue of validity is spread over various stages in tool development and is an ongoing process. Content validity and face validity are established in the initial stages of tool development using various subjective and qualitative methods. Validity assessment requires more than peer judgments. There are other empirical forms of validity assessment. The classic expression of a tool's validity pertains to the three Cs of validity; content, criterion, and construct. Currently, all forms of validity are considered as subsets of construct validity.[22]

Criterion validity

To ascertain criterion validity, the tool is compared with an established index or criterion (gold standard) related to what is being measured. It is the correlation of the tool with a gold standard which has been used and accepted in the field for measuring the same attribute. The test should positively correlate with the criterion to have good criterion validity. For example, established periodontal disease should demonstrate CAL. In QoL measure, there is no universally accepted gold standard tool available.[23] Criterion validation can be of two types; concurrent validity – when the new scale and gold standard are administered at the same time and predictive validity – when the criterion will not be available until sometime in the future.

Content validity

Content validity ensures that all aspects of the clinical phenomenon are represented by an adequate number of items and should not include items that are unrelated to the construct. The researcher has to ascertain the content validity of a tool by closely following the item-generation steps mentioned above as there is no strict statistical procedure to ensure it. It can be generalized that the higher the reliability, the higher the maximum possible validity. There is an exception to this when assessing tools that measure a heterogeneous trait. The items need to be heterogeneous to tap the wider content. Since the items are heterogeneous, the internal consistency will be low. Even though deletion of certain items would improve internal consistency, it is better to sacrifice internal consistency by retaining the items, thus ensuring content validity. Since the ultimate aim of the tool is to evaluate, compare, or diagnose clinical states, content validity is more critical than internal consistency.

Construct validity

In case of attributes such as attitudes, beliefs, and feelings, there is no objective criterion available. Content validity too may be insufficient for such attributes. Such situation demands establishing construct validity. Construct validity is a process of hypothesis testing. A hypothesis is formulated and studies are devised to prove the hypothesis. As there are a unlimited number of hypotheses that can be derived from the theory, construct validity would be a continuous process. Construct validation is heavily relied upon in situ ations when there is no criterion with which a tool can be compared. One has to generate predictions based on a hypothetical construct (hypothesis generating) and is tested to give support to it, thereby ensuring construct validity.[24] It is an ongoing process of learning more about the construct, making new predictions, and testing them. It is almost a never-ending evaluation of how the scale performs in a variety of situations. Convergent validity and divergent validity are terms used to distinguish between two aspects of construct validity. Convergent validity seeks whether the measurement is related to variables to which it should be related whereas divergent validity seeks whether the measurement is unrelated to variables to which it should be unrelated. Discriminant validity is the ability of the tool to discriminate between different groups of subjects and quite often used interchangeably with divergent validity. Discriminant validity of a periodontal disease-specific tool ensures that the scores obtained differentiate between periodontal health and disease or between less severe and severe diseases. Convergent validity ensures that the score of the tool is positively correlated with clinical measures of disease such as CAL and bleeding on probing.

Factor analysis is the statistical method used to determine the constructs of a developing tool. Factor analysis completes the item reduction process to get a tool with minimum number of items and maximum variance without compromising the content validity. Validation efforts can be based on different sources such as theory (content validity), logic (face validity), and empirical evidence (construct validity and criterion validity). Therefore, it can be deduced that validation of a scale is a process whereby the researcher determines with some degree of confidence whether the information obtained about people based on the particular scale score is valuable or not.

RESPONSIVENESS AND MINIMALLY IMPORTANT DIFFERENCE

If a disease or any health condition impacts QoL of the sufferer, it should change once the disease is treated or cured or the condition is reversed. Longitudinal studies assess the change in QoL effected by treating the condition. OHRQoL scales are employed to measure this change in QoL, if any, posttreatment. If there is a change in condition following treatment, it should be reflected in the scale score. The quality of the tool to measure subtle changes in the perception of subjects brought about by treatment/cure of disease is known as responsiveness. The empirical testing of pre-/post-treatment QoL score may show statistically significant change, which may not be clinically meaningful.[25] The smallest change in a score that can be perceived as beneficial is known as minimally important difference or MID.[26,27] MID assessment is based on the smallest score or change in score that is likely to be important from the patients' or clinicians' perspective.[27] MID, therefore, is an important parameter for a tool employed in a longitudinal clinical trial to determine whether the observed change in OHRQoL scores after treatment is clinically meaningful.[28]

EXISTING TOOL OR A NEW TOOL – HOW TO DECIDE?

What is the need to develop a new tool to assess subjective psychometric aspects when many tools already exist? This is a sensible question. There are two reasons to look for a new tool. (1) The aspect or attribute of the disease or condition to be studied could be a new one and there exists no scale to measure it. (2) The existing tool is incomplete to measure the attribute that means it requires some modifications. The construct validation approach makes use of the underlying theoretical concepts to develop a new or better instrument which explains the attribute better. The rationale of construct validity here is to assess whether the new tool is shorter, cheaper, or less invasive for the particular purpose when compared to the gold standard.

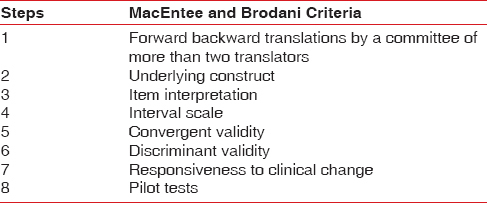

Health-related QoL is strongly dependent on culture and beliefs. QoL being a multidimensional construct having a social dimension; tools developed in one language for a particular population in a particular society may not be valid for others. This is particularly significant for a country like India with so much of diversity in social, cultural, ethnic, economic, and linguistic aspects among various regions. The customs, religious practices, and health beliefs vary considerably as do the literacy and health awareness. Thus, the tools developed for Western populations or others could not be utilized to study the QoL by mere translation into any of the Indian languages. Relevant modifications have to be made in the content and construct of the tool according to the sociodemographic features to assess the subjective perception. However, available tools can be translated into a different language and cross-culturally adapted with the help of linguistic and subject experts. The steps include translation of the tool by a team of bilingual experts, back translation, and derivation of the best version by consensus. Translation should not be done technically on a word to word basis, but the cultural context should be addressed to ensure conceptual equivalence. MacEntee and Brodani suggested eight steps to ensure translational validity [Table 2]. The time and effort needed for the process is almost similar to new tool development.[29]

Table 2.

Eight steps in translational validity

CONCLUSION

Existing literature suggests that periodontal disease does have an impact on individual's QoL; hence, the relevance of measuring it is justified. The recent increase in number of research publications that deal with OHRQoL will support this fact. It is difficult to enumerate the sequential steps in developing a new tool and segregate the psychometric properties of a tool into watertight compartments as there is difference in the chronological order in which they are ensured and clinically studied. It has to be reproducible and particularly valid to the context of use. The steps involved are complicated and time-consuming. The use of existing tool, if it fulfills your research question, is recommended after cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric testing. Assessment of patient's perceived change following the treatment of disease may become mandatory in future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen PE, Ogawa H. Strengthening the prevention of periodontal disease: The WHO approach. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2187–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.12.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hujoel PP, Drangsholt M, Spiekerman C, DeRouen TA. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease risk. JAMA. 2000;284:1406–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.11.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soskolne WA, Klinger A. The relationship between periodontal diseases and diabetes: An overview. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:91–8. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locker D. Measuring oral health: A conceptual framework. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen LK, Jago JD. Toward the formulation of sociodental indicators. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:681–98. doi: 10.2190/LE7A-UGBW-J3NR-Q992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonetti MS, Fourmousis I, Suvan J, Cortellini P, Brägger U, Lang NP. European Research Group on Periodontology (ERGOPERIO). Healing, post-operative morbidity and patient perception of outcomes following regenerative therapy of deep intrabony defects. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:1092–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen PF. Assessment of oral health related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:40. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson WM, Mejia GC, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. Construct validity of Locker's global oral health item. J Dent Res. 2012;91:1038–42. doi: 10.1177/0022034512460676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawal FB. Global self-rating of oral health as summary tool for oral health evaluation in low-resource settings. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5(Suppl 1):S1–6. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.156516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rattray J, Jones MC. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anastai A, Urbina S. Psychological Testing. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams A. How to write and analyse a questionnaire. J Orthod. 2003;30:245–52. doi: 10.1093/ortho/30.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roopa S, Rani MS. Questionnaire designing for a survey. J Indian Orthod Soc. 2012;46:273–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, Ernst DM, Hayden SJ, Lazzara DJ, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:155–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musurlieva N, Stoykova M, Boyadjiev D. Validation of a scale assessing the impact of periodontal disease on patients quality of life in Bulgaria (Pilot research) Braz Dent J. 2012;23:570–4. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402012000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munro BH. Statistical Methods for Health Care Research. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowling A. Research Methods in Health. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landy FJ. Stamp collecting versus science: Validation as hypothesis testing. Am Psychol. 1986;74:1183–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotecha S, Turner PJ, Dietrich T, Dhopatkar A. The impact of tooth agenesis on oral health-related quality of life in children. J Orthod. 2013;40:122–9. doi: 10.1179/1465313312Y.0000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull. 1955;52:281–302. doi: 10.1037/h0040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oates TW, Robinson M, Gunsolley JC. Surgical therapies for the treatment of gingival recession. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:303–20. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyrwich KW, Norquist JM, Lenderking WR, Acaster S. Industry Advisory Committee of International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL). Methods for interpreting change over time in patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:475–83. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jönsson B, Öhrn K. Evaluation of the effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on oral health-related quality of life: Estimation of minimal important differences 1 year after treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:275–82. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacEntee MI, Brondani M. Cross-cultural equivalence in translations of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:109–18. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]