Abstract

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a disease characterized by inflammation of pancreatic islets associated with autoimmunity against insulin-producing beta cells, leading to their progressive destruction. The condition constitutes a significant and worldwide problem to human health, particularly because of its rapid, but thus far unexplained, increase in incidence. Environmental factors such as viral infections are thought to account for this trend. While there is no lack of reports associating viral infections to T1D, it has proven difficult to establish which immunological processes link viral infections to disease onset or progression. One of the commonly discussed pathways is molecular mimicry, a mechanism that encompasses cross-reactive immunity against epitopes shared between viruses and beta cells. In this review, we will take a closer look at the mechanistic evidence for a potential role of viruses in T1D, with a special focus on molecular mimicry.

INTRODUCTION

Insulin secretion from the pancreatic beta cells is essential for the body’s ability to maintain glucose homeostasis. In the pancreas of subjects with T1D, beta cells are targeted by inflammation also containing autoreactive T cells, resulting in their destruction and ultimately the loss of insulin secretion. As a consequence, the patient becomes dependent on exogenous insulin administration, and has an increased risk for developing cardiovascular and neurological complications.

Genetics significantly contribute to T1D risk, but cannot explain the incomplete concordance rates among monozygotic twins (1–3). Even if it is assumed that concordance rates are higher than previously thought, the significant temporal divergence in clinical onset between twins suggests the involvement of additional variables (4). Such evidence indirectly implies a role for environmental factors in the disease etiology. Further supporting this notion is the recent and substantial increase in T1D incidence, often among children younger than 5 years of age (5). This rise started in the 1950s and hence is too sudden to be explainable by altered population genetics.

Vitamin D, bacteria, wheat proteins, and cow’s milk have all been investigated with regards to T1D, but the strongest associations have been found with viral infections, particularly with enteroviruses (6). However, the situation is by no means completely clear and a recent report, for example, has found no association between the presence of enteroviruses in stool and the development of diabetes in children (7). At present, it is unknown whether viruses can only accelerate ongoing autoimmunity, as suggested by some experimental models (8, 9), or whether they can actually initiate the entire autoimmune process. In addition, there is evidence from animal studies that systemic viral infections of lower pathogenicity can actually be beneficial and prevent T1D in certain scenarios (10, 11). It should also be kept in mind that the mechanistic hypotheses linking viruses to T1D, as discussed below, are almost entirely based on studies in animal models.

GENE-VIRUS INTERPLAYS?

So far, more than 40 susceptibility genes have been found to influence T1D risk. These include many loci containing genes involved in immunity such as PTPN22, CTLA4, and IL2RA. The major genetic risk (30–50%) is, however, linked to the HLA class II loci, where the haplotype HLA-DR3 or DR-4 confers the greatest risk (12).

With the advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), the list of T1D susceptibility genes has dramatically grown, and it is now apparent that the condition is polygenic and is likely caused by different combinations of polymorphisms across patients (13). It thus seems rather unlikely that targeting just one specific signaling pathway will be sufficient to achieve therapeutic benefit in all patients, and it is still uncertain how our improved knowledge on the genetics of T1D will translate to more rational drug design. On the other hand, interesting new genes were discovered that expose possible mechanisms that may link viruses to T1D.

One of the T1D risk genes that has been discovered is IFIH1 (14). IFIH1 codes for a helicase involved in recognition of viral dsRNA and is important for type 1 interferon production in response to e.g. Coxsackievirus infection, a virus that has been linked to T1D. A functionally altered form of the IFIH1 gene product could be envisioned to trigger an exaggerated response to virus infection. This could in turn result in the establishment of a local inflammatory milieu, for instance in the pancreas, and eventually an aberrant immune response against beta cells. This hypothesis became even more enticing with the identification of rare IFIH1 variants that protect against T1D (15). The latter finding suggests that certain IFIH1 polymorphisms may confer hyporesponsiveness to viruses and may be associated with decreased risk for developing autoimmune inflammation. Collectively, these data were heralded as prime examples of how environmental factors such as viruses may act in concert with genetic constitution of the host to culminate in autoimmune disease.

PATHWAYS TOWARD VIRUS-INDUCED BETA CELL DECAY

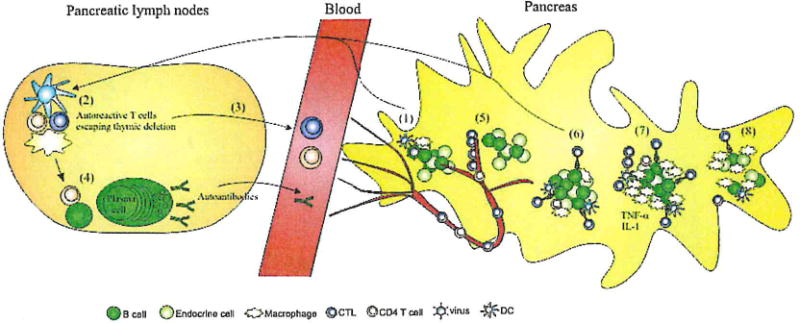

Immune mechanisms commonly proposed to link viruses to T1D pathogenesis include perturbation of thymic T cell education, beta cell-specific infection, bystander activation and molecular mimicry (Fig. 1). We will briefly touch on the former three while elaborating more on current support for viral mimicry.

Fig. 1.

A model for the development of T1D. (1) An unknown environmental agent, possibly a virus, triggers uptake and drainage of islet antigens. The virus may or may not infect beta cells directly as depicted, establish a local inflammatory milieu, or may act by directly activating T cells via molecular mimicry. (2) In susceptible individuals, autoreactive T cells recognize these antigens and become activated, resulting in (3) T cell release into the circulation and (4) B cell activation. (5) T cell effectors subsequently extravasate in the pancreas and M (6) recognize their targets, the beta cells, leading to ‘antigen spreading’ and (7) influx of new autoreactive T cell species. T cells attract innate cells such as macrophages during this progressed stage, which produce cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. (8) Ultimately, most beta cells are destroyed and hyperglycemia develops.

Perturbation of thymic T cell education

A theory that has attracted some attention entails that viral infections may interfere with T cell selection in the thymus. Coxsackie B4 virus, a highly diabetogenic member of the enterovirus genus, was found to infect the thymus of experimentally infected mice and to profoundly affect T cell maturation (16). In vitro data also indicate that Coxsackie B4 virus has the ability to infect human thymocytes (17). It is, however, uncertain whether these experimental data bear any relevance to the natural course of T1D. There are no reports of similarly gross abnormalities in the general T cell repertoire prior to or around clinical onset, and even the claim that Treg numbers are decreased in T1D patients was recently challenged (18). In any case, a disturbing role for viruses in thymic selection will most likely be of subtle nature and therefore extremely difficult to prove in a human setting.

Viral infection of beta cells

The ability to infect beta cells has been demonstrated for several viruses, including enteroviruses (19–21). However, although cytolytic effects in isolated human islets have been shown, direct support for cytolytic viral infection as a major cause of beta cell death in vivo is lacking. Indeed, the lack of widespread beta cell apoptosis in histological pancreas samples from recently diagnosed diabetics speaks against beta cell-specific infection as a common cause (22). However, direct beta cell infection might trigger ‘fulminant diabetes’, a subtype of T1D with a rapid course where patients commonly present with infectious symptoms (23, 24). It is doubtful, however, how this acute condition relates to classical T1D and whether it has an autoimmune component at all.

An alternative theory would be that some virus is capable of silently persisting within pancreatic islets. Persistence of enterovirus in humans as well as in animals has been demonstrated (25), suggesting a possible role in T1D etiology. Moreover, it is commonly observed that islet cells from recently diagnosed T1D subjects overexpress MHC class I, interferon alpha and other immune markers that are typically associated with viral infection (26). While to date no study has unequivocally correlated these events with the local presence of viruses, these findings suggest that as yet undefined viral strains may silently persist within pancreatic islets. However, we were unable to provide evidence of ongoing viral infection in longstanding T1D pancreas sections obtained via the network for Pancreatic Organ donors with Diabetes (nPOD) that displayed pronounced upregulation of MHC class I (unpublished data). Moreover, it has never been seen that enteroviruses can persist for more than 3–4 months maximally, although a recent report has challenged this notion for polioviruses (27).

Bystander activation

Bystander activation instead implies a more nonspecific role for viruses in inducing autoimmune T cell responses against beta cells. Here, viruses act by establishing an inflammatory microenvironment by triggering the production of soluble factors such as cytokines and chemokines. Naïve autoreactive T cells that have escaped thymic selection in susceptible individuals may subsequently become activated in a non-antigen specific fashion. Alternatively, the generation of a pro-inflammatory milieu may exert its effect indirectly via antigen-presenting cells, which in turn activate certain autoreactive T cell species (28). Finally, T cells that are not specific for islet antigens may also become attracted and activated by the local cytokine milieu and may in turn contribute to disease progression by additional release of soluble factors, creating a vicious cycle of beta cell destruction. Recently, the contribution of the latter pathway has been questioned based on results in animals finding that in fact all T cells that access the islets are specific for islet antigens (29).

Molecular mimicry

Molecular mimicry proposes the activation of auto-aggressive T cells in T1D as the result of a virus carrying an epitope that strongly resembles certain structures on the beta cells, and which consequently induces a cross-reactive autoimmune response that eliminates not only the infecting virus but also the body’s pancreatic beta cells (30). We will further discuss arguments in favor or opposing such a pathway below.

EVIDENCE FOR MOLECULAR MIMICRY IN AUTOIMMUNITY AND T1D?

From a conceptual viewpoint, we argue that molecular mimicry is not an unlikely scenario to occur in general, but that it is less likely that it would precipitate autoimmune diabetes in a healthy individual. Let us consider, as argued before by Mason, that each T cell must have the ability to productively react with up to a million of similar, but different peptides to account for a fully protective T cell repertoire (31). If each T cell would recognize only a single peptide, our adaptive immune system would simply not be able to deal with the vast variety of antigenic determinants it encounters on a daily basis. Thus, if we assume that cross-reactivity is an intrinsic and necessary characteristic of the degenerate T cell repertoire, it would not be surprising that some T cells at some point will also recognize self-anti-gens (32). The balance between autoimmunity and tolerance as an outcome may then be mediated by factors such as T cell avidity and/or reactive T cell numbers. In other words, under conditions of ‘bad luck’, i.e. when a T cell encounters the right antigen at the right time and under specific conditions, cross-reactivity may lead to autoimmunity.

In some autoimmune conditions other than T1D, immune cross-reactivity due to homology between pathogens and self-epitopes was demonstrated (33). Rheumatic fever, for instance, is now recognized as a post-infectious autoimmune disease that affects genetically susceptible children following infection with group A streptococci. The most serious complication is rheumatic heart disease, where T cell infiltration causes inflammatory heart lesions. Shared epitopes have been found between streptococcal antigens and proteins on various human tissues involved in the disease, thereby providing strong arguments favoring molecular mimicry.

Another example may be Guillain Barré syndrome, a peripheral neuropathy associated with Campylobacter jejuni infection. The pathogen shares structural homology with the peripheral nerve GM1 ganglioside and causality could be convincingly reproduced in an animal model (34). Less definite proof for molecular mimicry has also been gathered in immune diseases connected to the HLA allele B27, such as ankylosing spondyloarthritis. Several Gram-negative bacteria, e.g. Klebsiella pneumonia, carry epitopes with homology to the HLA-B27 protein and infections with some of these microorganisms are indeed associated with clinical onset (35).

Cross-reactivity that leads to autoimmunity is not necessarily limited to infectious agents as exemplified by halothane hepatitis, a rare condition of hepatic injury which occurs in 1/3000 people when exposed to the anesthetic drug halothane (9). In these subjects, antibodies are raised against the protein-bound metabolite trifouroacetylated (TFA). These antibodies cross-react with an epitope on the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) and thereby cause liver necrosis.

In T1D, research focusing on Coxsackievirus as the environmental trigger found potential cross-reactivity between the non-structural protein 2C viral protease and the human antigen GAD65, a common target for auto-anti-bodies and T cells in T1D (36). It was later shown, however, that the homology between these two epitopes was not associated with significant functional consequences (37). Sequence similarities were also identified between GAD65 and cytomegalovirus, and corresponding viral peptides were recognized by GAD65-reactive T cell clones (38). Analogously, the islet antigen tyrosine phosphatase (IA-2) carries sequences similar to those found in enteroviruses and it was found that enterovirus infection can induce cross-reactive immune responses (39). As a final example, it was recently found that molecular mimicry with rotavirus could promote autoimmunity to certain islet antigens (40).

From these data, one can conclude that evidence for viral mimicry in human T1D is existing, based on the identification of sequence correspondences and in vitro reactivity profiling, but proof for its role in disease pathogenesis is relatively limited and for obvious logistic and ethical reasons. More functional support for a causal role has therefore come from animal models.

LESSONS FROM THE RIP-LCMV MOUSE MODEL

The RIP-LCMV mouse is a model for T1D developed in parallel by two laboratories in 1991 (41, 42), where beta cell destruction is induced through infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). The first phase of the host’s immune response is directed against the virus and complete viral clearance is normally achieved around day seven after infection. The recipient mice, however, have been transgenically designed to express an LCMV protein within their beta cell compartment. Thus, T cells that were initially raised against LCMV will, upon viral clearance, direct their cytotoxic action against the beta cells, leading to demise of the latter and consequential onset of clinical hyperglycemia. This model offered proof-of-principle that direct reactivity between a viral and a non-tolerant self-antigen can lead to the generation of an autoimmune response against other beta cell antigens to which the host system is normally tolerant (43).

The original RIP-LCMV model obviously has the limitation that the viral protein expressed by beta cells shows no difference in sequence to the self-protein, and as such is not representative of molecular mimicry as it is envisioned to occur in humans. However, follow-up studies in this model used a viral (LCMV) variant that had a mutation in the disease-inducing CD8 epitope and thus constituted a true molecular mimic of the viral (self)-protein expressed in beta cells (44). In these mice infection with the LCMV, Pasteur strain was unable to precipitate any diabetes, clearly demonstrating that it is difficult if not impossible to precipitate autoimmune diabetes in otherwise healthy animals. Thus, mimicry, unless there were to be very strong cross-reactivity, is unlikely to cause autoimmune diabetes. In addition, if complete homology or very strong cross-reactivity between certain viruses and islet antigens were at the basis of T1D development in humans, one would expect a more acute disease phenotype as in the RIP-LCMV model, which is not the case. It is therefore hypothesized that similarities rather than exact sequence homologies between viral and self-epitopes may lead to more subtle, chronic autoimmune responses against beta cells (45). Studies in the RIP-LCMV system suggested that complete sequence identity is required to initiate diabetes as single amino acid changes in the viral-epitope on (3-cells protected these mice from diabetes (44). Nevertheless, molecular mimicry has been shown to accelerate disease progression in the context of virally induced pancreatic inflammation, suggesting that sequence homologies may not be the initiating trigger in T1D, but are capable of codetermining the pace by which disease develops (8, 9). In conclusion, the theory that mimicry could act as a disease accelerator, but not precipitator is attractive based on animal data but hard-to-prove in human T1D.

WHAT CAN ALTERED PEPTIDE LIGANDS TEACH US?

In immunology, altered peptide ligands (APLs) are peptides that closely resemble other peptides that are known to activate certain T cell clones. Starting from the amino acid sequence of a known peptide of interest, APL is designed by targeted substitutions in the T cell receptor contact site (46). As a result, T cell activation in response to APL is usually altered as compared with the original peptide. A first (unsuccessful) phase II clinical trial in T1D was aimed at inducing tolerance against insulin via administration of an APL ligand (47). Usually developed for therapeutic purposes, APLs have provided insight into how binding avidity between TCR, MCH molecule, and peptide affect T cell responses. APLs are able to induce altered T cell signaling with responses such as complete, partial, or repealed activation as well as T cell anergy. In analogy with APLs, peptides relevant in the context of molecular mimicry may have the capacity to induce numerous different T cell responses, making their impact difficult to predict. In other words, APL constitutes a labdesigned, testable concept that may epitomize molecular mimicry as it occurs in living organisms.

TIMING OF A PUTATIVE VIRAL MIMICRY EVENT

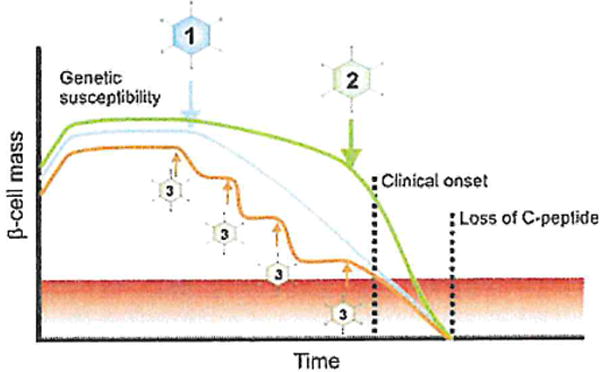

In 1986, Eisenbarth proposed that the decline of beta cells in T1D is a linear process that may take years of subclinical islet inflammation until it culminates in hyperglycemia [(48); Fig. 2], One of the outstanding questions is when, along this time line, viruses come into play? It is still uncertain whether viral infections are able to initiate islet autoimmunity or rather act as accelerators of an ongoing immune process. The fertile field hypothesis argues that a transient viral infection of the pancreas is required to establish suitable conditions in which islet antigens are released and presented to autoreactive T cells (49). Thus, this theory attributes a role to viruses as primary initiators of autoimmunity, at the very beginning of beta cell decay. The emergence of a full repertoire of islet-specific T cell species would then be a secondary event related to ‘epitope spreading’, i.e. the gradual expansion of the reactivity profile under inflammatory conditions. Experimental data in the NOD mouse, however, appear to contradict this model and suggest that islet inflammation is in fact the pre-conditioning parameter (50, 51). Here, viral infection would simply be the straw to break the camel’s back when superimposed onto the local inflammatory islet milieu. Based on these observations, viral infections are positioned at the right end of the Eisenbarth model, around clinical diagnosis, and may be accompanied by a deviation from linear beta cell decay. Indirect clinical data exist to support both models (52, 53). An alternative mechanism is that multiple viral infections, in a hit-and-run fashion, over the course of many years ultimately result in disease onset. These considerations collectively indicate that a definite association of viral mimicry events with clinical disease is a cumbersome task.

Fig. 2.

Possible timing of infectious events during the natural course of T1D. (1) The linear model proposed by Eisenbarth assumed the involvement of an environmental trigger, followed by a linear decline in beta cell mass. (2) An alternative scenario would imply the presence of low-grade, subclinical inflammation that is rapidly enhanced by an infectious agent around the time of onset. Beta cell decay is consequentially aggravated and enters an exponential decline. (3) Multiple infectious stages may act in concert in a hit-and-run fashion, ultimately driving most beta cells into apoptosis. Note that none of the pathways described here are mutually exclusive.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The concept of molecular mimicry in T1D is well tested in animal models, which demonstrate that cross-reactivities could potentially accelerate an ongoing disease process rather than precipitating autoimmunity in naive individuals. On the other hand, support in a human setting remains fragmentary. One of the difficulties is of course the inaccessibility of the target organ, which impedes longitudinal association studies. Research in human is therefore generally performed on postmortem specimens, which only provide a snapshot of the pathological process. There are now reasonably conclusive grounds to assume that viruses are associated with the natural course of T1D in at least a fraction of patients (6). How exactly viral infections mediate immune responses against beta cells is uncertain, but theoretical considerations on potential cross-reactivity within a degenerate T cell repertoire indicate that molecular mimicry might be a possibility. To functionally test the mechanism of molecular mimicry, one would have to experimentally induce T cells with a viral peptide mimic that resembles a defined islet epitope, which is exactly the type of approach that will always need to be performed in an animal setting. Finally, future clinical studies with altered peptide ligands may prove instrumental in shedding more light on the mechanisms governing T cell cross-reactivity to self-antigens.

References

- 1.Barnett AH, Eff C, Leslie RD, Pyke DA. Diabetes in identical twins. A study of 200 pairs. Diabetologia. 1981;20:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00262007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo SS, Tun RY, Hawa M, Leslie RD. Studies of diabetic twins. Diabetes Metabo Rev. 1991;7:223–38. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redondo MJ, Yu L, Hawa M, Mackenzie T, Pyke DA, Eisenbarth GS, et al. Heterogeneity of type I diabetes: analysis of monozygotic twins in Great Britain and the United States. Diabetologia. 2001;44:354–62. doi: 10.1007/s001250051626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redondo MJ, Jeffrey J, Fain PR, Eisenbarth GS, Orban T. Concordance for islet autoimmunity among monozygotic twins. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2849–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung WC, Rawlinson WD, Craig ME. Enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational molecular studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d35. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonen-Tikka ML, Pflueger M, Klemola P, Savolainen-Kopra C, Smura T, Hummel S, et al. Human enterovirus infections in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes: the Babydiet study. Diabetologia. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christen U, Edelmann KH, McGavern DB, Wolfe T, Coon B, Teague MK, et al. A viral epitope that mimics a self antigen can accelerate but not initiate autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1290–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI22557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christen U, Quinn J, Yeaman SJ, Kenna JG, Clarke JB, Gandolfi AJ, et al. Identification of the dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase subunit of the human pyruvate dehydrogenase complex as an autoantigen in halothane hepatitis. Molecular mimicry of trifluoroacetyl-lysine by lipoic acid. Eur J Biochem. 1994;223:1035–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filippi CM, Estes EA, Oldham JE, von Herrath MG. Immunoregulatory mechanisms triggered by viral infections protect from type 1 diabetes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1515–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI38503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tracy S, Drescher KM, Chapman NM, Kim ICS, Carson SD, Pirruccello S, et al. Toward testing the hypothesis that group B coxsackieviruses (CVB) trigger insulin-dependent diabetes: inoculating nonobese diabetic mice with CVB markedly lowers diabetes incidence. J Virol. 2002;76:12097–111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12097-12111.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Concannon P, Rich SS, Nepom GT. Genetics of type 1A diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1646–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steck AK, Rewers MJ. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Clin Chem. 2011;57:176–85. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.148221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smyth DJ, Cooper JD, Bailey R, Field S, Burren O, Smink LJ, et al. A genome-wide association study of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a type 1 diabetes locus in the interferon-induced helicase (IFIH1) region. Nat Genet. 2006;38:617–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nejentsev S, Walker N, Riches D, Egholm M, Todd JA. Rare variants of IFIH1, a gene implicated in antiviral responses, protect against type 1 diabetes. Science. 2009;324:387–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1167728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee NK, Hou J, Dockcstader P, Charbonneau T. Coxsackievirus B4 infection alters thymic, splenic, and peripheral lymphocyte repertoire preceding onset of hyperglycemia in mice. J Med Virol. 1992;38:124–31. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890380210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brilot F, Geenen V, Hober D, Stoddart CA. Coxsackievirus B4 infection of human fetal thymus cells. J Virol. 2004;78:9854–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9854-9861.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brusko T, Wasserfall C, McGrail K, Schatz R, Viener HL, Schatz D, et al. No alterations in the frequency of FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:604–12. doi: 10.2337/db06-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren AG, Marselli L, Masini M, Dionisi S, et al. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of beta cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5115–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elshebani A, Olsson A, Westman J, Tuvemo T, Korsgren O, Frisk G. Effects on isolated human pancreatic islet cells after infection with strains of enterovirus isolated at clinical presentation of type 1 diabetes. Virus Res. 2007;124:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vpl immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1143–51. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler AE, Galasso R, Meier JJ, Basu R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Modestly increased beta cell apoptosis but no increased beta cell replication in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients who died of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2323–31. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imagawa A, Hanafusa T, Miyagawa J, Matsuza wa Y. A novel subtype of type 1 diabetes mellitus characterized by a rapid onset and an absence of diabetes-related antibodies. Osaka IDDM Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:301–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka S, Nishida Y, Aida K, Maruyama T, Shimada A, Suzuki M, et al. Enterovirus infection, CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and CXCR3 circuit: a mechanism of accelerated beta-cell failure in fulminant type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:2285–91. doi: 10.2337/db09-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman NM, Kim ICS. Persistent coxsackievirus infection: enterovirus persistence in chronic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;323:275–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75546-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulis AK, Farquharson MA, Meager A. Immunoreactive alpha-interferon in insulin-secreting beta cells in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1987;2:1423–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeVries AS, Harper J, Murray A, Lexau C, Bahta L, Christensen J, et al. Vaccine-derived poliomyelitis 12 years after infection in Minnesota. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2316–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwitz MS, Ilic A, Fine C, Rodriguez E, Sarvetnick N. Presented antigen from damaged pancreatic beta cells activates autoreactive T cells in virus-mediated autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:79–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI11198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lennon GP, Bettini M, Burton AR, Vincent E, Arnold PY, Santamaria P, et al. T cell islet accumulation in type 1 diabetes is a tightly regulated, cell-autonomous event. Immunity. 2009;31:643–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB. Molecular mimicry as a mechanism for virus-induced autoimmunity. Immunol Res. 1989;8:3–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02918552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason D. A very high level of crossreactivity is an essential feature of the T-cell receptor. Immunol Today. 1998;19:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benoist C, Mathis D. Autoimmunity provoked by infection: how good is the case for T cell epitope mimicry? Nat Immunol. 2001;2:797–801. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guilherme L, Kalil J. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: cellular mechanisms leading autoimmune reactivity and disease. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ang CW, Jacobs BC, Laman JD. The Guillain-Barre syndrome: a true case of molecular mimicry. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwimmbeck PL, Yu DT, Oldstone MB. Autoantibodies to HLA B27 in the sera of HLA B27 patients with ankylosing spondylitis and Reiter’s syndrome. Molecular mimicry with Klebsiella pneumoniae as potential mechanism of autoimmune disease J Exp Med. 1987;166:173–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson MA, Bowman MA, Campbell L, Darrow BL, Kaufman DL, Maclaren NIC. Cellular immunity to a determinant common to glutamate decarboxylase and coxsackie virus in insulin-dependent diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2125–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI117567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schloot NC, Willemen SJ, Duinkerken G, Drijfhout JW, de Vries RR, Roep BO. Molecular mimicry in type 1 diabetes mellitus revisited: T-cell clones to GAD65 peptides with sequence homology to Coxsackie or proinsulin peptides do not crossreact with homologous counterpart. Human immunol. 2001;62:299–309. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiemstra HS, Schloot NC, van Veelen PA, Willemen SJ, Franken ICL, van Rood JJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus in autoimmunity: T cell crossreactivity to viral antigen and autoantigen glutamic acid decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3988–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071050898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harkonen T, Lankinen H, Davydova B, Hovi T, Roivainen M. Enterovirus infection can induce immune responses that cross-react with beta-cell autoantigen tyrosine phosphatase IA-2/IAR. J Med Virol. 2002;66:340–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Honeyman MC, Stone NL, Falk BA, Nepom G, Harrison LC. Evidence for molecular mimicry between human T cell epitopes in rotavirus and pancreatic islet autoantigens. J Immunol. 2010;184:2204–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, Pircher H, Ohashi CT, Odermatt B, et al. Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305–17. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell. 1991;65:319–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holz A, Dyrberg T, Hagopian W, Homann D, von Herrath M, Oldstone MB. Neither B lymphocytes nor antibodies directed against self antigens of the islets of Langerhans are required for development of virus-induced autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2000;165:5945–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sevilla N, Homann D, von Herrath M, Rodriguez F, Harkins S, Whitton JL, et al. Virus-induced diabetes in a transgenic model: role of cross-reacting viruses and quantitation of effector T cells needed to cause disease. J Virol. 2000;74:3284–92. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3284-3292.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christen U, von Herrath MG. Induction, acceleration or prevention of autoimmunity by molecular mimicry. Mol Immunol. 2004b;40:l 113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM. Altered peptide ligand-induced partial T cell activation: molecular mechanisms and role in T cell biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter M, Philotheou A, Bonnici F, Ziegler AG, Jimenez R. No effect of the altered peptide ligand NBI-6024 on beta-cell residual function and insulin needs in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2036–40. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisenbarth GS. Type I diabetes mellitus. A chronic autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1360–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605223142106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Herrath MG, Fujinami RS, Whitton JL. Microorganisms and autoimmunity: making the barren field fertile? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:151–7. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drescher KM, Kono K, Bopegamage S, Carson SD, Tracy S. Coxsackievirus B3 infection and type 1 diabetes development in NOD mice: insulitis determines susceptibility of pancreatic islets to virus infection. Virology. 2004;329:381–94. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serreze DV, Ottendorfer EW, Ellis TM, Gauntt CJ, Atkinson MA. Acceleration of type 1 diabetes by a coxsackievirus infection requires a preexisting critical mass of autoreactive T-cells in pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2000;49:708–11. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oikarinen S, Martiskainen M, Tauriainen S, Huhtala H, Ilonen J, Veijola R, et al. Enterovirus RNA in blood is linked to the development of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:276–9. doi: 10.2337/db10-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stene LC, Oikarinen S, Hyoty H, Barriga KJ, Norris JM, Klingensmith G, et al. Enterovirus infection and progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes and Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) Diabetes. 2010;59:3174–80. doi: 10.2337/db10-0866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]