Abstract

The enterovirus 71 (EV71) SP70 epitope, derived from amino acids 208–222 of VP1, is a neutralizing epitope. The present study aimed to assess the inter-species differences of the antibodies induced by EV71-based antigens in responses to SP70 mutant peptides. BALB/c mice and Lou/C rats were immunized with EV71 SP70. Monoclonal antibodies (Mabs) were produced by hybridoma clones. Serum polyclonal antibodies (Pabs) were produced from BALB/c mice and New Zealand white rabbits immunized with recombinant EV71 VP1 (rEV71-VP1) protein or inactivated EV71. Micro-neutralization and immunofluorescence assays were used to evaluate the capacity of the antibodies to bind to EV71. Reactivity of Mabs and Pabs to mutated SP70 were determined by alanine scanning mutagenesis. Furthermore, serums from EV71-infected patients were collected to examine the affinity of SP70 antibody in the serum to mutated SP70, using competitive ELISA. The binding affinity of mouse Mabs to the SP70 epitope was increased by alanine substitution at sites of 210, 212, 213, 214, and 221. The binding affinity of rat Mabs to the SP70 epitope was increased by alanine substitution at sites 210, 217, 219, and 221. Mouse serum Pabs elicited by inactivated EV71 bound wild-type SP70, but lost affinity for mutated peptides. Conversely, rabbit serum Pabs elicited by inactivated EV71 robustly recognized SP70 mutants. Mouse serum Pabs elicited by rEV71-VP1 presented the same trend as mouse Mabs. Mutations at sites 214, 215, and 217 led to loss of recognition by rabbit Pabs elicited by rEV71-VP1, while most mutations did not influence antibody binding. Compared with the wild-type, mutations at the sites 209, 219 and 221 of SP70 lead to increased affinity with the serum antibodies produced by the EV71-infected patients. Antibody responses triggered by inactivated EV71, rEV71-VP1 and EV71 SP70 differed among species in neutralizing capacity and affinity for SP70 mutant peptides.

Keywords: hand, foot and mouth disease, enterovirus 71, SP71 epitope, alanine scanning, antibody affinity

Introduction

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is characterized by the development of mild febrile illness with papulovesicular lesions on the hands, feet, and mouth. HFMD outbreaks have been reported throughout the Asia-Pacific region and pose a serious health threat to young children (1). Epidemics of HFMD in China recently became an important public health concern and 1,898,760 cases of HFMD have been reported in 2015 alone (2–5). Enterovirus 71 (EV71) is the main causative agent of HFMD and is responsible for the majority of deaths in children under 3 years of age (6,7). The primary manifestations of deadly EV17 infection is brain stem encephalitis, pulmonary edema, and heart failure (5,8,9).

EV71 is a small non-enveloped virus composed of a single positive-strand RNA enclosed in an icosahedral capsid assembled with four structural proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4) (10). VP1, VP2, and VP3 are exposed on the surface of the virion, while VP4 is hidden inside (11). VP1 is a promising target for the development of vaccines as it is reported to elicit neutralizing antibody responses. Foo et al recently reported that the highly conserved SP70 peptide derived from amino acids (aa) 208–222 of VP1 (YPTFGEHKQEKDLEYC) can elicit neutralizing antibodies in mice (12,13). This response was comparable to the neutralizing antibody response elicited by whole virion, and primarily involved IgG1 (14,15).

Nevertheless, the mechanisms by which SP70-directed antibodies neutralize EV71 are not yet understood. In this study, we synthesized a set of SP70 mutated peptides using alanine scanning mutagenesis. These peptides were used to characterize species-specific antibodies induced by EV71-based antigens.

Materials and methods

Cells and virus

Vero cells and myeloma SP2/0 and YB2/0 cells [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA, USA] were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

The EV71 strain H3-TY (Genbank no. GU129025.1) was provided by Zhejiang Pukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). EV71 H3-TY is a subtype C4 virus and was isolated from a child with HFMD in Hangzhou (Zhejiang, China). Viral stocks were prepared in Vero cells. Virus titers were determined using the REED-Muench method.

Animals

BALB/c mice (8-week-old, female, n=9), Lou/C rats (3-week-old, female, n=3), and New Zealand white rabbits (2.5–3 kg, female, n=6) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Science (Hangzhou, China). All procedures and animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Science.

Peptide synthesis

The SP70 epitope of EV71 VP1 (aa 208–222) was synthesized, along with 15 similar peptides in which one alanine was substituted for another aa at each position (Table I). The coxsackievirus A16 VP1 epitope (aa 208–222) was synthesized as a negative control (Table I). A keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)-conjugated EV71 SP70 peptide was synthesized. All peptides were synthesized with 95% HPLC purity grade by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) and confirmed by mass spectrometry. The peptides were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 2 mg/ml and stored at −80°C.

Table I.

Sequences of synthesized peptides.

| No. | Peptide sequence |

|---|---|

| WT | YPTFGEHKQEKDLEY |

| 1 | APTFGEHKQEKDLEY |

| 2 | YATFGEHKQEKDLEY |

| 3 | YPAFGEHKQEKDLEY |

| 4 | YPTAGEHKQEKDLEY |

| 5 | YPTFAEHKQEKDLEY |

| 6 | YPTFGAHKQEKDLEY |

| 7 | YPTFGEAKQEKDLEY |

| 8 | YPTFGEHAQEKDLEY |

| 9 | YPTFGEHKAEKDLEY |

| 10 | YPTFGEHKQAKDLEY |

| 11 | YPTFGEHKQEADLEY |

| 12 | YPTFGEHKQEKALEY |

| 13 | YPTFGEHKQEKDAEY |

| 14 | YPTFGEHKQEKDLAY |

| 15 | YPTFGEHKQEKDLEA |

| NC | YPTFGEHLQANDLDY |

Production of purified inactivated EV71 from Vero cells

Vero cells were transduced with the EV71 H3-TY virus, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min, and inactivated by incubation with 0.025% formalin at 37°C for 48 h. After inactivation, the virus was concentrated 100 folds using Pellicon ultrafiltration (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and purified on a sepharose 6-FF column (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Virus concentration was determined by sandwich ELISA (AbMax Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Production of recombinant EV71 VP1 (rEV71-VP1) protein

A recombinant pET32a plasmid (Novagen; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) containing a N-terminal His-tagged EV71 VP1 gene (Genbank no. GU129025.1) was constructed using NdeI and XhoI restriction endonucleases. The plasmid pET32a-EV71 VP1 was transformed into BL21 (DE3) chemically competent cells. Transformed cells were incubated in a shaker at 37°C until their optical density (OD)600 reached 0.6. They were then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) at 37°C for 6 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellet was re-suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0). After ultrasound treatment, inclusion protein was separated by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min and dissolved in 20 mM glycine and 8 M Urea (pH 8.5). The recombinant protein was purified by HiTrap HP 5 ml (GE Healthcare) and dialyzed by D-tube Mega with a cut-off at 6–8 kDa (Merck Serono GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) using 20 mM glycine and 0.1% Tween-20 (pH 9.0). The concentration of the purified proteins was determined using a BCA kit (Pierce Chemical, Dallas, TX, USA). The proteins were identified by 10% SDS-PAGE.

Generation of monoclonal antibodies (Mabs) elicited by SP70

Three BALB/c mice and three Lou/C rats were immunized by injection with a suspension containing KLH-conjugated EV71 SP70 peptide (20 µg for mice and 50 µg for rats) emulsified with Freund's complete adjuvant (100 µl/animal), as described by Lim et al (16). After four weeks, the animals were sacrificed. The cells harvested from the mouse spleens were fused with myeloma SP2/0 cells (ATCC), as described by Yokoyama (17) and Yokoyama et al (18). The cells harvested from the rat spleens were fused with myeloma YB2/0 cells (ATCC) according to the same methods (16–18). The fused hybridoma cells were re-suspended and incubated in DMEM with 20% FBS for 10 days. Supernatants were screened by ELISA for SP70 peptide binding. The hybridoma clone with the strongest reactivity to the EV71 SP70 peptide was re-cloned twice by limiting dilution and its reactivity was re-confirmed using a home-made ELISA. Supernatants generated by sub-cloned hybridoma cells were typed for Ig type and affinity using a home-made indirect ELISA. Antibody neutralization was assessed by a micro-neutralization assay.

Generation of serum polyclonal antibodies (Pabs) elicited by inactivated EV71 or rEV71-VP1 protein

Three BALB/c mice received leg muscle injection of Freund's complete adjuvant containing 480 EU of inactivated EV71 or 50 µg of rEV71-VP1 protein (100 µl/mouse), and boosted with the same immunogen after 7 days. Two weeks after the final boost, serum was collected and purified using a HiTrap rProtein A FF column (GE Healthcare). The animals vaccinated with Freund's complete adjuvant were used as negative controls. Antibody neutralization activity was assessed by a micro-neutralization assay.

Three rabbits received leg muscle injection of Freund's complete adjuvant containing 960 EU of inactivated EV71 or 500 µg of rEV71-VP1 protein (500 µl/rabbit), and were boosted thrice with the same amount of immunogen at 2-week intervals. Ten days after the final boost, serum was collected and purified by HiTrap rProtein A FF column (GE Healthcare). The animals vaccinated with Freund's complete adjuvant were used as negative controls.

Micro-neutralization assay

Antibody samples were serially diluted in minimal essential medium (MEM) in a 96-well plate. An equal volume of virus at 1×102 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective dose)/ml was added. The mixture was cultured for 2 h at 37°C. Then, Vero cells (1×104/well) in a 96-well plate were inoculated with 100 µl of this mixture and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After 1 h, 100 µl of MEM supplemented with 10% bovine serum was added to each well. The plate was incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2 for 5–7 days. Cytopathic effects (CPEs) were observed every day using an IX51 inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Antibody neutralization titers were calculated using the Reed-Muench method (18).

Immunofluorescence assay

Vero cells infected with EV71 H3-TY were incubated in a 96-well plate at 35°C in 5% CO2. When CPEs were observed (at least 25%), cells were fixed with precooled acetone. Antibodies diluted to 1:100 in PBS were added to the plates blocked with 1% BSA in PBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing five times with PBS containing 0.01% Tween-20 (PBS-T), FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, goat anti-rat IgG, or goat anti-rabbit IgG (diluted 1:50 in PBS-T; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were added and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After washing five times with PBS-T, fluorescent images were visualized and captured using a DM BL2 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Antibody affinity for SP70 alanine scanning mutagenesis peptides determined by peptide-ELISA assay

All peptides were diluted in bicarbonate buffer to a final concentration of 2 µg/ml and coated on polystyrene flat bottom 96-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at 4°C overnight (100 µl/well). Peptide representing the coxsackievirus A16 VP1 epitope (aa 208–222) was added to each well as a negative control. Every peptide was respectively coated on different wells for duplication. The coated wells were washed thrice with PBS-T, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS (200 µl/well), and incubated 1 h at 37°C. After washing thrice with PBS-T, antibodies diluted in PBS-T were added to the coated wells (100 µl/well in duplicate) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed thrice with PBS-T, and antibody binding was detected by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, goat anti-rat IgG, or goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:5,000 in PBS-T (100 µl/well) for 1 h at 37°C. Plates were washed four times in PBS-T and bound antibodies were detected using 100 µl/well of freshly prepared O-phenylenediamine (0.4 mg/ml) containing H2O2 (0.4 mg/ml) in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 5.2) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 15 min, the peroxidase reaction was stopped using 2.0 M H2SO4 (50 µl/well). The OD was measured at 490 nm on a R680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Results were displayed as S/N value, i.e., the ratio of ODsample to ODnegative control 1. Negative control 1 was the negative control of the peptide-ELISA map (PEM) detection; it was used to eliminate the background of the polypeptide itself. If the average absorbance value of the negative control 1 was lower than 0.05, the value was fixed at 0.05.

Human blood sample assay

The study using clinical samples was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Zhejiang Academy of Medical Science, and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The blood samples were provided by the Ningbo Disease Prevention and Control Center (Ningbo, China). The written informed consents were obtained from the patients.

A competitive ELISA was used to measure the affinity to SP70 peptide The SP70 primary peptides were diluted to 20 µg/ml with carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), added into 96-well plate (100 µl/well), and incubation overnight at 4°C. The plate was washed four times and blocked with 1% BSA. The plate was again washed four times. Positive blood samples were diluted 500 times with PBS-T containing 1% BSA, and then divided into 18 aliquots. SP70 mutant peptides (including CA16) was added to each aliquot to reach a final concentration of 400 µg/ml, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C. A DMSO control group (DMSO as peptide solvent) was set up. The next day, the samples were added to a pre-coated 96-well plate (100 µl/well, in triplicates), and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The plate was washed four times and incubated with goat anti-human IgGHRP antibody (1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 37°C for 30 min. The plate was washed four times and added with TMB for developing. The reaction was stopped with 2 N H2SO4. The binding activity of the SP70 mutant peptide to the SP70 antibody was evaluated by the S/N ratio. S was obtained from each peptide-treated serum and N was from the DMSO treated serum. The binding activity of SP70 mutant peptide to SP70 antibody was inversely proportional to the ratio (S/N).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using ANOVA with the least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P-values were <0.05.

Results

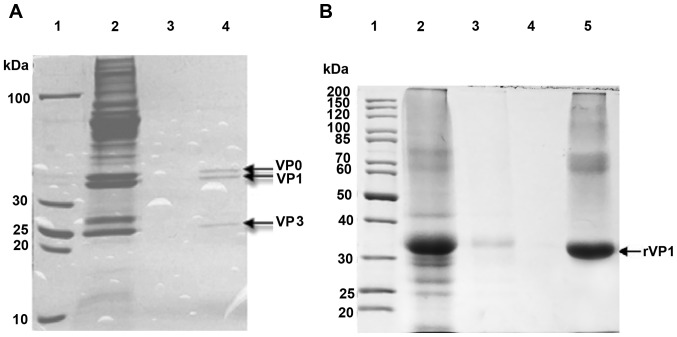

Purification of inactivated EV71 and rEV71-VP1 protein

The purification of inactivated EV17 and VP1 recombinant protein immunogens was assessed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The SDS-PAGE of purified (sepharose 6-FF column) inactivated virus revealed three bands, corresponding to VP0, VP1, and VP3 (Fig. 1A, lane 4). Recombinant VP1 was purified by HiTrap HP column, and SDS-PAGE revealed a single band (34 kDa) (Fig. 1B, lane 5), close to its theoretical molecular weight (33.9 kDa).

Figure 1.

Purification of EV71 (H3-TY) immunogens. (A) SDS-PAGE of inactivated EV71 purified by 12% acrylamide gel. Lane 1: Marker. Lane 2: Unpurified culture supernatant. Lane 3: Flow-through from sepharose 6-FF column. Lane 4: Purified EV71 inactivated virus. Each lane was loaded with 50 µl of sample with 6× loading dye. (B) SDS-PAGE of VP1 in 10% acrylamide gel. Lane 1: Marker. Lane 2: E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pET32a-rEV71 VP1 precipitate dissolved in Urea. Lanes 3 and 4: Flow-through from HiTrap HP column. Lanes 5: Purified rVP1. Each lane was loaded with 10 µl of sample with 2× loading dye. EV71, enterovirus 71; rVP1, recombinant protein of EV71 VP1.

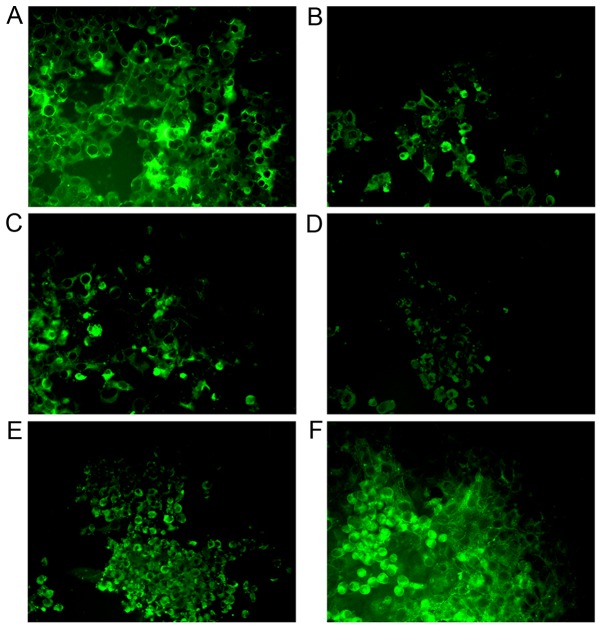

Specificity of antibodies binding to the EV71-infected Vero cells

The specificity of antibodies binding to the EV71-infected Vero cells was determined by immunofluorescence. All antibodies could specifically bind to EV71 in Vero cells, but mouse Mab elicited by SP70 and Pabs from rabbit serum elicited by inactivated EV71 showed the strongest specificity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Specificity of antibodies binding to EV71 infected Vero cells. Antibody specificity was determined by immunofluorescence (magnification, ×200). Vero cells were inoculated with EV71 and cytopathic effects were visible 2 days after infection when cells were fixed and labeled with EV71-directed antibodies and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, goat anti-rat IgG, or goat anti-rabbit IgG. EV71 was recognized by all antibodies. (A) Mouse monoclonal antibody elicited by SP70. (B) Rat monoclonal antibody elicited by SP70. (C) Polyclonal antibodies from mouse serum elicited by EV71 rVP1. (D) Polyclonal antibodies from rabbit serum elicited by EV71 rVP1. (E) Polyclonal antibodies from mouse serum elicited by inactivated EV71. (F) Polyclonal antibodies from rabbit serum elicited by inactivated EV71. EV71, enterovirus 71; rVP1, recombinant protein of EV71 VP1.

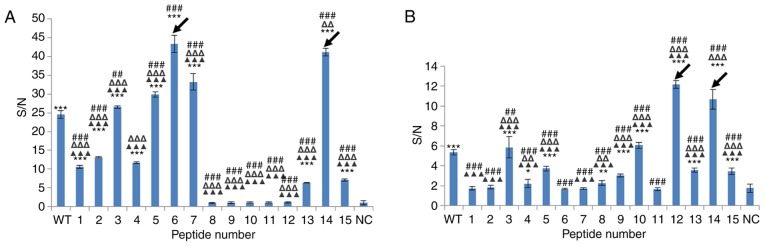

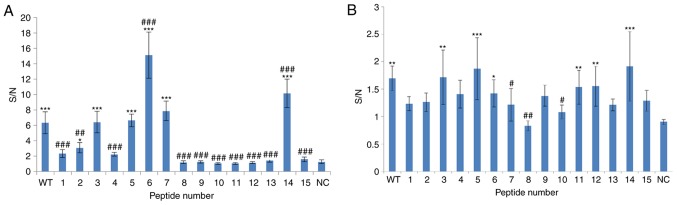

Reactivity of mouse and rat Mabs elicited by SP70 to SP70 alanine scanning mutated peptides

Mouse and rat Mabs purified from sub-cloned hybridoma cells had good neutralizing titers (1:112.36 for mouse Mab and 1:89.29 for rat Mab) (Table II). Although triggered by the same antigen, the PEMs of Mabs isolated from mice and rats were different (Fig. 3). The SP70 epitope binding affinity of mouse Mab was enhanced by alanine substitution at sites 210, 212, 213, 214 and 221 (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.01; vs. negative control peptide, all P<0.001), weakened by alanine substitution at sites 208, 209, 211, 220 and 222 (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.001; vs. negative control peptide, all P<0.001), and almost lost by alanine substitution at sites 215, 216, 217, 218 and 219 (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.001; vs. negative control peptide, all P>0.05) (Fig. 3A).

Table II.

Neutralization titers of anti-EV71 antibodies.

| Antibody | Antibody type | Source | Immunogen | Neutralization titers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-M | Monoclonal | Mouse | KLH-peptide | 112.36 |

| S-M-P1 | Polyclonal | Mouse | rVP1 | 56.11 |

| S-M-P2 | Polyclonal | Mouse | rVP1 | 52.43 |

| S-M-P3 | Polyclonal | Mouse | rVP1 | 50.27 |

| S-M-V1 | Polyclonal | Mouse | Inactivated virus | 49.48 |

| S-M-V2 | Polyclonal | Mouse | Inactivated virus | 45.19 |

| S-M-V3 | Polyclonal | Mouse | Inactivated virus | 42.67 |

| M-R | Monoclonal | Rat | KLH-peptide | 89.29 |

| S-R-P1 | Polyclonal | Rabbit | rVP1 | 28.92 |

| S-R-P2 | Polyclonal | Rabbit | rVP1 | 27.35 |

| S-R-P3 | Polyclonal | Rabbit | rVP1 | 25.24 |

| S-R-V1 | Polyclonal | Rabbit | Inactivated virus | 75.18 |

| S-R-V2 | Polyclonal | Rabbit | Inactivated virus | 70.08 |

| S-R-V3 | Polyclonal | Rabbit | Inactivated virus | 69.26 |

M-M, mouse monoclonal antibody elicited by SP70; M-R, rat monoclonal antibody elicited by SP70; S-R-V1, 2, 3: rabbit serum polyclonal antibodies elicited by EV71 inactivated virus; S-R-P1, 2, 3: rabbit serum polyclonal antibodies elicited by EV71 rVP1; S-M-V1, 2, 3: mouse serum polyclonal antibodies elicited by EV71 inactivated virus; S-M-P1, 2, 3: mouse serum polyclonal antibodies elicited by EV71 rVP1. EV71, enterovirus 71; rVP1, recombinant protein of EV71 VP1; KLH, keyhole limpet hemocyanin.

Figure 3.

Reactivity of mouse and rat monoclonal antibodies elicited by SP70 to SP70 alanine scanning mutagenesis peptides. The peptide-ELISA map was created with monoclonal antibody binding to each peptide. Results were displayed by S/N value, which is the ratio of ODsample to ODnegative control 1. Negative control 1 was the negative control of the peptide-ELISA map detection, used to eliminate the background of the polypeptide itself. A peptide representing the coxsackievirus A16 VP1 epitope (aa 208–222) was used a negative control of the EV71 VP1 SP70 epitope (aa 208–222) (NC). (A) Mouse monoclonal antibody (diluted 1:5,000). ***P<0.001 vs. NC group; ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs. wild-type (WT) SP70; ΔΔP<0.01, ΔΔΔP<0.001 vs. peptide with alanine substitution at position 6; ▲▲▲P<0.05 vs. peptide with alanine substitution at position 14. (B) Rat monoclonal antibody (diluted 1:1,000). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC group; ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs. WT SP70; ΔΔP<0.01, ΔΔΔP<0.001 vs. peptide with alanine substitution at position 12; ▲▲▲P<0.05 vs. peptide with alanine substitution at position 14. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation from three vaccinated mice or rats. Black arrows indicate mutated SP70 peptides with the strongest affinity to monoclonal antibodies. OD, optical density; aa, amino acid; NC, negative control.

The SP70 epitope binding affinity of rat Mab was increased by alanine substitution at sites 210, 217, 219 and 221 (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.01; vs. negative control peptide, all P<0.001), weakened by alanine substitution at sites 211, 212, 215, 216, 220 and 222 (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.001; vs. negative control peptide, all P<0.05), and almost lost by alanine substitution at sites 208, 209, 213, 214 and 218 (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.001; vs. negative control peptide, all P>0.05) (Fig. 3B).

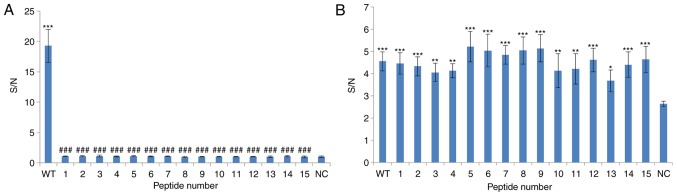

Reactivity of mouse and rabbit serum Pabs elicited by EV71 rVP1 to SP70 alanine scanning mutated peptides

Mouse and rabbit serum Pabs elicited by Freund's complete adjuvant containing rEV71-VP1 protein were collected. Neutralizing activities of all serum Pabs were assessed by micro-neutralization assay (Table II). Rabbit serum Pabs neutralized rEV71-VP1 protein at titers of 25.24 to 28.92, and mouse serum Pabs neutralized rEV71-VP1 protein at titers of 50.27 to 56.11.

PEMs of mouse serum Pabs elicited by rEV71-VP1 protein presented the same trend as mouse Mab elicited by SP70 (Fig. 4A). The ability of SP70 epitope binding to mouse serum Pabs was enhanced by mutations at sites 213 and 221 (vs. wild-type peptide, both P<0.001). Mutations at sites 210, 212 and 214 did not influence the affinity (vs. wild-type peptide, all P>0.05; vs. negative control peptide, all P<0.001). Mutation at site 209 weakened the affinity (vs. wild-type peptide, P<0.05; vs. negative control peptide, P<0.05). Mutations at the other sites led to loss of affinity (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.05; vs. negative control peptide, all P>0.05). Meanwhile, mutations at sites 214, 215 and 217 led to loss of recognition by the rabbit serum Pabs elicited by rEV71-VP1 protein (vs. wild-type peptide; all P<0.05; vs. negative control peptide, all P>0.05), while most other mutations did not influence antibody binding (vs. wild-type peptide, all P>0.05) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Reactivity of mouse and rabbit serum polyclonal antibodies elicited by EV71 rVP1 to SP70 alanine scanning mutagenesis peptides. The peptide-ELISA map was created with serum polyclonal antibodies binding to each mutated SP70 peptides. (A) Polyclonal antibodies from mouse serum elicited by EV71 rVP1. (B) Polyclonal antibodies from rabbit serum elicited by EV71 rVP1. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three vaccinated animals. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC group; ###P<0.001 vs. WT SP70. EV71, enterovirus 71; rVP1, recombinant protein of EV71 VP1; WT, wild-type; NC, negative control.

Reactivity of mouse and rabbit serum Pabs elicited by inactivated EV71 to SP70 alanine scanning mutated peptides. Mouse and rabbit serum Pabs elicited by Freund's complete adjuvant containing inactivated EV71 were collected. Neutralizing activities of all serum Pabs were assessed by micro-neutralization assay (Table II). Rabbit serum Pabs neutralized inactivated EV71 at titers of 69.26 to 75.18, and mouse serum Pabs neutralized rEV71-VP1 protein at titers of 42.67 to 49.48.

Mouse serum antibody elicited by inactivated EV71 (Fig. 5A) bound to wild-type SP70, but lost its affinity for mutated peptides (vs. wild-type peptide, all P<0.001; vs. negative control peptide, all P>0.05). Conversely, rabbit serum antibody elicited by inactivated EV71 robustly recognized SP70 mutants (vs. wild-type peptide, all P>0.05; vs. negative control peptide, all P<0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Reactivity of mouse and rabbit serum polyclonal antibodies elicited by inactivated EV71 to SP70 alanine scanning mutagenesis peptides. The peptide-ELISA map was created with serum polyclonal antibodies binding to each mutated SP70 peptides. (A) Polyclonal antibodies from mouse serum elicited by inactivated EV71. (B) Polyclonal antibodies from rabbit serum elicited by inactivated EV71. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three vaccinated animals. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs. WT SP70. EV71, enterovirus 71; rVP1, recombinant protein of EV71 VP1; WT, wild-type; NC, negative control.

Human blood sample assay

Table III shows five blood samples from EV71-infected patients had neutralizing activity against SP70. Compared with the DMSO group, wild-type peptide and peptides with mutations at the sites 209, 211, 214, 215, 216, 217, 219 and 221 had a higher reactivity with SP70 antibody in the serum (all P<0.05). Compared with the wild-type, mutations at the sites 209, 219 and 221 of SP70 lead to increased affinity with the serum antibodies (all P<0.05) (Table IV).

Table III.

Neutralizing activity of blood samples from EV71-infected patients.

| EV71 PCR | Neutralizing activity | |

|---|---|---|

| YY-164 | Positive | >1,024 |

| YY-142 | Positive | 1,024 |

| YY-148 | Positive | 768 |

| YY-15 | Positive | 1,024 |

| YY-123 | Positive | >1,024 |

EV71, enterovirus 71; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Table IV.

Reactivity of blood samples from EV71-infected patients to mutated SP70 peptides.

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Peptide | Mean (I-J) | Standard error | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value |

| DMSO | Wild-type | 29.2 | 6.7 | 15.8 | 42.5 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 1.8 | 6.7 | −11.5 | 15.2 | 0.783 | |

| 2 | 55.4 | 6.7 | 42.1 | 68.8 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | 18.5 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 31.8 | 0.007 | |

| 4 | 43.9 | 6.7 | 30.6 | 57.2 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | 9.2 | 6.7 | −4.1 | 22.6 | 0.171 | |

| 6 | 9.6 | 6.7 | −3.8 | 22.9 | 0.156 | |

| 7 | 21.1 | 6.7 | 7.8 | 34.4 | 0.002 | |

| 8 | 45.2 | 6.7 | 31.8 | 58.5 | <0.001 | |

| 9 | 22.4 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 35.7 | 0.001 | |

| 10 | 32.6 | 6.7 | 19.3 | 45.9 | <0.001 | |

| 11 | 11.6 | 6.7 | −1.8 | 24.9 | 0.088 | |

| 12 | 54.6 | 6.7 | 41.3 | 67.9 | <0.001 | |

| 13 | 4.7 | 6.7 | −8.6 | 18.0 | 0.484 | |

| 14 | 56.2 | 6.7 | 42.9 | 69.5 | <0.001 | |

| 15 | 8.4 | 6.7 | −4.9 | 21.7 | 0.212 | |

| NC | 18.7 | 6.7 | 5.4 | 32.0 | 0.007 | |

| Wild-type | 1 | −27.3 | 6.7 | −40.6 | −14.0 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 26.3 | 6.7 | 13.0 | 39.6 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | −10.7 | 6.7 | −24.0 | 2.6 | 0.114 | |

| 4 | 14.7 | 6.7 | 1.4 | 28.0 | 0.031 | |

| 5 | −19.9 | 6.7 | −33.2 | −6.6 | 0.004 | |

| 6 | −19.6 | 6.7 | −32.9 | −6.3 | 0.005 | |

| 7 | −8.1 | 6.7 | −21.4 | 5.3 | 0.232 | |

| 8 | 16.0 | 6.7 | 2.7 | 29.3 | 0.019 | |

| 9 | −6.7 | 6.7 | −20.1 | 6.6 | 0.316 | |

| 10 | 3.4 | 6.7 | −9.9 | 16.8 | 0.610 | |

| 11 | −17.6 | 6.7 | −30.9 | −4.3 | 0.010 | |

| 12 | 25.4 | 6.7 | 12.1 | 38.8 | <0.001 | |

| 13 | −24.5 | 6.7 | −37.8 | −11.1 | <0.001 | |

| 14 | 27.0 | 6.7 | 13.7 | 40.4 | <0.001 | |

| 15 | −20.7 | 6.7 | −34.1 | −7.4 | 0.003 | |

| NC | −10.5 | 6.7 | −23.8 | 2.9 | 0.122 | |

| DMSO | −29.2 | 6.7 | −42.5 | −15.8 | <0.001 | |

EV71, enterovirus 71; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; CI, confidence interval; NC, negative control.

Discussion

The EV71 epitope SP70 is the target of EV71 neutralizing antibodies (17). Mice can produce neutralizing antibodies against EV71 after vaccination with a synthetic SP70 peptide and suckling Balb/c mice can fight EV71 infections by passive transfer of anti-SP70 antibodies (18). In the present study, mice, rats, and rabbits were inoculated with inactivated EV71, rEV71-VP1 protein, or KLH-conjugated EV71 SP70 peptide. All immunization protocols generated EV71 neutralizing antibodies, with titers ranging from 1:25.24 (serum Pabs of rabbit elicited by rEV71-VP1 protein) to 112.36 (Mab of mouse elicited by SP70). Immunofluorescence showed that all antibodies could specifically bind to EV71 in Vero cells, but mouse Mab elicited by SP70 and Pabs from rabbit serum elicited by inactivated EV71 showed the strongest specificity.

Previous studies showed that changing a single AA can change the affinity of the peptide to antibodies. Indeed, Wunderlich et al (19) showed the affinity of antibodies to the PA protein of influenza A virus polymerase can be modulated by substituting single aa. Similar observations were made when substituting single aa in the hemagglutinin protein of the influenza virus (20) and in the capsid protein of porcine circovirus 2 (21). In the present study, an alanine scanning mutagenesis protocol was used to synthesize fifteen SP70 mutated peptides. The affinity of EV71-specific antibodies to these mutated peptides was assessed by ELISA. The capacity of these antibodies to recognize SP70 mutants differed among species. Mouse serum antibody elicited by inactivated EV71 bound to wild-type SP70, but lost its affinity for mutated peptides. Conversely, rabbit serum antibody elicited by inactivated EV71 robustly recognized SP70 mutants. These observations indicate that rabbit serum Pabs elicited by inactivated EV71 were more flexible, recognizing a wider range of SP70 variants. Meanwhile, mutations at sites 214, 215 and 217 led to loss of recognition by the rabbit serum Pabs elicited by the rEV71-VP1 protein, indicating that in rabbits the robustness of the SP70-directed antibody response was weakened by vaccination with only the rEV71-VP1 protein, rather than the whole virus. Two Mabs from mice and rats, elicited by the same SP70 antigen, exhibited reduced affinity for different mutant peptides, indicating that the key antigenic SP70 residues differed between these animals. Liu et al also observed differences in VP1-directed responses among species following immunization with inactivated EV71 (22). These observations indicate that the B cell repertoire to key antigenic residues in SP70 differs among species, as inoculation of rabbits, rats, and mice elicited antibodies directed to different segments of the SP70 epitope.

Mouse serum antibody elicited by inactivated EV71 bound to wild-type SP70, but lost its affinity for mutated peptides. The mouse serum Pabs elicited by EV71 rVP1 protein presented the same trend as mouse Mab elicited by SP70. The rVP1 protein may present the SP70 epitope as a linear antigen. Our observations thus suggest that the structure is also important for SP70 epitope to elicit robust antibody responses, but this point needs further study.

Surprisingly, we observed that some antibodies exhibited enhanced affinity for specific SP70 mutants. The SP70 epitope binding affinity of the mouse Mab was enhanced by alanine substitution at sites 210, 212, 213, 214 and 221, while the SP70 epitope binding affinity of the rat Mab was enhanced by alanine substitution at sites 210, 217, 219 and 221. Furthermore, the SP70 epitope binding affinity of Pabs from mouse serum elicited by rEV71-VP1 was enhanced by alanine substitution at sites 213 and 221. On the other hand, mouse serum antibody elicited by inactivated EV71 bound to wild-type SP70, but lost affinity for mutated peptides. These enhancements appear to be influenced by species and structure of SP70. These observations also suggest that an optimized SP70 peptide may possess higher immunogenicity in some species. This peptide antigen has even been used in the production of recombinant vaccines that have elicited neutralizing responses in mice (12,23). These observations highlight the potential role of this peptide as immunogen in EV71 vaccination that may elicit a protective antibody response to a wide variety of EV71 subtypes (22). Future work should investigate the immunogenicity and the capacity of inducing neutralizing antibody response for these mutant SP70 peptides in mice or rabbits.

Antibody responses triggered by inactivated EV71, rEV71-VP1, and KLH-conjugated EV71 SP70 peptide differed among species in neutralizing capacity and affinity for SP70 mutant peptides. Mutations in SP70 both reduced and enhanced antibody affinity and these changes varied among the immunogen and species used to generate the antibodies. These observations highlight the potential for optimization of a novel SP70 subunit antigen for EV71 vaccine design.

Acknowledgements

Te present study was supported by Zhejiang Pukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) and they provided the EV71/H3-TY virus strain. This study was supported by the Zhejiang Province Science Department (2010C03005), the ‘Qianjiang’ Talent Project from Zhejiang Province (2012R100081), and the Zhejiang Province Key Laboratory of Biological Vaccine R&D (2008F3022).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- aa

amino acid

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EV71

enterovirus 71

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HFMD

hand, foot, and mouth disease

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- LSD

least significant difference

- MEM

minimal essential medium

- OD

optical density

- PEMs

peptide-ELISA maps

References

- 1.Sanders SA, Herrero LJ, McPhie K, Chow SS, Craig ME, Dwyer DE, Rawlinson W, McMinn PC. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71 over two decades in an Australian urban community. Arch Virol. 2006;151:1003–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato C, Syoji M, Ueki Y, Sato Y, Okimura Y, Saito N, Kikuchi N, Yagi T, Numakura H. Isolation of enterovirus 71 from patients with hand, foot and mouth disease in a local epidemic on March 2006, in Miyagi prefecture, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59:348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang LY. Enterovirus 71 in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2008;49:103–112. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tee KK, Takebe Y, Kamarulzaman A. Emerging and re-emerging viruses in Malaysia, 1997–2007. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lum LC, Wong KT, Lam SK, Chua KB, Goh AY. Neurogenic pulmonary oedema and enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis. Lancet. 1998;352:1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60789-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao LX, Wu B, Bao WX, Han FA, Xu L, Ge QJ, Yang J, Yuan ZH, Miao CH, Huang XX, et al. Epidemiology of hand, foot, and mouth disease and genotype characterization of enterovirus 71 in Jiangsu, China. J Clin Virol. 2010;49:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Tan XJ, Wang HY, Yan DM, Zhu SL, Wang DY, Ji F, Wang XJ, Gao YJ, Chen L, et al. An outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease associated with subgenotype C4 of human enterovirus 71 in Shandong, China. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan KP, Goh KT, Chong CY, Teo ES, Lau G, Ling AE. Epidemic hand, foot and mouth disease caused by human enterovirus 71, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:78–85. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.020112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang LY, Lin TY, Huang YC, Tsao KC, Shih SR, Kuo ML, Ning HC, Chung PW, Kang CM. Comparison of enterovirus 71 and coxsackie-virus A16 clinical illnesses during the Taiwan enterovirus epidemic, 1998. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:1092–1096. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199912000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang SM, Liu CC, Tseng HW, Wang JR, Huang CC, Chen YJ, Yang YJ, Lin SJ, Yeh TF. Clinical spectrum of enterovirus 71 infection in children in southern Taiwan, with an emphasis on neurological complications. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:184–190. doi: 10.1086/520149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Qian Y, Wang S, Serrano JM, Li W, Huang Z, Lu S. EV71: An emerging infectious disease vaccine target in the Far East? Vaccine. 2010;28:3516–3521. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foo DG, Alonso S, Chow VT, Poh CL. Passive protection against lethal enterovirus 71 infection in newborn mice by neutralizing antibodies elicited by a synthetic peptide. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foo DG, Alonso S, Phoon MC, Ramachandran NP, Chow VT, Poh CL. Identification of neutralizing linear epitopes from the VP1 capsid protein of enterovirus 71 using synthetic peptides. Virus Res. 2007;125:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MS, Chang LY. Development of enterovirus 71 vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9:149–156. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown BA, Pallansch MA. Complete nucleotide sequence of enterovirus 71 is distinct from poliovirus. Virus Res. 1995;39:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim XF, Jia Q, Chow VT, Kwang J. Characterization of a novel monoclonal antibody reactive against the N-terminal region of enterovirus 71 VP1 capsid protein. J Virol Methods. 2013;188:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yokoyama WM. Production of monoclonal antibodies. Curr Protoc Cell Biol Chapter. 2001;16 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1601s03. Unit 16 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama WM, Christensen M, Dos Santos G, Miller D, Ho J, Wu T, Dziegelewski M, Neethling FA. Production of monoclonal antibodies. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2013;102 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0205s102. Unit 2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wunderlich K, Juozapaitis M, Ranadheera C, Kessler U, Martin A, Eisel J, Beutling U, Frank R, Schwemmle M. Identification of high-affinity PB1-derived peptides with enhanced affinity to the PA protein of influenza A virus polymerase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:696–702. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01419-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ping J, Li C, Deng G, Jiang Y, Tian G, Zhang S, Bu Z, Chen H. Single-amino-acid mutation in the HA alters the recognition of H9N2 influenza virus by a monoclonal antibody. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:168–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saha D, Lefebvre DJ, Ooms K, Huang L, Delputte PL, Van Doorsselaere J, Nauwynck HJ. Single amino acid mutations in the capsid switch the neutralization phenotype of porcine circovirus 2. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:1548–1555. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.042085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu CC, Chou AH, Lien SP, Lin HY, Liu SJ, Chang JY, Guo MS, Chow YH, Yang WS, Chang KH, et al. Identification and characterization of a cross-neutralization epitope of enterovirus 71. Vaccine. 2011;29:4362–4372. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plevka P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science. 2012;336:1274. doi: 10.1126/science.1218713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]