Abstract

Introduction

Patients presenting with right iliac fossa (RIF) pain are a common challenge for acute general surgical services. Given the range of potential pathologies, RIF pain creates diagnostic uncertainty and there is subsequent variation in investigation and management. Appendicitis is a diagnosis which must be considered in all patients with RIF pain; however, over a fifth of patients undergoing appendicectomy, in the UK, have been proven to have a histologically normal appendix (negative appendicectomy). The primary aim of this study is to determine the contemporary negative appendicectomy rate. The study’s secondary aims are to determine the rate of laparoscopy for appendicitis and to validate the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) and Alvarado prediction scores.

Methods and analysis

This multicentre, international prospective observational study will include all patients referred to surgical specialists with either RIF pain or suspected appendicitis. Consecutive patients presenting within 2-week long data collection periods will be included. Centres will be invited to participate in up to four data collection periods between February and August 2017. Data will be captured using a secure online data management system. A centre survey will profile local policy and service delivery for management of RIF pain.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics are not required for this study in the UK, as determined using the National Research Ethics Service decision tool. This study will be registered as a clinical audit in participating UK centres. National leads in countries outside the UK will oversee appropriate registration and study approval, which may include completing full ethical review. The study will be disseminated by trainee-led research collaboratives and through social media. Peer-reviewed publications will be published under corporate authorship including ‘RIFT Study Group’ and ‘West Midlands Research Collaborative’.

Keywords: abdominal pain, surgery, appendicitis, appendicectomy, right iliac fossa pain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will collect prospective, observational data on a large number of patients across Europe. A preplanned validation process will verify case ascertainment and data accuracy.

The study uses the UK National Research Collaborative model to capture high-quality data while minimising the burden on participating centres.

Unlike previous studies, the clinical risk scores will be validated against a prospective cohort of patients presenting with undifferentiated right iliac fossa pain rather than patients who have undergone appendicectomy.

Within the remit of this observational study, it will not be possible to track patient readmissions to centres other than the index admitting hospital or readmission rates beyond 30 days.

This protocol is designed to be carried out alongside routine clinical practice. This limits the quantity and complexity of data it is feasible to collect. Specific data regarding antibiotic therapy for RIF pain and presenting symptoms outside of those included within risk scores will not be collected.

Introduction

Right iliac fossa (RIF) pain is one of the most common presentations to acute general surgical services.1 Causes include appendicitis, other gastrointestinal, urological, gynaecological, vascular and musculoskeletal pathologies. Given this range of potential pathologies, variation in presentation and similarity to other conditions, particularly ovarian pathologies in women of reproductive age, diagnosing appendicitis can be a challenge.2 Traditionally, surgeons have relied on clinical history, examination findings and basic laboratory investigations for diagnosis. Objective stratifiers such as the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR)3 and Alvarado scores4 have been developed to combat this diagnostic uncertainty; yet, these derived from small retrospective cohorts, are poorly validated, and not widely used.5

Since delayed appendicectomy is associated with increased risk of complications, prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential.6 Diagnostic uncertainty, coupled with the risks of diagnostic delay, has led to surgeons having a low threshold for operating on patients with equivocal symptoms resulting in high rates of negative appendicectomy: a national audit in 2012 found the UK’s negative appendicectomy rate to be 20.6%.7 8

Recent guidelines stipulate that appendicectomy should be performed laparoscopically unless this is contraindicated9 10 (table 1). However, in 2012 one-third of patients underwent open appendicectomy.7 Unlike laparoscopic surgery, open procedures typically commit the surgeon to proceed to appendicectomy even if the appendix is found to be macroscopically normal once visualised.8

Table 1.

A complete compilation and comparison of the WSES 2016 and the EAES 2016 guidance on the investigation and management of appendicitis

| Society | Statement number | Guidance statement | Captured within the RIFT Study |

| (1) Diagnostic efficiency of clinical scoring systems | |||

| EAES | Preop R1 | The combined variables of clinical assessment and biochemical testing in the Alvarado score should be used to determine the likelihood of appendicitis. | Yes |

| WSES | 1.1 | The Alvarado score (with cut-off score<5) is sufficiently sensitive to exclude acute appendicitis. | Yes |

| WSES | 1.2 | The Alvarado score is not sufficiently specific in diagnosing acute appendicitis. | Yes |

| WSES | 1.3 | An ideal (high sensitivity and specificity), clinically applicable, diagnostic scoring system/clinical rule remains outstanding. This remains an area for future research. | Yes |

| (2) Role of imaging | |||

| WSES | 2.1 | In patients with suspected appendicitis, a tailored individualised approach is recommended, depending on disease probability, sex and age of the patient. | Yes |

| WSES | 2.2 | Imaging should be linked to Risk Stratification such as AIR or Alvarado score | Yes |

| WSES | 2.3 | Low-risk patients being admitted to hospital and not clinically improving or reassessed score could have appendicitis ruled-in or out by abdominal CT. | Yes |

| WSES | 2.4 | Intermediate risk classification identifies patients likely to benefit from observation and systematic diagnostic imaging. | Yes |

| WSES | 2.5 | High-risk patients (younger than 60 years old) may not require preoperative imaging. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R2 | We recommend that ultrasound should be performed as a first-level diagnostic imaging although it has lower diagnostic value in case radiological confirmation is desirable. | Yes |

| WSES | 2.6 | US standard reporting templates for ultrasound and US three-step sequential positioning may enhance over accuracy. | |

| EAES | Preop R3 | If after ultrasound the diagnosis of appendicitis is not confirmed nor ruled out, we suggest that additional imaging studies (either a CT or MRI) should be performed. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R4 | In obese patients, a CT or MRI is more accurate than ultrasonography. In case of diagnostic doubt, we recommend a CT or MRI in these specific patients. | |

| EAES | Preop R5 | In pregnant patients, radiation should be avoided. In case of diagnostic doubt, we recommend an MRI in these specific patients. | |

| WSES | 2.7 | MRI is recommended in pregnant patients with suspected appendicitis, if this resource is available | |

| EAES | Preop R6 | In children radiation should be avoided. In case of diagnostic doubt, we recommend an MRI in these specific patients. | Yes |

| (3) Non-operative treatment for uncomplicated appendicitis | |||

| WSES | 3.1 | Antibiotic therapy can be successful in selected patients with uncomplicated appendicitis who wish to avoid surgery and accept the risk up to 38% recurrence. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R7 | Non-operative treatment (with antibiotics) of uncomplicated appendicitis in adults is not suggested as high-quality evidence of superiority is still lacking. | Yes |

| WSES | 3.2 | Current evidence supports initial intravenous antibiotics with subsequent conversion to oral antibiotics. | |

| WSES | 3.3 | In patients with normal investigations and symptoms unlikely to be appendicitis but which do not settle: 1) cross-sectional imaging is recommended before surgery; 2) laparoscopy is the surgical approach of choice and 3) there is inadequate evidence to recommend a routine approach at present | Yes |

| (4) Timing of appendectomy and in-hospital delay | |||

| WSES | 4.1 | Short, in-hospital surgical delay up to 12/24 hours is safe in uncomplicated acute appendicitis and does not increase complications and/or perforation rate. | Yes |

| WSES | 4.2 | Surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis can be planned for next available list minimising delay wherever possible (patient comfort, etc). | Yes |

| EAES | Operative R1 | We recommend that surgery is performed as soon as feasible after diagnosis. | Yes |

| (5) Surgical treatment | |||

| WSES | 5.1.1 | Laparoscopic appendectomy should represent the first choice where laparoscopic equipment and skills are available, since it offers clear advantages in terms of less pain, lower incidence of SSI, decreased LOS, earlier return to work and overall costs. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R8 | Laparoscopic appendectomy is recommended as the procedure of choice in adults with uncomplicated acute appendicitis. | Yes |

| WSES | 5.1.2 | Laparoscopy offers clear advantages and should be preferred in obese patients, older patients and patients with comorbidities. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R11 | Laparoscopic appendectomy is recommended as the procedure of choice in obese patients with acute appendicitis. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R14 | Laparoscopic appendectomy is recommended as the procedure of choice in patients over 65 years of age. | Yes |

| WSES | 5.1.3 | Laparoscopy is feasible and safe in young male patients although no clear advantages can be demonstrated in such patients. | Yes |

| WSES | 5.1.4 | Laparoscopy should not be considered as a first choice over open appendectomy in pregnant patients. | |

| EAES | Preop R12 | Laparoscopic appendectomy is suggested as the procedure of choice in pregnant patients with acute appendicitis. It should even be considered in the third trimester. | |

| WSES | 5.1.5 | No major benefits have also been observed in laparoscopic appendectomy in children, but it reduces hospital stay and overall morbidity. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R13 | Laparoscopic appendectomy is suggested as the procedure of choice in children with acute appendicitis and an indication for appendectomy. | Yes |

| WSES | 5.1.6 | In experienced hands, laparoscopy is more beneficial and cost-effective than open surgery for complicated appendicitis. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R9 | Laparoscopic appendectomy is suggested as the procedure of choice in patients with perforated appendicitis. | Yes |

| EAES | After care R2 | We suggest the use of local anaesthetic for subcutaneous and muscular infiltration of incision sites prior to incision. | |

| EAES | Operative R6 | Open: supine, one or both arms out, surgeon at the right side, assistant on the left side. Laparoscopic: supine, right arm out, left arm along the body, surgeon and assistant on the left side. | |

| EAES | Operative R7 | The consensus held a preference for open access to the peritoneal cavity because of rare but serious complications associated with the Verees needle. | |

| EAES | Operative R8 | Based on the literature, no recommendation can be made which trocars should be used and their placement. This should be left at the surgeon’s discretion. Three-port technique should be standard. Single-port approaches can be used by surgeons with sufficient experience. | |

| WSES | 5.2 | Peritoneal irrigation does not have any advantages over suction alone in complicated appendicitis. | |

| WSES | 5.3.1 | There are no clinical differences in outcomes, LOS and complications rates between the different techniques described for mesentery dissection (monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar energy, metal clips, endoloops, Ligasure, Harmonic Scalpel, etc). | |

| WSES | 5.3.2 | Monopolar electrocoagulation and bipolar energy are the most cost-effective techniques, even if more experience and technical skills is required to avoid potential complications (eg, bleeding) and thermal injuries. | |

| WSES | 5.4.1 | There are no clinical advantages in the use of endostapler over endoloops for stump closure for both adults and children. | |

| EAES | Operative R10 | The use of stapler or suturing is recommended over clips or endoloops when the appendix base is inflamed, necrotic or perforated. The use of alternative measures to secure the appendiceal stump in this case may be insufficient. | |

| EAES | After care R4 | To prevent stump appendicitis, it is suggested that the appendiceal stump should be no longer than 0.5 cm. Timely diagnosis allows laparoscopic stump resection. Delayed diagnosis may require extended bowel resection. | |

| WSES | 5.4.2 | Endoloops might be preferred for lowering the costs when appropriate skills/learning curve are available. | |

| WSES | 5.4.3 | There are no advantages of stump inversion over simple ligation, either in open or laparoscopic surgery. | |

| WSES | 5.5.1 | Drains are not recommended in complicated appendicitis in paediatric patients. | |

| EAES | Operative R4 | It is suggested that there is no indication for routine postoperative nasogastric tube placement in children or adults. | |

| EAES | Operative R11 | It is recommended that extraction of the appendix should avoid direct contact of the appendix and the abdominal wall. There are several methods of achieving this and there is no evidence supporting one above the other. | |

| EAES | Operative R5 | It is suggested that there is no indication for routine postoperative catheter placement in children or adults. | |

| WSES | 5.5.2 | In adult patients, drain after appendectomy for perforated appendicitis and abscess/peritonitis should be used with judicious caution, given the absence of good evidence from the literature. Drains did not prove any efficacy in preventing intra-abdominal abscess and seem to be associated with delayed hospital discharge. | |

| EAES | Operative R12 | In general, meticulous suction of intraperitoneal fluid or collections is suggested; the philosophy should be: ‘leave no pus behind’. Routine use of drains in appendectomy is not recommended. | |

| WSES | 5.6 | Delayed primary skin closure does not seem beneficial for reducing the risk of SSI and increase LOS in open appendectomies with contaminated/dirty wounds. | |

| EAES | Operative R13 | Primary wound closure is recommended for all cases of open appendectomy. | |

| EAES | Operative S1 | Various reasons exist to convert laparoscopic appendicectomy. However, no recommendation about when to convert can be given. It should be stated that conversion to open surgery is not regarded as a complication. | Yes |

| EAES | After care R3 | There is no reason to restrict the postoperative diet after an uncomplicated appendectomy. | |

| (6) Scoring systems for intraoperative grading of appendicitis and their clinical usefulness | |||

| WSES | 6.1 | The incidence of unexpected findings in appendectomy specimens is low but the intraoperative diagnosis alone is insufficient for identifying unexpected disease. From the current available evidence, routine histopathology is necessary. | Yes |

| EAES | After care R1 | It is recommended to send all appendices to the pathology department routinely and the operated will review the results. | Yes |

| EAES | Operative R15 | It is suggested that definitive treatment of a suspected malignancy will depend on final histological and staging information after initial treatment of the operative findings and may require further surgery or adjunct treatment. | |

| WSES | 6.2 | There is a lack of validated system for histological classification of acute appendicitis and controversies exist on this topic. | |

| WSES | 6.3 | Surgeon’s macroscopic judgement of early grades of acute appendicitis is inaccurate. | Yes |

| WSES | 6.4 | If the appendix looks ‘normal’ during surgery and no other disease is found in symptomatic patient, we recommend removal in any case. | Yes |

| EAES | Operative R9 | It is suggested to remove the ‘normal’ appearing appendix when operating for suspected appendicitis when no other pathology is identified. | Yes |

| WSES | 6.5 | We recommend adoption of a grading system for acute appendicitis based on clinical, imaging and operative findings, which can allow identification of homogeneous groups of patients, determining optimal grade disease management and comparing therapeutic modalities | |

| (7) Non-surgical treatment for complicated appendicitis: abscess or phlegmon | |||

| WSES | 7.1 | Percutaneous drainage of a periappendiceal abscess, if accessible, is an appropriate treatment in addition to antibiotics for complicated appendicitis. | Yes |

| WSES | 7.2 | Non-operative management is a reasonable first-line treatment for appendicitis with phlegmon or abscess. | Yes |

| EAES | After care R5 | Initial treatment of intra-abdominal abscess is conservative with antibiotics. In some patients, this may need to be combined with radiological or surgical drainage. | Yes |

| EAES | Preop R10 | Non-operative treatment is suggested as the procedure of choice for patients with an appendiceal mass in the absence of diffuse peritonitis. Data are lacking on the benefits of interval appendectomy. | Yes |

| WSES | 7.3 | Operative management of acute appendicitis with phlegmon or abscess is a safe alternative to non-operative management in experienced hands. | Yes |

| EAES | Operative R14 | It is recommended to treat an inflammatory mass conservatively. We recommend that when encountered during laparoscopy, refrain from appendectomy. During follow-up: additional imaging is advised. Data are lacking on the benefits of interval appendectomy. | |

| WSES | 7.4 | Interval appendectomy is not routinely recommended both in adults and children. | Yes |

| WSES | 7.5 | Interval appendectomy is recommended for those patients with recurrent symptoms. | Yes |

| WSES | 7.6 | Colonic screening should be performed in those patients with appendicitis treated non-operatively if >40 years old. | |

| (8) Preoperative and postoperative antibiotics | |||

| WSES | 8.1 | In patients with acute appendicitis, preoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics are always recommended. | |

| EAES | Operative R2 | Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended in appendectomy in adults. | |

| EAES | Operative R3 | Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended in appendectomy in children. | |

| WSES | 8.2 | For patients with uncomplicated appendicitis, postoperative antibiotics are not recommended. | |

| EAES | After care S1 | Evidence for duration of administration of postoperative antibiotics is lacking. | |

| EAES | After care S2 | There is no evidence of routine use of postoperative antibiotics in uncomplicated appendicitis. | |

| EAES | After care R6 | In complicated appendicitis, postoperative antibiotics are recommended. | |

| WSES | 8.3 | In patients with complicated acute appendicitis, postoperative, broad-spectrum antibiotics are always recommended. | |

| WSES | 8.4 | Although discontinuation of antimicrobial treatment should be based on clinical and laboratory criteria such as fever and leucocytosis, a period of 3–5 days for adult patients is generally recommended. | |

Those statements captured within the RIFT study’s data collection have been highlighted. The EAES guidance is split into statements (S) and recommendations (R) under three sections; preoperative care, operative managements and after care. The WSES guidance is numbered and listed under the sections described in the table.

EAES, European Association of Endoscopic Surgery’s guidance; LOS, length of stay; Preop, preoperative; RIFT, Right Iliac Fossa Pain Treatment; SSI, surgical site infections; WSES, World Society of Emergency Surgery.

This study will test the hypothesis that, associated with increased take-up of laparoscopy, the negative appendicectomy rate will have decreased since 2012.8 To inform the implementation of recent guidelines which mandate risk stratification of patients with RIF pain, this study will also validate the AIR and Alvarado scores in a large, prospective, international cohort.9 10

Methods and analysis

This prospective, observational, multicentre study will be coordinated by trainee-led research networks which have been described previously.11 12

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of this study is to determine the negative appendicectomy rate. The secondary aims of this study are to determine the rate of laparoscopy for appendicectomy and to validate the AIRS and Alvarado scores for acute appendicitis. A centre survey will profile local policy and service delivery for management of patients presenting with RIF pain.

Patients and centres

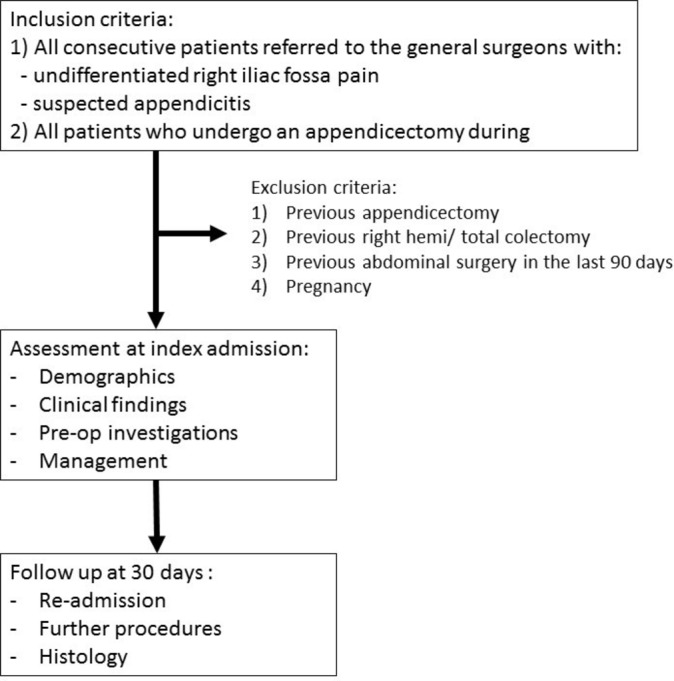

Any hospital that offers acute general surgical services will be eligible to participate. Local collaborators at each centre will prospectively collect data during 2-week long study periods, on consecutive patients referred to the general or paediatric surgery units with RIF pain or suspected appendicitis. Each centre will be able to submit data from up to four study periods between February and August 2017. Patients will be identified prospectively via hospital computer systems, handover lists and by the clinical surgical team. Patients who are pregnant have had abdominal surgery in the preceding 90 days, or have had previous appendicectomy, right hemicolectomy or total colectomy will be excluded (figure 1). Variables required to calculate the AIRS and Alvarado scores will be collected at time of presentation to the surgical unit.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Follow-up

Patients will be followed throughout their admission to determine their treatment pathway and length of stay. Data will also be collected on histology and readmission rates, for both the operated and non-operated groups, within 30 days. Collaborators will access electronic records, emergency department and theatre systems and patient notes to collect data. The group who undergo an operation will be followed up to determine the negative appendicectomy rate, and the non-operative group will be followed up to allow for the validation of the AIR and Alvarado scores low risk prediction for this group. The non-operative group will also include those patients diagnosed as simple appendicitis and treated non-operatively and will require follow-up to assess whether they then require a subsequent operation. No patient identifiable information will be collected.

Centre survey

A consultant surgeon at each participating centre will complete a short questionnaire regarding the guidelines, protocols and resources available for the investigation and management of RIF pain in their hospital (table 2).

Table 2.

Centre survey

| Data criteria | Options | |

| Centre details | ||

| 1(a) | Does your unit care for? |

|

| 2 | Does your hospital have an on-site gynaecology service? |

|

| 3 | Does your centre have ‘review clinic’ slots for patients to return for further assessment/imaging the following day if a diagnosis is unclear? |

|

| 4(a) | How many consultants will be ‘on call’ during the 2-week study period? | Number = |

| 4(b) | How many consultant general surgeons work at your centre? | Number = |

| 4(c) | Is there a dedicated registrar based on the surgical assessment unit to review patients? |

|

| 5 | At weekends, is ultrasound available? |

|

| 6(a) | At weekends, is CT available? |

|

| 6(b) | At night, is CT available? |

|

| Does your centre have an agreed policy for: | ||

| 7 | When to use appendicitis risk stratification scores? |

|

| 8 | Which patients should have a CT scan prior to appendicectomy? (eg, diagnosis unclear, age>50) |

|

| 9 | Whether some patients with appendicitis may be managed non-operatively? |

|

| 10 | Whether laparoscopic or open appendicectomy should be routinely performed? |

|

| 11 | Whether a macroscopically normal looking appendix should be removed or left in situ? |

|

Project management and recruitment

The RIFT steering committee (see online supplementary appendix 1) will be responsible for protocol development, data collection and data analysis. A structured system of national, regional and local leadership has been created to coordinate the RIFT study. National leads will oversee participation in RIFT within their countries through networks including the West Midlands Research Collaborative, UK National Surgical Research Collaborative and Italian Surgical Research Group, as well as through social media platforms.13 Regional leads will recruit, advise and ensure the correct approvals are in place for each hospital within their region. Local leads will oversee data collection in their hospital, ensuring adherence to local governance protocols and continuous data collection across the 2-week periods. Up to three collaborators per 2-week period, per hospital, will be recruited to participate. A secure server running the ‘Research Electronic Data Capture’ (REDCap, Boston, Massachusetts) web application hosted by the University of Birmingham, UK, will be used to collect and securely store data.

bmjopen-2017-017574supp001.pdf (64.7KB, pdf)

Sample size and statistical analysis

Based on pilot studies across four centres, we estimate that each centre will capture approximately 10 patients with RIF pain per week. The steering committee has received expressions of interest in participation from over 150 centres. It is estimated that around 75 centres will participate during each period. This would result in approximately 6000 patients being included in RIFT across the four data collection periods. It is anticipated that around 20% (1200 patients) will undergo appendicectomy.

Data will be reported in accordance with Strengthening The Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology guidelines for observational studies.14 Differences between patient, disease and operative specific factors will be tested using Student’s t-test for continuous data (p value) and χ2 for categorical data (reported as χ2, p value). A p-value of 0.05 will be accepted as significant.

Preplanned analyses will include and are not limited to: (1) variation in the negative appendicectomy and laparoscopy rates across participating centres and countries and (2) predictive value of AIR and Alvarado risk scores. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value will be calculated for clinical risk scores. A panelled multilevel, multivariate, binary logistic regression model, including centre as a random effect, will be used to assess the association of clinical risk scores with negative appendicectomy. The model fit will be tested with area under the curve analysis, using Somer’s test to derive a C-statistic.

Ethics

In the UK the online National Research Ethics Service decision tool (http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk) confirmed that RIFT does not require research ethics approval in the UK. The RIFT study will be registered as a clinical audit in each participating UK centre. National leads in other countries will oversee appropriate registration and study approval, which may include completing full ethical review. Local investigators will be responsible for ensuring local approvals are in place and will be required to demonstrate this to gain access to the online data collection tool.

Reporting and dissemination

A consultant surgeon will facilitate presentation of local study results at a governance meeting at each participating centre. Peer-reviewed publications will be published under corporate authorship including ‘RIFT Study Group’ and ‘West Midlands Research Collaborative’.

Discussion

The RIFT study will be a large, multicentre, international, prospective observational study of undifferentiated patients presenting with RIF pain and suspected appendicitis. By using a protocol driven, preplanned data collection tool and analysis plan, this study will ensure high data quality while minimising the burden on participating centres.

The 2012 national appendicectomy audit found a significant variation in management of appendicitis across the UK.7 In light of recent guidelines stipulating that appendicectomy in adults should be performed laparoscopically unless contraindicated,9 10 the RIFT study offers the opportunity to examine health system-level quality improvement in the delivery of laparoscopic appendicectomy 5 years on from the 2012 study. By mapping real-life patient pathways for investigation and management of RIF pain, RIFT will indicate whether any increased use of modern technologies, including CT scanning and laparoscopy, have been associated with a decrease in the rate of negative appendicectomy.

Validation of the AIR and Alvarado scores in a large international cohort will determine the suitability of using these to stratify patients in to low, medium and high-risk groups for appendicitis, as envisaged by recent guidelines.9 If these risk scores are found to have poor prognostic properties, it may be possible to develop and validate a new score based on the RIFT dataset. Risk scores may aid junior clinicians’ decision-making and may have a role in avoiding unnecessary operations, reducing the negative appendicectomy rate and improving patient safety.5 Furthermore, validated risk scores may be particularly useful in low resource settings with limited access to diagnostic investigations.

The UK National Surgical Research Collaborative’s member groups have run trainee-led collaborative studies across 99% of the UK’s surgical units,12 delivering large, prospective studies.7 However, as trainees complete their training and become consultants, the sustainability of postgraduate trainee research collaboratives will be dependent on engaging new junior trainees each year. Whereas previous studies undertaken by surgical research collaboratives have been targeted at either senior trainees or medical students, RIFT is the first study aimed at junior specialty trainees (recent graduates). A surrogate marker for the success of RIFT will therefore be successful engagement and mentoring of junior trainees in collaborative research.

Limitations

The RIFT Study Group has made specific efforts to minimise the risk of inherent bias in this observational study. Data will be collected prospectively and patient pathways followed proactively by collaborators, who will often be the frontline clinicians responsible for the patients’ care. Unlike most previous studies which have focused specifically on patients who undergo appendicectomy, RIFT will include all patients presenting with RIF pain or suspected appendicitis, to general surgical services. Nonetheless, since these patients will have already been triaged by emergency department or general practice doctors, this is likely to be a selected group who are more likely to have appendicitis than patients with truly undifferentiated presentations.

Given the large volume of patients presenting with RIF pain and the short inpatient stays that most patients have reliably identifying all eligible patients will be more challenging than in previous studies run by trainee collaboratives. However, preplanned validation by an independent investigator will ensure that case ascertainment rates are monitored. This will also mitigate any risk of reporting bias from clinicians declining to submit details of patients that have been misdiagnosed at their centre.

*Due to the pragmatic ‘snap-shot’ nature of this study, carried out by practising clinicians, there is a limit to the depth and breadth of data points included. For instance, the study will not collect the length and nature of perioperative antibiotic treatment (table 1). Furthermore, follow-up is limited to 30 days after the index hospital admission. It is possible that a proportion of patients initially discharged having not undergone appendicectomy may subsequently be readmitted and undergo surgery either at other hospitals or beyond the 30-day follow-up.

In summary, the RIFT study is a protocol-driven, international, multicentre prospective observational study using a ‘snap-shot’ methodology, in line with the UK surgical research collaborative model. The study aims to describe the current variation in investigation and management of right iliac fossa pain in several European countries, aligned to contemporaneous specialty guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @WMRC_UK

Contributors: Conception and writing of protocol: Jacob H Matthews, Gabriella L Morley, Shivam Bhanderi, Sarus Jain, Imran Mohamed, Thuvarahan Amuthalingam, Robert Tyler, James C Glasbey, Richard Wilkin, Dmitri Nepogodiev, Aneel Bhangu. Participation in collaborator meeting, development of study concept and editing of protocol: Jacob H Matthews, Gabriella L Morley, Shivam Bhanderi, Sarus Jain, Imran Mohamed, Thuvarahan Amuthalingam, Robert Tyler, James C Glasbey, Ewen Griffiths, Thomas Pinkney, Oliver Gee, Dion Morton, Francesco Pata, Gianluca Pellino, Valeria Farina, Laura Gavagna, Pietro Maria Naccari, Sandro Pasquali, Bruno Sensi, Alessandro Sgrò, Andrea Simioni, Ruth Blanco-Colino, Matteo Frasson, Antonio Sampaio Soares, Natalie Blencowe, Will Bolton, Stephen Chapman, Catherine Bradshaw, Grant Harris, James B Haddow, Kapil Sahnan, John Mason, Scott McCain, David Milgrom, Saleem Noor Mohamed, James O’Brien, Jack Pearce, Mohammed Rabie, Gaël R Nana, Panchali Sarmah, Nigel Jamieson, Richard Wilkin, Dmitri Nepogodiev, Aneel Bhangu. Guarantor: Aneel Bhangu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: In the United Kingdom this observational study does not require research ethics approval. The study will be registered as a clinical audit in each participating UK centre. National leads in the other participating countries will ensure appropriate registration and study approval in compliance with local regulations;, this may require full ethical review in some jurisdictions. Local investigators are responsible for ensuring local approvals are in place.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: WMRC Collaborating members are listed in the online supplementary appendix 1.

References

- 1. Royal College of Surgeons and Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. Commissioning guide 2014: emergency general surgery (acute abdominal pain). London, 2014. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/./commissioning-guide-egs-published-v3.pdf (accessed on 1 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhangu A, Søreide K, Di Saverio S, et al. Acute appendicitis: modern understanding of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 2015;386:1278–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00275-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg 2008;32:1843–9. 10.1007/s00268-008-9649-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med 1986;15:557–64. 10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80993-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kularatna M, Lauti M, Haran C, et al. Clinical Prediction Rules for Appendicitis in Adults: Which Is Best? World J Surg 2017;41:1769–81. 10.1007/s00268-017-3926-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhangu A, short Sof; United Kingdom National Surgical Research Collaborative. Safety of short, in-hospital delays before surgery for acute appendicitis: multicentre cohort study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2014;259:894–903. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Surgical Research Collaborative. Multicentre observational study of performance variation in provision and outcome of emergency appendicectomy. Br J Surg 2013;100:1240–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baird DLH, Simillis C, Kontovounisios C, et al. Acute appendicitis. BMJ 2017;357:j1703 10.1136/bmj.j1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, et al. WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg 2016;11:34 10.1186/s13017-016-0090-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis. EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc 2016;30:4668–90. 10.1007/s00464-016-5245-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhangu A, Kolias AG, Pinkney T, et al. Surgical research collaboratives in the UK. Lancet 2013;382:1091–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nepogodiev D, Chapman SJ, Kolias AG, et al. On behalf of the National Surgical Research Collaborative). The impact of research collaboratives in the UK. Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017;2:247–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatri C, Chapman SJ, Glasbey J, et al. Social media and internet driven study recruitment: evaluating a new model for promoting collaborator engagement and participation. PLoS One 2015;10:e0118899 10.1371/journal.pone.0118899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495–9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017574supp001.pdf (64.7KB, pdf)