Abstract

Objectives

Research focussing on the impact of suicide bereavement on family members’ physical and psychological health is scarce. The aim of this study was to examine how family members have been physically and psychologically affected following suicide bereavement. A secondary objective of the study was to describe the needs of family members bereaved by suicide.

Design

A mixed-methods study was conducted, using qualitative semistructured interviews and additional quantitative self-report measures of depression, anxiety and stress (DASS-21).

Setting

Consecutive suicide cases and next-of-kin were identified by examining coroner’s records in Cork City and County, Ireland from October 2014 to May 2016.

Participants

Eighteen family members bereaved by suicide took part in a qualitative interview. They were recruited from the Suicide Support and Information System: A Case-Control Study (SSIS-ACE), where family members bereaved by suicide (n=33) completed structured measures of their well-being.

Results

Qualitative findings indicated three superordinate themes in relation to experiences following suicide bereavement: (1) co-occurrence of grief and health reactions; (2) disparity in supports after suicide and (3) reconstructing life after deceased’s suicide. Initial feelings of guilt, blame, shame and anger often manifested in enduring physical, psychological and psychosomatic difficulties. Support needs were diverse and were often related to the availability or absence of informal support by family or friends. Quantitative results indicated that the proportion of respondents above the DASS-21 cut-offs respectively were 24% for depression, 18% for anxiety and 27% for stress.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals’ awareness of the adverse physical and psychosomatic health difficulties experienced by family members bereaved by suicide is essential. Proactively facilitating support for this group could help to reduce the negative health sequelae. The effects of suicide bereavement are wide-ranging, including high levels of stress, depression, anxiety and physical health difficulties.

Keywords: mixed-methods, suicide bereavement, family members, morbidity, health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study addressed a specific knowledge gap by examining the physical and psychological health effects of suicide bereavement on family members in Ireland.

The study covered consecutive cases of suicide, which increases the external validity of the outcomes.

This study screened open verdict deaths with validated screening criteria to identify probable suicides. Therefore, this study benefits from the inclusion of probable suicide cases that would otherwise have not been included in the study.

Physical health issues were self-reported and were not objectively measured.

Introduction

Suicide is a significant global concern, with approximately 800 000 people taking their own lives every year.1 For every death by suicide, an estimated 60 people are directly and intimately affected.2 Recent research also indicates that 1 in 20 people have been exposed to suicide in the past year, and 1 in 5 people have been exposed to suicide during their lifetime.3 Suicide bereavement is associated with a host of adverse mental health outcomes, including heightened risk of suicide,4–6 attempted suicide,6–9 depression,10 11 psychiatric morbidity7 and psychiatric admission.11 There is also emerging evidence from quantitative studies that family members bereaved by suicide experienced more physical health issues than those bereaved by other means.12

Individuals bereaved by suicide had poorer general health,13 14 reported more pain,14 reported more physical illnesses15 and disorders including cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension and diabetes.11 In addition, suicide-bereaved family members visited a GP more often15 and had significantly higher rates of outpatient physician visits for physical illnesses11 than non-suicide bereaved individuals. Negative health outcomes provide an impetus for timely access to effective health services and psychosocial supports for those bereaved by suicide, many of whom may carry existing health adversities prior to the death.11

Previous research has underlined the broader importance of access to support for those bereaved by suicide.16 17 In the aftermath of suicide, feelings of depression, anxiety, guilt, extreme sadness, anger and nightmares are often present and are associated with help-seeking in people bereaved by suicide.18 19 These acute effects can be long-lasting: the time point rated as the worst stage after a death is the first week for about one-quarter of suicide-bereaved individuals but many family members struggle with the loss for the first year and, in one-fifth of cases, up to and beyond 3 years.17 Both formal professional support and informal support from friends, families and others are important during this time and address different needs20–22 and may be especially important for first-degree relatives.23 Despite their acute needs, those bereaved by suicide are less likely than other bereaved individuals to receive informal support and immediate support following the death and are more likely to experience a delay in receiving support.17

Although a significant number of quantitative studies have examined the associations among suicide bereavement, physical health outcomes and access to support, these areas have rarely been examined from an experiential perspective using qualitative research in a general sample.24 25 Researchers are beginning to identify the need for further qualitative research on suicide bereavement,26 to take into account the inherent complexity of grieving and social processes.27 Qualitative research can help to elucidate the lived experience of suicide bereavement, highlighting such areas as feelings experienced by those bereaved by suicide, the meaning-making process following bereavement and the social context.28

The primary aim of this research is to examine how people have been physically and psychologically affected by a family member’s suicide. A secondary objective of the study is to describe the support needs required by family members bereaved by suicide. The current mixed-methods approach benefits from leveraging the advantages of both quantitative and qualitative methodological approaches,29 while being able to provide a more comprehensive and in-depth consideration of the research problem under investigation.30

Methods

Study design and setting

This study applied a mixed-methods approach. The qualitative study was linked to a larger case-control study, the Suicide Support and Information System: A Case-Control Study (SSIS-ACE, January 2014–March 2017). Qualitative interviews were supplemented with quantitative data of suicide-bereaved family members’ well-being, which was collected as part of the larger case-control study. Further information on the study design has been reported elsewhere31 and is available in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2017-019472supp001.pdf (757.2KB, pdf)

Sample and recruitment

Qualitative study

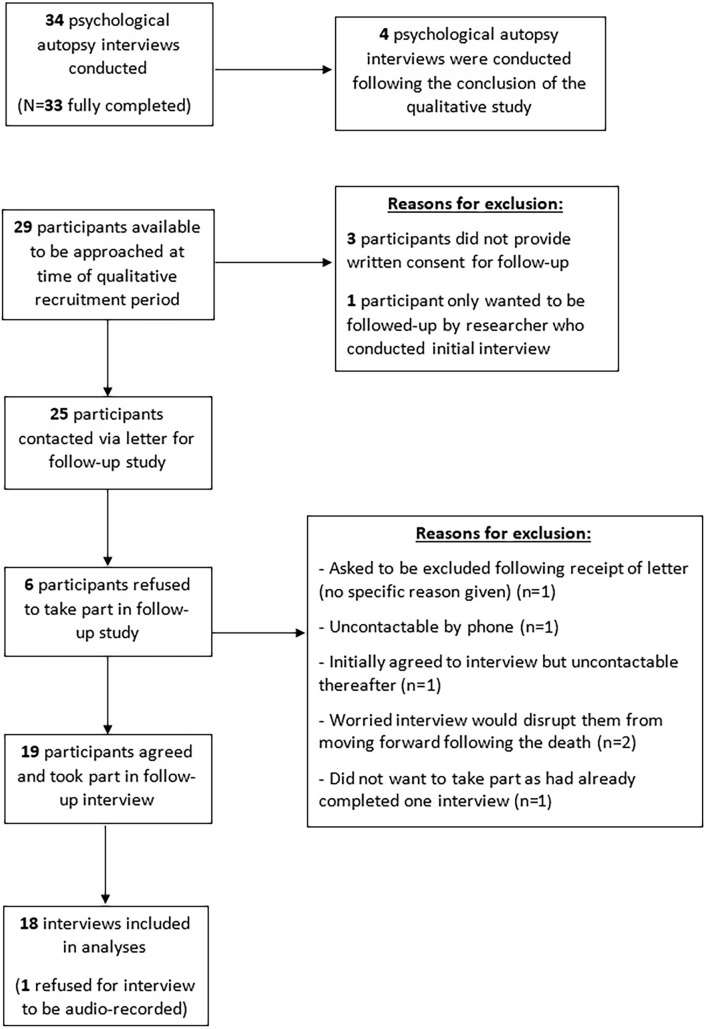

A subset of the 33 participants over the age of 18 who took part in the SSIS-ACE study and who consented for further follow-up were approached to take part in the qualitative study. At the time of the qualitative study recruitment, there were 29 participants in the larger study to sample from. Three of these did not provide written consent for further follow-up and one only wanted to be contacted again by the researcher that conducted the initial psychological autopsy interview. Therefore, 25 individuals were initially contacted via a letter. Nineteen participants agreed to the interview but one participant did not consent for the interview to be audio-recorded and was therefore excluded from the qualitative analysis. This yielded a response rate of 76%. Therefore, 18 interviews were conducted (female=11, male=7). In one instance, two family members were interviewed together at their request. No repeat interviews were conducted. Interviewees were a spouse (n=7), a parent (n=5), a sibling (n=2) and a child (n=4). Full details of the recruitment process are illustrated in figure 1. Mean time since bereavement during the qualitative interviews was 27.6 months (range: 15–38 months). Half of all family members interviewed (n=9) found the deceased’s body, while the other half (n=9) were informed of the death by other family members or a member of the police force.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of recruitment process for the SSIS-ACE study and qualitative study

Quantitative study

The quantitative data outlined in this paper was collected as part of a larger case-control study (SSIS-ACE). In SSIS-ACE, a senior researcher reviewed records of consecutive suicides and open verdict files from inquests held by all coroners in Cork, Ireland over a 19-month period. Open verdict files that met the Rosenberg criteria32 for the determination of suicide32 were eligible for inclusion in the study as probable suicides.31 Relatives were eligible to participate in an interview for the case-control study if they were well-acquainted enough with the deceased to provide detailed information with respect to the deceased’s life and were over the age of 14 years. Family members were contacted by letter and then by telephone and invited to participate in the psychological autopsy interview. ‘Psychological autopsy’ is a specific research method which involves retrospectively collecting information on aspects of a suicide decedents life, including sociodemographics, previous self-harm, mental health, physical health, personality traits and treatment provided by healthcare professionals before the suicide.33 This information is primarily gathered via structured interviews with family or friends of the deceased and also information obtained by health professionals who treated the deceased.33 The study took into account elements of the psychological autopsy approach according to Conner and colleagues.34 Thirty-four family members agreed to take part but one interview was not fully completed and was excluded from analyses. Therefore, full interviews were completed with 33 family members (44%). This response rate is similar to other psychological autopsy studies.35 36 The mean time since bereavement during the psychological autopsy interviews was 10.2 months (range: 6–21 months).

Measures

Qualitative study

Semistructured interviews (n=18) were conducted with the aid of a topic guide31 in order to explore the experiences of people bereaved by the suicide. Interviews began by asking participants about the relationship they had with the deceased. The physical and emotional impact of the bereavement on them was then explored. The impact of the bereavement on the family and their social life was then explored. In addition, participants were asked about what support services they received and what they feel suicide-bereaved family members require in the immediate aftermath and the medium and long-term. Participants’ permission to audio-record the interview was obtained. Thirteen interviews took place in the participant’s home, two in university research offices and three at a neutral location selected by participants. All interviews took place in a single session. Mean length of interviews was 97.5 min (range 42–180 min).

Quantitative study

Family members’ well-being was assessed using the 21-item version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21).37 This scale assesses a participant’s well-being in the past week. The scale successfully differentiates between the three affective states while also demonstrating consistency between clinical and non-clinical samples.37 Median scores of depression, anxiety and stress, together with dichotomised variables were presented. Recommended cut-off scores to generate severity level ranges from normal, mild, moderate, severe and extremely severe categories.38 However, due to small numbers in the study, it was not possible to subdivide the sample by these five categories. Therefore, participants who met the criteria for depression, anxiety and/or stress at the levels between mild and extremely severe were collapsed into a category of above the ‘normal’ cut-off and those below these scores were classified as ‘normal’. Scores of ≥10 for depression, ≥8 for anxiety and ≥15 for stress were considered indicative of the presence of depression, anxiety or stress, respectively. These cut-off points have been used previously37 39 and are considered diagnostic indicators of potential diagnoses of depression, anxiety and/or stress.38 40 All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS V.22.

Data analysis

Qualitative study

Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis, which is a flexible method that allows for a variety of ontological and epistemological stances.41 Thematic analysis involves a number of steps, including familiarising oneself with the data, generating initial codes, searching, reviewing and finally, defining themes.41 Two authors (AS and KM-S) coded the data and all stages of coding and development of themes were discussed with the research team. NVIVO 11 software facilitated the organisation of the data. In the absence of standardised guidelines to report mixed-methods research, the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was used and is available in online supplementary file 2.

bmjopen-2017-019472supp002.pdf (150.4KB, pdf)

Quantitative study

Descriptive statistics were used to present information on the age, gender and marital status of the suicide decedents, the method of suicide, if a suicide note was present and if there was a history of self-harm prior to the death. The age and gender of the family members and their relationship to the deceased were also presented using descriptive statistics. The characteristics of those interviewed for the follow-up qualitative study was compared with those who were not interviewed using χ2 and t-tests. Tests of normality indicated that the data were non-normal and therefore non-parametric tests were used. Median scores and IQRs were computed to describe the DASS-21 subscales and total score. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for differences in well-being for males and females and for people bereaved by a hanging or non-hanging suicide.

Results

Qualitative results

The 18 participants interviewed for the qualitative study did not significantly differ from those not interviewed regarding their gender (P=0.42), age (P=0.56), relationship to the deceased (P=0.69), method of suicide (P=0.69), their depression (P=0.49), anxiety (P=0.08), stress (P=0.59) and total score (P=0.28) on the DASS-21 scale. Three main themes were identified from the analysis process: ‘co-occurrence of grief and health reactions’, ‘disparity in supports after suicide’ and ‘reconstructing life after deceased’s suicide’.

Co-occurrence of grief and health reactions

This first superordinate theme has two subordinate themes: ‘immediate grief reactions’ and ‘enduring physical, psychological and psychosomatic health difficulties’. It was apparent throughout the interviews that physical, psychosomatic and psychological health experiences were often tied in with grief reactions, including blame, guilt and extreme sadness. Additionally, reactions were influenced by contextual factors, such as whether the participant found their family members body or whether they were informed of the death by others.

Immediate grief reactions experienced by participants ranged from guilt, blame, shame, sadness and relief. Participants often felt angry, both towards the deceased and also healthcare professionals who cared for the deceased. Conversely, two participants were not angry with their loved one for taking their own lives: one participant felt relieved their family member was no longer suffering psychologically and ‘felt she had escaped, she got out of it’ and revealed it ‘alleviated some of the pressure’ as ‘she was going to get worse and worse’. Feelings of numbness were reported, with some participants not wanting to believe that their loved one was dead. One family member could not believe her sister was dead until she was given the chance to view her body. The delay in receiving the news about the death and viewing the body appears to have been especially difficult for her when acknowledging the death:

‘I went on then for the night like nothing had happened being honest with you, it was just numb and I didn’t want to believe it until I saw it for myself. That was the Wednesday and we didn’t see her until the Friday’ (sibling)

Physical reactions experienced at the immediate point of bereavement included nausea, vomiting, breathlessness, numbness, memory loss and an inability to stand as ‘my legs had just given way’. One participant noted an immediate physical change to their health, as their heart rate escalated on hearing about the death, which resulted in a diagnosis of hypertension the following day:

‘My heart rate went up straight away, through the roof. Actually, I had to see a doctor on [sic] the next day …and I’m on blood pressure control pills since then and I will be probably for the rest of my life’ (sibling)

Other psychosomatic health reactions often noted by participants included physical pain, severe abdominal pains, loss of appetite, low energy levels and an inability to sleep in the immediate aftermath of the suicide. Some participants attributed their low energy levels to ‘the emotion’ and ‘turmoil’ associated with their grieving, while others felt it was due to their disrupted sleeping patterns. Reported problems with sleeping in the immediate aftermath varied in severity and duration. One participant described how they ‘couldn’t sleep at all in the beginning’ and another described how they tried to tire themselves during the day with walks in an attempt to sleep at night. A number of participants described experiencing distressing nightmares and visions of the deceased:

‘The son came in like and he was asking me what I was doing…[deceased] was talking to me, I was talking to him, he was there like, do you know what I’m saying…I thought he was, I was out of my bed and the whole lot’ (parent)

Loss of appetite was reported by some participants as a psychosomatic reaction which often led to weight loss. Reasons for loss of appetite varied, including nausea due to flashbacks of finding the body or feelings of depression and despondence following the death:

‘Food-wise, I’m never hungry, I could stay without it all day…if I have a cup of tea and a bit of bread in the morning, I’m grand…Since himself has gone, you’re just getting up in the morning doing the odd old thing, sure what’s the point in doing it like’ (spouse)

Finding the decedent’s body appeared to induce more severe reactions in some cases which often extended to longer-term psychological impacts, including depression, anxiety, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts.

‘I was depressed afterwards and I…still have this fuzziness in my head…it’s very hard to explain. It feels like I’m stressed, stressed, like even small little things I can’t deal with’ (spouse)

One participant noted that they were not distressed at finding the body but described the scene as ‘calm’, while also providing her with the opportunity to say goodbye to the deceased. It also allowed her to lay ‘down on the ground beside him and I put my head down on his chest…he was still warm and everything…I just stayed there for a long…I suppose it was my way of saying goodbye to him’ (sibling).

The initial experiences of the majority of family members bereaved by suicide set the stage for enduring physical, psychological and psychosomatic difficulties in the months following the bereavement. First, a number of adverse mental health outcomes were reported by family members including being more concerned about their own mental health, experiencing suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, depression, anxiety and physician-diagnosed PTSD in the months after the death. Nightmares, memory loss and intrusive images of the deceased were often present. One participant attempted suicide in the months after the suicide but emphasised they did not want to die but rather to escape the emotional pain and depression:

‘The morning that it happened, I just woke up and the feeling was so awful just inside my head, I thought like I just can’t stick this anymore, so that’s why I done [sic] it. It was just like to get away from this awful feeling’ (sibling)

Ongoing intrusive images of the deceased and how they died were also reported by a number of participants. These images were not restricted to those who found the body but were also experienced by those who were informed of the death by others. One participant was preoccupied with the violent and traumatic nature of the death which resulted in her still being unable to sleep at night:

‘I’d be awake all night…and then I’m wrecked during the day. In the dead of night in the dark I think about how she done [sic] it…that would make me ill’ (parent)

Additionally, a number of participants reported psychosomatic symptoms including chronic feelings of low energy/exhaustion, persistent chest pains, breathlessness and physical pain which endured in the months after deceased’s death. Their health status was often influenced by their health behaviours. Some family members noted ‘everything stopped, the world stopped that day’ and tried but failed to resume their normal physical activity. For others, negative health behaviours including excessive alcohol consumption and overeating were used as a coping mechanism:

‘I’d drink I’d say [pauses] a bottle of vodka a day and a few pints as well… it’s [the alcohol consumption] got a bit worse… I don’t know if it’s directly related to it or whether I’m using it as an excuse’ (parent)

Importantly, some family members experienced an improvement in health behaviours, including increasing their levels of physical activity which benefited fitness levels, healthy weight loss and aided the grieving process:

‘I went out to the dancing on a Wednesday night, I said make new friends you know…ya I’ve got fitter… That was a big boost for me to chat to people and pass away the week’ (spouse)

Participants experienced a number of adverse physical health problems in the months after the deceased’s suicide, including being diagnosed with hypertension, type 1 diabetes and diverticulitis. Participants attributed these diagnoses to the stress of the deaths:

‘I was hospitalised again this week with it…the doctor came in and said “you need to stop, you really need to stop, it’s not cancer but it’s going to affect you for the rest of your life…I know that’s a consequence of dealing with [deceased’s death]” ‘ (child)

Disparity in supports after suicide

The second superordinate theme has two subordinate subthemes: ‘need for formal support’ and ‘need for informal support’. Participants described requiring a range of supports; however, these needs were often not fully addressed by the formal and informal support networks. This disparity in the needs and availability of support impacted on the participant’s grieving process. Primarily, both formal and informal support were required to address intense psychological, psychosomatic and physical symptoms brought about by feelings of anger, guilt and blame:

‘I went to a bereavement information evening one night before I started any counselling, they put up on a screen physical symptoms and there was about 20 different things and I could tick at least 10 of them, shortness of breath, panic attacks, headaches, chest pains, physical chest pains…crippling abdominal pains…it’s the anger that manifests itself in physical pain’ (spouse)

Informal support, in the form of practical and emotional support from family and friends, was as important as formal support to some participants. One participant described how ‘every night for so long my parents came over to stay every night’, while another credited his wife as ‘the biggest support that I have received’. He went on to say that if he was ‘just left to wallow in it’, that he ‘would have gone into a big black hole over it’. Another participant emphasised the importance of both informal and formal support following a suicide:

‘The love of my family…“come home, we’ll mind you” and they did, that was incredible and if some poor person doesn’t have that, I really pity them. It’s your family and your friends that gets you through that, and the counselling’ (spouse)

Others described how family and friends helped with funeral arrangements, financial support, preparing or bringing food to the family member and helping with practical jobs around the house, such as maintaining the house and garden in the weeks and months after the death:

‘My friends from down the town would come up every day with food and I would always forgot they were going to do it [laughs] so they were coming up for about a month with food, they were so kind… I was embarrassed but I found it helpful’ (spouse)

In some instances, fractured family relations impeded the family member receiving informal support. In those instances, the importance of formal support is paramount:

‘I have a sister but then we fell out over this, I don’t have any contact with them…My problem is if I was feeling down, I wouldn’t say it to them… [I’d be] very wary of people because I’ve said things and it’s gone around town…I know I can trust my counsellor or my doctor or yourself there now’ (spouse)

Another participant sought formal support as they ‘needed to speak to somebody outside of my family because I was upsetting everybody when I wanted to talk’. Seeking formal support was imperative ‘to get the counselling, just taking time to reflect on everything and deal with it’. Two participants noted respectively that there was ‘no pressure with money’ from the counsellor and if they didn’t have ‘the money that day she’d say give it to me when you have it’. A number of participants spoke about having to stop formal support due to financial reasons, with one participant stating that there ‘should be free counselling for people bereaved by suicide’:

‘I hadn’t any steady money coming in, my illness benefit had finished and stuff like that…So that’s the reason I finished up with him [counsellor]’ (spouse)

The understanding and flexibility of some bereavement counsellors following the suicide were hugely valued by participants. However, not all experiences with formal support were positive, with one person noting that the counsellors were ‘too shocked to deal with me’, while another said the counsellor ‘had the clock ticking’. Participants noted that nobody proactively contacted them to offer formal support. This point is particularly salient as many spoke of being unable to seek help themselves or were unsure of what help was required. Feeling ‘so awful’ and ‘you don’t even know what you need’ were significant barriers to seeking help while others had to ‘make the phone calls’ and ‘run after all of them [the counselling services]’. One participant spoke about how she did not approach her own GP for help ‘but he never came with a list of things either to see how I was either, here’s a list of services you can avail of’. She expected him to contact her and she explained ‘it’s very hard yourself because you don’t even know what you need’. As a result, she was searching the internet ‘to find anything’ and spoke about how ‘things aren’t readily available I think in this day and age even though mental health is a really important thing’.

Some participants wanted to attend a suicide bereavement support group as they felt counsellors could not ‘possibly understand what’s going on in my head, like unless they’ve been through it’. Others spoke of wanting to talk to others ‘with similar experiences’ because ‘I think it’s important for me to feel that I’m not the only one going through this’. Additionally, one participant felt that she would benefit from it ‘because I do find I’m alone in my thoughts of it and I’m interested in getting other peoples stories so I can relate [to it]’. However, no such support groups were available for any of the participants. A small number of participants reported that they did not require any formal support. One participant spoke with their husband about whether they needed counselling and both concluded that they can ‘hack this’ on their own. Specifically, two participants who noted they did not require formal support were engaging in overeating and excessive alcohol consumption as coping mechanisms.

Reconstructing life after deceased’s suicide

Each participant was confronted with trying to comprehend, make sense of and reconstruct aspects of their lives following their family member’s suicide. Participants were particularly concerned with aspects of their well-being. Some spoke about finding it difficult to look positively to the future. Some participants spoke about moving forward in terms of relationships. One participant spoke about how ‘he [the deceased] was the person I was supposed to spend the rest of my life with and looking to the future without him is…it’s hard for me to do’. She explains how people often say to her ‘you’re young, you’re going to find someone else…and have more kids’. However, she feels ‘that’s not for me now… I feel like I had that experience with him, and I feel like I don’t want that with anyone else ever’. Some participants spoke about seeking new relationships following their partner’s death. One participant spoke about how her friends and her counsellor broached the topic of a new relationship with her and she felt ‘why not…I have an awful lot of love to give’. Seeking new relationships and friendships was an important aspect of moving forward for some participants as ‘there was lots of times where I wouldn’t go out…but eventually I got it into my head, I went out to the dancing on a Wednesday night, I said make new friends…and then I met this new girl last year before Christmas’.

In terms of well-being, a small minority of participants were unable to experience positive thoughts following the suicide. One spoke about wondering ‘what’s the point in living…that’s what’s killing me’. Another participant spoke about she no longer socialises since her partner’s death and becomes depressed following constant rumination about his death:

‘I don’t socialise the way I used to before with other people…the tv might be on but I’d have no interest, I’d be just thinking away to myself and get depressed about it then’ (spouse)

Conversely, the majority of participants spoke about how while they had negative thoughts, they were often able to balance these with more positive thoughts. One participant noted that simple things like turning on the radio so there’s ‘something on in the house’ or watching a DVD with his children helps as he ‘enjoys it when we’re all together’. Various other social activities and past-times such as walking and gardening were endorsed by some as helping during the grieving process. One participant spoke about how she uses yoga as a means of ‘being present’ and to tell herself that she’s ‘ok’ even when ‘there are still images in my head’ after finding the deceased. A further participant stated they were ‘very positive’ and engaged in walking and ‘a bit of photography’ which helped him in ‘hanging together fairly well’.

Part of this reconstruction was also about reappraising what was important to them and how they thought about life. Some participants chose to make big life changes after the death, including moving homes, changing jobs or completely disengaging from the work environment:

‘I haven’t gone back to my old job in [big city], you know life has changed and I was working long days and didn’t really have a life, now, I’m looking back and saying, there’s a little bit more to life than that you know?’ (spouse)

Two participants moved house soon after the death. One described that she ‘couldn’t stay there’ as the death occurred in the house. The other participant was forced to sell the house to pay off the debts the deceased had accumulated but had hidden from his partner. The participant felt a sense of rejection and betrayal that the deceased did not trust her enough to speak to her about their spiralling debts. She would have ‘toughed it out and said to him ok what are we going to do about it’ but she feels he was afraid to tell her as ‘I suppose he thought I’d leave him’. Three participants were in the process of selling their properties or had a strong desire to move at the time of the interview as one felt she could not ‘move forward while I’m in this house presently’ due to her experience of visions of the deceased in the house.

Quantitative results

Characteristics of decedents and family members

Characteristics of the 33 suicide decedents and family members bereaved by suicide are presented in table 1. The majority of suicide decedents were male (72.7%), aged 40–59 years (42.4%), were single (42.4%) at the time of death and died by hanging (57.6%). While just over half of the suicide-bereaved family members were female (54.5%) and aged between 40 and 59 years (57.6%). The most commonly represented kinship was partner/spouse (36.4%). The majority of suicide decedents were educated to secondary school level (39.4%), followed by one-quarter (27.3%) and one-fifth (21.2%) were educated to post-leaving certificate and third level, respectively. The majority of suicide decedents (42.4%) were employed/self-employed prior to their death. Data for the other educational and employment categories were not presented to maintain confidentiality. Hanging was the most common method of suicide (57.6%), with over half of the sample having a history of intentional self-harm prior to their suicide (54.5%). Just under a half of suicide decedents (45.5%) left a suicide note.

Table 1.

Characteristics of suicide decedents and suicide-bereaved family members (n=33)

| Suicide decedents, N (%) | Family members, N (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 (72.7) | 15 (45.5) |

| Female | 9 (27.3) | 18 (54.5) |

| Age | ||

| 18–39 years | 9 (27.3) | 7 (21.2) |

| 40–59 years | 14 (42.2) | 19 (57.6) |

| 60+ years | 10 (30.3) | 7 (21.2) |

| Interviewee’s relationship to deceased | ||

| Partner/Spouse | 12 (36.4) | |

| Parent | 7 (21.2) | |

| Sibling | 9 (27.3) | |

| Child | 5 (15.2) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 14 (42.2) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 12 (36.4) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 7 (21.2) | |

Well-being outcomes (DASS-21 scale)

Median scores on the DASS-21 were highest for stress (median=12.00, IQR=11.00), followed by depression (median=4.00, IQR=8.00) and anxiety (median=2.00, IQR=5.00). Nearly one-quarter of the sample (24.2%) had scores that indicated the presence of at least mild levels of depression. One in four suicide-bereaved family members (27.3%) had scores that indicated the presence of at least mild levels of stress. Just under a fifth of participants (18.2%) had scores that indicated the presence of at least mild levels of anxiety (table 2). These outcomes refer to participants’ well-being in the week before the interview.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of DASS-21 scale scores

| Median (IQR) | Range | Above ‘normal’ cut-off, N (%)* | |

| Depression score | 4.00 (8.00) | 0–34 | 8 (24.2) |

| Anxiety score | 2.00 (5.00) | 0–24 | 6 (18.2) |

| Stress score | 12.00 (11.00) | 0–28 | 9 (27.3) |

| Total score | 18.00 (26.00) | 0–76 |

*Scores of ≥10 for depression, ≥8 for anxiety and ≥ 15 for stress.

DASS-21, 21-item version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale.

A Mann-Whitney U test revealed no significant difference in the levels of depression (P=0.47), anxiety (P=0.37) and stress (P=0.81) between suicide-bereaved males and females (table 3). A Mann-Whitney U test also revealed no significant differences for levels of depression (P=0.43), anxiety (P=0.45) and stress (P=0.61) between those bereaved by hanging and non-hanging suicides (table 3).

Table 3.

DASS-21 median rank scores by gender and method of suicide

| Males (n=15) Median (IQR) |

Females (n=18) Median (IQR) |

P value | Hanging (n=19) Median (IQR) |

Non-hanging* (n=14) Median (IQR) |

P value | |

| Depression score | 4.00 (10.00) | 4.00 (7.00) | 0.47 | 4.00 (6.00) | 4.00 (13.00) | 0.43 |

| Anxiety score | 2.00 (2.00) | 3.00 (14.00) | 0.37 | 2.00 (6.00) | 2.00 (6.00) | 0.45 |

| Stress score | 12.00 (12.00) | 11.00 (11.00) | 0.81 | 10.00 (10.00) | 13.00 (13.00) | 0.61 |

| Total score | 18.00 (26.00) | 18.00 (32.00) | 0.93 | 18.00 (14.00) | 19.00 (29.00) | 0.74 |

*Includes every other method besides hanging.

DASS-21, 21-item version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale.

Discussion

Principal findings

The qualitative and quantitative aspects of this study provides insight into the unique grief processes and health impacts experienced by family members bereaved by suicide. The qualitative study further addresses a significant gap in the literature by exploring the physical, psychosomatic health experiences and health behaviours of suicide-bereaved family members. Results from the quantitative component of this study indicate that a sizeable minority of suicide-bereaved family members experienced elevated levels of depression, anxiety and stress. Other empirical studies have found similar rates of depression and anxiety among suicide-bereaved people to the current study, with one study finding that 18% of the sample were moderately to severely depressed, as measured on the PHQ-9, while 21% reported anxiety symptoms on the GAD-2.42 Furthermore, the prevalence of depression in family members bereaved by suicide was reported in previous studies as 30.5%11 and 23%.43 Other studies of non-clinical samples of adults had lower median scores on the DASS-21 scale when compared with the suicide-bereaved median scores found in this study.44 45 Therefore, this indicates that those bereaved by suicide may have higher rates of depression, anxiety and stress compared with non-clinical adult samples.

One possible explanation for the lower than expected prevalence of depression, anxiety and/or stress in our sample may be selection bias. Those family members who chose to take part in the study may have had lower levels of psychopathology or difficulties with the grieving process than other bereaved family members and therefore may have been more likely to take part in the study. One recent population-based study compared suicide-bereaved parents with matched non-bereaved parents: 20.5% of suicide-bereaved parents refused to take part or to complete the study on the grounds of distress or ill-health, compared with just 7.6% of non-suicide bereaved parents.42 This suggests that those who agree to take part in suicide bereavement research may be in better health than those who declined to participate. Consequently, the number of suicide-bereaved people experiencing high levels of depression, anxiety and/or stress in this study and other empirical research may be an underestimate of the true figure. Findings from the qualitative interviews indicate that the initial feelings experienced by family members bereaved by suicide include disbelief, shock, blame, guilt and anger. These mirror findings from other qualitative studies.28 Our qualitative and quantitative results indicate that suicide-bereaved family members experience a number of adverse psychological problems including depression, anxiety, panic attacks, suicidal thoughts, intrusive images, nightmares and PTSD. In addition, a number of participants also experienced adverse psychosomatic health experiences including feelings of nausea, vomiting, chest pains, palpitations, physical pain, abdominal pains and breathlessness. In some cases, these symptoms continued in the months after the death and were associated with diagnoses such as hypertension, diverticulitis and type 1 diabetes. Bolton and colleagues11 took a quantitative approach and similarly found that suicide-bereaved parents had significantly higher rates of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, diabetes, depression and anxiety disorders compared with accident-bereaved parents. Additionally, a recent systematic review noted that there is tentative evidence to suggest that suicide-bereaved family members have an increased risk for a number of adverse physical health outcomes compared with people bereaved by other causes of death.11 13–15 46 Therefore, this study corroborates these previous findings that people bereaved by suicide can experience adverse physical and psychological health outcomes.

The quantitative and particularly the qualitative component of this study illustrate the difficulties encountered by family members bereaved by suicide and consequently, the support they require. Research compiled by Grad and colleagues47 underlies the importance of those bereaved by suicide having the opportunity to seek support from outside the family. Some participants spoke of the desire to attend a suicide support group. However, there is little research on the effectiveness of these groups for those bereaved by suicide.48 It was also clear from the interviews that financial difficulties in the aftermath of the suicide were unfortunately common and prevented many from accessing formal support services. Participants spoke about having to halt their counselling sessions due to a lack of money to pay for the service. Reasons for financial difficulties varied and included inheriting debts accrued by the deceased prior to the death or having to give up or take a break from work due to grieving difficulties. Another study found that duration of support was important, with 27% of people believing they required professional help for at least 12 months following the death. Furthermore, 25% and 17.4% reported needing support for at least 2 years or for as long as required.23 These points underlie the importance of providing timely and effective support to people bereaved by suicide and support that does not preclude people due to their financial circumstances.

The findings from the semistructured interviews corroborate the quantitative results of family members’ well-being, as measured by the DASS-21 scale. The quantitative scale found that nearly one-quarter of family members had scores that indicated at least mild levels of depression. Furthermore, one in four and nearly one in five had a least mild levels of stress and anxiety, respectively. The qualitative interviews provided a greater insight into these difficulties through participants’ descriptions of visions/nightmares, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and physician-diagnosed depression, anxiety and PTSD in the months following the suicide. Additionally, this mixed-methods study identified a gap in the literature relating to qualitative research specifically exploring the physical and psychosomatic health experiences in family members bereaved by suicide. Going forward, further quantitative research investigating the association between suicide bereavement and objective measures of physical health is required.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first mixed-methods study to specifically examine and explore the physical and psychological health implications of suicide bereavement from both a quantitative and a qualitative perspective. The mixed-methods approach and the comprehensive recruitment process involved is a key strength of this study. The quantitative data for this study were derived from the larger SSIS-ACE case-control study which included consecutive cases of suicide and open verdict cases that met the Rosenberg criteria for the determination of suicide which were identified via examining coroner’s records.32 Basic information about the case and next-of-kin information was collected. Family members were initially contacted via letter and telephone to take part in a psychological autopsy study. Data on family members’ well-being were collected at the end of the psychological autopsy interview. These data were analysed and they form the quantitative component of this mixed-methods study. Following their participation in the larger case-control study, those who provided written consent for follow-up were contacted by the first author of this paper to take part in an additional qualitative interview about their experiences following the suicide. Recruitment of the family members via coroner’s records and the consecutive nature of the suicide and open verdict cases reduces the likelihood of selection bias, which is often a significant problem in research addressing vulnerable populations.49 The validity of this research can be considered good as this research covered both confirmed suicide deaths and open verdicts deaths as these may in fact be hidden suicide cases.50–52 Furthermore, researchers have recommended that such cases meeting criteria for a probable suicide should be included in future research studies.51 The combination of quantitative and qualitative research provides a clear indication of the challenges and health problems encountered by family members bereaved by suicide.

While the numbers of suicide-bereaved family members in the study is modest, the quantitative results are similar to those obtained in larger studies, as previously stated.11 43 The interviewer for the qualitative component of the study (AS) did not conduct any of the interviews for the SSIS-ACE study, which minimises the risk of interviewer bias in the mixed-methods study. This study has two main limitations. First, family members’ physical health experiences were self-reported and therefore do not constitute an objective measure. An objective measure of physical health would remove any potential for recall bias in participants’ responses. However, the focus of the qualitative component of the study is to understand family member’s experience of their own health, rather than objective health status. Second, the relatively small quantitative sample size did not allow for more sophisticated statistical analyses, including controlling for potential confounding factors such as closeness to the deceased, kinship and time since death which may have impacted on the results presented. Further mixed-methods research examining an objective measure of physical health would be a significant addition to the knowledge base.

Implications

Considering previous research in the area, this study adds to the existing knowledge-base in a number of ways. While the mental health outcomes of suicide bereavement have been well-researched, there has been a dearth of research specifically examining the physical and psychosomatic health outcomes of suicide bereavement from an experiential perspective. Several implications arise from this research for professionals seeking to support people bereaved by suicide. First, equal attention needs to be given to the physical and emotional sequelae following suicide bereavement by clinicians. This research suggests that one in four people bereaved by suicide will suffer elevated levels of depression and stress and just under one in five will have elevated levels of anxiety. Second, it was clear that, due to mental and physical health difficulties, some people were not able to effectively identify or seek support. This underlies the importance of health professionals, coroners and any other professional to proactively facilitate support for those bereaved by suicide. This professional support is especially important when strained or fractured familial relations affect the quality of the bereaved person’s informal support network.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of those who took the time to take part in the interviews. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr Christina Dillon for her guidance with respect to the quantitative data analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS drafted the initial document. AS, CL, EA and PC contributed to the design of the study. KM-S, CL, PC and EA contributed to planned analyses. KM-S, CL, EA and PC contributed to revising drafts. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was conducted as part of the SPHeRE Programme under Grant No. SPHeRE/2013/1. We would also like to acknowledge the funding received from the Health Research Board to conduct the original SSIS-ACE case-control study, Grant No. HRA-2013- PHR-438 and the National Office for Suicide Prevention for providing funding for the supervision of this research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval has been granted from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of University College Cork, reference number: ECM 4 (o) 19/01/2016. Ethical approval was also granted from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of University College Cork, for the SSIS-ACE study, reference number: ECM 5(5) 01/04/2014.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data recorded, transcribed and analysed are very sensitive in nature. Due to the relatively small number of participants and the specific geographic location, it would not be appropriate to consider data sharing due to the risk of people being potentially identified.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. Preventing suicide: a global imperative: Luxembourg, 2014:89. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman AL. Estimating the population of survivors of suicide: seeking an evidence base. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011;41:110–6. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andriessen K, Rahman B, Draper B, et al. Prevalence of exposure to suicide: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. J Psychiatr Res 2017;88:113–20. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitman A, Osborn D, King M, et al. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:86–94. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70224-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostila M, Saarela J, Kawachi I. Suicide following the death of a sibling: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002618 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitman AL, Osborn DP, Rantell K, et al. Bereavement by suicide as a risk factor for suicide attempt: a cross-sectional national UK-wide study of 3432 young bereaved adults. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009948 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox HC, Kuramoto SJ, Lichtenstein P, et al. Psychiatric morbidity, violent crime, and suicide among children and adolescents exposed to parental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:514–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Rasmussen F, Lange T. A life-course study on effects of parental markers of morbidity and mortality on offspring’s suicide attempt. PLoS One 2012;7:e51585 10.1371/journal.pone.0051585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Rasmussen F, Wasserman D. Familial clustering of suicidal behaviour and psychopathology in young suicide attempters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008;43:28–36. 10.1007/s00127-007-0266-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brent D, Melhem N, Donohoe MB, et al. The incidence and course of depression in bereaved youth 21 months after the loss of a parent to suicide, accident, or sudden natural death. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:786–94. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08081244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolton JM, Au W, Leslie WD, et al. Parents bereaved by offspring suicide: a population-based longitudinal case-control study. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:158–67. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spillane A, Larkin C, Corcoran P, et al. Physical and psychosomatic health outcomes in people bereaved by suicide compared to people bereaved by other modes of death: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017;17:939 10.1186/s12889-017-4930-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyabayashi S, Yasuda J. Effects of loss from suicide, accidents, acute illness and chronic illness on bereaved spouses and parents in Japan: their general health, depressive mood, and grief reaction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;61:502–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01699.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groot MH, Keijser J, Neeleman J. Grief shortly after suicide and natural death: a comparative study among spouses and first-degree relatives. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2006;36:418–31. 10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Séguin M, Lesage A, Kiely MC. Parental bereavement after suicide and accident: a comparative study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1995;25:489–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitman AL, Hunt IM, McDonnell SJ, et al. Support for relatives bereaved by psychiatric patient suicide: national confidential inquiry into suicide and homicide findings. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:appi.ps.201600004 10.1176/appi.ps.201600004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitman AL, Rantell K, Moran P, et al. Support received after bereavement by suicide and other sudden deaths: a cross-sectional UK study of 3432 young bereaved adults. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014487 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettersen R, Omerov P, Steineck G, et al. Suicide-bereaved siblings’ perception of health services. Death Stud 2015;39:323–31. 10.1080/07481187.2014.946624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMenamy JM, Jordan JR, Mitchell AM. What do suicide survivors tell us they need? Results of a pilot study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2008;38:375–89. 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyregrov K. What do we know about needs for help after suicide in different parts of the world? A phenomenological perspective. Crisis 2011;32:310–8. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyregrov K. Assistance from local authorities versus survivors’ needs for support after suicide. Death Stud 2002;26:647–68. 10.1080/07481180290088356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown J, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, et al. Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:275 10.1186/s12888-014-0275-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson A, Marshall A. The support needs and experiences of suicidally bereaved family and friends. Death Stud 2010;34:625–40. 10.1080/07481181003761567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugrue JL, McGilloway S, Keegan O. The experiences of mothers bereaved by suicide: an exploratory study. Death Stud 2014;38:118–24. 10.1080/07481187.2012.738765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKinnon JM, Chonody J. Exploring the formal supports used by people bereaved through suicide: a qualitative study. Soc Work Ment Health 2014;12:231–48. 10.1080/15332985.2014.889637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hjelmeland H, Knizek BL. Why we need qualitative research in suicidology. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2010;40:74–80. 10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellenbogen S, Gratton F. Do they suffer more? Reflections on research comparing suicide survivors to other survivors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001;31:83–90. 10.1521/suli.31.1.83.21315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shields C, Kavanagh M, Russo K. A Qualitative Systematic Review of the Bereavement Process Following Suicide. Omega 2017;74:426–54. 10.1177/0030222815612281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers J, Apel S. Revitalizing suicidology: a call for mixed methods designs. Suicidology Online 2010;1:95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spillane A, Larkin C, Corcoran P, et al. What are the physical and psychological health effects of suicide bereavement on family members? Protocol for an observational and interview mixed-methods study in Ireland. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014707 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg ML, Davidson LE, Smith JC, et al. Operational criteria for the determination of suicide. J Forensic Sci 1988;33:12589J–56. 10.1520/JFS12589J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isometsä ET. Psychological autopsy studies-a review. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16:379–85. 10.1016/S0924-9338(01)00594-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conner KR, Beautrais AL, Brent DA, et al. The next generation of psychological autopsy studies. Part I. Interview content. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011;41:594–613. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freuchen A, Kjelsberg E, Grøholt B. Suicide or accident? A psychological autopsy study of suicide in youths under the age of 16 compared to deaths labeled as accidents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2012;6:30 10.1186/1753-2000-6-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong PW, Chan WS, Chen EY, et al. Suicide among adults aged 30-49: a psychological autopsy study in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health 2008;8:147–47. 10.1186/1471-2458-8-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:335–43. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales. 2nd Edition: Sydney Psychology Foundation, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung T, Wong S, Wong K, et al. Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among baccalaureate nursing students in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:779 10.3390/ijerph13080779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkitny L, McAuley J. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). J Physiother 2010;56:204 10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70030-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omerov P, Steineck G, Dyregrov K, et al. The ethics of doing nothing. Suicide-bereavement and research: ethical and methodological considerations. Psychol Med 2014;44:3409–20. 10.1017/S0033291713001670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melhem NM, Walker M, Moritz G, et al. Antecedents and sequelae of sudden parental death in offspring and surviving caregivers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:403–10. 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinclair SJ, Siefert CJ, Slavin-Mulford JM, et al. Psychometric evaluation and normative data for the depression, anxiety, and stress scales-21 (DASS-21) in a nonclinical sample of U.S. adults. Eval Health Prof 2012;35:259–79. 10.1177/0163278711424282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005;44:227–39. 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyregrov K, Nordanger D, Dyregrov A. Predictors of psychosocial distress after suicide, SIDS and accidents. Death Stud 2003;27:143–65. 10.1080/07481180302892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grad OT, Clark S, Dyregrov K, et al. What helps and what hinders the process of surviving the suicide of somebody close? Crisis 2004;25:134–9. 10.1027/0227-5910.25.3.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andriessen K, Krysinska K. Essential questions on suicide bereavement and postvention. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:24–32. 10.3390/ijerph9010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maple M, Cerel J, Jordan JR, et al. Uncovering and Identifying the Missing Voices in Suicide Bereavement. Suicidology Online 2014;5:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pritchard C, Hansen L. Examining undetermined and accidental deaths as source of ‘under-reported-suicide’ by age and sex in twenty Western countries. Community Ment Health J 2015;51:365–76. 10.1007/s10597-014-9810-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bakst SS, Braun T, Zucker I, et al. The accuracy of suicide statistics: are true suicide deaths misclassified? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2016;51:115–23. 10.1007/s00127-015-1119-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang SS, Sterne JA, Lu TH, Th L, et al. ‘Hidden’ suicides amongst deaths certified as undetermined intent, accident by pesticide poisoning and accident by suffocation in Taiwan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:143–52. 10.1007/s00127-009-0049-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019472supp001.pdf (757.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019472supp002.pdf (150.4KB, pdf)