Abstract

Introduction

Generic instruments for assessing health-related quality of life may lack the sensitivity to detect changes in health specific to certain conditions, such as dementia. The Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD) is a widely used and well-validated condition-specific instrument for assessing health-related quality of life for people living with dementia, but it does not enable the calculation of quality-adjusted life years, the basis of cost utility analysis. This study will generate a preference-based scoring algorithm for a health state classification system -the Alzheimer’s Disease Five Dimensions (AD-5D) derived from the QOL-AD.

Methods and analysis

Discrete choice experiments with duration (DCETTO) and best–worst scaling health state valuation tasks will be administered to a representative sample of 2000 members of the Australian general population via an online survey and to 250 dementia dyads (250 people with dementia and their carers) via face-to-face interview. A multinomial (conditional) logistic framework will be used to analyse responses and produce the utility algorithm for the AD-5D.

Ethics and dissemination

The algorithms developed will enable prospective and retrospective economic evaluation of any treatment or intervention targeting people with dementia where the QOL-AD has been administered and will be available online. Results will be disseminated through journals that publish health economics articles and through professional conferences. This study has ethical approval.

Keywords: dementia, quality adjusted life year, discrete choice experiment, best worst scaling, utility weight

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Utility values will be able to be calculated for any treatment or intervention targeting people with dementia where the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s disease has been administered.

Preference value sets from both general population and dementia dyads will be modelled and compared.

The study has a broad range of investigators with input in the design from consumers and aged care organisations.

The valuation methods used may not be readily understood by people with dementia, thereby limiting the ability to value quality of life from their own perspective.

The ability of the study to generate specific algorithms for people with dementia and their carers will be impacted if recruitment targets are not met.

Introduction

Economic evaluation has become widely used as a method for assessing the value for money of health intervention programmes in Australia and overseas.1 The most prevalent form of economic evaluation is cost utility analysis, which compares interventions in terms of their incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The QALY is a single measure of outcome that takes into account both quantity of life (survival) and health-related quality of life (morbidity). The measurement of QALYs relies on a single preference-based index measure of health: a utility weight.

There are a large number of health-related quality of life instruments available to derive utility weights. The most frequently used are generic instruments suitable for any health condition; however an increasing number of condition-specific instruments are available. All preference-based measures have two common elements: a health state classification system that can be used to categorise all patients with the condition of interest and a means of obtaining a utility score for all states defined by the classification system.2

Previous studies assessing the health of people with dementia have used both generic (the 15-Dimensions,3–5 Assessment of Quality of Life,6–8 Quality of Well-being,9–11 Health Utilities Index,12–14 EuroQol-5-Dimensions (EQ-5D))15–17 and disease-specific (Dementia Quality of Life - Utility - (DEMQOL-U))2 18 19 preference-based instruments. Generic instruments are regularly recommended by health technology assessment organisations and regulatory authorities on the basis that they facilitate comparisons across different health conditions and diseases,20 thus addressing the health system’s objective of allocative efficiency. However, generic instruments may lack the coverage to detect change in important aspects of certain conditions. For example, the five dimensions of EQ-5D lack attributes to capture cognition21 and relationships with family and social support22 that are important domains in measuring the quality of life of people with dementia. Those limitations have motivated the recent development of the DEMQOL-U, a preference-based instrument generated from the DEMQOL, a dementia-specific quality of life instrument.23 However, the DEMQOL-U’s use for people with dementia may be limited because it does not directly measure physical health dimensions18 and is time consuming to complete.24

Our team has recently developed a new health state classification system, the alzheimer’s disease five dimensions (AD-5D)25 based on the QOL-AD nursing home version.26 The QOL-AD, originally developed for people with dementia living in the community,27 is the quality of life measure for people with dementia recommended in European guidelines due to its brevity, validity and wide usage.28 The AD-5D development process involved the use of statistical methods (psychometric, factor and Rasch analyses) to identify five key dimensions (‘memory’, ‘mood’, ‘physical health’, ‘living situation’ and ‘do things for fun’) and subsequently select items to represent the dimensions and generate the health state classification system. These five items appear in both QOL-AD nursing home and community versions.

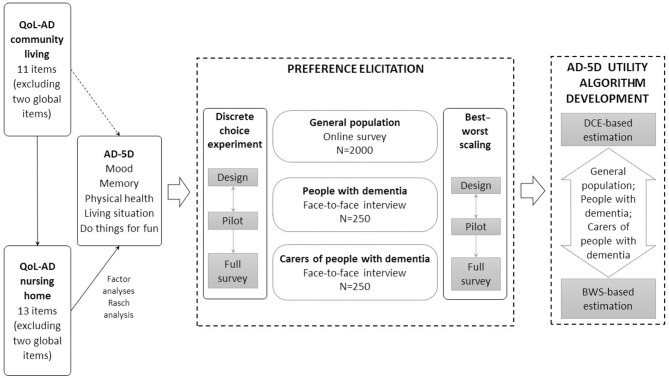

The purpose of this study is to generate a preference-based scoring algorithm for the AD-5D, the health state classification system derived from the QOL-AD. This will be achieved by eliciting values for a selection of health states and conducting statistical modelling to develop an algorithm that derives utility values for all possible health states defined by the AD-5D descriptive system. This paper describes the process and methodology we will use to develop the utility values for the AD-5D (summarised in figure 1). When complete, this algorithm will enable data collected from any administration of the QOL-AD to be used in the economic evaluation of treatments and interventions for people diagnosed with dementia.

Figure 1.

Process and methodology of the AD-5D project. AD-5D, Alzheimer ‘ s Disease Five Dimensions; BWS, best–worst scaling; QOL-AD, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s disease.

Aims

This study has two main objectives:

To value health states from the AD-5D descriptive system with a representative sample of the general population and a sample of dementia dyads (a person with dementia and a primary carer) in Australia using discrete choice experiment with duration (DCETTO) and best–worst scaling (BWS) elicitation techniques.

To identify any potential differences in the utility values elicited from the general population and those from the dementia dyads and between the two elicitation methods of DCE and BWS.

Methods and analysis

Preference elicitation methods

The most commonly used preference elicitation methods for valuing health states include standard gamble (SG),12 29 30 time trade-off (TTO),2 31 32 DCE33–35 and BWS (a particular form of DCE).36–38 Historically, researchers have favoured the SG and TTO to value health states.20 However, these methods have been criticised on the grounds of task complexity,39 intensity of administration40 and potential contamination by risk attitudes and time preference.41 Consequently, methods such as DCE and BWS have gained significant popularity in health economics research because they use an ordinal ranking procedure, and therefore present a different cognitive challenge for respondents, avoiding the use of iterative procedures.42 43 They can also be administered in both face-to-face and online settings, while online survey methodology for SG and TTO arguably requires further development to guarantee reliable results.44 45

In this project, we will use DCE with survival duration (DCETTO) and BWS to elicit preferences for health states described by the AD-5D. A DCE presents individuals with a number of hypothetical health states (ie, choice sets), each containing a number of alternatives with different attributes between which individuals are asked to choose. While this form of DCE can provide information on the relative preference of one health state over others, its derived values are not anchored on the 0–1 utility scale,46 thus cannot be used directly for QALY calculation. The DCETTO method was developed to directly anchor relative preferences to the utility scale through the inclusion of a survival/duration attribute, while fitting within the constraints of random utility theory.46 In our DCETTO, choice sets presenting levels of the five dimensions of the AD-5D (memory, mood, physical health, living situation and do things for fun) and one survival duration attribute will be presented. Each dimension has four ordinal severity levels (‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘fair’ and ‘poor’). A duration attribute with four levels (1, 4, 7 and 10 years) will be included to investigate individuals’ preferences with respect to survival durations.

BWS is a stated-preference method that presents respondents with a series of hypothetical health states and asks them to identify each state’s best and worst attribute, hence offering the ability to compare attributes and associated levels within a single health state. Compared with a DCETTO, BWS is less cognitively complex and may therefore be more appropriate for vulnerable groups such as older people or people with limited cognitive function.47–49 In this project, we will use a profile case BWS,50 in each of the tasks, respondents will be asked to pick the best and worst attribute of a health state.38

Experimental design and construction of choice sets

Discrete choice experiment tasks

The experimental design needs to determine both the total number of health states to be included in the valuation study and the combinations of health states to be valued by each respondent. The combination of attributes (five AD-5D dimensions and one duration) and levels (four levels for each attribute) results in the full factorial of 4096 possible health state profiles and over 16 million possible pairwise combinations (4096×4095). For practical purposes, a subset of these will be selected from a candidate set to reduce the number of health states used in the experiment while maximising the efficiency of the design.

A design maximised for the multinomial logit (MNL) model based on D-efficiency criteria will be used to generate 200 pairwise choice sets using the design software NGene.51 We will generate a design that can estimate the health state dimension and duration level main effects, as well as interactions between the health state dimensions and duration required to anchor DCETTO data on the full health—dead scale. Previous research suggests that participants can efficiently handle 10 choice sets at a time if they do not have any cognitive impairment,47 while five to six choice sets are optimal for people with mild cognitive impairment.52 Consequently, the full design will be divided into 20 blocks (versions) of the survey with 10 choice sets per block for the general population survey and 40 blocks with five choice sets per block for the dementia dyads interview. The blocking design will ensure balance among attribute levels.53 The construction of choice sets will also allow both the main effects (the effect of each attribute) and interaction effects between the attribute and duration to be determined. An example of a DCETTO choice task is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Presentation of a DCE task

| Health description A | Health description B | |

| You have poor physical health | You have excellent physical health | |

| You have good mood | You have fair mood | |

| You have fair memory | You have fair memory | |

| You have good living situation | You have fair living situation | |

| You have good ability to do things for fun | You have good ability to do things for fun | |

| You live in this state for 4 years and then you die. | You live in this state for 7 years and then you die. | |

| Which scenario do you think is better? | ☒ | ☐ |

DCE, discrete choice experiment.

Best–worst scaling task

In each BWS choice set, only one health state based on the AD-5D is included. An orthogonal array will generate health state profiles for use in the BWS to minimise multicollinearity among different levels of the attributes, thus optimising the design. A total of 16 health states will be generated. The full design is separated into four blocks so that each respondent will be presented with four choice sets for valuation. The blocks will be used for both the general population survey and dementia dyad interviews. An example of a BWS choice task is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Presentation of a BWS task

| Best | Health description | Worst |

| O | You have good memory | O |

| O | You have poor mood | O |

| O | You have excellent physical health | O |

| O | You have fair living situation | O |

| O | You have fair ability to do things for fun | O |

BWS, best–worst scaling.

Survey format

Debate exists as to whose preferences are important when assessing healthcare.54 A prevailing view is that the general public funds services in a public health system and therefore their preferences should be taken into account when assessing programme for funding. On the contrary, other views are that only people who have experienced the condition could provide a reasonable perspective to inform preferences for that condition. Patient and public preferences can vary, with the public often framing aspects such as mobility and leisure constraints more negatively than people experiencing a condition where these aspects are impacted.55 In our project, the survey will be administered to both the general population and to dementia dyads so that either value is available to inform economic evaluations.

General public

A web-based survey that contains three modules will be administered to a sample of the Australian general population in October to December 2017. In the first module, respondents will be given an introduction to the study and required to provide consent to continue the survey. Demographic data will be collected (eg, gender, age, education, marital status and employment) that can be used to determine the representativeness of the sample compared with the Australian population. In addition, respondents will be required to self-complete two quality of life questionnaires, the EQ-5D-5L and the QOL-AD (community living version) before commencing the main tasks.

The second and third modules will contain the DCETTO tasks (10 choice sets) and the BWS tasks (four choice sets). The order of these modules will be randomly assigned to eliminate order effects bias in the responses: half of the general population sample will complete DCETTO first, the other half BWS first. At the start of each module, respondents will be given information and instructions on how to complete the DCETTO or BWS tasks and shown a sample task. To assess internal reliability and consistency of responses, 1 repeated choice set (from each of the DCETTO or BWS blocks) and 1 dominant choice set will be included, creating 12 DCE and 6 BWS choice sets to be presented to each general population participant.

At the end of the DCETTO and BWS modules, respondents will be asked to rate their difficulty completing each task. At the end of the survey, respondents will be asked to compare the difficulty levels between DCETTO and BWS tasks and provide information on their prior experience of dementia.

Dementia dyads (one person with dementia and a primary carer)

A survey with three modules will be administered to dementia dyads during a face-to-face interview. The first module will collect basic demographic data (eg, gender, age, education, marital status and employment), experience with dementia such as type of dementia, time since formal diagnosis and quality of life (using the EQ-5D-5L and the QOL-AD). The person with dementia will complete a General Practitioner-Cognition Test (GP-Cog) task as a quick reliable screen of cognitive function,56 while the carer will be asked questions about their care experience, time commitment and her/his own health. The second and third modules consist of DCETTO and BWS tasks. To reduce the cognitive burden for people with dementia, fewer choice sets (five DCETTO choice sets and four BWS choice sets) will be administered during interviews.52 A standard script will be created as part of the interview protocol to explain the DCETTO and BWS tasks to dementia dyads in plain language, with standard prompts if required.

Sample size and recruitment

Two different samples are required to achieve the study objectives: the general population and the dementia dyad. The current theory of sampling determines that sample sizes are based on the characteristics of the study design, such as the number of attributes, the size of the population and the statistical power that is required of the model derived. Based on the suggestions in the literature and previous studies using DCETTO and BWS methodology,40 47 we have set our recruitment target at 2000 members of the general population and 250 dementia dyads (250 people with dementia and 250 carers).

Quotas will be set for age, gender and geographic area during recruitment for the online survey to ensure the sample is representative of the Australian population. Survey respondents will be sourced from an existing Australian online panel, administered by PureProfile. This panel is drawn from volunteers (aged 18 and above and able to give consent) in the general population who are paid a small amount by the panel administrators for completion of the survey. The advantage of this approach is that a population can be drawn from the total available chosen based on prespecified criteria such as age and gender, thereby ensuring that a broadly representative population sample is obtained. Each respondent will use a web link to access the survey, so is able to self-complete at their convenience.

The recruitment process is guided by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council National Statement on Ethics Chapter 4.5.57 The statement articulates the right of people with a cognitive impairment to participate in research and outlines the considerations that need to be taken in this vulnerable population to ensure risks and burdens are justified. A sample of dementia dyads will be recruited from Queensland, New South Wales and South Australia from October 2017 to September 2018. A comprehensive recruitment approach will be undertaken by contacting eligible participants through aged care providers, residential aged care facilities and community centres in both metropolitan and regional areas. Purposeful sampling will be used with quotas set (eg, residential and community dwelling, gender, age) to ensure the generalisability of the findings. Recruitment follows a two-step process. First, the primary caregiver is phoned by a member of the research team after registration. A brief screening using set questions written for the study is used to assess suitability for inclusion into the study. The process of participation is explained and the caregiver is asked whether this is something that the person with dementia (PWD) would be capable of and comfortable with. If during the telephone conversation it is clear that the PWD has severe dementia or is unable to respond to questions or is likely to be distressed by an interview from an unfamiliar person, the person is excluded from participation. If preliminary eligibility is determined, a face-to-face interview is booked and information about the study is posted to the participants.

Second, the research assistant checks on arrival for interview that the participant information sheet has been received and goes through this with the person and the carer, reminding them that participation is voluntary and they can withdraw or stop at any time. Consent to participate is then obtained (the PWD’s consent is witnessed by the primary caregiver). Interviewers will be people with experience in working with PWD and will have had additional training to be alert for signs of distress and modify or discontinue the interview as appropriate.

Pilot study

Pilot studies will be conducted with a subset of 200 (of 2000) from the general population sample and 25 (of 250) dementia dyads. The pilot aims to ascertain comprehension and understanding of the choice set tasks, attributes and their levels as well as the functioning of the survey instrument. The pilot will highlight any procedural issues for the experimental design of the survey and allow revisions if required. The average time taken during the online survey pilot will be used to set a minimum time for respondents to complete the main survey. Data from the pilot will be analysed to confirm the face validity of the survey instrument.

A think-aloud technique will be used in the pilot interviews with the dementia dyads to gauge participant understanding of the tasks and provide insight into the factors underlying the preferences of participants.58 By using the ‘think-aloud’ approach during the pilot, we are asking respondents to explain their thought process for making choices. If they repeatedly indicate they do not understand, or if the interviewer (who has experience working with PWD) deems they do not understand, transcripts and recordings of the interviews will be used by the research team, combined with GP-Cog scores, to review the recruitment and interviewing process for the remaining dyads.

Analytical plan

We will use an MNL (conditional) framework as outlined by McFadden59 to analyse both DCETTO and BWS responses. For both DCETTO and BWS, random effect utility functions will be estimated following the Random Utility Theory’s argument that the utility value that an individual attaches to an attribute in a choice scenario can be summarised by an explainable (fixed) component and an unexplainable (random) component.

The specific utility function for the DCETTO responses will be modelled using the approach developed and described by Bansback et al46 due to its additional time duration attribute. The BWS-based utility values will be estimated using a two-stage approach. In stage 1, the coefficients of a random effect utility function will be estimated, from which the BWS values will be generated. These values will be anchored onto the 1–0 full health dead scale (required to generate QALYs) in stage 2 by mapping the modelled values from a small selection of health states used for AD-5D (ranging from mild to severe impairment) generated from the DCETTO study to the ordinal best–worst estimates to translate the best–worst estimates. While this represents a new technique in this field, the process is equivalent to mapping from BWS to utility values using TTO47 or mapping from DCE to TTO.42

Ethics and dissemination

A steering committee consisting of researchers, consumers and aged care industry representatives will coordinate the project and oversee any concerns arising from the conduct of the research. This committee will meet monthly for the duration of the project.

This project will develop utility value sets for a new dementia-specific economic analysis tool, the AD-5D. This will be the first dementia-specific preference-based measure with an Australian value set. Once developed, the AD-5D utility algorithms can be used to generate utility weights from any completion of the QOL-AD instrument. The weights can be used to calculate QALYs for the economic evaluation of treatments and interventions targeting people with dementia. This algorithm is applicable not only to current and future clinical trials and intervention studies but also for previously collected data using the QOL-AD, from which the AD-5D was derived.

Dissemination will occur through academic publications and conference presentations. Algorithms developed in the project will be available online. As well, the authors will record an online video demonstrating the use of the algorithms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions to the design of this study from our consumer representatives from the NHMRC Cognitive and Related Function Decline Centre, Tara Quirke and Elaine Todd.

Footnotes

Contributors: TAC, K-HN, JR, BM, DR conceived the study; TAC, K-HN, JR, BM, DR, SK, MC, SEK and WM contributed to the design of the study; TAC, K-HN, AW and LL wrote the manuscript. All authors read, contributed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by funding provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Centre on Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People (grant number GNT9100000).

Disclaimer: The contents of the published materials are solely the responsibility of the Administering Institution, Griffith University and the individual authors identified, and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC or any other funding bodies or the funding partners.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study has ethical approval from Griffith University HREC (number 2016/626).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brazier J. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulhern B, Rowen D, Brazier J, et al. . Development of DEMQOL-U and DEMQOL-PROXY-U: generation of preference-based indices from DEMQOL and DEMQOL-PROXY for use in economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1–140. 10.3310/hta17050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laakkonen ML, Kautiainen H, Hölttä E, et al. . Effects of self-management groups for people with dementia and their spouses--randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:752–60. 10.1111/jgs.14055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karttunen K, Karppi P, Hiltunen A, et al. . Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients with very mild and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:473–82. 10.1002/gps.2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sintonen H. An approach to measuring and valuing health states. Soc Sci Med Med Econ 1981;15:55–65. 10.1016/0160-7995(81)90019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 1999;8:209–24. 10.1023/A:1008815005736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikmat AW, Hawthorne G, Al-Mashoor SH. The comparison of quality of life among people with mild dementia in nursing home and home care:: a preliminary report. Dementia 2015;14:114–25. 10.1177/1471301213494509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wlodarczyk JH, Brodaty H, Hawthorne G. The relationship between quality of life, mini-mental state examination, and the instrumental activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2004;39:25–33. 10.1016/j.archger.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wimo A, Mattson B, Krakau I, et al. . Cost-utility analysis of group living in dementia care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1995;11:49–65. 10.1017/S0266462300005250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerner DN, Patterson TL, Grant I, et al. . Validity of the Quality of Well-being Scale for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Aging Health 1998;10:44–61. 10.1177/089826439801000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan RM, Bush JW, Berry CC. Health status: types of validity and the index of well-being. Health Serv Res 1976;11:478–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, et al. . The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med 2001;33:375–84. 10.3109/07853890109002092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittmann N, Trakas K, Risebrough N, et al. . Utility scores for chronic conditions in a community-dwelling population. Pharmacoeconomics 1999;15:369–76. 10.2165/00019053-199915040-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann PJ, Kuntz KM, Leon J, et al. . Health utilities in Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study of patients and caregivers. Med Care 1999;37:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orgeta V, Edwards RT, Hounsome B, et al. . The use of the EQ-5D as a measure of health-related quality of life in people with dementia and their carers. Qual Life Res 2015;24:315–24. 10.1007/s11136-014-0770-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aguirre E, Kang S, Hoare Z, et al. . How does the EQ-5D perform when measuring quality of life in dementia against two other dementia-specific outcome measures? Qual Life Res 2016;25:45–9. 10.1007/s11136-015-1065-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulhern B, Smith SC, Rowen D, et al. . Improving the measurement of QALYs in dementia: developing patient- and carer-reported health state classification systems using Rasch analysis. Value Health 2012;15:323–33. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowen D, Mulhern B, Banerjee S, et al. . Estimating preference-based single index measures for dementia using DEMQOL and DEMQOL-Proxy. Value Health 2012;15:346–56. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drummond M, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. . Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hounsome N, Orrell M, Edwards RT. EQ-5D as a quality of life measure in people with dementia and their carers: evidence and key issues. Value Health 2011;14:390–9. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann PJ. Health utilities in Alzheimer’s disease and implications for cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:537–41. 10.2165/00019053-200523060-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arons AM, Schölzel-Dorenbos CJ, Olde Rikkert MG, et al. . A simple and practical index to measure dementia-related quality of life. Value Health 2016;19:60–5. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowen D, Mulhern B, Banerjee S, et al. . Comparison of general population, patient, and carer utility values for dementia health states. Med Decis Making 2015;35:68–80. 10.1177/0272989X14557178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen KH, Mulhern B, Kularatna S, et al. . Developing a dementia-specific health state classification system for a new preference-based instrument AD-5D. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:21 10.1186/s12955-017-0585-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edelman P, Fulton BR, Kuhn D, et al. . A comparison of three methods of measuring dementia-specific quality of life: perspectives of residents, staff, and observers. Gerontologist 2005;45:27–36. 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. . Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging 1999;5:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods R, et al. . A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging Ment Health 2008;12:14–29. 10.1080/13607860801919850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Neumann J. Theory of games and economic behavior. New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002;21:271–92. 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torrance GW, Thomas WH, Sackett DL. A utility maximization model for evaluation of health care programs. Health Serv Res 1972;7:118–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, et al. . The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ 1996;5:141–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SH, Ahn J, Ock M, et al. . The EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Korea. Qual Life Res 2016;25:1845–52. 10.1007/s11136-015-1205-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratcliffe J, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, et al. . Using DCE and ranking data to estimate cardinal values for health states for deriving a preference-based single index from the sexual quality of life questionnaire. Health Econ 2009;18:1261–76. 10.1002/hec.1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Propper C. Contingent valuation of time spent on NHS waiting lists. Econ J 1990;100:193–9. 10.2307/2234196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coast J, Flynn TN, Natarajan L, et al. . Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:874–82. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratcliffe J, Huynh E, Chen G, et al. . Valuing the child health utility 9D: using profile case best worst scaling methods to develop a new adolescent specific scoring algorithm. Soc Sci Med 2016;157:48–59. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louviere JJ, Woodworth GG. Best-worst scaling: a model for the largest difference judgments: University of Alta, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keeney RL, von Winterfeldt D. A prescriptive risk framework for individual health and safety decisions. Risk Anal 1991;11:523–33. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1991.tb00638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali S, Ronaldson S. Ordinal preference elicitation methods in health economics and health services research: using discrete choice experiments and ranking methods. Br Med Bull 2012;103:21–44. 10.1093/bmb/lds020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bleichrodt H. A new explanation for the difference between time trade-off utilities and standard gamble utilities. Health Econ 2002;11:447–56. 10.1002/hec.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowen D, Brazier J, Van Hout B. A comparison of methods for converting DCE values onto the full health-dead QALY scale. Med Decis Making 2015;35:328–40. 10.1177/0272989X14559542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson A, Spencer A, Moffatt P. A framework for estimating health state utility values within a discrete choice experiment: modeling risky choices. Med Decis Making 2015;35:341–50. 10.1177/0272989X14554715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oppe M, Devlin NJ, van Hout B, et al. . A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health 2014;17:445–53. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norman R, King MT, Clarke D, et al. . Does mode of administration matter? Comparison of online and face-to-face administration of a time trade-off task. Qual Life Res 2010;19:499–508. 10.1007/s11136-010-9609-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, et al. . Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate health state utility values. J Health Econ 2012;31:306–18. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Netten A, Burge P, Malley J, et al. . Outcomes of social care for adults: developing a preference-weighted measure. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:1–166. 10.3310/hta16160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flynn TN. Valuing citizen and patient preferences in health: recent developments in three types of best-worst scaling. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2010;10:259–67. 10.1586/erp.10.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, et al. . Best– worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ 2007;26:171–89. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flynn T, Marley A. Best-worst scaling: theory and methods. Worcester, UK: Edward Elgar, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Choice Metrics. Ngene User Manual Reference Guide. version 1.1. 2 2014.

- 52.Milte R, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, et al. . Cognitive overload? An exploration of the potential impact of cognitive functioning in discrete choice experiments with older people in health care. Value Health 2014;17:655–9. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, et al. . Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ispor conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health 2013;16:3–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stamuli E. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: who should value health? Br Med Bull 2011;97:197–210. 10.1093/bmb/ldr001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peeters Y, Vliet Vlieland TP, Stiggelbout AM, et al. . Focusing illusion, adaptation and EQ-5D health state descriptions: the difference between patients and public. Health Expect 2012;15:367–78. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00667.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brodaty H, Kemp NM, Low LF. Characteristics of the GPCOG, a screening tool for cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:870–4. 10.1002/gps.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. National Health and Medical Research Council. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007): National Health and Medical Research Council, 2011. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research (accessed 10 Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitty JA, Walker R, Golenko X, et al. . A think aloud study comparing the validity and acceptability of discrete choice and best worst scaling methods. PLoS One 2014;9:e90635 10.1371/journal.pone.0090635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Berkeley, California: University of California, 1973. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.