Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between bone mineral density (BMD) and hearing impairment using a nationally demonstrative sample of Korean female adults.

Study design

Cross-sectional study of a national health survey.

Methods

Data from the 2009–2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES) with 19 491 participants were analysed, and 8773 of these participants were enrolled in this study. BMD was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Auditory functioning was evaluated by pure-tone audiometric testing according to established KNHANES protocols. We deliberated auditory impairment as pure-tone averages at frequencies of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 kHz at a threshold of ≥40 decibels hearing level in the auricle with better hearing status.

Results

Among women aged 19 years and older, prevalences of bilateral hearing impairment in premenopausal and postmenopausal women were 0.1%±0.1% and 11.5%±1.1% (mean±SE), respectively. Hearing impairment was meaningfully associated with low BMD in postmenopausal women. Logistic regression models indicated that lower BMDs of the total femur (OR=0.779; 95% CI 0.641 to 0.946, P=0.0118) and femur neck (OR=0.746; 95% CI 0.576 to 0.966, P=0.0265) were significantly associated with hearing impairment among postmenopausal women.

Conclusions

Postmenopausal Korean women with low BMD of the total femur and femoral neck showed an increased risk for developing hearing impairment. Further epidemiological and investigational studies are needed to elucidate this association.

Keywords: hearing impairment, bone mineral density, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used a nationally, demonstrative, cross-sectional, civilian, non-institutionalised sample of Korean adults.

We evaluated the relationship between bone mineral density (BMD) and hearing level including various social, economic, behavioural and health variables using a population-based database.

We were unable to analyse temporal association between hearing impairment and BMD, which may make our results biased.

Introduction

Osteoporosis has become a main healthcare problem around the world.1 The prevalence of osteoporosis at the total hip or hip/spine was found to range from 9% to 38% in women and from 1% to 8% in men after analysing data from nine industrialised nations in North America, Europe, Japan and Australia.2 It has been stated that crucial demographic alterations might occur in Asia.3 The prevalence and incidence of osteoporosis are expected to increase in an ageing society.4 Osteoporosis is considered when there is worsening of bone microarchitecture and reduction in bone mineral density (BMD).5 Decreased BMD causes demineralisation of the bone system. Deterioration of the petrous temporal bone, which encases the cochlear capsule and internal auditory canal, might be associated with impaired hearing function.5–8 Osteoporosis is characteristically accepted as an important healthcare concern in women. However, it is now progressively regarded as a significant healthcare issue in men as well.

Adult-onset hearing impairment is another important public concern of disability among adults in high-income nations.9 The total prevalence of audiometric hearing loss among persons with bilateral hearing loss aged 12 years and older in the USA was 12.7% (30.0 million) between 2001 and 2008. This increased to 20.3% (48.1 million) when individuals with unilateral hearing loss were included.10 Hearing impairment can isolate individuals from their social environment, impair psychosocial functioning, impair cognitive skills, increase individual emotional stress, and have negative health effects at the individual and family levels.11 Moreover, it has been recently described that hearing impairment is associated with a menace of depression among adults, particularly women.12

Several studies have evaluated the relationship between BMD and hearing sensitivity. Clark et al have reported that 369 white women aged 60–85 years with femoral neck skeletal mass values below the mean value of 0.696 g/cm2 have a 1.9-fold greater odds of having a hearing loss.5 In contrast, Helzner et al have shown no association between hearing and any of bone measurements in white or black women.13 There are discrepancies and limitations in previous studies on the associations between BMD and hearing impairment, including differences in race, study design and measurements of hearing impairment.14 Thus, the objective of this study was to assess the relationship between BMD and hearing impairment in a representative sample of Korean adult populations. Understanding and identifying the association between BMD and hearing impairment in an extensive research could provide important information for patient management and reduction of social burden for these conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report of a nationwide study on hearing impairment diagnosed by otolaryngology doctors or the relationship between BMD and hearing impairment in Asian women. Thus, we investigated the association between BMD and hearing impairment in a large representative population sample from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES).

Methods

Study population

This study was based on data collected from the 2009–2010 KNHANES study conducted by the Division of Chronic Disease Surveillance under the supervision of Korea’s Centers for Disease Control & Prevention since 1998. The KNHANES is a nationwide survey designed to accurately assess health and nutritional status at the national level. A field survey team including an otolaryngologist, an ophthalmologist and nurses travels with a mobile examination unit, and perform interviews and physical examinations. The survey consisted of a health interview, a nutritional survey and a health examination survey. The survey collected data via household interviews and by direct standardised physical examinations conducted in especially equipped mobile examination centres. The KNHANES methodology has been described in detail previously.15 16 Further details are listed in ‘The 5th KNHANES Sample Design’ and reports, made accessible on the KNHANES website (https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.do). The KNHANES annual reports, user manuals and instructions, and raw data are available on request.

This study was a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of a nationwide health survey. We hypothesised that auditory impairment was positively correlated with low BMD in Korean population before analysing the data. In 2009–2010, there were 19 491 KNHANES participants. Of these, 10 718 were excluded from the analysis due to at least one of the following reasons: younger than 19 years; did not undergo ontological, BMD or 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) test; or with missing data on the lifestyle questionnaire. The final sample included 8773 adults aged 19 years, including 3885 men, 2622 premenopausal women and 2266 postmenopausal women. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the survey.

BMD and laboratory measurements

Participants wore light clothes without shoes or jewellery, which could interfere with BMD measurements. BMD was checked by trained technicians at mobile examination centres. BMD values of the lumbar spine (L1–L4), femoral neck and total femur were obtained using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and a Discovery fan-beam densitometer (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA) with Hologic Discovery software (V.3.1). To guarantee DXA quality control, daily programmed calibration was done according to the manufacturer’s directions to keep a precision standard of 1.5% for total hip measurements.

Standing height was calculated with the subject looking forward, barefoot, feet together, and arms at sides with heels, buttocks and upper back in contact with the wall. Height was measured in centimetres to one decimal point using a calibrated stadiometer (seca 225 stadiometer, seca, Hamburg, Germany). Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the level of the midpoint between the iliac crest and the costal margin at the end of a normal expiration to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight was measured using a mobile scale (GL-6000–20; CAS Korea, Seoul, Korea) in kilograms to one decimal point. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Blood samples for biochemical analyses and measurement of serum 25(OH)D were collected from all subjects, refrigerated instantly, carried to Principal Analysis Foundation (Seoul, Korea) and scrutinised within 24 hours.

Audiometric measurements

Pure-tone audiometric test was done with an SA 203 audiometer (Entomed; Malmö, Sweden). Pure-tone audiometry is a behavioural assessment used to calculate hearing sensitivity. ‘Audiometric’ means ‘measuring the hearing level’. Examination was done in a soundproof booth inside a transportable bus set aside for the KNHANES. Otolaryngologists skilled to work on the audiometer provided directions to subjects regarding the automated hearing test. Records were attained. All audiometric analyses were performed under the supervision of an otolaryngologist. Solely thresholds of air conduction were investigated. Air conduction assessed the whole ear system—outer, middle and inner ear. Threshold meant the lowest decibel hearing level (dBHL) at which responses occurred in at least one half of a series of ascending trials. The minimum number of responses needed to determine the threshold of hearing was two responses out of three presentations at a single level. Over-ear headphones were used in the soundproof booth. Supra-auricular was defined as ‘situated above the ear coverts’. Automated analysis was platformed according to a modified Hughson-Westlake procedure using a single pure tone of 1–2 s. The lowest level at which the participant answered to 50% of the pure tone was established as the threshold. Test–retest reliability and validity of the automated hearing examination relating to air-conducted pure-tone provocations were effective and equivalent to those attained in the manual pure-tone acoustic assessment.17 18 Subjects answered by pressing a button when they caught a tone. Outcomes were documented spontaneously. Frequency ranges tested were 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 6.0 kHz. We described hearing impairment as pure-tone averages of frequencies at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 kHz at a threshold of ≥40 dBHL in the ear with better hearing.19

Participants were asked about their experience of tinnitus: ‘Within the past year, have you ever heard a sound (buzzing, hissing, ringing, humming, roaring, machinery noise) come from your ear?’ Investigators were instructed to record ‘yes’ if an applicant stated perceiving an odd or unusual sound at any time in the past year. Subjects who responded certainly to this question were then asked about the annoyance in their lives using the following question: ‘How annoying is this sound in daily life?’ (not annoying/annoying/severely annoying and causes sleep problems). Participants were deliberated to have tinnitus if the severity of tinnitus was annoying or severely annoying.

Lifestyle habits

Data on medical histories and lifestyle habits were collected using self-report questionnaires. Participants were categorised into three groups according to smoking history: current smoker, ex-smoker and non-smoker. Subjects who drank more than 30 g of ethanol/day were designated as drinkers. Regular exercise was defined as strenuous physical activity performed for at least 20 min at a time at least three times per week. Subjects stated their levels of stress as none, mild, moderate or severe.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 to reveal the complex sampling design and sampling weights of the KNHANES, and to provide nationwide demonstrative prevalence assessments. The prevalence and 95% CIs for BMD were calculated. On univariate analysis, Rao-Scott χ2 test (using PROC SURVEYFREQ in SAS) and logistic regression analysis (using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC in SAS) were used to examine the relationship between hearing impairment and risk factors in a complex sampling design. The characteristics of the subjects were expressed as means and SEs for continuous variables, or as percentages for categorical variables. To examine the association between hearing level and BMD, participants were divided into quartiles based on the level of BMD (Q1–Q4). Simple and multiple linear regression analyses were performed to investigate the relationship between hearing impairment and BMD.

We first adjusted for age and BMI (model 1). We then adjusted for variables in model 1, as well as smoking status, ethanol intake, exercise, education and income (model 2). Model 3 was adjusted for variables in model 2, as well as vitamin D, stress and tinnitus. P values were two-tailed. Statistical significance was considered at P<0.05.

Results

Of 4888 female participants aged ≥19 years, 2622 and 2266 were premenopausal and postmenopausal, respectively. Table 1 shows the baseline features of men, premenopausal women and postmenopausal women. The mean ages of men, premenopausal women and postmenopausal women were 43.9±0.3, 35.3±0.2 and 62.7±0.3 years, respectively. The prevalence of bilateral hearing impairment in postmenopausal women was 11.5%±1.1% (mean±SE). Compared with men and premenopausal women, there were fewer postmenopausal women who were ethanol drinkers but more women with low income. The mean values of BMI, WC and vitamin D level were lower in premenopausal women than those in postmenopausal women. The BMDs of the lumbar spine, total femur and femoral neck were lower in postmenopausal women than those in men or premenopausal women. The characteristics of the subjects according to bilateral hearing impairment are shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects

| Bilateral hearing impairment | |||

| No (n=8214) |

Yes (n=559) |

P value | |

| Age (years) | 43.6±0.3 | 69.9±0.6 | <0.0001* |

| Average hearing level (dB) | 10.5±0.2 | 57.1±1.5 | <0.0001* |

| Smoking: current smoker (%) | 26.3±1.2 | 19.5±4.5 | 0.0086* |

| Drinking: heavy drinker (%) | 10.3±0.9 | 6.7±2.6 | 0.0311* |

| Routine exercise (%) | 24.9±1.4 | 18.9±3.8 | 0.0052* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7±0.0 | 23.8±0.2 | 0.3586 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 80.7±0.2 | 83.7±0.5 | <0.0001* |

| Education: ≥ high school (%) | 73.0±1.8 | 14.6±3.8 | <0.0001* |

| Residential area: urban (%) | 81.1±4.5 | 67.7±8.6 | <0.0001* |

| Income: lower quartile (%) | 14.9±1.5 | 50.0±4.8 | <0.0001* |

| Stress: moderate to severe (%) | 30.4±1.3 | 25.8±5.1 | 0.0937 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | 18.5±0.2 | 20.2±0.6 | 0.0013* |

| BMD of lumbar spine (g/cm2) | 0.947± 0.002 | 0.841±0.008 | <0.0001* |

| BMD of total femur (g/cm2) | 0.929± 0.002 | 0.799±0.008 | <0.0001* |

| BMD of femoral neck (g/cm2) | 0.778± 0.002 | 0.629±0.008 | <0.0001* |

*P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

BMD, bone mineral density.

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects according to bilateral hearing impairment

| Men (n=3885) |

Premenopausal women (n=2622) | Postmenopausal women (n=2266) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 43.9±0.3 | 35.3±0.2 | 62.7±0.3 | <0.0001* |

| Average hearing level (dB) | 19.1±0.4 | 12.3±0.4 | 30.6±0.8 | <0.0001* |

| Smoking: current smoker (%) | 45.4±1.0 | 7.1±0.7 | 4.6±0.6 | <0.0001* |

| Drinking: heavy drinker (%) | 18.2±0.8 | 2.6±0.4 | 0.9±0.2 | <0.0001* |

| Routine exercise (%) | 27.3±0.8 | 21.3±1.0 | 22.6±1.3 | <0.0001* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.1±0.1 | 22.6±0.1 | 24.3±0.1 | <0.0001* |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 84.0±0.2 | 74.8±0.3 | 82.3±0.3 | <0.0001* |

| Education: ≥ high school (%) | 77.0±0.9 | 89.7±0.7 | 20.7±1.3 | <0.0001* |

| Residential area: urban (%) | 80.1±2.3 | 85.8±2.0 | 73.2±2.9 | <0.0001* |

| Income: lower quartile (%) | 14.5±0.8 | 9.6±0.8 | 33.0±1.4 | <0.0001* |

| Stress: moderate to severe (%) | 27.4±0.9 | 35.2±1.1 | 29.8±1.3 | <0.0001* |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | 19.8±0.2 | 16.4±0.2 | 19.0±0.3 | <0.0001* |

| BMD of lumbar spine (g/cm2) | 0.971±0.003 | 0.977±0.003 | 0.807±0.004 | <0.0001* |

| BMD of total femur (g/cm2) | 0.986±0.003 | 0.905±0.003 | 0.782±0.003 | <0.0001* |

| BMD of femoral neck (g/cm2) | 0.829±0.003 | 0.765±0.003 | 0.626±0.003 | <0.0001* |

| Hearing loss (%) | 4.6±0.4 | 0.2±0.1 | 11.5±1.1 | <0.0001* |

*P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data are presented as mean±SE.

BMD, bone mineral density.

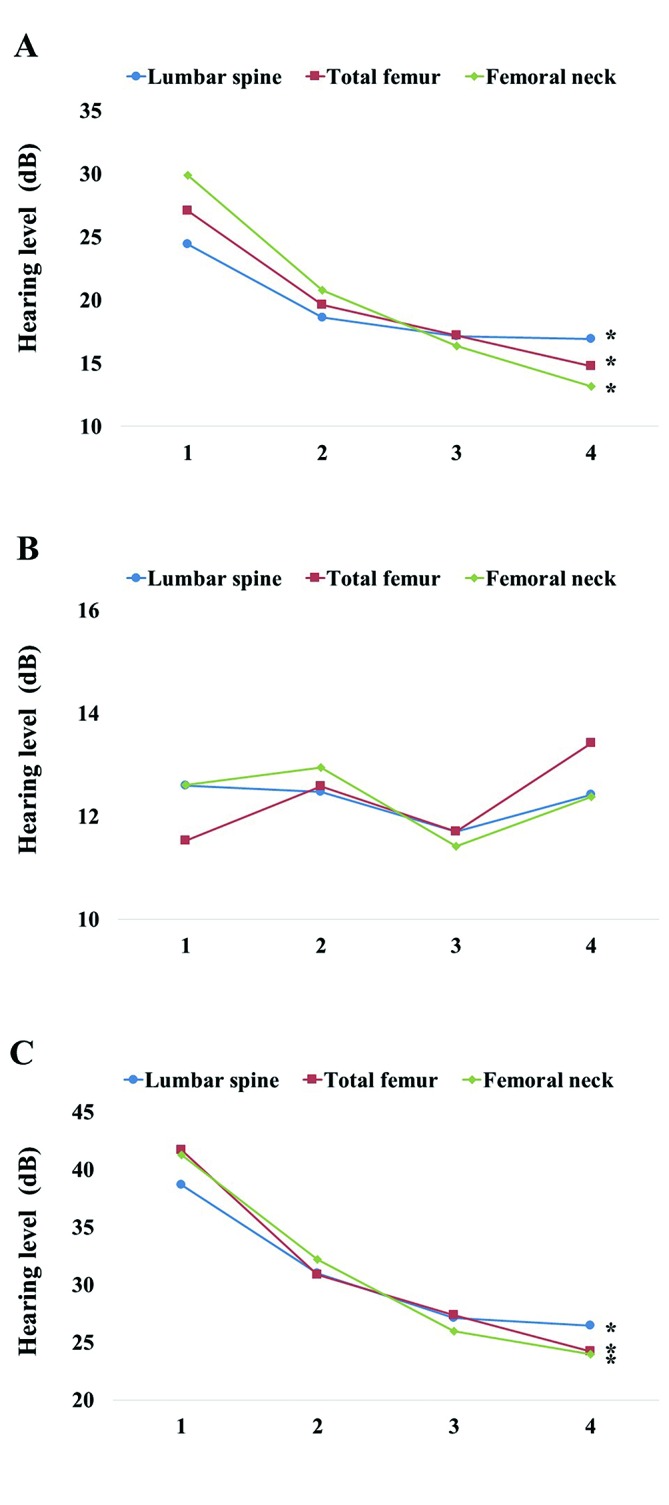

After categorising subjects into four groups based on the percentage of BMD (quartile 1, with the highest, to quartile 4, with the lowest), we performed analysis of covariance to investigate hearing level according to BMD quartile at various skeletal sites after adjusting for confounding variables such as age, BMI, smoking status, ethanol consumption, regular exercise, educational level, income, 25(OH)D, stress level and tinnitus. Lumbar skeleton, total femur skeleton and femoral neck BMD in postmenopausal women showed significantly decreased tendencies in hearing level as BMD decreased in quartiles (P<0.0001; figure 1). However, BMDs at the lumbar skeleton (P=0.570), total femur skeleton (P=0.358) or femur neck (P=0.268) of premenopausal women showed no statistically significant association with hearing level. Those of men showed no statistically significant association with hearing level either.

Figure 1.

Mean values of hearing level according to bone mineral density (BMD) for premenopausal women (A), postmenopausal women (B) and men (C). After categorising subjects into four groups based on BMD (quartile 1, with the highest, to quartile 4, with the lowest) in the lumbar spine, total femur and femur neck, we found a tendency towards significantly decreased hearing as a function of quartile decreases in BMD among postmenopausal women. *P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 3 demonstrates the association between hearing impairment and BMD using logistic regression models. In the final regression model for hearing impairment, BMDs of the total femur (OR=0.779; 95% CI 0.641 to 0.946) and femoral neck (OR=0.746; 95% CI 0.576 to 0.966) were significantly associated with hearing impairment in postmenopausal women after adjusting for age, BMI, smoking status, ethanol intake, regular exercise, educational level, income, vitamin D, stress level and tinnitus (model 3). BMD at the lumbar spine (OR=0.525; 95% CI 0.279 to 0.989) was also significantly associated with hearing impairment in premenopausal women. However, BMD at the total femur or femoral neck in men or premenopausal women did not show any significant correlation with hearing impairment. To ascertain the relations between hearing impairment and BMD at several skeletal sites, simple linear logistic regression analysis was performed after adjusting for age, BMI, smoking status, ethanol intake, regular exercise, educational level, income, 25(OH)D, stress level and tinnitus. There was no statistically significant association between hearing impairment and BMD at any parts of skeletal sites in men, and in premenopausal or postmenopausal women (table 4).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of adjusted ORs and 95% CIs to determine the effect of bone mineral density on hearing impairment

| Men | Premenopausal women | Postmenopausal women | |

| Lumbar spine | |||

| Model 1 | 0.999 (0.892 to 1.118) | 0.486 (0.276 to 0.856) | 0.921 (0.812 to 1.044) |

| Model 2 | 1.052 (0.939 to 1.178) | 0.528 (0.273 to 1.020) | 0.966 (0.849 to 1.098) |

| Model 3 | 1.058 (0.937 to 1.195) | 0.525 (0.279 to 0.989) | 0.960 (0.835 to 1.103) |

| Total femur | |||

| Model 1 | 0.948 (0.821 to 1.095) | 0.683 (0.323 to 1.444) | 0.804 (0.673 to 0.959) |

| Model 2 | 0.985 (0.851 to 1.140) | 0.756 (0.348 to 1.640) | 0.820 (0.686 to 0.981) |

| Model 3 | 1.009 (0.855 to 1.190) | 0.758 (0.338 to 1.703) | 0.779 (0.641 to 0.946) |

| Femoral neck | |||

| Model 1 | 0.874 (0.727 to 1.050) | 0.878 (0.412 to 1.868) | 0.760 (0.608 to 0.950) |

| Model 2 | 0.914 (0.761 to 1.099) | 0.970 (0.432 to 2.180) | 0.783 (0.623 to 0.984) |

| Model 3 | 0.919 (0.747 to 1.130) | 0.953 (0.400 to 2.272) | 0.746 (0.576 to 0.966) |

Model 1 is adjusted for age and body mass index.

Model 2 is adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, ethanol intake, regular exercise, educational level and income.

Model 3 is adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, ethanol intake, regular exercise, educational level, income, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, stress level and tinnitus.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of bone mineral density

| Men | Premenopausal women | Postmenopausal women | |||||||

| Beta | SE | P value | Beta | SE | P value | Beta | SE | P value | |

| Lumbar spine | |||||||||

| Model 1 | −0.2899 | 0.2570 | 0.2604 | −0.1820 | 0.1338 | 0.1753 | −0.0778 | 0.1560 | 0.6186 |

| Model 2 | −0.0194 | 0.2472 | 0.9375 | −0.1244 | 0.1320 | 0.3471 | 0.1261 | 0.1449 | 0.3847 |

| Model 3 | 0.0777 | 0.2517 | 0.7578 | −0.1400 | 0.1365 | 0.3063 | 0.1055 | 0.1482 | 0.4772 |

| Total femur | |||||||||

| Model 1 | −1.1271 | 0.3862 | 0.0038 | 0.0260 | 0.1426 | 0.8553 | −0.2160 | 0.1653 | 0.1924 |

| Model 2 | −1.0141 | 0.3913 | 0.0101 | 0.0034 | 0.1454 | 0.8118 | −0.0549 | 0.1586 | 0.7296 |

| Model 3 | −0.8842 | 0.3892 | 0.0240 | 0.0266 | 0.1511 | 0.8609 | −0.0038 | 0.1690 | 0.8201 |

| Femoral neck | |||||||||

| Model 1 | −0.8639 | 0.4739 | 0.0695 | 0.1211 | 0.1328 | 0.3625 | −0.0713 | 0.1646 | 0.6650 |

| Model 2 | −0.6742 | 0.4917 | 0.1716 | 0.1004 | 0.1335 | 0.4528 | 0.0031 | 0.1565 | 0.8409 |

| Model 3 | −0.5278 | 0.4737 | 0.2663 | 0.0847 | 0.1392 | 0.5433 | −0.0006 | 0.1648 | 0.9969 |

Model 1 is adjusted for age and body mass index.

Model 2 is adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, ethanol intake, regular exercise, educational level and income.

Model 3 is adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, ethanol intake, regular exercise, educational level, income, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, stress level and tinnitus.

Results are presented as an estimated beta with corresponding SE and P value.

Discussion

The main objective of this research was to examine the association between BMD and hearing impairment using a nationwide representative sample of South Korean population. Our findings indicated that low BMDs of the total femur skeleton and femur neck were associated with an increased risk for impairment of hearing function in postmenopausal women.

Some previous studies have reported that reduced BMD is closely associated with hearing impairment.5 13 The bone mass of the femoral neck is associated with hearing loss in a population of rural women aged 60–85 years.5 Another research has enrolled 2052 older adults aged 73–84 years using a randomised method.13 The population was composed of white men (32.2%), white women (30.8%), black men (15.1%) and black women (22.0%). Their results showed that the BMD of the total hip was not associated with hearing loss in white men, white women or black women. However, it was associated with hearing loss in black men.13 Unlike our results, this study only investigated the BMD of the total hip. Age range and race of the sample also differed from those of ours. However, their study did show that there were differences in hearing impairment by race and sex.

The mechanism of hearing impairment in postmenopausal women with lower BMD might involve demineralisation of cochlear capsule of the temporal bone, which could lead to loss of the delicate stereocilia of the cochlea.14 The cochlear capsule is situated in the petrous portion of the temporal bone. This portion is primarily composed of cancellous bone components.20 The demineralisation of the cochlear capsule has been related to auditory loss in subjects with skeletal diseases, such as Paget’s disease, otosclerosis and osteogenesis imperfecta.7 14 21 Deteriorated auditory function at a specific frequency has been associated with lower BMD within the cochlear capsule.22 Demineralisation of the petrous temporal bone affects the encasing compartment of the cochlear capsule. Spiral ligament hyalinisation might be affected by the toxic effects of the enzymes released from otospongiotic foci, thus leading to hearing impairment.21 Lower BMD of the petrous portion of the temporal bone can affect the dissipation of cochlear stereocilia. It could be a cause of hearing loss in subjects with sensorineural hearing loss.22 This phenomenon supports the occurrence of age-related sensorineural loss and the fact that the severity of cochlear hearing loss is influenced by the extent of cochlear demineralisation.5 23

Our study showed that differences related to menopause might contribute to the relationship between bone mass and hearing impairment. It has been reported that oestrogen can exert a positive effect on hearing among older women.24 Furthermore, oestradiol treatment might have a positive effect on ionic homeostasis of the inner ear and offer protection of activated intermediated filaments.25 Thus, oestrogen might contribute to differences in hearing impairment among women, such as those between premenopausal and postmenopausal women.26 27 Oestrogen may play an important role in the maintenance or repair of sensory epithelia of the inner ear. It may act as an auditory protectant.28–30

Screening for hearing impairment is important. Patients, clinicians, family and healthcare staff often do not identify hearing loss exactly in its initial period, and this condition might be undertreated.31 In addition, hearing impairment may favour the development of dementia and intellectual dysfunction in grown-ups aged 65 years and older.32 Hearing impairment is positively correlated with depression among US grown-ups, particularly among women and those younger than 70 years.12 Therefore, hearing screening tests based on risk factors are essential. Physicians should be aware of the likelihood of hearing damage in postmenopausal women.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not directly quantify the BMD of the cochlear capsule of the temporal bone. There were no data on any association between BMD in the petrous site of the temporal bone and that of the appendicular skeleton. However, previous research has indicated that osteoporosis can affect skull skeletons. Patients with hyperthyroid-related osteoporosis suffered from decreased skull bone density. Demineralisation of the petrous site of the temporal bone has been observed in patients with severe osteoporosis.33 34 It has been reported that high-resolution CT is useful in investigating the association between BMD of the petrous portion of the temporal bone and hearing loss.21 Under ideal conditions, BMD of the petrous portion of the temporal bone should be measured. However, there is no feasible or accurate method to measure BMD in large populations. Second, we were unable to evaluate the temporal relation between hearing impairment and BMD. Acceptable evaluation of the presence of hearing impairment is limited for extended periods. Therefore, we were unable to investigate hearing variabilities in these populations. The final limitation of this study was the absence of bone-conduction pure-tone testing. The audiometric assessment could not entirely exclude conductive hearing losses. Despite these limitations, no previous study has evaluated the association between hearing impairment and low BMD in a representative general female population in Asia. Additionally, these results might be reliable because the data used in this study were obtained from a government-sponsored survey of the national population of South Korea, qualified by DXA, validated by audiometry tests and verified by otolaryngologists.

Conclusion

Low BMDs in the total femur and femoral neck were associated with impaired hearing status in postmenopausal women. Future cohort studies with larger sample sizes and controls for possible confounders are needed to clarify the association between hearing impairment and BMD in postmenopausal women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the 150 medical residents of the otorhinolaryngology departments of 47 training hospitals in South Korea who are members of the Division of Chronic Disease Surveillance of Korea’s Centers for Disease Control & Prevention for their participation in this survey and for their dedicated work.

Footnotes

Contributors: S-SL wrote the first draft of the manuscript and took part in the data analyses. K-DH performed statistical analyses. Y-HJ designed the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant (HC16C2285) from the Korean Health Technology and Research and Development project funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea (IRB no HC14EISE0097; Bucheon, Korea).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The KNHANES methodology has been described in detail previously and further details are listed in ’The 5th KNHANES Sample Design' and reports, made accessible on the KNHANES website: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.do. The KNHANES annual reports, user manuals and instructions, and raw data are available on request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Prevention and management of osteoporosis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2003;921:1–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wade SW, Strader C, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. . Estimating prevalence of osteoporosis: examples from industrialized countries. Arch Osteoporos 2014;9:182 10.1007/s11657-014-0182-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 1997;7:407–13. 10.1007/PL00004148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cole ZA, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Osteoporosis epidemiology update. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2008;10:92–6. 10.1007/s11926-008-0017-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark K, Sowers MR, Wallace RB, et al. . Age-related hearing loss and bone mass in a population of rural women aged 60 to 85 years. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:8–14. 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00035-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petasnick JP. Tomography of the temporal bone in Paget’s disee. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1969;105:838–43. 10.2214/ajr.105.4.838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huizing EH, de Groot JA. Densitometry of the cochlear capsule and correlation between bone density loss and bone conduction hearing loss in otosclerosis. Acta Otolaryngol 1987;103:464–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chakeres DW, Weider DJ. Computed tomography of the ossicles. Neuroradiology 1985;27:99–107. 10.1007/BF00343778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2008. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/

- 10. Lin FR, Niparko JK, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1851–2. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hogan A, O’Loughlin K, Miller P, et al. . The health impact of a hearing disability on older people in Australia. J Aging Health 2009;21:1098–111. 10.1177/0898264309347821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li CM, Zhang X, Hoffman HJ, et al. . Hearing impairment associated with depression in US adults, national health and nutrition examination survey 2005-2010. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:293–302. 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Helzner EP, Cauley JA, Pratt SR, et al. . Race and sex differences in age-related hearing loss: the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:2119–27. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Helzner EP, Cauley JA, Pratt SR, et al. . Hearing sensitivity and bone mineral density in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1675–82. 10.1007/s00198-005-1902-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park SH, Lee KS, Park HY. Dietary carbohydrate intake is associated with cardiovascular disease risk in Korean: analysis of the third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES III). Int J Cardiol 2010;139:234–40. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park HA. The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey as a primary data source. Korean J Fam Med 2013;34:79 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swanepoel deW, Mngemane S, Molemong S, et al. . Hearing assessment-reliability, accuracy, and efficiency of automated audiometry. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:557–63. 10.1089/tmj.2009.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mahomed F, Swanepoel deW, Eikelboom RH, et al. . Validity of automated threshold audiometry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ear Hear 2013;34:745–52. 10.1097/01.aud.0000436255.53747.a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. Millions of people in the world have hearing loss that can be treated or prevented: 2013 update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swinnen FK, De Leenheer EM, Goemaere S, et al. . Association between bone mineral density and hearing loss in osteogenesis imperfecta. Laryngoscope 2012;122:401–8. 10.1002/lary.22408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Güneri EA, Ada E, Ceryan K, et al. . High-resolution computed tomographic evaluation of the cochlear capsule in otosclerosis: relationship between densitometry and sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1996;105:659–64. 10.1177/000348949610500813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swartz JD, Mandell DW, Berman SE, et al. . Cochlear otosclerosis (otospongiosis): CT analysis with audiometric correlation. Radiology 1985;155:147–50. 10.1148/radiology.155.1.3975393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mendy A, Vieira ER, Albatineh AN, et al. . Low bone mineral density is associated with balance and hearing impairments. Ann Epidemiol 2014;24:58–62. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frisina RD, Frisina DR. Physiological and neurobiological bases of age-related hearing loss: biotherapeutic implications. Am J Audiol 2013;22:299–302. 10.1044/1059-0889(2013/13-0003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Horner KC, Troadec JD, Dallaporta M, et al. . Effect of chronic estradiol administration on vimentin and GFAP immunohistochemistry within the inner ear. Neurobiol Dis 2009;35:201–8. 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gordon-Salant S. Hearing loss and aging: new research findings and clinical implications. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005;42:9–24. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.01.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pearson JD, Morrell CH, Gordon-Salant S, et al. . Gender differences in a longitudinal study of age-associated hearing loss. J Acoust Soc Am 1995;97:1196–205. 10.1121/1.412231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sajan SA, Warchol ME, Lovett M. Toward a systems biology of mouse inner ear organogenesis: gene expression pathways, patterns and network analysis. Genetics 2007;177:631–53. 10.1534/genetics.107.078584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCullar JS, Oesterle EC. Cellular targets of estrogen signaling in regeneration of inner ear sensory epithelia. Hear Res 2009;252:61–70. 10.1016/j.heares.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nolan LS, Maier H, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, et al. . Estrogen-related receptor gamma and hearing function: evidence of a role in humans and mice. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:e2071–9. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pacala JT, Yueh B. Hearing deficits in the older patient: “I didn’t notice anything”. JAMA 2012;307:1185–94. 10.1001/jama.2012.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gurgel RK, Ward PD, Schwartz S, et al. . Relationship of hearing loss and dementia: a prospective, population-based study. Otol Neurotol 2014;35:775–81. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meunier P, Bianchi G, Edouard C, et al. . Bony manifestations of thyrotoxicosis. Orthop Clin North Am 1972;3:745–74. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khan A, Lore JM. Osteoporosis relative to head and neck. J Med 1984;15:279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.