Abstract

Objectives

To determine the mediating effects of depression on health-related quality of life and fatigue in individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

Tertiary urban hospital.

Participants

One hundred and eight patients (54% women) with MS participated in this study.

Outcome measures

Demographic and clinical data (weight, height, medication and neurological impairment), fatigue (Fatigue Impact Scale), depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II) and health-related quality of life (Short-Form Health Survey 36) were collected.

Results

Fatigue was significantly associated with bodily pain, physical function, mental health and depression. Depression was associated with bodily pain and mental health. The path analysis found direct effects from physical function, bodily pain and depression to fatigue (all, P<0.01). The path model analysis revealed that depression exerted a mediator effect from bodily pain to fatigue (B=−0.04, P<0.01), and from mental health to fatigue (B=−0.16, P<0.01). The amount of fatigue explained by all predictors in the path model was 37%.

Conclusions

This study found that depression mediates the relationship between some health-related quality of life domains and fatigue in people with MS. Future longitudinal studies focusing on proper management of depressive symptoms in individuals with MS will help determine the clinical implications of these findings.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, fatigue, depression, quality of life

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of this study was the inclusion of a homogeneous sample of individuals with multiple sclerosis and the use of specific statistical analyses.

Since this was a cross-sectional study, the cause and effect relationships between the associated variables cannot be inferred. In addition, the sample was composed of patients recruited from urban hospitals, not from the general population.

The level of depression in our sample of individuals with multiple sclerosis was lower than expected. We do not know if the presence of higher symptoms of depression can lead to further associations or effects.

We used a general but not disease-specific questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life. It is possible that the use of a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire would lead to other potential associations.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating disease of the central nervous system and includes a variety of symptoms that interfere with daily activities, social and working life, disturb emotional well-being, and reduce quality of life. A worldwide annual incidence of 5.2 per 100 000 persons and a prevalence of 112 cases per 100 000 habitants have been reported.1 In Spain, the prevalence of MS has been found to be 125 cases per 100 000 habitants2; however, recent studies have observed an increased prevalence in the previous decade.3 4

Among all symptoms experienced by people with MS, fatigue is considered one of the most disabling.5 The prevalence of fatigue in MS ranges from 53% to 80%.6 Fatigue is a risk indicator for conversion from moderate-severe disability to relapsing-remitting MS.7 In fact, fatigue is influenced by several aspects such as psychological status, social relationship, personal beliefs, as well as personal interaction with the environment.8 Among all potential relationships, depression and health-related quality of life exhibit the greatest impact on fatigue in people with MS.9 10

Depression is the most prevalent comorbid condition reported by subjects with MS.11 12 It has been recently reported that the presence of depression is an important determinant of cognitive performance13 and quality of life14 in individuals with MS. In fact, the relationship between related fatigue and depression is bidirectional: fatigue can promote depression, but depression may also contribute to worsening self-perceived fatigue. However, the results from current literature are sometimes conflicting. Bakshi et al 15 observed that fatigue was associated with depression, but independent of disability. Similarly, a recent study found that both fatigue and sleep disturbances contribute to the development of depression.16 Other authors have investigated the role of depression on fatigue. Kroencke et al 17 found that depressed mood was a significant predictor of fatigue, accounting for approximately 23% of its variance. Nevertheless, others have reported that depression is not directly related to fatigue.18

Since depression and fatigue can be related by multiple interactions, additional studies including other variables such as health-related quality of life are needed. In fact, fatigue and depression can also influence self-perceived quality of life. Tanriverdi et al 19 observed that fatigue and depression strongly influence the quality of life of individuals with MS. Recent studies have reported that depression and fatigue, as well as related disability and physical comorbidities, are associated with health-related quality of life in people with MS.9 10 20 Future studies investigating the association between depression, health-related quality of life and fatigue in MS are necessary. In fact, a better understanding of the possible interaction between these multidimensional aspects associated with fatigue can potentially assist clinicians in determining better therapeutic programmes for individuals with MS. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to further determine the mediating effects of depression on the association between health-related quality of life and fatigue in individuals with MS. Since depression is the psychological disorder not intrinsically provoked by the disease, most commonly experienced by individuals with MS,11 12 we hypothesised that the relationships between health-related qualify of life and the MS-associated fatigue would be mediated by depressive symptoms.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with definite MS according to the modified McDonald criteria21 by an experienced neurologist recruited from a local regional hospital in Madrid (Spain) between September 2013 and December 2014 were screened for eligibility criteria. The exclusion criteria included comorbid neurological diseases including herniated disc and other disorders of the spine, renal disease, cancer, diabetes mellitus, other psychiatric diseases and a Mini Mental State Examination score <25.22 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. All procedures were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were recruited during their routine neurological visits and were screened and explored during a stationary phase of the disease. Patients completed a demographic and clinical questionnaire including age, sex, weight, height, medication and history of pain. Subjects underwent a neurological examination, and their neurological impairment was rated using the Expanded Disability Status Scale.23

MS-related fatigue

MS-related fatigue was assessed using the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS).24 The FIS is a 40-item questionnaire that includes three subscales assessing the impact of self-perceived fatigue on cognitive functioning (10 items), physical functioning (10 items) and psychosocial functioning (20 items). Patients rate on a 5-point Likert scale if fatigue caused problems during the previous month (0: no problem; 4: extreme problem). The total score ranges from 0 to 84 points, where higher scores represent more fatigue. This questionnaire has exhibited good test–retest reliability and validity in people with MS.25 In this study, the validated Spanish version of the FIS was used as the main outcome.26

Depression

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II. It consists of 21 items that assess the affective, cognitive and somatic symptoms of depression.27 Patients choose from a group of sentences that best describe how they had been feeling in the preceding 2 weeks. The score ranges from 0 to 63 points, where higher score suggests higher level of depressive symptoms.28 This questionnaire has exhibited good internal consistency and good convergent and divergent validity in individuals with MS.29

Health-related quality of life

The Short-Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) was used to assess health-related quality of life. This questionnaire assesses eight domains, namely physical function, physical role, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role-emotional and mental health.30 Each domain is standardised on scores ranging from 0 to 100 points, where higher scores represent better quality of life. The SF-36 has shown the ability to discriminate between subjects with health problems and asymptomatic individuals.31 32 In the current study, the validated Spanish version of the SF-36 questionnaire was used.33

Statistical analysis

Means, SD and CIs were calculated to describe the sample. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that all quantitative data exhibited a normal distribution. To determine the relationship between fatigue and the remaining variables, that is, depression and health-related quality of life domains, different Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were first assessed.

Second, a path model with maximum likelihood estimation was applied to evaluate the effects of depression between the variables significantly associated with fatigue using the AMOS computer program.34 A path model is defined as a diagram relating independent (exposure), intermediary (mediating) and dependent (outcome) variables.35 In our hypothesised model, fatigue was the dependent variable, health-related quality of life domains were the independent variables, and depression the intermediate, mediating variable of fatigue. In a path analysis, single arrows indicate causation between intermediary and dependent variable. Further, arrows also connect the error terms with their respective intermediary variables. Double arrows indicate correlation between pairs of independent variables. The path coefficient is a standardised regression coefficient (beta) showing the direct effect of an independent variable (health-related quality of life domain) on the dependent (fatigue) variable. Indirect effects occur when the relationship between two variables (eg, fatigue and mental health) is mediated by one or more variables (ie, depression).

Previous conditions from data were assessed: linearity, additivity, interval-level data, recursivity, low multicollinearity and adequate sample size.36 Confirmation of the adequacy of the model was conducted within absolute fit indices.37 38 AMOS provides several fit indices that are largely independent of the sample size: the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), whose value reference is at 90 to consider an acceptable model39; and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), which are also adequate if their values are over 0.90.38 Finally, within parsimony adjustment indices, the error of the root mean square approximation (RMSEA) whose values <0.08 or less is good.40 There was no missing data since the sample was composed by the final subjects satisfying all inclusion criteria (n=108).

Results

One hundred and twenty (n=120) consecutive subjects with MS were screened for eligibility criteria. One hundred and eight (n=108, 90%) (54% women; mean age 44±8 years; height 170±9 cm; weight 71±15 kg) satisfied all the eligibility criteria, agreed to participate and signed the informed consent. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: previous surgery (n=6), pregnancy (n=2) and older than 65 years old (n=4). The demographic and clinical data of the total sample are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and specific disease clinical data for the total sample (n=108)*

| Gender (male/female), n (%) | 49 (45)/59 (55) |

| Age (years) | 44±8 (42 to 45) |

| Height (cm) | 170±9 (168 to 172) |

| Weight (kg) | 71.5±15 (68 to 75) |

| Disease course, n (%) | |

| Relapsing-remitting | 80 (74) |

| Secondary progressive | 19 (18) |

| Primary progressive | 8 (8) |

| Disease duration (years) | 12.5±8.0 (11.0 to 14.2) |

| EDDS (0–10) | 3.4±1.7 (3.1 to 3.8) |

| FIS (total score, 0–84) | 38.7±19.2 (34.9 to 42.5) |

| Physical function (SF-36, 0–100) | 55.5±27.8 (49.9 to 60.9) |

| Physical role (SF-36, 0–100) | 49.5±40.7 (41.4 to 57.6) |

| Bodily pain (SF-36, 0–100) | 66.2±23.5 (62.5 to 70.8) |

| General health (SF-36, 0–100) | 44.8±21.1 (40.6 to 49.1) |

| Vitality (SF-36, 0–100) | 44.9±19.8 (40.9 to 48.8) |

| Social function (SF-36, 0–100) | 71.2±24.2 (66.4 to 76.0) |

| Emotional role (SF-36, 0–100) | 78.3±35.9 (71.2 to 85.4) |

| Mental health (SF-36, 0–100) | 68.6±16.4 (65.4 to 71.9) |

| BDI-II (0–63) | 10.2±6.7 (8.8 to 11.5) |

*Data are mean±SD (95% CI).

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; FIS, Fatigue Impact Scale; SF-36, Short-Form Health Survey 36.

Correlation analysis

Table 2 shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between variables included in the path model showing significant association with fatigue. Fatigue was significantly negatively associated (higher score) with bodily pain (r=−0.48, P<0.01), physical function (r=−0.31, P<0.01) and mental health (r=−0.42, P<0.01), and also significantly positively associated with depression (r=0.47, P<0.01): the higher the self-perceived fatigue, the worse physical function, the worse mental health, the higher bodily pain or the higher depressive symptom. Depression was also negatively associated with bodily pain (r=−0.40, P<0.01) and mental health (r=−0.61, P<0.01): the worse mental health or higher presence of bodily pain, the higher the level of depression.

Table 2.

Pearson product-moment correlation matrix for the study variables included in the path model

| Mean | SD | 95% CI | Kurtosis | Skewness | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Fatigue (Fatigue Impact Scale, 0–84) | 38.7 | 19.2 | 34.9 to 42.5 | −0.48 | 0.22 | ||||

| Bodily pain (0–100) | 66.2 | 23.5 | 62.5 to 70.8 | −0.46 | −0.28 | −0.488** | |||

| Physical function (0–100) | 55.5 | 27.8 | 49.9 to 60.9 | −1.20 | 0.00 | −0.308** | 0.072 | ||

| Mental health (0–100) | 68.6 | 16.4 | 65.4 to 71.9 | −0.70 | −0.15 | −0.424** | 0.468** | 0.106 | |

| Depression (0–63) | 10.2 | 6.7 | 8.8 to 11.5 | 0.33 | 0.72 | 0.475** | −0.403** | −0.184 | −0.606** |

Skewness SE=0.23; kurtosis SE=0.46.

**P < 0.01.

Path analysis

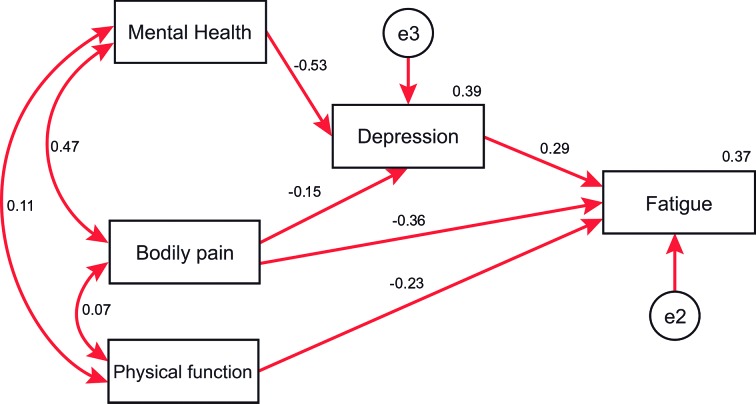

The hypothesised model fit of the data was excellent with GFI of 0.98, AGFI of 0.91, CFI of 0.98, TLI of 0.94 and NFI of 0.97. Further, the RMSEA was 0.08. Figure 1 displays the parameter estimates (standardised solution).

Figure 1.

Path analyses relating mental health, bodily pain and physical function with fatigue with the intermediate effect of depression. Standardised direct path coefficients are presented. In this model mental health predicts depression, while the independent variable (fatigue) is predicted by depression and also directly by physical activity. The straight arrows represent regression paths for presumed causal relationships, while the curved double-headed arrows represent assumed correlations among the variables.

According to the direct effects, a significant path was noted from mental health (B=−0.53, P<0.01) to depression, with an SE of 0.035. Likewise, significant paths were also indicated between physical function (B=−0.23, P<0.01, SE=0.054), bodily pain (B=−0.36, P<0.01, SE=0.070) and depression (B=0.29, P<0.01, SE=0.025) on fatigue. The direct effect from bodily pain on depression did not reach significance (B=−0.15, P=0.07, SE=0.024). Furthermore, significant indirect effects in the path analysis model from bodily pain to fatigue mediated by depression (B=−0.04, P<0.01, SE=0.031), and from mental health to fatigue also mediated by depression (B=−0.16, P<0.01, SE=0.015), were observed. Overall, the amount of fatigue explained by all predictors in the model was R2=0.37.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that depression mediates the relationship between some health-related quality of life domains, such as mental health and bodily pain, and fatigue in individuals with MS. These results support the assumption that depression is related to fatigue and that it can mediate the effects of health-related quality of life in individuals with MS.

Our findings have shown, first and in accordance with prior literature,9 10 14–17 that depression is a psychological factor directly associated with fatigue in people with MS. However, previous studies have not investigated the mediating effects of depression on the association with other variables. The current study showed that depression mediated the association between some health-related quality of life domains, such as bodily pain and mental health, and fatigue, suggesting that depressive levels mediate the contribution of quality of life to related fatigue. The relevance of depression was further supported by the fact that depression also showed an effect on self-perceived fatigue in our sample of subjects with MS. This means that depression has an influence on fatigue, but also other mediating influences in other outcomes. This finding is quite interesting if we consider that the depression symptoms of our sample of people with MS were low since scores reflected minimal or mild signs of depression.27 It is plausible that higher levels of depression may reveal stronger relationships.

The association between mental health and fatigue in MS is not new since some studies have reported that fatigue contributes to mental fatigue, worse emotional well-being and worse cognitive performance.41 42 The novelty of the current study was that the effect of mental health on fatigue was mediated by depression. This is an expected finding, since depression contributes to worse cognitive performance.13 It would be reasonable to consider that individuals with MS suffering from fatigue experience worse cognitive function, which may in turn provoke depressive symptoms, and therefore increase the self-perceived fatigue. Bidirectional reinforcement between mental health and depression can create a vicious cycle by promoting self-perceived fatigue in people with MS.

Another health-related quality of life domain that was directly associated with fatigue was bodily pain. This was expected since the presence of pain also contributes to fatigue.43 Nevertheless, similar to mental health, the effect of bodily pain on fatigue was mediated by depression. It can be hypothesised that pain induces depression and that pain will promote a worse fatigue self-perception. This hypothesis is also supported by another study that used a similar analysis with our study, where higher pain levels were associated with fatigue, which in turn were associated with higher depression.44 Current and previous findings suggest that proper management of depressive symptoms would be a key element in the treatment of pain in individuals with MS, although further studies are needed.

The path model also identified that physical function was associated with self-perceived fatigue in our sample of individuals with MS. In this case, the association of physical function and fatigue was not mediated by depression, supporting a direct effect between these variables. These findings are similar to the results by Turpin et al,45 who found that patients with MS with greater fatigue and disability exhibited poorer physical activity. Again, it is expected that individuals reporting greater fatigue have lower physical activity. It is possible that this association could influence other psychological outcomes included in our path analysis, since fatigue may contribute to depression by reducing physical function as a result of lack of energy.46 These associations support a complex interaction among physical outcomes, depressive symptoms and fatigue.

With uncertainty over biological mechanisms accounting for these interactions, the current results have important clinical implications. Our results indicate that depression, that is, an emotional status not directly caused by the condition, plays a relevant role in the relationship between fatigue and health-related quality of life in people with MS. Therefore, our results suggest that proper management of depression can be effective in improving self-perceived fatigue in people with MS by impacting mental health and bodily pain. It is possible that management of fatigue by treating depressive symptoms would lead to an increase in physical activity in these individuals. This hypothesis is supported by a recent review reporting that proper psychological management produced improvements in both psychological and physiological outcomes in patients with MS.47 However, future randomised clinical trials are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

There are a number of limitations that should be recognised. First, we used a cross-sectional design; therefore, the cause and effect relationships between the variables cannot be inferred. Second, the sample was composed of patients with MS recruited from different urban hospitals. Therefore, extrapolation of the current results to more diverse populations should be conducted with caution. Additionally, we used a non-probabilistic sampling for a finite population to calculate our sample size. This was conducted applying a 95% confidence level and a sampling error for the final set of participants under 5%. Although we could not estimate a priori sample size, we believe that our sample is representative of the population. Third, the level of depressive symptoms in our sample of patients with MS was lower than expected. In fact, scores showed that almost all participants exhibited small depressive levels. It is possible that the presence of higher symptoms of depression can lead to further associations or effects. Fourth, we should consider that health-related quality of life was assessed with a general, but not disease-specific, questionnaire. It is possible that the use of an MS-specific quality of life questionnaire, that is, Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life (MSQoL-54), would lead to other potential associations. Finally, other potential confounder variables, such as sleep disturbances or anxiety, that could give a broader vision of the biopsychosocial model approach were not included. This study would benefit from longitudinal data to further determine the impact of proper management of depressive symptoms on the identified associations over time in patients with MS.

Conclusions

This study found that depression mediated the relationship between mental health and bodily pain, but not the association of physical activity, and fatigue in people with MS. These results support the assumption that depression is directly related with fatigue and that it can mediate the effects of health-related quality of life in individuals with MS. Future longitudinal studies will help determine the clinical implications of these findings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study concept and design. JJF-M and CFdlP did the main statistical analysis and interpretation of data. CFdlP, MC-M and PP-B contributed to drafting the report. MCM, EN-P and PP-B provided administrative, technical and material support. EN-P and MPdH-T supervised the study. All authors revised the text for intellectual content and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the local ethical research committee of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (HUFA 11/087), Madrid, Spain.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.vp955.

References

- 1. Melcon MO, Correale J, Melcon CM. Is it time for a new global classification of multiple sclerosis? J Neurol Sci 2014;344:171–81. 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fernández O, Fernández V, Guerrero M, et al. . Multiple sclerosis prevalence in Malaga, Southern Spain estimated by the capture-recapture method. Mult Scler 2012;18:372–6. 10.1177/1352458511421917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Otero-Romero S, Roura P, Solà J, et al. . Increase in the prevalence of multiple sclerosis over a 17-year period in Osona, Catalonia, Spain. Mult Scler 2013;19:245–8. 10.1177/1352458512444751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Candeliere-Merlicco A, Valero-Delgado F, Martínez-Vidal S, et al. . Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in health district III, Murcia, Spain. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;9:31–5. 10.1016/j.msard.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shah A. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2009;20:363–72. 10.1016/j.pmr.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braley TJ, Chervin RD. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Sleep 2010;33:1061–7. 10.1093/sleep/33.8.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cavallari M, Palotai M, Glanz BI, et al. . Fatigue predicts disease worsening in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2016;22:1841–9. 10.1177/1352458516635874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T, Oleen-Burkey M. North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis. Fatigue characteristics in multiple sclerosis: the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:100 10.1186/1477-7525-6-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nourbakhsh B, Julian L, Waubant E. Fatigue and depression predict quality of life in patients with early multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:1482–6. 10.1111/ene.13102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kargarfard M, Eetemadifar M, Mehrabi M, et al. . Fatigue, depression, and health-related quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:431–7. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marrie RA, Patten SB, Tremlett H, et al. . Sex differences in comorbidity at diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology 2016. [Epub ahead of print 9 Mar 2016]. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, et al. . The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler 2015;21:305–17. 10.1177/1352458514564487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nunnari D, De Cola MC, D’Aleo G, et al. . Impact of depression, fatigue, and global measure of cortical volume on cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–7. 10.1155/2015/519785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fricska-Nagy Z, Füvesi J, Rózsa C, et al. . The effects of fatigue, depression and the level of disability on the health-related quality of life of glatiramer acetate-treated relapsing-remitting patients with multiple sclerosis in Hungary. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;7:26–32. 10.1016/j.msard.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Miletich RS, et al. . Fatigue in multiple sclerosis and its relationship to depression and neurologic disability. Mult Scler 2000;6:181–5. 10.1191/135245800701566052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards KA, Molton IR, Smith AE, et al. . Relative importance of baseline pain, fatigue, sleep, and physical activity: Predicting change in depression in adults with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:1309–15. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kroencke DC, Lynch SG, Denney DR. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: relationship to depression, disability, and disease pattern. Mult Scler 2000;6:131–6. 10.1191/135245800678827590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Šabanagić-Hajrić S, Suljić E, Kučukalić A. Fatigue during multiple sclerosis relapse and its relationship to depression and neurological disability. Psychiatr Danub 2015;27:406–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanriverdi D, Okanli A, Sezgin S, et al. . Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis in Turkey: relationship to depression and fatigue. J Neurosci Nurs 2010;42:267–73. 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3181ecb019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berrigan LI, Fisk JD, Patten SB, et al. . Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: direct and indirect effects of comorbidity. Neurology 2016. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. . Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. 10.1002/ana.22366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444–52. 10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, et al. . Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18(Suppl 1):S79–83. 10.1093/clinids/18.Supplement_1.S79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mathiowetz V. Test-retest reliability and convergent validity of the fatigue impact scale for persons with multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther 2003;57:389–95. 10.5014/ajot.57.4.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benito-León J, Martínez-Martín P, Frades B, et al. . Impact of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: the Fatigue Impact Scale for daily use (D-FIS). Mult Scler 2007;13:645–51. 10.1177/1352458506073528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK, et al. . Beck depression inventory. 2nd ed San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988;8:77–100. 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sacco R, Santangelo G, Stamenova S, et al. . Psychometric properties and validity of beck depression inventory ii in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:744–50. 10.1111/ene.12932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. . SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32. The Canadian Burden of Illness Study Group. Burden of illness of multiple sclerosis: part II: quality of life. Can J Neurol Sci 1998;25:31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alonso J, Prieto L, Antó JM. [The spanish version of the SF-36 health survey (the sf-36 health questionnaire): an instrument for measuring clinical results]. Med Clin 1995;104:771–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 users guide. Chicago: Small waters, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Duncan OD. Path analysis: sociological examples. Am J Sociol 1966;72:1–16. 10.1086/224256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed New York: Guilford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. Advanced in factor analysis and structural equation models. Cambridge: M.A. Abl, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 1990;107:238–46. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu Li‐tze, Bentler PM. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Mod 1999;6:1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steiger JH, Lind C. Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Iowa City, IA: Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychometric Society, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lerdal A, Celius EG, Krupp L, et al. . A prospective study of patterns of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:1338–43. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01974.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ukueberuwa DM, Arnett PA. Evaluating the role of coping style as a moderator of fatigue and risk for future cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2014;20:751–5. 10.1017/S1355617714000587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shahrbanian S, Duquette P, Ahmed S, et al. . Pain acts through fatigue to affect participation in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res 2016;25:477–91. 10.1007/s11136-015-1098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Amtmann D, Askew RL, Kim J, et al. . Pain affects depression through anxiety, fatigue, and sleep in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol 2015;60:81–90. 10.1037/rep0000027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Turpin KV, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, et al. . Deterioration in the health-related quality of life of persons with multiple sclerosis: the possible warning signs. Mult Scler 2007;13:1038–45. 10.1177/1352458507078393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Penner IK, Bechtel N, Raselli C, et al. . Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: relation to depression, physical impairment, personality and action control. Mult Scler 2007;13:1161–7. 10.1177/1352458507079267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pagnini F, Bosma CM, Phillips D, et al. . Symptom changes in multiple sclerosis following psychological interventions: a systematic review. BMC Neurol 2014;14:222 10.1186/s12883-014-0222-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.