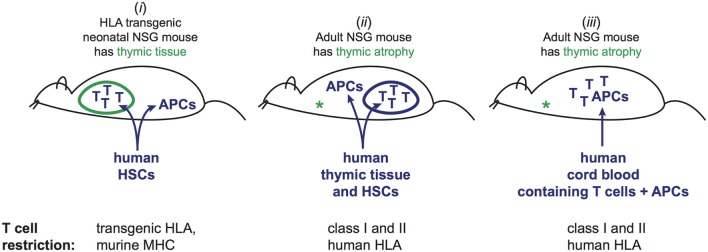

Figure 1.

Three different approaches to generate mice engrafted with human T cells and cognate human antigen-presenting cells (APCs). (i) Injection of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) into neonatal mice. Human T cells and APCs develop from the HSCs. T cells undergo selection in murine thymus based on interactions with murine cells. By using mice that are transgenic for one or more HLA molecules, and HSCs bearing HLA alleles that match the transgenes, a fraction of the mature human T cells in the periphery will be able to recognize the human APCs, while others are restricted by murine antigen presenting molecules that are also present in the thymic environment. This method does not recapitulate the full repertoire of T cell restriction for human antigen presenting and may not produce tolerance to human peptides presented by the restricting HLA molecules, but is associated with little or no graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). (ii) Adult NSG mice, which lack murine thymic tissue due to atrophy, are injected with human HSCs. Concurrently, a fragment of human thymic tissue is surgically implanted. Human T cells and APCs develop from the HSCs, and the thymic fragment develops into a viable organoid. T cells undergo selection in the human thymic organoid based on interactions with human thymic cells. The resulting T cell repertoire includes restriction for the full panoply of autologous HLA molecules. However, signs of chronic GVHD typically manifest within 4–6 months. (iii) Human umbilical cord blood engraftment of adult NSG mice. Mature T cells (selected in the baby’s thymus) are transplanted along with autologous APCs. Human T cells typically persist for at least 3 months, but signs of GVHD may become apparent after about 2 months.