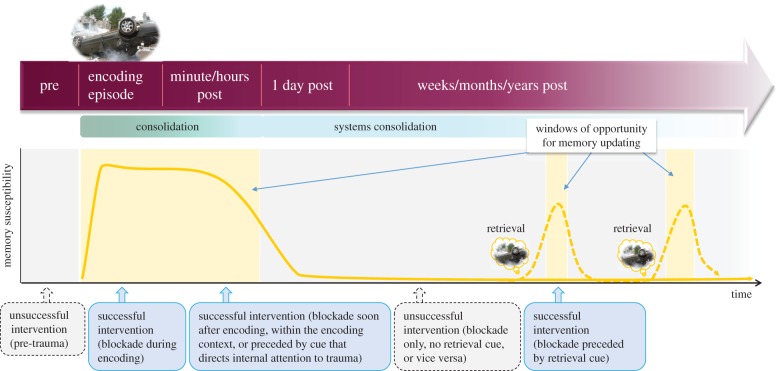

Figure 3.

In the hours after an experience, memories are believed to go through an initial labile phase, before being stored into stable long-term memory, i.e. consolidation. The purple arrow depicts different time intervals with respect to the encoding of an aversive episode. Green gradients below indicate the putative processes of memory encoding and consolidation that occur during these different intervals, with systems consolidation referring to process by which memories become less hippocampus-dependent and integrated into a wider semantic network. Recent insights from studies in non-human animals suggest that (certain aspects of) memories are not necessarily permanent. Instead, they may become transiently malleable upon their reactivation, rendering them susceptible to interference or updating before returning to a fixed state, a process referred to as ‘reconsolidation’. This offers a second window of opportunity to interfere with consolidated memory (shown by yellow background shaded areas). Successful interventions (blue arrows) need to be timed such that the blockade interferes with memory when it is in an active, susceptible state (indicated by the dotted yellow line)—either in the first hours after an experience, or at later time intervals after a retrieval procedure (e.g. reactivation through reminder cues). In the first hours after an experience, blockade procedures may also need to be preceded by cues that orient attentional resources to the event in order for procedures to successfully interfere with it, for example when the intervention is delivered in a context other than the one in which the trauma occurred. Unsuccessful interventions, timed when memories do not yet exist, or are in a fixed state (i.e. not recently retrieved), are indicated by grey arrows with dotted outlines.