The story of the successful management of disseminated testicular cancer (TC) is well known and is listed among the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s top five accomplishments in cancer medicine in the last 50 years.1,2 Using the development of highly active systemic chemotherapy as a backbone, global outcomes achieved in experienced centers or collaborative groups are unparalleled. Now, many patients presenting with TC receive no therapy beyond orchiectomy. Those who do present with or develop more advanced disease are most often rendered disease free with inexpensive, relatively brief treatments. More than 95% of all patients are cured and most enjoy high-quality, long-term survivorship.

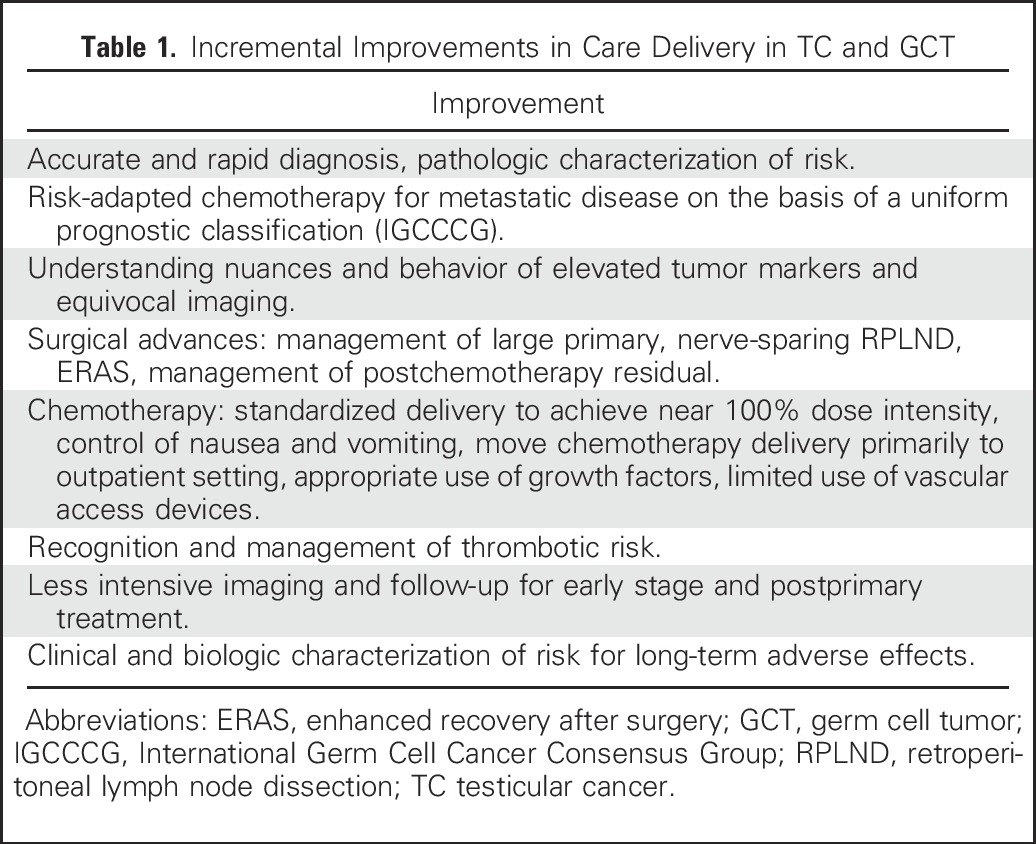

Since the early 1970s, improvements in outcomes for patients with germ cell tumors (GCTs) have been achieved through breakthroughs such as the discovery and application of cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and also by less spectacular but continuous incremental innovation in all aspects regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of testicular cancer. These innovations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Incremental Improvements in Care Delivery in TC and GCT

High-volume centers and cooperative groups have the opportunity to gain broad experience, develop dedicated multidisciplinary teams, and build clinical registries, large datasets, and biorepositories. This comprehensive approach facilitates research, drives innovation, and helps engineer improved care delivery and improved value.

Given that TC is an uncommon disease, few institutions have substantial and sustained experience in expert management of GCTs. As such, globally, most patients are diagnosed and treated in low-experience environments. Such environments do not have the opportunity to build multidisciplinary teams or have many repetitive opportunities to hone decision-making and learn from errors over time. Herein, we present the evidence supporting the favorable effect on patient care of collaboration with highly experienced teams and groups on global outcomes in TC.

The Hypothesis: Experience Matters

We hypothesize that there is an experience/outcome effect in the management of GCT with institutions or collaborative groups that treat many patients, achieving better and more consistent results at lower cost with fewer complications. If true, this suggests that each patient would be best served with early and continuous input by a multidisciplinary specialized team including experienced medical oncologists, urologists, oncology nursing, pathologists, and radiologists, along with the patient and local care providers.

Evidence Supporting Experience as an Important Component of Improved Outcomes in GCTs

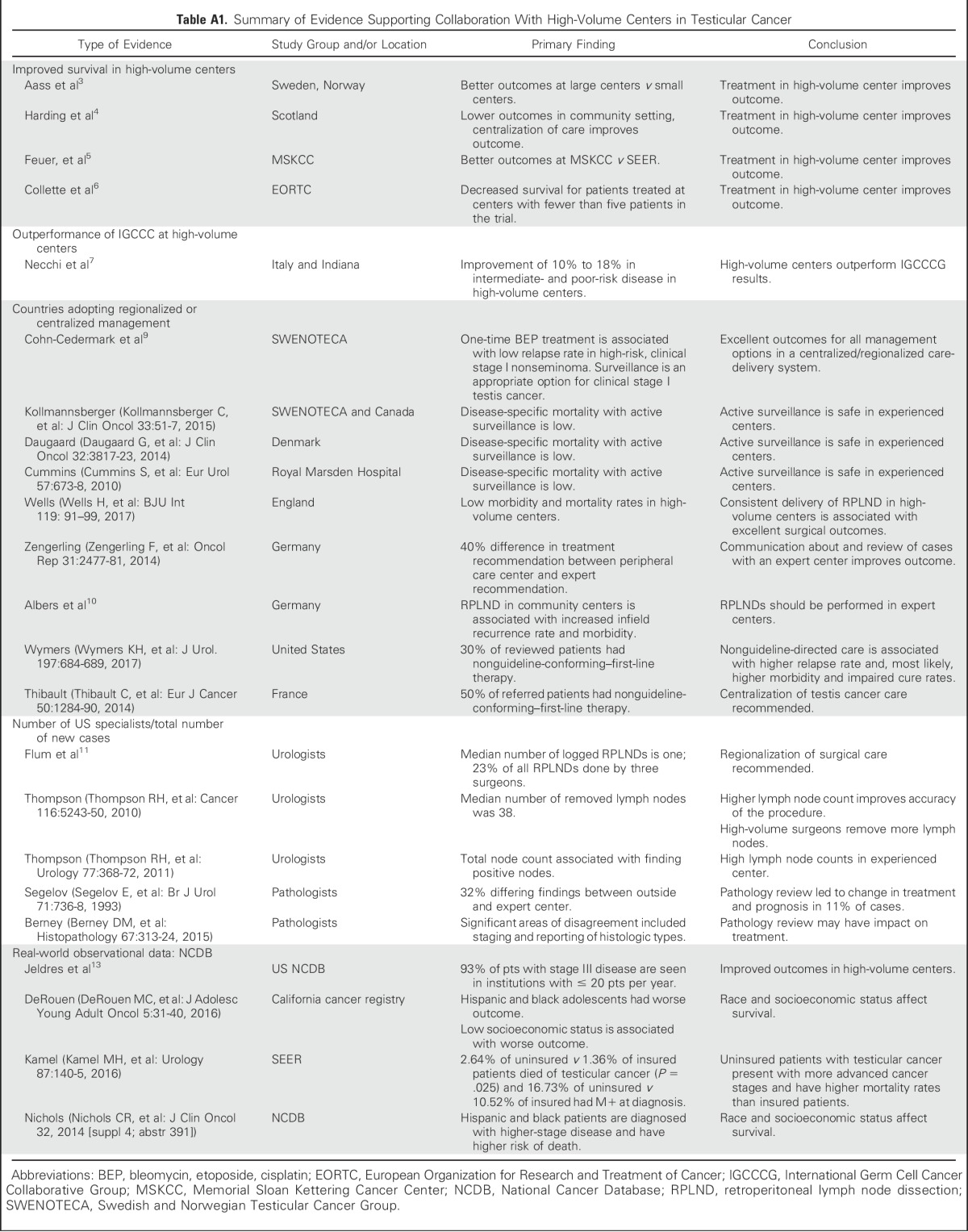

That experience matters in GCT management has been noted almost since the discovery of cisplatin as a highly active agent in management of disseminated GCT. Early analyses from the Swedish Norwegian Testicular Cancer Project and from western Scotland suggested strongly that, for patients with advanced disseminated GCT, there was a clinically significant difference in survival for those treated at a large single center compared with those treated at smaller surrounding community sites.3,4 Feuer et al5 reported findings of an early analysis of the US SEER registry somewhat after the widespread dissemination of cisplatin. Whereas a dramatic improvement in outcomes in this population-based registry was seen over the first years after the introduction of cisplatin, results plateaued and were noticeably inferior to those seen at a high-volume single institution. A significant minority of the patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in this study received chemotherapy by the referring community oncologist after referral to MSKCC, with a postchemotherapy re-evaluation at MSKCC to determine whether surgery was necessary. It was an early example of the value of leveraging the expertise of a specialized center.6 Other examples are given in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Across the world, high-volume institutions and collaborator groups consistently outperform the International Germ Cell Consensus Classification predictive model in good, intermediate, and poor prognosis disease. Current data suggest that care in high-volume centers or collaborator groups exceed International Germ Cell Consensus Classification predictions in good-prognosis disease by 5%, and by 10% to 15% in intermediate and poor prognosis, respectively.6,7 In 1999, these issues were highlighted by Feuer et al.8 In addition to citing the existing evidence, the authors called for treatment of patients with GCT by experts at high-volume centers.

These calls have been heeded variably around the world. Some countries have taken this to the logical extension of having all patients managed under central guidance and triage of complicated patients to high-volume centers. Despite having to cover large and sparsely populated geographies, the Swedish and Norwegian Testicular Cancer Group has been able to coordinate care and effectively disseminate the experience of high-volume centers to achieve consistent outcomes for these populations similar to the best single institutions in the world.9 Other national or regional organizational efforts are described in Appendix Table A1.

Further evidence and opinions have been forthcoming recently. Albers et al,10 in a randomized clinical trial, demonstrated inferior outcomes and complications (infield relapses) when primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissections (RPLND) were performed at community centers. Additional examples are listed in Appendix Table A1.

Current Status of Provider and Institutional Experience in the United States

Recent analysis shows that 52% of all RPLND procedures were performed by a urologist who logged one or two cases in a 6-month period, and just three urologists performed approximately 25% of the RPLNDs performed for TC in the United States.11 RPLND is a procedure where the surgical quality is essential for the outcomes in regard to complications, relapses, survival, and quality survivorship. Ratios of new patients with TC to various specialists are described in Appendix Table A1. The average number of new patients with TC seen by a general community medical oncologist or radiation oncologist is less than one new patient annually.

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) available from the American College of Surgeons provides high-level registry data for patients with cancer in the United States.12 Approximately 1,500 institutions report to the NCDB, yet fewer than 20 see more than 20 new patients with TC annually, and the median institutional volume of patients with stage III disease per institution is two. For TC, although detailed information is lacking, the number of patients represented in the NCDB (79,120 patients over the most recent 10-year period) and some baseline conclusions for this uncommon, highly curable malignancy could be drawn.13 These include slow uptake of modern principles of management, disparity gaps for racial minorities and the poor, and a robust correlation with improved survival of patients with advanced stage disease in high-volume centers.13

In a disease with such high survival rates, it is impossible to find level I evidence supporting improved outcomes on the basis of institutional volume alone. However, all data and expert consensus strongly support improved outcomes in TC being achieved at high-volume centers and through the use of collaborator groups. In the US data, there are limitations to the NCDB data set analyzed, including incomplete clinical data; inability to measure reasons for or against referral; the possibility that sicker patients, poorer patients, and patients in extremis may not be able to be referred to high-volume centers; and the influence of access, financial, and educational status. In the opposite direction, it is difficult to measure the potentially salubrious effects of direct consultation and indirect oversight and second opinions (a long and strong tradition in TC) with actual care being rendered at the local institution on favorable outcomes and avoidance of errors. All told, however, and using an Occam’s razor approach, the mostly likely explanation is the simple one—in this uncommon disease where best outcomes require precision in management and multidisciplinary decision-making, experience and repetitions do matter.

The Case for Collaboration in Management of GCTs in the United States

In GCT guideline development groups around the world, issues of inconsistent care, overtreatment, inconsistent decision making, and inexperienced providers are raised frequently but often “sotto voce.” We have observed that concerns regarding offending colleagues and impeding competition are often raised as reasons against forceful declaration of the importance of involving experienced teams for best multidisciplinary decision making and management. For instance, only recently do most guideline sets reflect that all retroperitoneal lymphadenectomies should be performed in high-volume centers, and that radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment of stage I seminoma should be uncommon.

There are significant barriers to physically accessing the few high-volume centers for GCTs in the United States, even among willing patients and referring providers. Chief among these are the geographic distances involved with significant risk of unreimbursed travel and housing expenses, and insurance-related barriers to access to specialty centers. There are a number of community oncologists who have received disrespect, poor service, and poor follow-up from high-volume centers and are understandingly reluctant to facilitate referrals.

What is particularly exciting in this modern era is that we now have the bidirectional capacity to leverage knowledge and experience over distance cheaply and comprehensively. Potential patients within large systems can be identified electronically at the time of suspicion of the diagnosis, diagnostic workup pathways can be inserted into electronic medical records, and pathology slides can be digitized and distributed electronically to centers for expert review. Sharing of images and laboratory results is routine and the guided gathering of patient-reported inputs and outcomes is becoming standard. With the availability of telepresence, expertise virtually can show up on any doorstep.

The on-demand economy is all around us where access is more important than ownership. Some medical groups are starting to view expertise and oversight as a commodity deliverable in real time to the point of care. While business plans and legal issues await resolution, the capability exists to move deep experience and expert team-based care locally for the benefit of almost all patients.

In summary, there appears to be a clear relationship between institutional experience and better outcomes. Although this is not a new insight, we think it is particularly important to discuss this in the modern era and begin remediation of consequences of care in low-experience environments. Recent data have strengthened the vector pointing toward experience as a critical set piece in the management of these uncommon and highly curable malignancies. Instant transmission of images, pathology material, and laboratory values is routine and there is increased availability of virtual presence. We call for the following:

High-volume regional centers to redouble their efforts to create effortless access to their experience by building real-time capacity to ingest primary diagnostic and predictive information, including patient preference for those newly diagnosed with GCTs, as well as developing outbound capacity to communicate recommendations and ongoing oversight effectively to local providers and to these patients.

Development of community consensus on what best defines a high-volume center and continuous monitoring of performance to maintain confidence in high-volume, quality centers of excellence.

Community providers to join in building such capacity and support these efforts with indirect or direct referrals of all patients with GCT from onset to such collaborative regional expert systems.

Clinical investigators to put increased emphasis on classic clinical trials as well as investigations including biomarker-driven decision making, novel population-based studies using high-quality observational data, and new cancer care delivery research to address areas such as comparative effectiveness, care disparities, secondary use of big data, international management of GCT, and continued study of short- and long-term quality of life and late effects.

Payers, large employers, and governments to catalyze these efforts by insuring coverage for the work and infrastructure required to build and sustain these regional virtual centers of excellence as well as support triage of complex patients or those requiring high-technology approaches to high-volume centers.

Patients to understand the value of collaborative care for uncommon conditions and advocate with their local provider to participate in information sharing with organized expert teams.

We believe experience gaps can be remediated. Selective triage, commitment to collaboration, and modern methods of information and knowledge exchange can facilitate discussion on any case and expedite referral when needed. Expert care and excellent outcomes can be delivered close to home in most cases. Hence, we believe that all patients with TC, whenever possible, should be managed through direct or indirect contact with a high-volume referral center.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This report is in honor of Dr Lawrence Einhorn, and in memory of Drs Stephen D. Williams and John Donohue, who reminded us of our privilege in gaining experience in care of patients with testicular cancer and our obligation to share this experience without restriction. We appreciate the opportunity afforded us by the American College of Surgeons and the National Cancer Database to analyze these data. We thank the Virginia Mason Cancer Center, Section of Urology, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Benaroya Research Institute, the Adolescent and Young Adult Committee of SWOG and Testicular Cancer Commons for administrative, statistical, and scientific input and support.

Appendix

Table A1.

Summary of Evidence Supporting Collaboration With High-Volume Centers in Testicular Cancer

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Administrative support: Claudio Jeldres

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Practice Makes Perfect: The Rest of the Story in Testicular Cancer as a Model Curable Neoplasm

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Torgrim Tandstad

No relationship to disclose

Christian K. Kollmannsberger

Honoraria: Pfizer, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Scientific and Medical Affairs

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Novartis, Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, Novartis

Bruce J. Roth

No relationship to disclose

Claudio Jeldres

No relationship to disclose

Silke Gillessen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bayer, CureVac (Inst), Dendreon, Janssen-Cilag, Millennium, Novartis (Inst), Orion Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, Active Biotech (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Ferring (Inst), MaxiVax, AAA International (Inst), Roche (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Method for biomarker (WO 3752009138392 A1)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Several companies

Other Relationship: ESSA, Nektar, ProteoMediX

Karim Fizazi

Honoraria: Janssen, Sanofi, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Clovis Oncology, Genentech, Janssen-Cilag, CureVac, Orion Pharma, Sanofi

Siamak Daneshmand

Consulting or Advisory Role: Photocure, Taris, Pacific Edge, Allergan (I)

Research Funding: Photocure, Taris

William T. Lowrance

Consulting or Advisory Role: MDxHealth, Myriad Genetics

Research Funding: Myriad Genetics (Inst), Argos Therapeutics (Inst), GenomeDx (Inst), MDxHealth (Inst)

Nasser H. Hanna

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Costantine Albany

Stock or Other Ownership: Advaxis

Honoraria: Sanofi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Seattle Genetics

Speakers' Bureau: Bayer, Sanofi

Research Funding: Astex Pharmaceuticals

Richard Foster

No relationship to disclose

Gabriella Cohn Cedermark

No relationship to disclose

Darren R. Feldman

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Gilead Sciences (I)

Research Funding: Novartis

Thomas Powles

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Roche

Mark A. Lewis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Boehringer Ingelheim, Shire

Peter Scott Grimison

Research Funding: Tilray (Inst), Specialised Therapeutics Australia (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), MSD (Inst), Gilead (Inst), Boston Biomedical (Inst), Tigermed (Inst), Halozyme (Inst)

Douglas Bank

Employment: Scribe America (I)

Christopher Porter

No relationship to disclose

Peter Albers

No relationship to disclose

Maria De Santis

Honoraria: Pierre Fabre, Roche, Bayer, Novartis, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pierre Fabre, Roche, Oncogenex, Synthon, Ipsen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bayer, Sanofi, Ferring, Pfizer/Merck, ESSA, AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Bayer, Janssen, Ipsen, Astellas Pharma

Sandy Srinivas

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Pfizer, Medivation, Novartis

Speakers' Bureau: Genentech

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

George J. Bosl

No relationship to disclose

Craig R. Nichols

Research Funding: Intermountain Precision Genomics Cancer Research Clinic (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Seattle Genetics

REFERENCES

- 1.Einhorn LH. Testicular cancer as a model for a curable neoplasm: The Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation Award Lecture. Cancer Res. 1981;41:3275–3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg K. https://www.asco.org/about-asco/press-center/news-releases/asco-50th-anniversary-poll-names-top-5-advances-past-50-years ASCO 50th anniversary poll names the top 5 advances from the past 50 years.

- 3.Aass N, Klepp O, Cavallin-Stahl E, et al. Prognostic factors in unselected patients with nonseminomatous metastatic testicular cancer: a multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:818–826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.5.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding MJ, Paul J, Gillis CR, et al. Management of malignant teratoma: does referral to a specialist unit matter? Lancet. 1993;341:999–1002. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91082-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feuer EJ, Frey CM, Brawley OW, et al. After a treatment breakthrough: a comparison of trial and population-based data for advanced testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:368–377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collette L, Sylvester RJ, Stenning SP, et al. Impact of the treating institution on survival of patients with “poor-prognosis” metastatic nonseminoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:839–846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.10.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Necchi A, Pond GR, Nicolai N, et al. Suggested reclassification strategy applied to intermediate and poor risk nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT): A two-institution combined analysis J Clin Oncol 342016. suppl; abstr 4546 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feuer EJ, Sheinfeld J, Bosl GJ. Does size matter? Association between number of patients treated and patient outcome in metastatic testicular cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:816–818. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.10.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohn-Cedermark G, Stahl O, Tandstad T. Surveillance vs. adjuvant therapy of clinical stage I testicular tumors - a review and the SWENOTECA experience. Andrology. 2015;3:102–110. doi: 10.1111/andr.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albers P, Siener R, Krege S, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection with one course of bleomycin and etoposide plus cisplatin chemotherapy in the adjuvant treatment of clinical stage I nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors: AUO trial AH 01/94 by the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2966–2972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0899. [Erratum: J Clin Oncol 28:1439, 2010] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flum AS, Bachrach L, Jovanovic BD, et al. Patterns of performance of retroperitoneal lymph node dissections by American urologists: most retroperitoneal lymph node dissections in the United States are performed by low-volume surgeons. Urology. 2014;84:1325–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RT, Stewart AK, Winchester DP. Monitoring the delivery of cancer care: Commission on Cancer and National Cancer Data Base. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;21:377–88, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeldres C, Pham K, Daneshmand S, et al. Association of higher institutional volume with improved overall survival in clinical stage III testicular cancer: Results from the National Cancer Data Base (1998-2011) J Clin Oncol 325s.2014. suppl; abstr 4519 [Google Scholar]