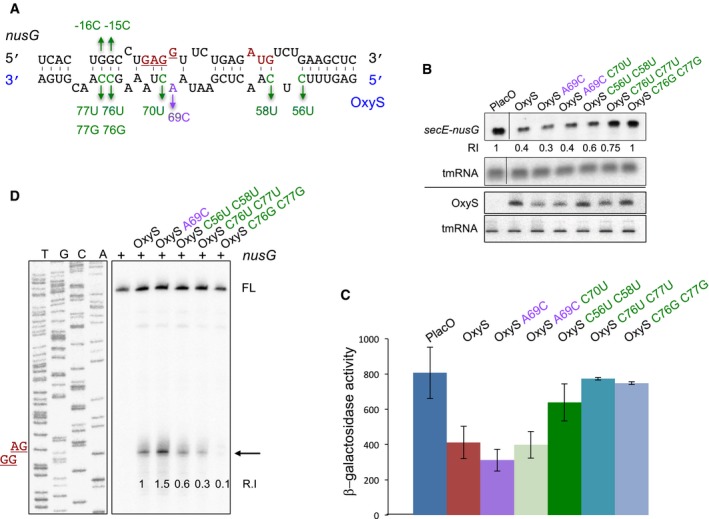

Figure 2. OxyS represses nusG expression.

- Predicted base pairing between nusG and OxyS RNAs. The initiation codon and the Shine–Dalgarno sequence of nusG are marked in red. Suppressor nontoxic OxyS mutants are in green, the highly toxic mutant is in purple.

- Northern analysis of RNA extracted from cells carrying control and OxyS plasmids. Total RNA was extracted from cultures treated at dilution with 1 mM IPTG for 90 min. Samples were analyzed by 1.4% agarose–formaldehyde gel electrophoresis to detect the full‐length transcript of secE‐nusG and tmRNA or 6% urea–PAGE to detect OxyS and tmRNA. The tmRNA served as loading control. The membranes were probed with 5′ end‐labeled OxyS and tmRNA‐specific primers and antisense riboprobe to detect secE‐nusG mRNA. Relative intensity (RI) of secE‐nusG in the presence of control, wild‐type, and OxyS plasmids.

- Cultures (relA::cat, ΔoxySli::frt, lacZ::Tn10, lacI q) carrying Ptac‐nusG‐lacZ (pSC101*; single copy) translational fusion and OxyS plasmids were treated with IPTG (1 mM) at OD600 = 0.1. β‐Galactosidase activity was measured 120 min after treatment. Results are displayed as mean of two to eight biological experiments ± standard deviation.

- Primer extension of in vitro‐synthesized nusG mRNA in the absence or presence of synthesized OxyS RNAs. Full‐length cDNA (FL). Arrow denotes termination signal. The site of Shine–Dalgarno sequence (GGAG) is denoted in red. Relative intensity (R.I) denotes the ratio of the termination signal per full‐length compared to wild‐type oxyS‐nusG interaction, which was used as a 100% reference.

Source data are available online for this figure.