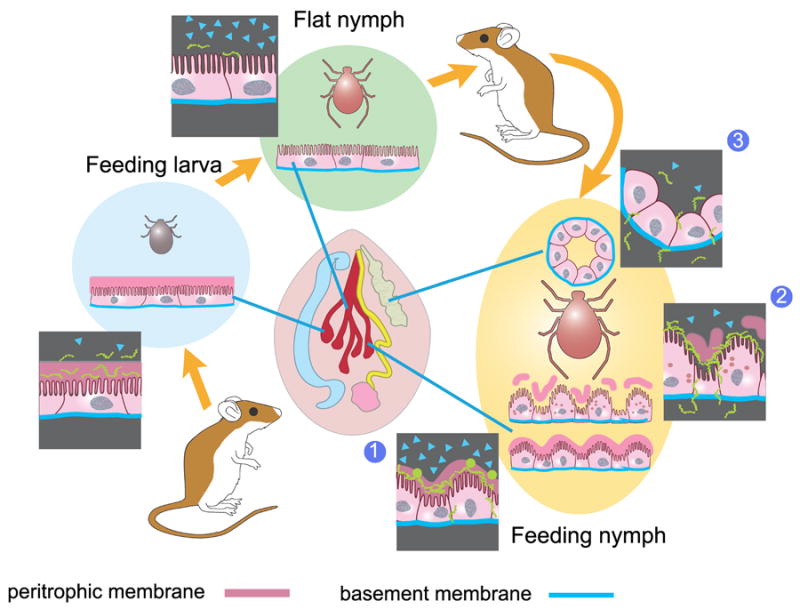

Fig. 2. Hypothetical role of the B. burgdorferi stringent response in the I. scapularis reservoir and vector.

Modulation of bacterial growth mediated by the stringent response is crucial for its adaptation to nutritional challenges. Internal organs of the tick are shown in the central panel (dark red: gut; light green: salivary gland). In feeding larvae during acquisition of spirochetes (light blue circle), rapid growth in the gut (cell layer and magnified inset) results from attenuation of the stringent response within bacterial cells. In flat nymphs (bright green circle)., high levels of (p)ppGpp within the bacteria together with other regulatory molecules stimulate utilization of glycerol and decreased spirochete motility, and appearance of persister cells in the gut lumen via the stringent response. This state continues at the early transmission stage (yellow oval) (1) in the feeding nymph where the stringent response might be involved in spirochete bleb formation, generation of reversible epithelium-associated biofilm-like spirochete networks, round forms and persisters in the gut (cell layers and insets). Later (2), attenuation of the stringent response associated with irruption of blood into the tick gut activates spirochete motility at the basement membrane and migration to the haemocele and the salivary glands (3). Degradation of the peritrophic membrane, produced by enzymes from gut cells and the blood, generates chitobiose, the metabolism of which is derepressed by attenuation of the stringent response and low levels of (p)ppGpp. The shift from glycerol utilization to chitobiose utilization may also be a stimulus for the generation of persister cells. ▲ = (p)ppGpp in borrelia cells