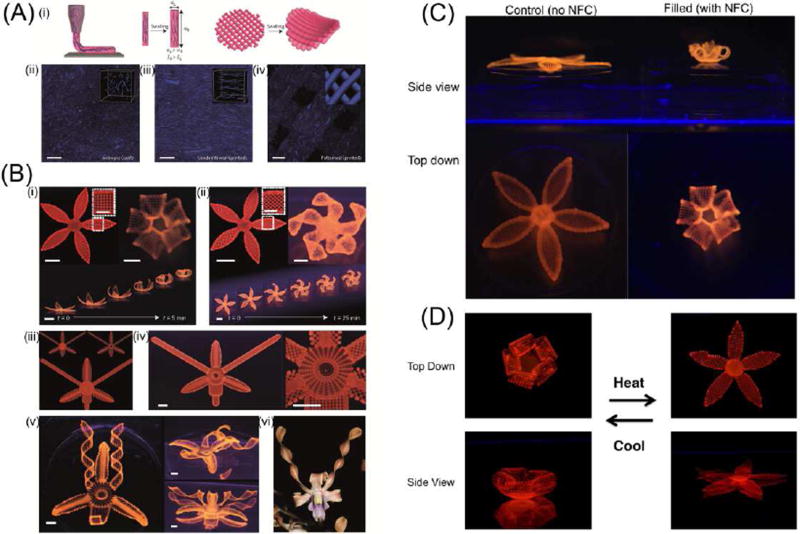

Figure 2.

(A) One-step alignment of cellulose fibrils during hydrogel composite ink printing. (i) Schematic illustration of the shear-induced alignment of cellulose fibrils during direct ink writing and subsequent effects on anisotropic stiffness and swelling strain. (ii–iv) Direct imaging of cellulose fibrils (stained blue) in isotropic (cast) (ii), unidirectional (printed) (iii) and patterned (printed) (iv) samples (scale bar, 200 µm). (B) Complex flower morphologies generated by biomimetic 4D printing. (C) Controlled flower architecture composed of hydrogel ink with 0 wt% (left), compared to flower architecture (right) with 0.8 wt% nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC). (D) Thermoreversible shape change of a flower composed of a poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) hydrogel matrix with 0.8 wt% NFC. Adapted with permission from [2].