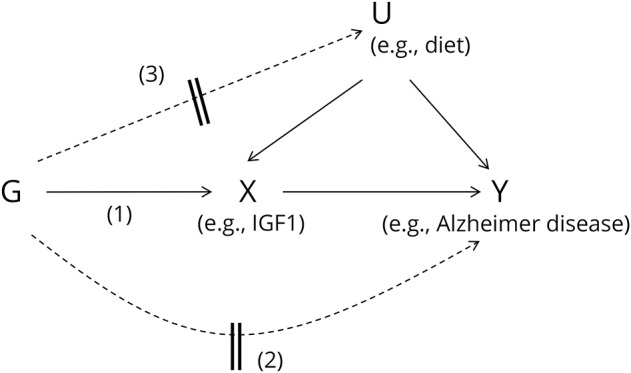

Figure 1. Directed acyclic graph illustrates the mendelian randomization approach.

Observational studies may have established an association between an exposure (X), such as variation in insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), and outcome (Y), such as risk of Alzheimer disease. These studies will be biased from confounding (U) of the X–Y association that is unmeasured/uncontrolled by statistical models, and possibly other sources of bias such as reverse causation. Mendelian randomization can help to assess whether the exposure is causally related to outcome by using a genetic variant (G) (or several in combination) as an instrumental variable for an exposure. This assumes that the genotypes are robust determinants of the exposure (pathway 1). Due to the independent assortment of alleles for variants between parents and offspring at conception, genotypes that determine the exposure should not also determine confounding factors, nor should disease status modify the genotype (reverse causation).13 Therefore, G–Y associations should help to infer a causal relationship of X with Y if instrumental variable assumptions hold. There are potential violations to the framework that can induce direct association of genotypes with outcome independently of the exposure and confounders (pathway 2), or indirectly via confounders (pathway 3). For example, these could arise from horizontal pleiotropy (variants having multiple effects that are independent of exposure determination), linkage disequilibrium between the instrumenting variants and others that affect other traits, or population stratification leading to clustering of variant genotypes and confounding traits.