Abstract

Context:

Palliative care has not developed widely in rural North India. Since 2010, the Emmanuel Hospitals Association (EHA) has been developing a model of palliative care appropriate for this setting, based on teams undertaking home visits with the backup of outpatient and inpatient services. A project to further develop the model operated from 2012 to 2015 supported by funding from the UK.

Aims:

This study aims to evaluate the EHA palliative care project.

Settings and Design:

Rapid evaluation method using a mixed method realist approach at the five project hospital sites.

Methods:

An overview of the project was obtained by analyzing project documents and key informant interviews. Questionnaire data from each hospital were collected, followed by interviews with staff, patients, and relatives and observations of home visits and other activities at each site.

Analysis:

Descriptive analysis of quantitative and thematic analysis of qualitative data was undertaken. Each site was measured against the Indian Minimum Standards Tool for Palliative Care (IMSTPC).

Results:

Each team followed the EHA model, with local modifications. Services were nurse led with medical support. Eighty percent of patients had cancer. Staff demonstrated good palliative care skills and patients and families appreciated the care. Most essential IMSTPC markers were achieved but morphine licenses were available to only two teams. Remarkable synergy was emerging between palliative care and community health. Hospitals planned to fund palliative care through income from surgical services.

Conclusions:

Excellent palliative care appropriate for rural north India is delivered through the EHA model. It could be extended to other similar sites.

Keywords: Community health, palliative care, program evaluation, rural healthcare

INTRODUCTION

While palliative care has been developing in India over the last 30 years only about 1% of the population receive the palliative care they need.[1] Development has been patchy with services being concentrated in South India or in larger cities in the north,[2] with almost no provision for the vast numbers of people in rural North India.

An innovative community-based model for the development of palliative care is starting to emerge in rural North India through the pioneering work of Emmanuel Hospitals Association (EHA), a network of 20 independent Christian mission hospitals.[3] The development started at Harriet Benson Memorial Hospital (HBMH) in Lalitpur, in the south of Uttar Pradesh in 2010 following a district-wide needs assessment. This demonstrated a high level of need for palliative care in the community, with many people with advanced illness effectively sequestered within their homes, receiving little, if any health care and living in extreme poverty. Often the family had fallen into debt securing medical treatment earlier in the disease process.

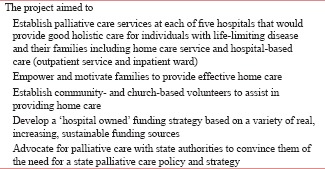

Funding from EMMS International (EMMSI), a health-care development organization, based in Scotland, enabled a 3-year project to be undertaken (2012–2015) focusing specifically on further developing and testing of the HBMH palliative care model [Box 1].

Box 1.

Aims of the Emmanuel Hospitals Association/EMMSI project - 2012-2015

Three hospitals in Uttar Pradesh, one in Madhya Pradesh, and the other in Maharashtra were selected to take part. Three started the project in 2012, one in 2013, and one in 2014. Each hospital made minor variations to the overall model so that they could build on their local contextual resources.

A final evaluation of the project was undertaken in March–April 2015, which aimed to establish whether EHA and the hospitals had achieved their aims, to explore what had been learned and to identify the facilitators and barriers to making the model successful.

METHODS

The evaluation followed a rapid evaluation method an appropriate approach to assessing the impact of rural health-care interventions.[4] A realist approach using mixed methods allowed for quantitative and qualitative data to be integrated,[5] enabling a rich insight into the context and mechanisms which led to the success or otherwise of the intervention in each setting to emerge.[6] Data collection included

Analysis of documentary evidence provided by EMMS, EHA, and other mentor organizations

Standard questionnaire sent to each site to collect activity data

Key informant interviews with two EHA project leaders to explore the overall functioning of the project

-

Site visits to the five hospitals involved with the project which included:

- 32 interviews with palliative care staff and other senior staff, including hospitals management at each site

- Observational data collected including team meetings and community visits

- 12 interviews with patients and carers.

Elements 1–3 were conducted before site visits and guided subsequent data collection. Data from the documentary analysis were summarized and analyzed. Questionnaire data were analyzed using descriptive statistics with Microsoft Excel. Interview data were recorded by taking extensive notes during interviews and by audio recording. Observational data were recorded in the evaluators’ field notes. Both interview and observational data were analyzed thematically, and themes were compared and integrated.

Finally, assessment of the results for each hospital was made against the Indian Minimum Standard Tool for Palliative Care (IMSTPC)[7] and evaluation of the whole project was made with reference to the WHO palliative care public health criteria.[8]

RESULTS

The characteristics of the palliative care teams

All five sites had established a palliative care team which focused on delivery of palliative care in the surrounding community with regular home visits. All teams had 2–5 dedicated and permanent nursing staff, including both nurses and nursing care assistants, with leadership support from a hospital-based GNM nurse who had received some training in palliative care. The teams had medical support from hospital physicians in three sites and dentists in two. All teams had daily meetings as well as a weekly planning meeting with the doctor/dentist attending. In one site, a dentist was part of the visiting team, and in three others, a medical/dental practitioner was able to undertake visits at the nurses’ request. At site 2 patients had to attend the general outpatients’ clinic to receive medical input which could lead to delay in medical assessment. Each team had reflective meetings discussing patients and the care provided, with one demonstrating exceptionally good teamwork.

All team members had received education in palliative care on the 10 day Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) course run by EHA, which provided training twice per year (this was the only IAPC course in rural north India). Some team members had received more extensive training. The doctor at site 1 was undertaking a diploma in palliative medicine and at site 3 had undertaken a 6-week course. Two nurses in site 2 had undertaken a month-long course. All teams used the ‘Help the Hospices Toolkit’ for palliative care as a resource[9] and a variety of other texts.

All of the teams were developing knowledge and skills building on their basic palliative care education. Detailed clinical reports were sent each week to the project lead, a palliative care physician in Delhi, who also paid regular visits to each site monitoring their clinical work and provided ongoing support and education. Four sites had also received mentor visits from the UK benefitting both clinically and in developing service strategy.

Palliative care delivery

In each hospital, patients were triaged according to their needs. Each patient was followed up at least once every 4 weeks, others every 2 weeks, and occasionally weekly if needed. Families were given the mobile number of the palliative care team to call if problems arose between visits and this was frequently used. At each site, 80% of the patients had cancer apart from site 5 which was in areas with high levels of HIV. Visits occurred 5 days a week with planning meetings on Saturdays. The number of daily visits varied because of the distances travelled and poor roads.

Assessment, nursing care and symptom control

All teams demonstrated good listening and consultation skills and were able to elicit physical symptoms, prescribe appropriate medication, and provided excellent practical nursing care. They taught families basic nursing skills such as bathing, wound dressings, and administration of medication and gave advise on nutrition.

"Without the medicine and cleaning the wound, he would be in much more pain and much more uncomfortable" (Wife of a patient)

Psychological and spiritual support seemed more superficial, probably because of relative lack of training and experience in these areas. However, it was evident that the overall presence and attention from the team provided huge emotional comfort both for the patients and their family.

"Because of the team we are able to keep our courage, her worries go away when she sees (the team)." (Husband of a patient).

Building trust and relationships in the community

It was evident that teams needed to work on building trust and relationships in the local community.

"It can be difficult as the patients feel they have been cheated by lots of people, so it can take a lot of time and energy to gain their trust. It gets easier to gain trust from new patients as we build up the service; information is spreading around the villages about the service" (Nurse).

It was apparent that cultural differences and sometimes language difficulties could be a challenge for the teams.

"We are only just starting to understand some of the [local] rituals. We found that if you tell people that the patient is dying, they will put them on the floor– now we don’t tell people they are dying." (EHA doctor).

The nurses and doctors of the palliative care team were mostly not local to the communities in which they worked and relied on the nursing assistants and drivers to assist them in understanding local customs.

"I can help build the trust between the patients and the nurses as I am local and I know how to speak to the people" (community driver).

It was evident that the teams had built positive relationship with members within the community.

"I found it very helpful that the team taught me to care for my friend in a better way. Without the team, the situation would have been so much worse" (friend of patients who had died).

Others in the community also expressed a very positive attitude toward the work that was being done.

"Once when the team arrived in a village it was heard said. ‘Oh, the people who serve us have come’ ". (Doctor).

Conversely, this doctor also reported how they could face opposition within the community particularly from local people who were suspicious and could not accept that the palliative care service was there to serve and did not have an ulterior motive.

Awareness raising

Awareness raising in the community was a key feature in identifying and reaching patients in need of palliative care and was a central aspect of the work in each site. However, it varied in focus and demonstrated how each site built on local resources and opportunities. Site 1 frequently held village meetings, and this was the common way for patient identification to occur. Site 2 worked with local Ayurvedic practitioners who would identify patients for the team. In site 5, staff described how awareness building in local schools was particularly effective with teachers often able to identify families with people who could benefit from palliative care services. Site 4, in an area with a large Muslim community, were developing links with the local mosques. Site 3 had used a local radio station to publicize their service and was developing links with oncologists in the nearest city where many patients with cancer were managed. At this site, most referrals came from the hospital outpatient clinic or by word of mouth from people in the community who were aware of the service.

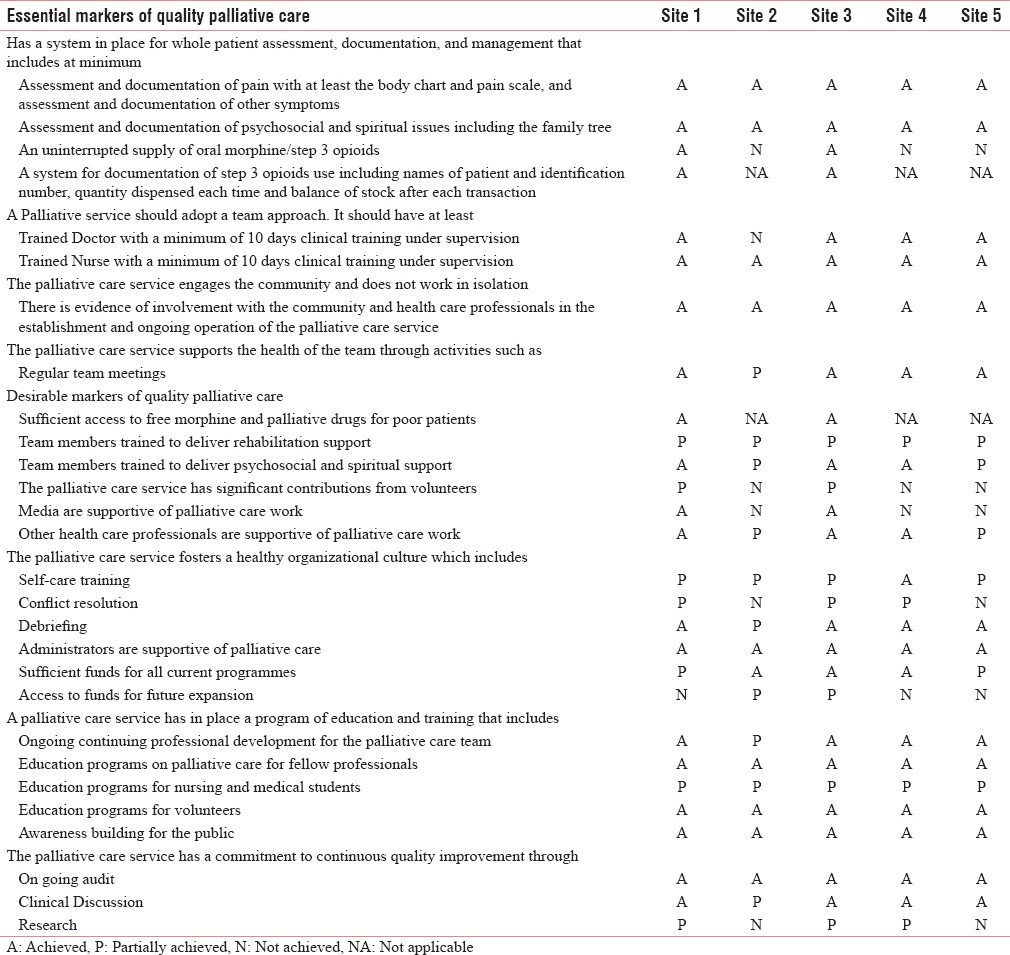

Measurement against Indian minimum standard tool for palliative care [Table 1]

Table 1.

Adapted Indian minimum standards tool for palliative care

Site 1 and site 3 achieved all of the essential markers of the minimum standards [Table 1]. Site 4 did not achieve all of the essential markers because at the time of our visit, they did not have an uninterrupted supply of morphine, although they were confident that they would achieve this soon (and in fact did so within 2 months of our visit). Site 5 also did not achieve this marker because of very challenging conditions (see below). Site 2 was the only site not achieving two essential standards as they did not have morphine available nor did they have a palliative care trained doctor/dentist. In addition, each site achieved the majority of the desirable markers.

Morphine availability

The two sites with morphine availability and the one achieving it later were in Uttar Pradesh. Site 2, in Madhya Pradesh, was a large established hospital providing a range of high-quality services which was well staffed medically. However, they did not receive the support of the District Medical Officer for a morphine license because he believed that to prescribe morphine safely they needed an oncologist on the hospital staff. Site 5 in Maharashtra was unable to obtain a morphine license because they needed an anesthetist to fulfill State regulations.

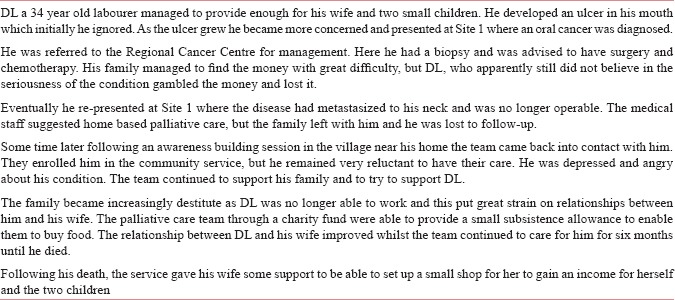

Financial support

Patients and families were often extremely poor [Box 2]. At each site, people assessed as "below the poverty line" were entitled to financial support from the "Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana" (RSBY) government health insurance, from which one household can receive 30,000 INR of hospital medical care per year. Many poor families, however, were marginalized because of their low caste and were not able to access the scheme. This was also true for "Rashtriya Arogya Nidhi" from which the poor can receive up to 100,000 INR of cancer treatment at a Regional Cancer Centre. Part of the support which the teams offered, was to accompany patients to government offices so that they could be processed and receive their entitlement.

Box 2.

Destitute patient's story

The RSBY system allowed patients to access inpatient palliative care at the EHA hospitals, enabling inpatient services to be paid for, rather than payment having to come from the overstretched hospital charity funds.

Community engagement-community volunteers

It was evident that family members learned new skills while caring for their relative supported by the teams. There was some indication that after their family member had died; some were prepared to use their skill to be involved in caring for others within their communities. These were early signs of potential community engagement that could be built on suggesting that palliative care could possibly be transformational for communities in this regard.

There was also evidence of synergy between community health services and palliative care. Community health and public health practitioners had been involved in developing the awareness building skills of the palliative care teams, and palliative care could have a positive impact on the effectiveness of community health programs.

"One village where people had closed their doors [to health education]– they did not want to know, when we went again after starting palliative care they gave the staff a hug and became open to community health." (nurse leader at site 2).

This however was only able to happen where palliative care services and community health projects served the same areas, which only happened at two of the sites

Palliative care had had an impact on the pastors (church leaders) working with the hospitals. Several of these had developed an understanding that palliative care was a way in which the Christian community could serve the poor and disadvantaged in society. Several in the palliative care teams believed that this would, in time, have a fuller impact on the communities.

Sustainability of service

The major threat for many of the sites was lack of funding because none could generate income directly from palliative care services. The management at each site told us that they were committed to continuing the service even if external funding was no longer available. Site 2, 3, and 4 were able to generate additional income from surgical services and could continue the palliative care service from these funds. At site 5, the dental intern was planning on setting up a dental service, and an X-ray machine had been purchased to generate income although we were unclear whether they could generate sufficient funds by these means.

The project lead from EHA took a very active role in supporting each hospital, but as the services grew if was clear that this was not sustainable in the long term. However, the teams were developing their skills and becoming more self-reliant.

DISCUSSION

All teams, even at an early stage in their development, were delivering effective palliative care achieving most of the essential IMSTPC standards,[7] the main exception being the failure to procure an uninterrupted supply of morphine. Morphine supply is known to be problematic in India, due to the Narcotic Drug and Psychotropic Substance Act NDPS (1985), which led to cumbersome regulation introduced by state governments.[10] Amendment of the NDPS in 2014 established a national process which should make the system less cumbersome. In 2015, many states had not changed their systems, and where they had, institutions still needed to commit considerable resources and time to see the benefits.[11] The sites which had established a morphine supply were all in Uttar Pradesh, and two of them had been able to build on the achievement of site 1. The sites were also achieving the majority of the desirable IMSTPC markers, and there was evidence that over time and with further training more of these could be met. An important aspect of this development seemed to be the visit of mentors who could spend time with the teams enabling them to develop their clinical, professional and organizational skills. Mentors have been effective in enabling service development in other low- and middle-income countries[12] and training and development for mentors is available.[13]

The project showed innovative task shifting.[14] In two of the sites, dentists were used to provide medical support. While there were clearly difficulties because of the limit to the breadth of a dentist's general medical experience, their understanding of pharmacology, particularly of pain control enabled them to effectively support the teams. Drivers acted as advocates with the community where the clinical staff were not local and could also provide support to the mainly female team members. In one site, the driver had been taught to perform basic clinical tasks such as dressings.

A major challenge for all sites was the lack of funding for services. The patients and their families were unable to pay for the care they received and so the services needed to be funded in other ways. Use of the RSBY health insurance was helpful in paying for inpatient care, but this is not available for community services and access to it was often challenging.[15] Hospitals which were able to generate income could choose to support palliative care, but there were competing priorities for funding potentially making it difficult to maintain services. In South India, particularly Kerala, palliative care is supported by charity and voluntary donations,[16] however, this seems particularly challenging in rural North India because of the high levels of poverty in rural communities.

All of the sites were only able to provide palliative care within a 40 km radius of the hospital. Given the vast rural areas in North India, even though EHA have developed a successful model for providing palliative care and meeting the WHO criteria,[8] the majority of people living in these states are still unable to access palliative care near their homes. Many similar services would need to be established to enable universal coverage and a public health approach to providing palliative care.

India signed the 2014 WHA agreement to incorporate palliative care into its health-care system enabling universal access to palliative care.[17] The government of India has also committed to "universal access to good quality health care services without anyone having to face financial hardship as a consequence."[18] Incorporating palliative care into services at the district level as part of universal health coverage is arguably a way of achieving both of these commitments. There is evidence that palliative care can be poverty reducing[19] and providing people with the option for palliative care close to home could prevent people from trying to access futile and expensive treatment at a late stage which puts them and their families into increasing poverty.

While this is a huge challenge, the EHA model could form the basis of providing cost-effective palliative care in rural north India. The model relies on home visits as patients tend to be sequestered in their homes, but there is evidence that palliative care can be transformational within communities. Organizing services on a district level could facilitate population-wide service provision.

CONCLUSION

EHA has developed a model of successfully providing palliative care to rural areas of North India. This relies on mobile community teams with the support of hospital inpatient and outpatient services. The model could be scalable to allow universal coverage of palliative care in rural areas to emerge if institutions such as government district hospitals provided similar palliative care services.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajagopal M. The current status of palliative care in India. Cancer Control. 2015:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDermott E, Selman L, Wright M, Clark D. Hospice and palliative care development in India: A multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:583–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EHA. The Emmanuel Hospitals Association. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.eha-health.org/about-us .

- 4.Anker M, Guidotti RJ, Orzeszyna S, Sapirie SA, Thuriaux MC. Rapid evaluation methods (REM) of health services performance: Methodological observations. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson C. 3rd ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 2011. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borglin G. The value of mixed methods for reserching complex interventions. In: Richards DA, Hallberg I, editors. Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajagopal M, Joad AK, Muckaden M, George R, Gupta H, Leng ME, et al. Creation of minimum standard tool for palliative care in India and self-evaluation of palliative care programs using it. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20:201–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.138395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pains Symptom Manage. 2007;33:486–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bond C, Lavy V, Wooldridge R. London: Help Hospital; 2008. Palliative Care Toolkit: Improving Care from the Roots Up in Resource-Limited Settings. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallath N, Tandon T, Pastrana T, Lohman D, Husain SA, Cleary J, et al. Civil society-driven drug policy reform for health and human welfare-India. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:518–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosla D, Patel FD, Sharma SC. Palliative care in India: Current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:149–54. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.105683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant L, Brown J, Leng M, Bettega N, Murray SA. Palliative care making a difference in rural Uganda, Kenya and Malawi: Three rapid evaluation field studies. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logie D, Grant L, Leng M. Mentoring palliative care staff in low-income countries has benefits for all. Eur J Palliat Care. 2011;18:235–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi R, Alim M, Kengne AP, Jan S, Maulik PK, Peiris D, et al. Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries – A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta S. Awareness and utilization of Rashtriya Swasthaya Bima Yojana and its implications for access to health care by the poor in slum areas of Delhi. Health Syst. 2017;6:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallnow L, Kumar S, Numpeli M. Home-based palliative care in Kerala, India: The neighbourhood network in palliat care. Prog Palliat Care. 2010;18:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geneva: WHO; 2014. WHA. Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Comprehensive Care Throughout the Life Course. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathur MR, Reddy KS, Millett C. Will India's national health policy deliver universal health coverage? BMJ. 2015;350:h2912. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratcliff C, Thyle A, Duomai S, Manak M. Poverty reduction in India through palliative care: A pilot project. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:41–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.197943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]