Abstract

Introduction:

Cancer wounds need regular dressing; else they develop infection, foul odor, and in extreme cases, maggots. Patients resist dressing due to the severe incidental pain during dressing. Intranasal ketamine was tried as an analgesic to reduce this incidental pain.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty patients with wounds requiring regular dressing were selected; these patients had a basal pain score of 4/10 and incidental pain score of 7/10 during four consecutive dressings. Ketamine 0.5 mg/kg was administered transmucosally 10 min before dressing, and pain scores, hemodynamic parameters, and sedation were recorded for up to 2 h in six consecutive dressings.

Results:

Ketamine produced a significant reduction in incidental pain without any hemodynamic changes or sedation.

Conclusion:

Ketamine appears to be a safe and effective analgesic when used intranasally for incidental pain.

Keywords: Cancer pain, incidental pain, ketamine, pain management, wound dressing

INTRODUCTION

The neurophysiology of pain is complex,[1] in cancer even more so, hence challenging.[2] Inflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and psychological components are present in varying amounts, all at once.[3]

In patients with open wounds, cleaning and dressing of the wound present an ordeal by triggering incidental pain. Incidental pain is a complex entity, which involves inflammatory pain due to mechanical stimulation of raw areas, severe neuropathic pain due to exposed free nerve endings, nociceptive pain due to tissue manipulation, and a huge psychological component due to the wound.[4] In wound management, cleaning and dressing changes are essential.[5] Lack of patient cooperation, due to the agony during dressing, leads to inadequate cleaning and the consequent development of infection, foul-smelling discharge, maggots, etc.[6] Furthermore, repeating such a painful procedure up to twice a day reduces the patient's quality of life. Since pain has an adverse impact on patients and their families, optimal management of pain should be a priority for all clinicians.[7] In the same way, pain should be aggressively managed even during dressing.

Conventionally, several methods have been tried to alleviate incidental pain including parenteral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and breakthrough doses of morphine but without satisfactory results. Ketamine, a phencyclidine derivative, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, which has an ideal pharmacokinetic profile for procedural analgesia. It has a rapid onset of action (30–40 s after intravenous (iv) administration and 7–9 min after buccal administration), prolonged and profound analgesic action, minimal or no respiratory depression, and no effect of renal impairment on excretion.[8,9]

Considering the efficacy of ketamine for burn dressings[10] and the striking resemblance between cancer wounds and burn wounds, an open-label, uncontrolled pilot study was designed to confirm the efficacy and safety of intranasal ketamine on incidental pain during dressing in oral cancer patients. During the study, pain and its suppression were measured by visual analog scale (VAS) as was the cardiovascular response and sedation if any, produced.

Aims and objectives

To study the efficacy of transmucosal ketamine in reducing incidental pain during dressing in oral cancer patients

To study the effect of ketamine on hemodynamic parameters

To assess the sedative effect of ketamine

To assess the adverse effects of ketamine, if any.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted on twenty oral cancer patients admitted to Cipla Palliative Care and Training Center. Patients with wounds requiring dressing were chosen for the study. Recruitment began after approval of the protocol by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Before recruitment, a written informed consent form was signed by the patients and caregiver.

Inclusion criteria

Oral cancer patients with a life expectancy exceeding 1 month, having an open wound that requires dressing

Age - 18–60 years

Gender - male or female

Patients with stable pain (VAS < 4/10, on oral morphine)

Patients with pain score >7/10 during four previous dressings

Patients signing an informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with distant metastases

Patients with raised intracranial tension

Patients in renal/hepatic failure

Unresponsive patients

Patients with uncontrolled pain

Patients with hypertension

Patients in delirium

Patients with psychiatric illness/drug abuse (including alcohol)

Patients received 0.5 mg/kg of ketamine (as a 50 mg/ml solution) administered nasally as drops administered by a syringe 10 min before dressing. Pain score was measured using the VAS; pulse and blood pressure were assessed at the beginning of dressing and every 5 min during dressing. Monitoring continued every 30 min thereafter, until 2 h. Sedation was assessed every 15 min for 2 h, according to the Ramsay sedation score.[11] Emergence reactions and other adverse events were looked for up to 12 h. The average pain score over six dressings in each patient was noted, and this was used for calculations.

The results were tabulated and analyzed.

RESULTS

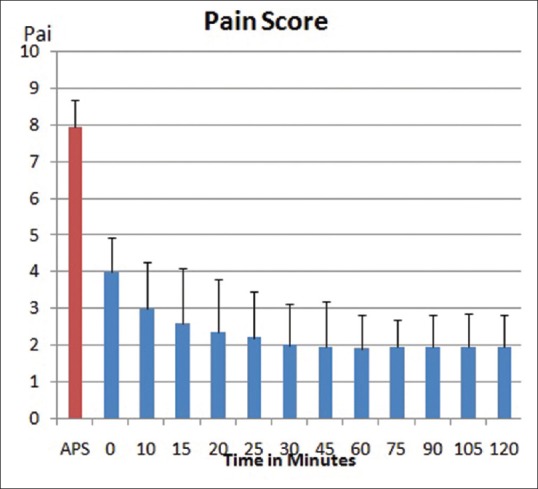

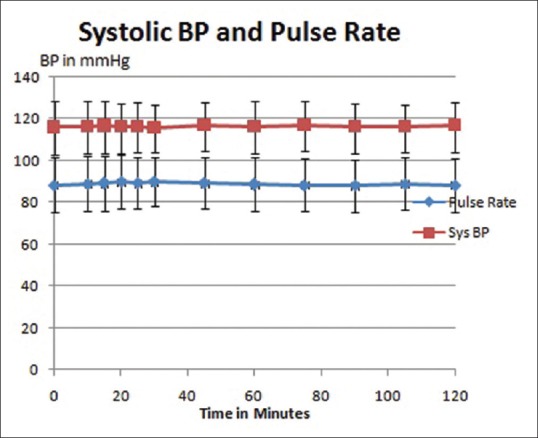

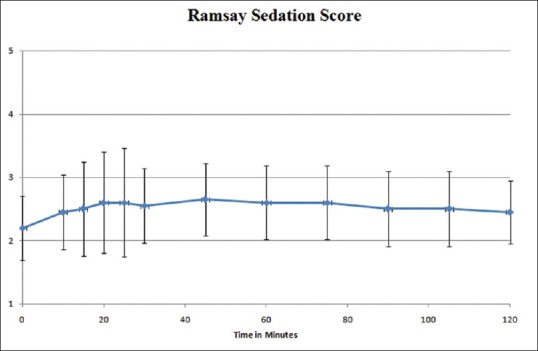

Patients who had a baseline pain score ≥4, but incidental pain score during dressing ≥7 were chosen for the study. In the four previous dressings (without the use of ketamine), mean incidental pain was VAS 7.95 ± 0.74 as shown in Figure 1. After administration of ketamine, mean pain score during dressing was 2.98 ± 1.1. Mean pain score after 1 h was 1.9 ± 0.94 and at 2 h mean pain score was 1.95 ± 0.86. The pain scores after ketamine were significantly lower than those before ketamine (P < 0.0001). There were no changes in the blood pressure and pulse rate, nor was there any sedation as measured by the Ramsay Sedation Scale, these results are graphically represented in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Pain score reduction on the use of intranasal ketamine

Figure 2.

Stable hemodynamic parameters

Figure 3.

Improved Ramsay sedation score without excessive drowsiness

DISCUSSION

Ketamine has been conventionally used in burn dressings, especially in patients with >20% burns.[12] Just like cancer wounds, burn wounds are extensive, requiring multiple dressing changes, extremely painful, with multiple etiopathogeneses for the pain, leading to the development of tolerance to opioids.[13]

Advantages of ketamine include multiple routes of administration, maintenance of airway tone, relaxation of bronchial smooth muscles, and increased sympathetic tone, apart from excellent analgesia.[14] Ketamine has a pharmacokinetic profile that makes it an ideal agent for procedural analgesia. It has a rapid onset of action (30–40 s after iv administration and 7–9 min after buccal administration), prolonged and profound analgesic action, minimal or no respiratory depression, and no effect of renal impairment on excretion.[15] The transmucosal route is easy to administer, provides faster onset, and precludes the need for injections.[16] The nasal transmucosal route eliminates the bitter taste experienced by the patient when given buccal mucosally. Use of ketamine led to approximately a 63% reduction in the incidental pain during dressing, and the analgesia was sustained for up to 2 h.

Adverse effects associated with the administration of ketamine in adult patients include hypertension, tachycardia, emergence reactions, and skeletal muscle hyperactivity. Other common side effects include increased upper airway secretions, nystagmus, and diplopia;[17,18] however, none of these were observed in the present series. Out of the twenty patients we studied, one patient experienced dysphoria and opted out of the study.

CONCLUSION

Transmucosal ketamine is a safe and effective method to alleviate incidental pain during dressing in cancer patients. Its regular use for dressing and other procedures done on cancer patients will greatly help in improving the quality of life.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguggia M. Neurophysiology of pain. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(Suppl 2):S57–60. doi: 10.1007/s100720300042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamai N, Mugita Y, Ikeda M, Sanada H. The relationship between malignant wound status and pain in breast cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;24:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twycross R. Cancer pain classification. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:141–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ripamonti CI, Bossi P, Santini D, Fallon M. Pain related to cancer treatments and diagnostic procedures: A no man's land? Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1097–106. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilley C, Lipson J, Ramos M. Palliative wound care for malignant fungating wounds: Holistic considerations at end-of-life. Nurs Clin North Am. 2016;51:513–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seaman S. Management of malignant fungating wounds in advanced cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2006;22:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo SF, Hayter M, Hu WY, Tai CY, Hsu MY, Li YF, et al. Symptom burden and quality of life in patients with malignant fungating wounds. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:1312–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mion G, Villevieille T. Ketamine pharmacology: An update (pharmacodynamics and molecular aspects, recent findings) CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013;19:370–80. doi: 10.1111/cns.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peltoniemi MA, Hagelberg NM, Olkkola KT, Saari TI. Ketamine: A Review of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in anesthesia and pain therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016;55:1059–77. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: Current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8:283–90. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.143110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deol H, Minaie A, Surani S, Udeani G. Reliability and utility of the Ramsay sedation scale for dosing sedatives in critically ill intubated patients. Chest. 2017;151:143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuinness SK, Wasiak J, Cleland H, Symons J, Hogan L, Hucker T, et al. A systematic review of ketamine as an analgesic agent in adult burn injuries. Pain Med. 2011;12:1551–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowan MP, Cancio LC, Elster EA, Burmeister DM, Rose LF, Natesan S, et al. Burn wound healing and treatment: Review and advancements. Crit Care. 2015;19:243. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0961-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caddy C, Giaroli G, White TP, Shergill SS, Tracy DK. Ketamine as the prototype glutamatergic antidepressant: Pharmacodynamic actions, and a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4:75–99. doi: 10.1177/2045125313507739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell RF, Kalso E. Is intranasal ketamine an appropriate treatment for chronic non-cancer breakthrough pain? Pain. 2004;108:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen L, Marshalek PJ, Weaver CB, Cramer KJ, Pollard SE, Matsumoto RR, et al. Off-label use of transmucosal ketamine as a rapid-acting antidepressant: A retrospective chart review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2667–73. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S88569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strayer RJ, Nelson LS. Adverse events associated with ketamine for procedural sedation in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:985–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niesters M, Martini C, Dahan A. Ketamine for chronic pain: Risks and benefits. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:357–67. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]