Abstract

This study characterizes trends in the use by nursing homes of nursing home specialists (defined as generalist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) who billed at least 90% of their clinical episodes from nursing home settings between 2012 ans 2015.

Nursing home care is common, costly, and variable in quality. For instance, between September 2009 and August 2010, 23% of the 1.5 million hospital discharges to post–acute care in nursing homes resulted in rehospitalization or death within 30 days, with variation across facilities. One approach adopted by hospitals to improve care over the past decade was to concentrate it among physicians who specialize in treating hospitalized patients (hospitalists). Our goal was to determine whether nursing homes are adopting this strategy by measuring the prevalence of “nursing home specialists” between 2012 and 2015.

Methods

The University of Pennsylvania institutional review board waived review of this study. We used the Provider Utilization Files, containing all Part B Medicare fee-for-service billings, to identify generalist physicians (internal medicine, geriatrics, general practice, or family medicine) and advanced practitioners (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) who provided nursing home–based care (Health Common Procedure Coding System codes, 99304-99310, 99315-99316, or 99318) from 2012 through 2015. We aggregated episodes of care by clinician to measure the proportion of episodes that were nursing home–based. We then defined clinicians who billed at least 90% of episodes from the nursing home as nursing home specialists (a definition analogous to the one used to identify hospitalists). We also subcategorized nursing home–based episodes into post–acute care vs long-term care episodes using place of service codes.

To account for nursing home bed availability and use, we used the Long-Term Care Focus database to calculate the mean number of occupied Medicare-certified beds per year in each hospital referral region (HRR). The number of clinicians was aggregated at the HRR level based on their billing zip code and reported per 1000 occupied Medicare-certified beds.

We excluded clinicians with fewer than 100 episodes of care per year and those from 1 HRR (Alaska) with missing occupancy data.

Linear regression was used to model the number of clinicians (or clinicians per 1000 occupied nursing home beds) in each HRR as a function of year. Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp), version 13.1.

Results

Among 319 264 unique generalist clinicians, 50 227 (15.7%) billed for nursing home care from 2012 through 2015. The number of clinicians billing for nursing home care remained relatively stable (−0.4%; from 33 218 to 33 087; P for trend, .97) (Table), whereas the total number of generalists increased (15.6%; from 224 358 to 259 373; P for trend, <.001). The number of nursing home specialists increased from 5127 to 6857 (P for trend, <.001), a relative increase of 33.7%. The mean number of nursing home specialists per 1000 beds increased from 3.35 (95% CI, 3.06 to 3.64) in 2012 to 4.58 (95% CI, 4.19 to 4.96) in 2015 (P for trend, <.001). Clinicians who specialized in post–acute care (2.00 clinicians/1000 beds [95% CI, 1.75 to 2.26]) and advanced practitioners (3.21 clinicians/1000 beds [95% CI, 2.90 to 3.51]) were the most prevalent types of nursing home specialists.

Table. Nursing Home Clinicians Per 1000 Medicare-Certified, Occupied Beds by Clinician Type and Place of Service.

| Year of Part B Medicare Fee-for-Service Billing | P Value for Trenda | Relative Percent Change, 2012-2015b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||

| Nursing home clinicians, No. | 33 218 | 33 316 | 33 357 | 33 087 | .97 | −0.4 |

| Nonspecialist | 28 091 | 27 608 | 27 002 | 26 230 | .39 | −6.6 |

| Nursing home specialist | 5127 | 5708 | 6355 | 6857 | .009 | 33.7 |

| Nursing home clinicians per 1000 occupied beds, mean (95% CI) | 24.70 (23.82 to 25.58) |

24.90 (23.96 to 25.84) |

24.93 (23.97 to 25.90) |

24.99 (24.01 to 25.97) |

.68 | 1.2 |

| Nonspecialist | 21.35 (20.55 to 22.16) |

21.15 (20.29 to 22.00) |

20.70 (19.85 to 21.55) |

20.41 (19.56 to 21.26) |

.09 | −4.4 |

| Nursing home specialist | 3.35 (3.06 to 3.64) |

3.76 (3.45 to 4.06) |

4.23 (3.89 to 4.58) |

4.58 (4.19 to 4.96) |

<.001 | 36.7 |

| Nursing Home Specialists per 1000 Occupied Beds, Mean (95% CI) | ||||||

| Clinician type | ||||||

| Physician | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.23) |

1.22 (1.09 to 1.34) |

1.31 (1.17 to 1.45) |

1.37 (1.23 to 1.51) |

.004 | 23.4 |

| Advanced practitioner | 2.24 (2.02 to 2.46) |

2.54 (2.30 to 2.78) |

2.92 (2.64 to 3.20) |

3.21 (2.90 to 3.51) |

<.001 | 43.3 |

| Place of service | ||||||

| Post–acute care | 1.47 (1.29 to 1.64) |

1.68 (1.49 to 1.86) |

1.85 (1.61 to 2.08) |

2.00 (1.75 to 2.26) |

<.001 | 36.1 |

| Long-term care | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.83) |

0.81 (0.70 to 0.91) |

0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) |

0.90 (0.79 to 1.01) |

.007 | 23.3 |

| Post–acute care and long-term care | 1.16 (1.01 to 1.30) |

1.27 (1.11 to 1.43) |

1.46 (1.29 to 1.63) |

1.67 (1.48 to 1.86) |

<.001 | 44.0 |

To test for statistical significance of the trends, linear regression was used to model the number of clinicians (or the number of clinicians per 1000 occupied nursing home beds) in each hospital referral region (n = 305) as a function of year.

Relative percent change in the number of clinicians per 1000 occupied Medicare-certified beds from 2012 to 2015.

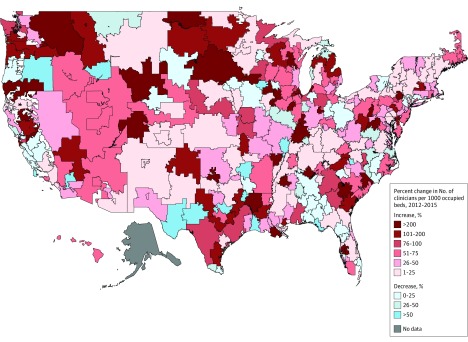

The change in the number of nursing home specialists was uneven across regions: 240 HRRs (78.7%) experienced an increase in nursing home specialists per occupied bed, whereas 61 HRRs (20.0%) experienced a decrease (Figure). The median change across HRRs was a 38.8% increase (interquartile range, 3.8% to 80.7%).

Figure. Relative Percent Change in the Number of Nursing Home Specialists Per 1000 Medicare-Certified, Occupied Beds by Hospital Referral Region, 2012-2015a.

aAdjusted for region occupancy.

Discussion

From 2012 through 2015, the number of clinicians who specialized in nursing home practice increased, whereas the number of generalists who provided any nursing home–based care was stable. The considerable regional variation in the rate of adoption of nursing home specialists may indicate a lack of consensus regarding the benefits of specialization. Limitations stem from coding inaccuracies in billing data and inability to assess care to persons not covered by Medicare fee-for-service.

Despite the large relative increase, nursing home specialists made up only 21% of nursing home clinicians in 2015. Nevertheless, their effect on patient care may be considerable because they provide a disproportionate share of the visits. Whether these changes improve outcomes (eg, through increased access to expert clinicians) or result in adverse consequences (eg, due to worsened care fragmentation) requires ongoing study.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Healthcare Delivery System. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun17_reporttocongress_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed July 27, 2017.

- 2.Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542-1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50 000—the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Research Data Assistance Center Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty (MD-PPAS) user documentation, version 2.2. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/md-ppas/data-documentation. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- 5.Long-Term Care Focus Shaping Long-Term Care in America Project at Brown University funded in part by the National Institute on Aging (1P01AG027296). http://ltcfocus.org. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- 6.Dartmouth Atlas Group Hospital referral region to zip code crosswalk. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/tools/downloads.aspx?tab=39. Accessed July 26, 2017.