Abstract

Heavy drinking in relationships is complex and we focus on an understudied sample of concerned partners (CPs) worried about their U.S. service member/veteran partner’s drinking. We evaluated the link between CP drinking and their own mental health, and how CP drinking moderated the efficacy of a web-based intervention designed to address CPs’ mental health and communication. CPs (N=234) were randomly assigned to intervention or control and completed assessments at baseline and five-months later. CP drinking was associated with greater CP depression, anxiety, and anger independent of partner drinking and the intervention was more efficacious in reducing depression for heavy drinking CPs. CPs are often an overlooked population and resources to help support them are needed.

Keywords: relationships, military, depression, anxiety, anger expression, social control, military spouse, alcohol misuse, web intervention, computer-assisted intervention, CRAFT, spouse or significant other

Heavy drinking adversely affects multiple areas of life for both the heavy drinker and his or her romantic partner. It is well established that spouses and partners of heavy drinkers experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints (Halford, Bouma, Kelly, & Young, 1999; Homish, Leonard, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2006), as well as increased relationship distress and intimate partner violence (Amato & Previti, 2003; Cranford, Floyd, Schulenberg, & Zucker, 2011; Leonard & Jacob, 1988; Leonard & Senchak, 1993; Maisto, McKay, & O’Farrell, 1998; Marshal, 2003). Although previous work has traditionally focused on the effect of one person’s drinking on his or her partner’s well-being, the current research focuses on an underrepresented population of partners of heavy drinking U.S. military service members and veterans who are concerned about their partner’s drinking. First, we focus specifically on how drinking among these concerned partners (CPs) is associated with their own mental health symptoms, responses to their partner’s drinking, and relationship quality. Second, we also test CP drinking as a moderator of the efficacy of a web-based intervention designed to help CPs address their mental health and communication. Thus, this manuscript focuses solely on how CP drinking affects CP outcomes, cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

Concordance and the drinking partnership

Previous work has examined alcohol use in relationships through the lens of interdependence theory (Rodriguez, Neighbors, & Knee, 2014), highlighting that drinkers and partners are interdependent and that each person’s behaviors affect their partner’s outcomes. A discordant drinking pattern, wherein one partner drinks significantly more than the other, is associated with relationship problems, lower martial satisfaction, higher rates of marital difficulty, and higher divorce rates compared to couples with light and/or moderate concordant drinking patterns (Homish & Leonard, 2007; Leadley, Clark, & Caetano, 2000; Mudar, Leonard, & Soltysinski, 2001; Ostermann, Sloan, & Taylor, 2005). Potential explanations for this include: less time spent socializing together; more time spent socializing separately; dissimilarity in leisure activity preference or other values, attitudes, or expectations regarding acceptable behavior in marriage; and one partner’s heavy consumption interfering with their ability to participate in everyday household tasks.

Recently, research has focused on the risk carried by concordant heavy drinking couples, with results from one study showing that concordant heavy drinking couples at baseline were most likely to experience separation and divorce six years later compared with congruent light drinking couples (Wiersma & Fischer, 2014). Similarly, among older couples, the divorce risk of concordant heavy drinkers is higher than that of concordant light drinkers; however, the highest risk occurs when only the wife is a heavy drinker (Torvik, Roysamb, Gustavson, Idstad, & Tambs, 2013; Torvik, Gustavson, Roysamb, & Tambs, 2015). Thus, both discrepant and concordant heavy drinking couples experience greater relationship difficulties and divorce risk than concordant abstaining or light drinking couples.

Unfortunately, studies on the drinking partnership have almost exclusively been limited to general adult community samples. These community samples who do not necessarily share the same concern may manage their behaviors differently than help-seeking partners. Applying a social learning theory (Stuart, 1969; Weiss, Hops, & Patterson, 1973) perspective to this context suggests that CPs communicate their concern in ways that either punish or reward their partner’s drinking (e.g., becoming angry, anxious, withdrawn; Love, Longabaugh, Clifford, Beattie, & Peaslee, 1993), and experience their own consequences as a function of these interactions (e.g., depression, anxiety, reduced relationship quality; Erbes et al., 2012; Rodriguez, DiBello, & Neighbors, 2013). They may punish their partner’s drinking behaviors or find ways to support their partner’s sobriety, but they might also support their partner drinking (perhaps through their own drinking) or withdraw from their partner when their partner is drinking, which may increase conflict (Love et al., 1993). Although all behavioral responses by CPs likely stem from a desire to reduce their partner’s drinking, not all behaviors are equally effective at changing behavior (Rodriguez, 2016). Understanding what CP characteristics affect their own behaviors or moderate these associations is important for tailoring future intervention efforts. For example, CPs may be more receptive to participating in an intervention that helps both themselves and their partners, and may benefit more from dyadic intervention content.

Heavy Drinking among Military Service Members and Veterans

Alcohol misuse is prevalent among military service members. Approximately 40% of married service members in the U.S. report heavy drinking (i.e., occasions of 4+/5+ drinks for women/men, respectively; Paul, Grubaugh, Frueh, Ellis, & Egede, 2011), a rate more than three times that of married civilians (13%; Bray et al., 2009; Karney & Crown, 2007). Moreover, service members and veterans who drink heavily report higher rates of physical and psychological health consequences (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, depression), relationship issues, financial issues, and a greater likelihood of engaging in health-risk behavior (e.g., driving under the influence, risky sex; Bell, Harford, Fuchs, McCarroll, & Schwartz, 2006; Burnett-Ziegler et al., 2011; Foran, Heyman, Slep, & Snarr, 2012; Institute of Medicine, 2012; Williams, Bell, & Amaroso, 2002). Alcohol misuse also creates increased liabilities for the military as it is linked with greater medical and mental healthcare utilization and legal concerns (Bray, Brown, & Williams, 2013; Possemato, Wade, Andersen, & Ouimette, 2010).

Mental health and alcohol use in military spouses

Military spouses and partners (i.e., spouses and partners of service members and veterans) experience taxing stressors associated with military life such as frequent relocation, family separations (e.g., during service member deployments), and worry or anxiety associated with having one’s spouse or partner in harm’s way (Segal, 1986). It is perhaps not surprising that behavioral health issues among military spouses have become increasingly problematic after more than a decade of combat operations and repeat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan (Booth et al., 2007; Eaton et al., 2008). Partners of National Guard members have higher levels of depression and social impairment compared to the service members (Erbes, Meis, Polusny, & Arbisi, 2012), and a heightened domestic violence risk compared to their civilian counterparts (Sayers, Farrow, Ross, & Oslin, 2009). Despite the distress many partners of service members experience, the majority of resources available for military families focus specifically on the service member versus their partner and though intervention efforts have targeted spouses, there are very few research studies specifically evaluating interventions designed for military spouses (Ahmadi & Green, 2011). Thus, focusing on ways to support military CPs are sorely needed.

Little work has examined alcohol use among partners of service members, but the available studies suggest that alcohol and drug abuse among Army spouses has increased (Booth et al., 2007). Because the vast majority of military spouses are women (Booth et al., 2007), much of the research in this area focuses on wives. A recent SAMHSA study (Lipari, Forsyth, Bose, Kroutil, & Lane, 2016) showed that military wives were more likely to binge drink (31.5%) as well as consume alcohol (67.8%) in the past month when compared to all married women (22.7% and 53.8%, respectively). Meanwhile, less than 1% of the military wives received treatment for substance use in the previous year. Though the specific reasons for heavy drinking patterns among military wives have yet to be well examined, one explanation may be that military wives use alcohol as a means of coping with negative affect (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005). As rates of drinking are increasing among military spouses, further research understanding how drinking patterns among CPs are associated with their own mental health would fill significant research gaps in this understudied area and may highlight the need for CP-focused interventions.

Current Research

Drinking among service members and veterans is prevalent and problematic, and although some programs exist (e.g., Osilla, Pedersen, Gore, Trail, & Howard, 2014), options for military CPs are sparse (Ahmadi & Green, 2011). The limited available data on military wives suggests that the increased stress they experience (de Burgh, White, Fear, & Iverson, 2011; Eaton et al., 2008) may place them at an increased risk for developing adverse coping mechanisms such as substance misuse (Figley, 1993). Moreover, although research on wives of service members demonstrates that they experience poorer psychological and relational health, not much research has looked at alcohol use among CPs. Research on alcohol and relationships tends to focus—by default—on the drinking by the heavier drinker and not by the spouse expressing concern. However, examination of drinking among spouses of service members allows for a fruitful avenue of research in understanding links between their own drinking and mental health in this at-risk, help-seeking sample. In this research, we investigate these associations as well as the role of CP drinking in the efficacy of a brief, web-based intervention.

The current research includes two objectives. First, we examine CP mental health, behavioral responses to partner drinking, and relationship quality as a function of how much the CPs drink after controlling for perceived partner drinking. Previous work on the drinking partnership (Roberts & Leonard, 1998; Homish & Leonard, 2007) demonstrates that couples in discordant drinking partnerships evince poorer outcomes such as decreased relationship satisfaction and an increased likelihood of divorce. This study was part of a larger randomized clinical trial focused on evaluating the efficacy of a brief, web-based intervention, Partners Connect, developed to increase the CP’s self-care and positive communication strategies surrounding his or her partner’s drinking ([blinded for review]). Military spouses/partners joined the larger intervention study, irrespective of their own drinking status, because they were concerned about their partner’s drinking; thus, we hypothesize that the lighter drinking CPs would report greater depression, anxiety, and anger expression, as well as lower relationship quality, compared with heavy drinking CPs at baseline. Our second objective was to evaluate whether CP drinking moderated the efficacy of the Partners Connect intervention. Because we expected lighter drinking CPs to experience greater distress at baseline, we hypothesized that the intervention would be more efficacious at improving mental health symptoms and relationship quality for lighter drinking CPs.

METHOD

Participants

A total of 483 CPs were recruited through Facebook and completed a brief online screening survey that assessed for eligibility. Participants were CPs who were required to: (a) be at least 18 years old; (b) be in a romantic relationship with their partner; (c) be living with a post-9/11 service member or veteran partner; (d) not be in the military (i.e., active duty, reserves/guard) currently themselves; (e) have a computer, mobile, phone, or tablet with Internet access; (f) have no plans to separate from their partner in the next 60 days; (g) indicate at least a value of “3” on scale from “1 not at all” to “7 very much” for the degree to which they felt their partner had an alcohol problem; (h) indicate they believed they would be in no danger if their partner found out about their participation in the study; (i) indicate no general concerns they would be physically hurt by their partner; and, (j) be willing to try an online program focused on communicating with their partner about his/her drinking. If they met eligibility criteria, they advanced to an online consent form and a baseline survey.

Of the 483 CPs, a total of 312 CPs were eligible, completed a baseline survey, and then were randomized to either the Partners Connect web-based intervention or a delayed web-based intervention (i.e., control). We removed six of these participants through a series of data verification checks (e.g., partner’s pay-grade and rank did not match; left most of survey blank). Participants (N = 306) were 95% female, an average of 32.1 years old (SD = 6.5), 71% White, 9% Multiracial, 6% African American, 4% Hispanic/Latino, 89% married (M = 7.5 years, SD = 4.9), 77% with kids, and 59% had not attended any college. Of the 306 who completed a baseline survey, 234 completed an online follow-up survey five months post-baseline (76.5%), resulting in 136 intervention and 98 control participants in our final analytic sample.

Procedure

Participants were recruited online through Facebook using methods we have used successfully in other work with military populations (blinded for review). We provided a link to the project website in the advertisements for CPs to find out more information and complete the 10-item online screening survey to assess their eligibility for the study. We used permuted block randomization with random size blocks (Pocock, 1984) to randomly assign CPs to the Partners Connect intervention or the control group (delayed intervention after completing their baseline survey (see [blinded for review], for additional procedure details)). All participants were asked to complete a five-month follow-up survey, after which the control participants were offered the intervention. CPs received $50 for completion of the baseline assessment and $50 for the five-month follow-up assessment. Toward the end of the study, we increased this incentive to $75 for the five-month follow-up if they were hard to reach or if it was close to the end of the 60-day follow-up window (n = 50).

Measures

Own and perceived partner alcohol use

We asked CPs to report on their own and their perceptions of their partner’s alcohol use. Drinking for both themselves and their partner was operationalized by: (a) drinks per week, (b) drinking frequency, and (c) the number of heavy drinking episodes experienced in the past 30 days. First, drinks per week was assessed via the Drinking Norms Rating Form, a modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991). Participants were asked, “Consider a typical week during the past month (30 days). How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), did you drink [or do you think your partner drinks] on each day of a typical week?” CPs provided estimates for the typical number of drinks they and their partner consumed on each day of the week and responses were summed to create scores for CP and for perceived partner drinks per week. Second, drinking frequency was assessed by asking participants, “Think specifically about the past 30 days, up to and including today. How many days did you drink [do you think your partner drank] one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?” CPs indicated a number between 0 and 30 for themselves and for their partner. Finally, the number of heavy drinking episodes was assessed by asking participants, “Considering all types of alcoholic beverages, how many times during the past 30 days did you have 4 or more drinks [do you think your partner had 5 or more drinks] on an occasion?”

Depression

CPs’ depressive symptoms in the previous two weeks were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., 2009). The PHQ-8 is a well validated measure of depression severity in primary care and in the general population. Each of the eight items (e.g., “feeling bad about yourself, or that you are a failure, or have let yourself or your family down”) is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Internal reliability was acceptable in the current sample (α = .84).

Anxiety

CPs’ anxiety symptoms in the previous two weeks were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan, & Lowe, 2007). Example items include “Worrying too much about different things,” and “Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge.” Responses were provided on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) scale. Internal reliability was high (α = .90).

Anger expression

We measured CPs’ anger expression (i.e., anger directed towards other persons or objects; anger directed inward) on the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI-2) (Spielberger, 1999). An anger expression index comprised of four subscales was calculated such that higher index scores indicated more intense anger that is suppressed, expressed aggressively, or both (α = .76). Example items include “I feel like cursing out loud” and “I am a hotheaded person.”

CP behaviors towards partner drinking

The Significant-other Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ) was used to measure CPs behavior towards their partner’s drinking and abstinence (Love et al., 1993). The subscales include five items assessing punishment (e.g., “show how unhappy you are when your partner was drinking”; α = .84), eight items assessing support of sobriety (e.g., “do things your partner likes when he/she was not drinking”; α = .85), three items assessing support of drinking (e.g., “bring alcoholic beverages home”; α = .66), and four items assessing withdrawal from partner’s drinking (e.g., “leave house when your partner drinks”; α = .70). Each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Always/Almost Always.”

Relationship quality

The CPs’ perceptions of the quality of their relationship with their partners was measured using the 6-item Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983; α = .96). Example items include “Our relationship is strong” and “I really feel like part of a team with my partner.” The QMI has been used in previous studies of military couples (Doss et al., 2012).

Analysis Plan

For both aims, our analysis plan included three different indicators of CP drinking: drinks per week, drinking frequency, and number of heavy drinking episodes, all measured in the past 30 days. Outcomes included CP depression, anxiety, anger expression, behaviors related to partner drinking (i.e., four SBQ subscales of punishing drinking, supporting sobriety, supporting drinking, withdrawing), and relationship quality. The first research question examined how CP drinking was uniquely associated with mental health symptoms, responses to partner drinking, and relationship quality at baseline beyond perceived partner drinking. Our second research question evaluated whether CP drinking moderated intervention efficacy, tested by examining the interaction between intervention condition and baseline CP drinking on follow-up outcomes.

Covariates included in all models were age, CP education (dummy-coded college graduate or higher vs. less than college graduate), military status (dummy-coded veteran vs. active duty/reserve/guard) and enlisted status (dummy-coded enlisted vs. officer). We controlled for age and partner military status because younger service members drink more heavily (Institute of Medicine, 2012; Seal et al., 2011). Further, active service members face unique significant help-seeking barriers that veterans may not face (e.g., no mandated reporting guidelines for veterans; Institute of Medicine, 2012) and veterans engage in more frequent binge drinking than active duty service members and reserve/guard (Ramchand et al., 2011). We controlled for enlisted versus officer status because heavy drinking is significantly associated with lower paygrade following deployment (Mustillo et al., 2015). Finally, we controlled for CP education because CPs in the control condition were significantly more educated than intervention CPs at baseline. To test for changes in outcomes in the model evaluating the intervention × CP drinking interaction, the baseline-reported outcome was also included in the model. In the case of significant interactions, follow-up tests of simple slopes evaluated intervention effects for relatively light (−1 SD) and heavy (+1 SD) drinking CPs. Interactions and respective follow-up tests included use of grand-mean centered predictors.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Examinations

Descriptive statistics (i.e., means and standard deviations) on all variables at baseline are provided for the entire sample and by intervention condition (with associated tests) in Table 1. There were no significant differences in drinking or outcome variables by condition at baseline.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Psychological and Relational Well-being among Concerned Partners at Baseline

| Intervention Condition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Target | Characteristic | Total Sample n=234 |

Intervention n=136 |

Control n=98 |

t |

| Concerned | Drinks per week | 4.06 (7.66) | 4.32 (7.14) | 3.69 (8.34) | −.62 |

| Partner | Drinking frequency | 4.88 (7.03) | 4.99 (6.94) | 4.74 (7.20) | −.26 |

| Number of heavy drinking episodes | 1.48 (4.10) | 1.61 (4.20) | 1.30 (3.96) | −.55 | |

| Depression | 7.06 (4.49) | 7.24 (4.72) | 6.80 (4.15) | −.74 | |

| Anxiety | 6.67 (4.92) | 6.84 (5.21) | 6.44 (4.51) | −.60 | |

| Anger expression | 35.55 (13.48) | 36.98 (13.46) | 33.43 (13.30) | −1.92† | |

| Relationship quality | 35.30 (13.49) | 34.17 (13.37) | 36.85 (13.56) | 1.50 | |

| Communicating concern | 10.94 (3.82) | 11.11 (3.87) | 10.69 (3.76) | −.83 | |

| Supporting abstinence | 22.47 (5.14) | 22.32 (4.93) | 22.67 (5.44) | .51 | |

| Supporting drinking | 5.55 (1.99) | 5.48 (1.90) | 5.64 (2.11) | .58 | |

| Withdrawing from P | 6.85 (2.58) | 7.03 (2.59) | 6.60 (2.55) | −1.22 | |

| Perceived | Drinks per week | 27.23 (20.59) | 27.15 (20.11) | 27.34 (21.35) | .07 |

| Partner | Drinking frequency | 19.80 (9.38) | 20.04 (9.11) | 19.47 (9.79) | −.45 |

| Number of heavy drinking episodes | 10.80 (9.22) | 10.30 (9.14) | 11.50 (9.33) | .98 | |

Note.

p < .10

Although not the variable utilized in our primary analyses, we were interested in identifying different types of couples based on their baseline drinking levels. We calculated a “heavy drinking” variable for CPs and their partners by assigning a “1” to those who indicated either the traditional cutoff score of 8+/15+ drinks per week (for women/men, respectively; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2004) or at least one heavy drinking episode in the last 30 days, or a “0” if endorsement of neither. At baseline, 64% of the CPs were not heavy drinkers whereas their partners were; 28% was composed of two heavy-drinking partners; 3% of CPs were heavy drinkers whereas their partners were not, and 5% were partnerships where neither was considered a heavy drinker.

Bivariate correlations among all study variables at baseline are presented in Table 2. All indicators of CP drinking were positively associated with CP depression, anxiety, anger expression (rs ranging .16 to .25, ps ≤ .01), and behaviors that supported their partner’s drinking (rs ranging .27 to .33, ps <.001). CP depression, anxiety, and anger expression were negatively associated with relationship quality (rs ranging −.17 to −.23, ps ≤ .01). Perceived partner drinking was generally not associated with CP depression, anxiety, or anger expression, but perceived partner drinks per week (r = .19, p < .01) and heavy drinking episodes (r = .21, p < .01) were positively associated with CPs’ use of punishing strategies.

Table 2.

Zero-order Correlations among All Study Variables at Baseline

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Drinks per week | -- | |||||||||||||

| 2. Drinking frequency | .74*** | -- | ||||||||||||

| 3. Number of HDEs | .80*** | .63*** | -- | |||||||||||

| 4. Depression | .20** | .17** | .20** | -- | ||||||||||

| 5. Anxiety | .19** | .18** | .16* | .67*** | -- | |||||||||

| 6. Anger expression | .25*** | .19** | .24*** | .49*** | .43*** | -- | ||||||||

| 7. Relationship quality | −.10 | −.10 | −.07 | −.23*** | −.17* | −.23*** | -- | |||||||

| 8. Punishment | .05 | −.04 | .07 | .18** | .21** | .31*** | −.26*** | -- | ||||||

| 9. Support abstinence | −.10 | −.13* | −.04 | −.01 | .01 | −.21** | .17* | .25*** | -- | |||||

| 10. Support drinking | .32*** | .34*** | .27*** | .11† | .03 | .07 | .09 | −.19** | .17* | -- | ||||

| 11. Withdrawal | −.06 | −.08 | −.06 | .28*** | .21** | .15* | −.33*** | .46*** | .12† | −.21** | -- | |||

| 12. PP drinks per week | .08 | −.01 | .10 | .16* | .08 | .05 | −.10 | .19** | .02 | .06 | .10 | -- | ||

| 13. PP drinking frequency | .14* | .21** | .09 | .10 | −.01 | .06 | −.13† | .04 | −.08 | .09 | .04 | .51*** | -- | |

| 14. PP number of HDEs | .08 | .02 | .16* | .10 | .07 | .06 | −.10 | .21** | .08 | .04 | .14* | .79*** | .50*** | -- |

Note.

HDE = heavy drinking episodes. PP = perceived partner.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

RQ1: Concerned Partner Drinking and Mental/Relational Health (Baseline)

This research question examined how drinking among CPs (i.e., drinks per week, drinking frequency, heavy drinking episodes) was associated with their own psychological and relational well-being after accounting for their partner’s drinking. Results are presented in Table 3. Results showed strong, consistent associations between drinking and reduced psychological and relational well-being in CPs. Specifically, heavy drinking CPs exhibited higher depression, anxiety, and anger expression. Additionally, heavy drinking CPs reported higher frequency of supporting their partner’s drinking, and generally less frequent withdrawal from their partner when drinking, as well as lower support for their partner’s sobriety.

Table 3.

CP Outcomes as a Function of Own and Perceived Partner Drinking (N=234)

| Drinks Per Week | Drinking Frequency |

Heavy Drinking Episodes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Outcome | Predictor | b | t | b | t | b | t |

| Depression | Age | .050 | 1.75† | .071 | 1.53 | .081 | 1.76† |

| Enlisted status | .632 | .60 | .820 | .78 | .542 | .52 | |

| Veteran status | 2.233 | 3.39*** | 2.235 | 3.39*** | 2.003 | 2.98** | |

| CP education | −.196 | −.32 | −.688 | −1.12 | −.675 | −1.09 | |

| PP drinking | .026 | 1.86† | .030 | .97 | .023 | .72 | |

| CP drinking | .142 | 3.25** | .079 | 1.88† | .174 | 2.34* | |

| Anxiety | Age | .038 | .73 | .049 | .97 | .061 | 1.18 |

| Enlisted status | −.002 | −.00 | .134 | .12 | −.029 | −.03 | |

| Veteran status | 2.747 | 3.75*** | 2.646 | 3.65*** | 2.553 | 3.35** | |

| CP education | −1.177 | −1.73† | −1.546 | −2.29* | −1.528 | −2.18* | |

| PP drinking | .005 | .35 | −.026 | −.77 | .006 | .16 | |

| CP drinking | .125 | 2.56* | .108 | 2.36* | .126 | 1.50 | |

| Anger | Age | .016 | .11 | .084 | .56 | .089 | .59 |

| Expression | Enlisted status | 1.518 | .47 | 2.046 | .62 | 1.223 | .37 |

| Veteran status | .097 | .05 | .437 | .20 | −.344 | −.15 | |

| CP education | −.628 | −.32 | −2.113 | −1.04 | −1.819 | −.88 | |

| PP drinking | .027 | .56 | .020 | .19 | .006 | .06 | |

| CP drinking | .585 | 4.18*** | .343 | 2.56* | .786 | 3.27** | |

| Punishing | Age | .004 | .10 | .018 | .43 | .020 | .49 |

| P Drinking | Enlisted status | .538 | .58 | .646 | .70 | .418 | .45 |

| Veteran status | .396 | .66 | .462 | .77 | .203 | .33 | |

| CP education | −.919 | −1.64 | −1.155 | −2.06* | −1.011 | −1.77† | |

| PP drinking | .033 | 2.61** | .032 | 1.11 | .087 | 2.97** | |

| CP drinking | .013 | .30 | −.047 | −1.18 | −.005 | −.07 | |

| Supporting | Age | −.023 | −.42 | −.023 | −.42 | −.027 | −.48 |

| P Sobriety | Enlisted status | .228 | .19 | .128 | .11 | .168 | .14 |

| Veteran status | 2.185 | 2.75** | 1.891 | 2.38* | 2.105 | 2.56* | |

| CP education | −1.390 | −1.89† | −1.228 | −1.66† | −1.188 | −1.57 | |

| PP drinking | .001 | .06 | −.006 | −.17 | .059 | 1.48 | |

| CP drinking | −.128 | −2.41* | −.111 | −2.17* | −.142 | −1.53 | |

| Supporting | Age | −.013 | −.62 | −.002 | −.09 | −.001 | −.04 |

| P Drinking | Enlisted status | −.035 | −.07 | .115 | .25 | −.012 | −.03 |

| Veteran status | −.153 | −.51 | .026 | .08 | −.059 | −.19 | |

| CP education | .565 | 2.03* | .442 | 1.57 | .623 | 2.13* | |

| PP drinking | .007 | 1.03 | .003 | .20 | −.001 | −.07 | |

| CP drinking | .112 | 5.67*** | .093 | 4.93*** | .149 | 4.30*** | |

| Withdrawal | Age | .085 | 3.15** | .030 | 3.31** | .098 | 3.60*** |

| Enlisted status | .775 | 1.23 | .825 | 1.28 | .805 | 1.26 | |

| Veteran status | .523 | 1.35 | .268 | .68 | .224 | .55 | |

| CP education | −.882 | −2.45* | −.838 | −2.27* | −.811 | −2.17* | |

| PP drinking | .006 | .70 | .010 | .53 | .036 | 1.83† | |

| CP drinking | −.065 | −2.53* | −.052 | −2.01* | −.103 | −2.27* | |

| Relationship | Age | −.455 | −3.16** | −.488 | −3.40*** | −.534 | −3.66*** |

| Quality | Enlisted status | −.003 | −.00 | −.682 | −.21 | .056 | .02 |

| Veteran status | 4.107 | 2.01* | 3.729 | 1.82† | 3.965 | 1.86† | |

| CP education | 3.677 | 1.94† | 4.292 | 2.25* | 3.795 | 1.93† | |

| PP drinking | −.064 | −1.48 | −.143 | −1.47 | −.150 | −1.49 | |

| CP drinking | −.230 | −1.69† | −.112 | −.86 | −.173 | −.73 | |

Note.

P = partner. PP = perceived partner. CP = concerned partner.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

With regard to associations with perceived partner drinking, results generally showed that perceived partner drinking was not related to CP mental health. Interestingly, perceived partner drinking was also largely unrelated to the behavioral responses to the partner’s drinking. CPs who perceived their partners to drink more heavily were more likely to report use of punishment and withdrawal behaviors. However, perceived partner drinking was unrelated to CP use of supporting sobriety and supporting drinking behaviors. Neither CP drinking nor perceived partner drinking were associated with relationship quality.

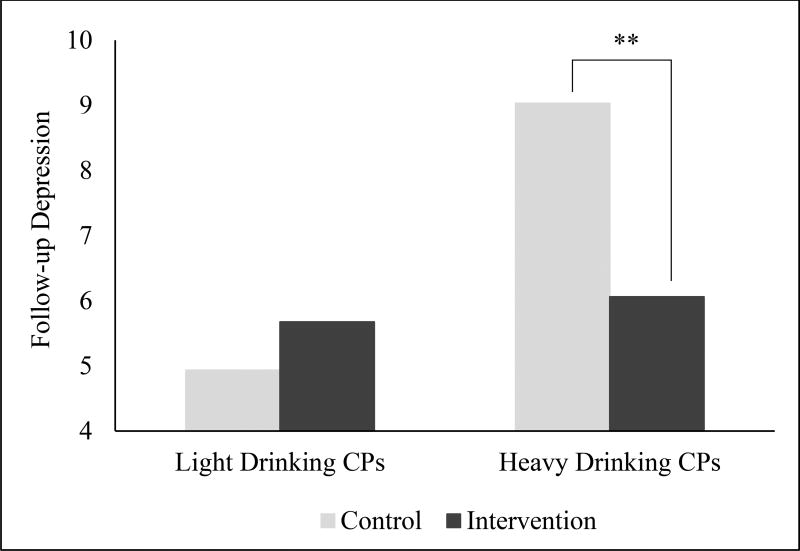

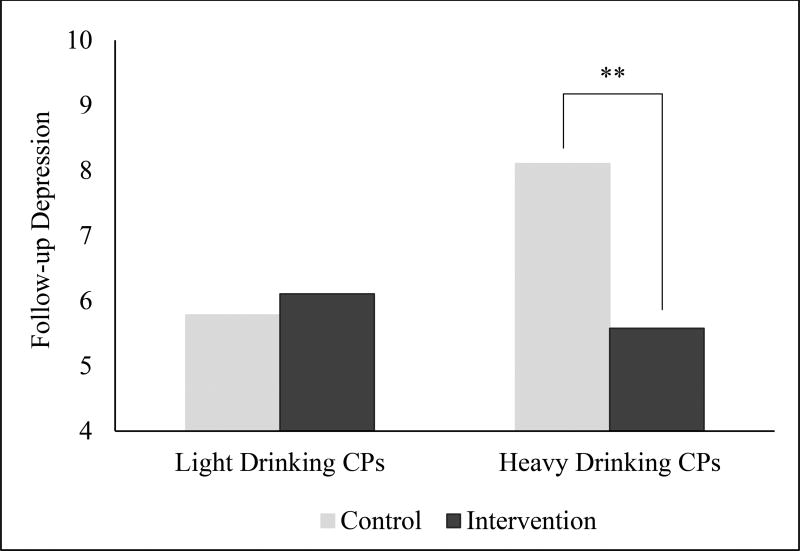

RQ2: Differential Intervention Efficacy by CP Drinking

Our second research question investigated whether the efficacy of the Partners Connect intervention differed as a function of CP drinking at baseline. Overall intervention effects are reported elsewhere (blinded for review). As reported by [blinded for review], models including covariates and intervention condition showed that CPs in the intervention condition reported marginal decreases in depression at follow-up, b = −1.007, t(214) = −1.75, p = .082. Results from moderation analyses revealed two significant interactions between intervention condition and CP drinking (i.e., drinks per week, b = −.242, t(210) = −2.74, p = .007, and drinking frequency, b = −.203, t(207) = −2.50, p = .013) on changes in depression. The interaction between intervention and CP heavy drinking episodes was not significant. Follow-up tests evaluated effects of the intervention on changes in depression for lighter and heavier drinking CPs. Results with simple effects for lighter (−1 SD) and heavier drinkers (+1 SD) are illustrated in Figures 1 (drinks per week) and 2 (drinking frequency). Results showed that, after controlling for baseline values, there were significant reductions in depression as a function of the intervention among heavy drinking CPs (t(210) = −3.26, p = .001 for drinks per week and t(207) = −3.12, p = .002 for drinking frequency); no intervention effect was found among lighter drinking CPs (ps > .35). In other words, the intervention was more efficacious at reducing depression among CPs who were heavier drinkers (both measured via drinks per week and drinking frequency) compared to those who were lighter drinkers. There were no other significant findings related to anxiety, anger expression, or relationship quality.

Figure 1.

Intervention effects on changes in depression moderated by concerned partner drinking levels, as measured by number of drinks per week. ** p < .01

Figure 2.

Intervention effects on changes in depression moderated by concerned partner drinking levels, as measured by drinking frequency. ** p < .01

Supplementary analyses

We evaluated several additional models in supplementary analyses. We tested models after removing the couples whereby the CP was the heavier drinking spouse. Additionally, we tested models including covariates for CP psychological treatment outside of the study and CP utilization of medication for psychological issues. In both cases, results were unchanged. Finally, we examined interactions between own and perceived partner drinking to test whether larger discrepancies in drinking patterns were differentially associated with CP outcomes at baseline or with intervention efficacy. No significant interactions emerged.

DISCUSSION

Heavy drinking among those in relationships is a dynamic and complex issue. While concerned partners (CPs) may primarily seek help for their partners, they may themselves have issues that relate to their own well-being that negatively affect their ability to provide constructive support to their partner. Our study fills research gaps by enhancing understanding of the link between CP drinking and their own mental health beyond the effects of their partner’s drinking, and how CP drinking moderates the efficacy of an intervention designed to help themselves constructively communicate about their partner’s drinking.

First, we found that CPs who drank heavily had more mental health problems (i.e., depression, anxiety, anger expression) and more frequent negative interaction patterns in response to their partner’s drinking at baseline. For example, heavy drinking CPs reported a higher frequency of supporting their partner’s drinking behavior, less frequent withdrawal from their partner when drinking, and lower support for their partner’s sobriety. It is important to note that we found these patterns independent of how much they perceived their partner to drink, highlighting the unique effects of CP drinking on their own communication styles. Our findings underscore the need to screen CPs for heavy drinking and mental health concerns, and to better understand the interactional patterns CPs have in response to their partner’s drinking. Drinking affects relationships in complex ways and therapists may struggle with “where to start.” By starting with the CP by alleviating their mental health symptoms and providing them with tools to effectively communicate, CPs may be better equipped to support behavioral change in their partner.

While we found that heavy drinking CPs had more mental health problems and poorer relationship quality, this was contrary to our hypothesis that lighter drinking CPs would have more negative outcomes because they were in discordant drinking relationships. There may be three possible explanations for these findings. First, research with community samples typically shows that larger drinking discrepancies are associated with greater distress (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2007; Roberts & Leonard, 1998), but previous work has not focused on this association specifically among help-seeking individuals concerned about their partner’s drinking. CPs who perceive problems may be more likely to experience more problems themselves and in their relationship than those not concerned about their partner. Second, we specifically recruited CPs in drinking relationships (both concordant and discordant) where the partner was drinking heavily. Thus, we excluded partners in abstaining relationships or those where their service member or veteran partner did not drink, who tend to evince the best outcomes. Given that this sample is likely composed of discordant and heavy drinking concordant couples, it makes sense that heavy drinking CPs experienced greater depression, anxiety, and anger expression compared with light drinking CPs. Finally, heavier drinking is positively associated with natural consequences and our findings support this – CP drinking is a stronger predictor of mental health symptoms than is their partner’s drinking. These findings may suggest that the effects of partner drinking on the CP are less detrimental if the CP is drinking heavily him or herself.

Second, we found that the Partners Connect intervention was more helpful in reducing depressive symptoms among CPs who drank heavily compared to lighter drinking CPs. The intervention focused on self-care for the CPs and positive communication strategies for discussing their partner’s drinking. Heavier drinking CPs may have benefitted more from the intervention than lighter drinking CPs because they were experiencing more problems at baseline and the tools in the intervention may have helped them cope with depression symptoms in more effective ways. Although we did not develop the intervention to target CP drinking, in light of the present findings future interventions would benefit from including strategies focusing on reducing CP drinking and examining longer term outcomes to evaluate whether depression mediates reductions in CP drinking. These findings suggest that interventions tailored specifically to the problems CPs are facing are important to address.

Of note is that neither CP drinking nor perceived partner drinking were associated with relationship quality. This finding runs contrary to the results of studies examining drinking concordance between relationship partners; these studies generally find that concordant couples (including those with two drinking partners) have higher relationship quality than do discordant couples. In addition, the intervention did not influence changes in relationship quality differently based on CP drinking. However, these findings must be considered in light of the relatively low sample relationship quality at the outset (M=35.3 on a scale of 6 to 60). It is possible that results with relationship quality occurred because CPs were generally unhappy with their relationships due to other factors (e.g., deployments, financial strains), regardless of how much they or their partners drank. Moreover, considering the CPs sought out an intervention to help themselves manage and help decrease their partner’s drinking, future work may benefit from further exploration into links between own and perceived partner drinking and relationship quality.

Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

There are at least two main clinical implications from this research. First, the importance of screening CPs for their own drinking and mental health concerns is important and may be essential before working on dyadic patterns of interaction within the couple or changing their partner’s drinking. CPs experience significant concerns of their own that may prohibit them from effectively supporting their partner, and may inadvertently increase relationship conflict. If the needs of CPs are met, they may be a gateway to helping change their partner’s drinking and improve their relationship quality. Research on concordant heavy drinking couples shows that when one spouse stops drinking, the odds of the other spouse quitting is five times larger than if the spouse continued to drink (Falba & Sindelar, 2008). Men and women are significantly more likely to make any health behavior change when their partner does as well, such as when one quits smoking or increases physical activity (Jackson, Steptoe, & Wardle, 2015). Thus, focusing on alleviating the CP’s drinking and mental health problems is highly likely to benefit the other partner and the couple’s relationship quality, which—given the bidirectional relationship between drinking and relationship distress (Marshal, 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2014)—may have downstream effects on reducing the partner’s drinking.

Second, a web-based intervention may be a promising approach and a logical first step for engaging CPs who may not otherwise seek care because of stigma and other help-seeking barriers (Eaton et al., 2008). CPs may be more motivated to participate in an intervention if framed at helping their family and their loved one who drinks heavily. This may have helped those who actually needed help with heavy drinking and/or mental health enroll into an intervention study that directly benefitted their own problem behaviors (as evidenced by reductions in depression by the heavy drinking CPs). While the advertisement was focused on helping their partner, the skills can also be applied to themselves to cope and communicate in healthier ways. This allows CPs to experience dual empowerment; by facilitating some control over what both they are doing as well as potentially what their partner is doing, they not only help themselves, but also help their families. Future investments in making web-based interventions available to CPs would fill a significant clinical need among underserved CPs in the military and in the general population, and may help engage CPs into subsequent services. A web-based intervention could also serve as an adjunct to in-person therapy where a CP engages in the web-based intervention in between sessions as homework and practice. Young adults may be particularly interested in online tools to supplement their therapy that they can access anywhere with an internet connection.

This research should be viewed in light of its limitations. First, the intervention did not include partner data. Future research may wish to incorporate both members of the dyad to jointly address issues regarding perceptions around each person’s drinking, with the objective of improving drinking, communication, and relationship outcomes for both partners. We would also like to compare the efficacy of this intervention as a standalone (as currently designed) program to couples-based therapies to better understand what helps the CP most. Finally, understanding motives underlying heavy drinking by CPs would facilitate targeting future intervention efforts to help reduce drinking and improve mental health. For example, if CPs in these relationships tend to drink heavily to cope with their partner’s alcohol use patterns, interventions could hone in on strategies to cope in healthier ways.

In conclusion, military CPs in relationships with a drinking partner are at greater risk for emotional distress and our research highlights this is especially true with CPs who drink heavily themselves. Concerned partners are often an underrepresented group for resources and this novel work provides insight into how CP alcohol use plays a unique role in their own mental health irrespective of their partner’s drinking that can benefit from tailored intervention efforts.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; 1R34AA023123, Principal Investigator: Karen Chan Osilla). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Trial registration

References

- Ahmadi H, Green SL. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for military spouses experiencing alcohol and substance use disorders: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2011;18:129. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Previti D. People's reasons for divorcing gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(5):602–626. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(6):580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell NS, Harford TC, Fuchs CH, McCarroll JE, Schwartz CE. Spouse abuse and alcohol problems among White, African American, and Hispanic US Army soldiers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(10):1721–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth B, Segal MW, Bell DB, Martin JA, Ender MG, Rohall D, et al. What we know about army families: 2007 update. Fairfax, VA: Caliber; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Brown JM, Williams J. Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the US military. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48(10):799–810. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Hourani LL, Witt M, Rae Olmsted KL, Brown JM, Weimer BJ, Lane ME, Marsden ME, Scheffler SA, Vandermaas-Peeler R, Aspinwall KR, Anderson EM, Spagnola K, Close KL, Gratton JL, Calvin SL, Bradshaw MR. 2008 Department of Defense survey of health related behaviors among active duty military personnel. Washington, DC: TRICARE Management Activity; 2009. Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs) and U.S. Coast Guard under Contract No. GS-10F-0097L. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Ziegler I, Ilgen M, Valenstein M, Zivin K, Gorman L, Blow A, Duffy S, Chermack S. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse among returning Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:801–806. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Floyd FJ, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Husbands' and wives' alcohol use disorders and marital interactions as longitudinal predictors of marital adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(1):210–222. doi: 10.1037/a0021349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Burgh HT, White CJ, Fear NT, Iversen AC. The impact of deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan on partners and wives of military personnel. International Review of Psychiatry. 2011;23(2):192–200. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.560144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rowe LS, Morrison KR, Libet J, Birchler GR, Madsen JW, McQuaid JR. Couple therapy for military veterans: Overall effectiveness and predictors of response. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(1):216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton KM, Hoge CW, Messer SC, Whitt AA, Cabrera OA, McGurk D, Castro CA. Prevalence of mental health problems, treatment need, and barriers to care among primary care-seeking spouses of military service members involved in Iraq and Afghanistan deployments. Military Medicine. 2008;173(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.173.11.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Meis LA, Polusny MA, Arbisi PA. Psychiatric distress among spouses of National Guard soldiers prior to combat deployment. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2012;9(3):161–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falba TA, Sindelar JL. Spousal concordance in health behavior change. Health Services Research. 2008;43(1p1):96–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, Heyman RE, Slep AMS, Snarr JD. Hazardous alcohol use and intimate partner violence in the military: understanding protective factors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):471–483. doi: 10.1037/a0027688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(4):365–371. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Bouma R, Kelly A, Young RM. Individual psychopathology and marital distress Analyzing the association and implications for therapy. Behavior Modification. 1999;23(2):179–216. doi: 10.1177/0145445599232001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Alcohol use, alcohol problems, and depressive symptomatology among newly married couples. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83(3):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Substance Use Disorders in the US Armed Forces. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Steptoe A, Wardle J. The influence of partner’s behavior on health behavior change: the English longitudinal study of ageing. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(3):385–392. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;114(1):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley K, Clark CL, Caetano R. Couples' drinking patterns, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related partnership problems. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11(3):253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Jacob T. Handbook of Family Violence. Springer; US: 1988. Alcohol, alcoholism, and family violence; pp. 383–406. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(3):369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, Forsyth B, Bose J, Kroutil LA, Lane ME. Spouses and children of U.S. military personnel: Substance use and mental health profile from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2016 Nov; NSDUH Data Review. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Love CT, Longabaugh R, Clifford PR, Beattie M, Peaslee CF. The Significant-other Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ): An instrument for measuring the behavior of significant others towards a person's drinking and abstinence. Addiction. 1993;88(9):1267–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, McKay JR, O'Farrell TJ. Twelve-month abstinence from alcohol and long-term drinking and marital outcomes in men with severe alcohol problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(5):591–598. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(7):959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudar P, Leonard KE, Soltysinski K. Discrepant substance use and marital functioning in newlywed couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(1):130–134. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustillo SA, Kysar-Moon A, Douglas SR, Hargraves R, Wadsworth SM, Fraine M, et al. Overview of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and alcohol misuse among active duty service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, self-report and diagnosis. Military Medicine. 2015;180(4):419–427. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician's guide 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Sloan FA, Taylor DH. Heavy alcohol use and marital dissolution in the USA. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(11):2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul LA, Grubaugh AL, Frueh BC, Ellis C, Egede LE. Associations between binge and heavy drinking and health behaviors in a nationally representative sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1240–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Helmuth ED, Marshall GN, Schell TL, Punkay M, Kurz J. Using Facebook to recruit young adult veterans: Online mental health research. JMIR Research Protocols. 2015;4(2) doi: 10.2196/resprot.3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Kurz J. Using Facebook for health-related research study recruitment and program delivery. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2016;9:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Osilla KC, Helmuth ED, Tolpadi A, Gore KL. Reaching concerned partners of heavy drinking service members and veterans through Facebook. Military Behavioral Health (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Wade M, Andersen J, Ouimette P. The impact of PTSD, depression, and substance use disorders on disease burden and health care utilization among OEF/OIF veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2(3):218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Miles J, Schell T, Jaycox L, Marshall GN, Tanielian T. Prevalence and correlates of drinking behaviors among previously deployed military and matched civilian populations. Military Psychology. 2011;23(1):6–21. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.534407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LJ, Leonard KE. An empirical typology of drinking partnerships and their relationship to marital functioning and drinking consequences. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM. A dyadic growth approach to partner regulation attempts on changes in drinking and negative alcohol-related consequences. Substance Use and Misuse. 2016;51(14):1870–1880. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1200621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, DiBello AM, Neighbors C. Perceptions of partner drinking problems, regulation strategies and relationship outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2949–2957. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Knee CR. Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: An interdependence theory perspective. Addiction Research and Theory. 2014;22:294–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Farrow VA, Ross J, Oslin DW. Family problems among recently returned military veterans referred for a mental health evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):163–170. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;116:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal MW. The military and the family as greedy institutions. Armed Forces & Society. 1986;13:9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Staxi-2: State-trait anger expression inventory-2: Professional manual. PAR, Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart Richard B. Operant-interpersonal treatment for marital discord. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33(6):675. doi: 10.1037/h0028475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik FA, Gustavson K, Røysamb E, Tambs K. Health, health behaviors, and health dissimilarities predict divorce: Results from the HUNT study. BMC Psychology. 2015;3(13):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0072-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik FA, Røysamb E, Gustavson K, Idstad M, Tambs K. Discordant and concordant alcohol use in spouses as predictors of marital dissolution in the general population: Results from the HUNT study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(5):877–884. doi: 10.1111/acer.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RL, Hops H, Patterson GR. A framework for conceptualizing marital conflict: A technology for altering it, some data for evaluating it. In: Handy LD, Mash EL, editors. Behavior change: Methodology, concepts, and practice. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1973. pp. 309–342. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma JD, Fischer JL. Young adult drinking partnerships: Alcohol-related consequences and relationship problems six years later. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(4):704–712. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JO, Bell NS, Amoroso PJ. Drinking and other risk taking behaviors of enlisted male soldiers in the US Army. Work. 2002;18(2):141–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]