Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of intrasphincteric injections of autologous myoblasts (AMs) in fecal incontinence (FI) in a controlled study.

Summary of Background Data:

Adult stem cell therapy is expected to definitively cure FI by regenerating damaged sphincter. Preclinical data and results of open-label trials suggest that myoblast therapy may represent a noninvasive treatment option.

Methods:

We conducted a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of intrasphincteric injections of AM in 24 patients. The study compared outcome after AM (n = 12) or placebo (n = 12) injection using Cleveland Clinic Incontinence (CCI), score at 6 and 12 months. Patients in the placebo group were eligible to receive frozen AM after 1 year.

Results:

At 6 months, the median CCI score significantly decreased from baseline in both the AM (9 vs 15, P = 0.02) and placebo (10 vs 15, P = 0.01) groups. Hence, no significant difference was found between the 2 groups (primary endpoint) at 6 months. At 12 months, the median CCI score continued to ameliorate in the AM group (6.5 vs 15, P = 0.006), while effect was lost in the placebo group (14 vs 15, P = 0.35). Consequently, there was a higher response rate at 12 months in the treated than the placebo arm (58% vs 8%, P = 0.03). After delayed frozen AM injection in the placebo group, the response rate was 60% (6/10) at 12 months.

Conclusions:

Intrasphincteric AM injections in FI patients have shown tolerance, safety, and clinical benefit at 12 months despite a transient placebo effect at 6 months.

Keywords: autologous myoblasts, cell therapy, fecal incontinence, stem cells

Fecal incontinence (FI) is a frequent debilitating condition affecting approximately 8% to 11% of the population1. Initial treatment options include modifying bowel activity with diet, antidiarrheal medication, and biofeedback techniques. When insufficient, surgery should be considered. Sphincter repair is possible for limited sphincter rupture, but outcome deteriorates over time, with failure rates of up to 72% within 5 years.2–4 Injection of bulking agents has resulted in variable rates of success.5–7 Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) has become the first-line surgical procedure because of its good tolerance and long-term success rate of 60%.8 However, it requires regular changing of the pacemaker (approximately every 5 years) and remains costly in the long run.9,10

In case of SNS failure, sphincter substitution (eg, artificial bowel sphincter implantation or stimulated graciloplasty) is the only alternative to a stoma. However, this surgical procedure is invasive with high morbidity, variable success rates with deterioration in effectiveness over time and is not available in some countries.9 Other approaches such as injection of bulking agents into the anal sphincter complex have been introduced but provide inconsistent results7; their role in the treatment algorithm for FI remains to be confirmed. In the same way, radiofrequency (SECCA procedure) has been abandoned by many centres11 and the magnetic anal sphincter is still being evaluated.12,13

As a result, the current therapies for FI remain dramatically insufficient to meet therapeutic needs and permanent colostomy is still required for some patients.

Adult stem cells have the potential to provide definitive cure of disease by regenerating damaged tissue. Cell therapy using myoblasts is feasible because these cells can be obtained from muscle biopsies and expanded in culture under clinical-grade conditions. Their injection into damaged muscle has shown excellent tolerance, as evidenced from early clinical trials in patients with muscular dystrophy14,15 or heart failure.16,17 Autologous myoblasts have been proposed for treating urinary incontinence, with encouraging results and few side effects.18,19 We recently provided proof of principle for myoblast cell therapy to treat FI in a rat model in which injection of myoblasts in the anal sphincter resulted in restoration of sphincter pressures.20 A pilot open-label clinical study21,22 reported substantial amelioration of continence and improved quality of life in 10 patients with FI, as assessed by the Cleveland Clinic Incontinence (CCI) and the Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) scores, respectively.

However, the effect of myoblasts in treating FI has not yet been evaluated in a controlled study. Therefore, we investigated the safety and efficacy of intrasphincteric injections of autologous myoblasts (AMs) in patients with severe FI and sphincter insufficiency.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study and has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT01523522).

Patients

From March 2012 to June 2014, 24 patients with FI were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were age 20 to 65 years; severe FI for at least 3 months defined as a CCI score 23 of 10 or more [range (0, normal—20, most severe)]; FI due to sphincter deficiency [single defect, multiple disruption or degeneration of the external anal sphincter (EAS) diagnosed by endosonography] and refractory to conservative treatment, that is, medical treatment and biofeedback. Exclusion criteria were lesion of EAS >30% circumference; myopathy; decompensated diabetes; inflammatory bowel disease; and inability to comprehend the preoperative questionnaire.

Before enrollment, all patients had clinical assessment, anorectal manometry, endoanal ultrasonography, perineal electrophysiological tests, and defeco-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). After having given written informed consent, all patients completed the CCI form23 and the French version of the FIQL questionnaire.24,25 The protocol was approved by the Haute-Normandie Ethics Committee (France) and authorized by the competent authority. Completion of the study was reviewed periodically by an expert committee independent of the investigators (1 methodologist, 1 digestive surgeon, 1 cell therapy expert); the committee had access to all data, gave advice on the imputability of adverse effects, and authorized delayed injection of AM for the placebo group.

The primary endpoint was the decrease in CCI score between the initial and the 6-month injection in the AM vs placebo groups. Secondary endpoints were variation in CCI score at 12 months relative to baseline; response rate (≥30% reduction in CCI scores) at 6 and 12 months, as recommended26,27; variation at 6 and 12 months in FIQL score, anorectal manometry, and ultrasonography data relative to baseline.

Randomization and Blinding

Randomization was executed by means of envelopes that were prepared and sequentially numbered by the Department of Biostatistics of our tertiary care center, and then communicated to the biotherapy facility of the same center at the latest stage of myoblast production for syringe preparation. Patients and the surgeon remained unaware of the syringe content until at least the 6-month evaluation of the primary endpoint.

Procedure and Myoblast Preparation

For all patients, a quadriceps biopsy (0.4 to 1.5 g) was performed under local anesthesia, and the resulting sample was immediately transferred to the biotherapy facility. The muscle fragment was minced and enzymatically digested with collagenase NB6 (Serva electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany). Then, isolated cells were cultured in a myoblast selection medium containing 10% clinical-grade fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for approximately 3 weeks. Myoblasts were then amplified for approximately 1 week in an expansion medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and 10 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). At that stage, the biotherapy facility was informed of the randomization data by the Department of Biostatistics.

The cell therapy product consisted of the cells harvested at the third passage (P3). In-process and/or final criteria for release included cell number, cellular viability, percentage of myoblast-specific CD56+ cells, and sterility and absence of endotoxins. For the AM arm, cells were conditioned in 8 syringes of 12.5 ± 2.5 × 106 cells in 1.6% human albumin (VIALBEX, LFB, Les Ulis, France) and saline. For the placebo arm, syringes were filled with saline supplemented with 1.6% albumin, whereas cells harvested at P3 were frozen in 6% dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) and 4% human albumin. Percentages of CD56+ cells and other phenotypic information are given in Supplementary Figure 1.

Implant Procedures

Implant procedures were performed in outpatient conditions. All patients received rectal preparation with povidone iodine, the morning before surgery. Patients were placed in the lithotomy position, then the perineum was disinfected and local anesthetic drug (Lidocaine 1%) was injected subcutaneously.

The administration of 100 ± 20 × 106 AM or placebo was performed, by the surgeon principal investigator, as 8 injections in the EAS into the existing residual muscle under endoanal echography guidance and circumferentially.

Patients were monitored during 3 hours with pain assessed using visual analogue scale. All patients received a 7-day course of antibiotics (cefuroxime, metronidazole) and a biofeedback re-education program 15 days post-injection.

Follow-Up

The follow-up visits scheduled at 6 and 12 months consisted in completion of CCI and FIQL scores, anorectal manometry, perineal electrophysiological tests, anal endosonography, and MRI. Undesirable clinical occurrences of any kind were classified as adverse events.

Unblinding was performed after recording the evaluation criteria at the 6-month visit, so that patients randomized to the placebo arm could be offered the possibility of receiving a delayed (after the 12-month visit) injection of their AM. Approval from the independent expert committee was required before injection.

Sample Size Calculation

From a pilot study on AM injection in 10 patients with FI, Frudinger et al reported a mean CCI score decrease at 12 months of 13.7, with a 4.1 standard deviation (deduced from their reported 95% confidence interval), corresponding to a 3.3 effect size (ratio of 13.7 mean decrease to 4.1 standard deviation). At 6 months, the mean decrease was also 13.7 but no standard deviation or confidence interval was reported for the CCI score decrease. In order to guard against overoptimism from a pilot study, we considered a much smaller difference between the AM and placebo groups, that is, an effect size of 1.353 (41% of that reported by Frudinger et al21). For instance, this would correspond to a difference in mean CCI score decrease at 6 months of 13.7 vs 8.2 in the AM and placebo groups, respectively, or 10.0 vs 4.5, in both cases with a common standard deviation still at 4.1. In order to achieve 80% power relative to this between-group difference for a 2-sided 0.05 significance level with the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test, the target sample size was 24 patients, 12 in each group.

Statistical Analysis

For quantitative outcomes, intragroup absolute change from baseline was assessed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-ranked test. Between-group differences were assessed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Median and range are reported unless otherwise noted. Counts and percentages are reported for categorical data. For all statistical tests, a 2-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Data

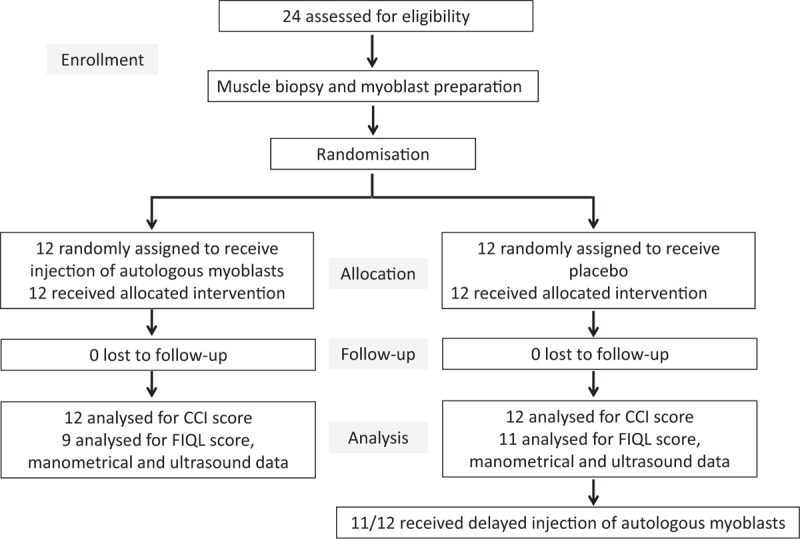

Overall, 24 women of median age 52 (range, 24–64) years were randomly assigned to receive either AM or placebo injections (Fig. 1). Their median body mass index was 24.2 (17.2 to 31.5) kg/m2. Eight patients had a previous history of surgery for FI, including sphincter repair (n = 3), SNS (n = 4), and rectopexy (n = 1). All 24 patients had EAS insufficiency, among whom 14 had a rupture <30% objectified on endoanal ultrasonography. In addition, 9 patients also had an internal anal sphincter defect. There were no appreciable differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 treatment groups, except perhaps for 1 FIQL component. Notably, the CCI score and physiological findings were not different between the 2 groups (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow-chart.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics and Baseline Values

| Placebo (n = 12) | Myoblasts (n = 12) | P | |

| Age, yrs | 52 [25; 64] | 51 [24; 61] | NS |

| Duration of symptoms, mo | 78 [10; 240] | 30 [12; 120] | NS |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.2 [18.2; 31.5] | 24.2 [17.2; 30.9] | NS |

| Number of vaginal deliveries per patient | 3 [1; 4] | 2 [1; 5] | NS |

| Menopause | 7 (58%) | 6 (50%) | NS |

| Main origin of incontinence (Obstetrical/Neurogenic/Iatrogenic) | 8/3/1 | 7/5/0 | |

| Cleveland Clinic Incontinence score | 15 [10; 18] | 15 [10; 18] | NS |

| FIQL score | |||

| Lifestyle | 2.30 [1.20; 3.60] | 1.90 [1.00; 3.60] | NS |

| Coping and behavior | 1.75 [1.10; 2.80] | 1.30 [1.00; 3.10] | NS |

| Depression and self-perception | 3.30 [2.00; 3.50] | 2.55 [1.00; 4.30] | 0.04* |

| Embarrassment | 1.65 [1.00; 2.70] | 1.65 [1.00; 2.70] | NS |

| Previous treatment | |||

| Antidiarrheal drug treatment | 7 (58%) | 7 (58%) | NS |

| Biofeedback | 12 (100%) | 12 (100%) | NS |

| Surgery | 4 (33%) | 4 (33%) | NS |

| Sphincter insufficiency (%) | |||

| FI with external sphincter insufficiency | 12 (100%) | 12 (100%) | NS |

| Defect of external sphincter | 7 (58%) | 7 (58%) | NS |

| Defect of internal sphincter | 5 (42%) | 4 (33%) | NS |

| Associated neurological dysfunction | 5 (42%) | 6 (50%) | NS |

| Anorectal manometric measurements | |||

| Resting pressure, cm H2O | 52.5 [28; 85] | 54.5 [16; 106] | NS |

| Squeeze pressure, cm H2O | 34 [0; 147] | 38 [0; 131] | NS |

| Squeeze pressure duration, s | 28 [0; 46] | 12.5 [0; 107] | NS |

Values are expressed as number (%) or median [range].

*P < 0.05 using the Mann-Whitney test.

FI indicates fecal incontinence; FIQL, fecal incontinence quality of life; NS, not significant.

Myoblast Preparation

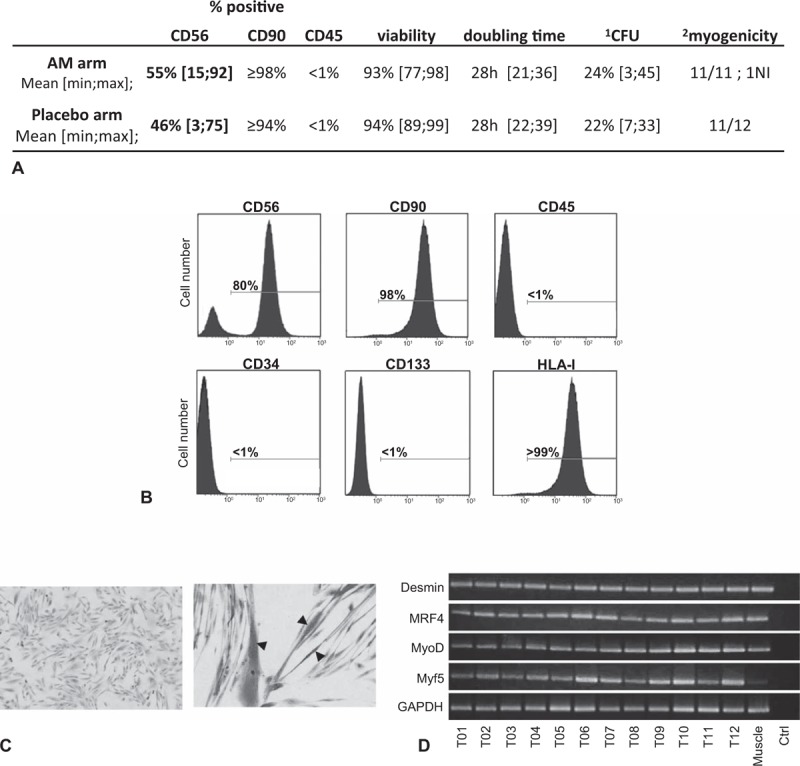

Myoblasts were prepared from a muscle biopsy after 3 to 4 weeks of culture. Cell preparations were CD90+, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I+, CD45−, CD34−, and CD133−, containing a similar frequency (±standard deviation) of 55 ± 7% and 46 ± 7% of CD56+ cells (difference not significant) for the AM and placebo arms, respectively (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 1), and were sterile. Their average doubling time was 28 hours, seeded cells gave rise to colonies [range 3% to 45% colony-forming units (CFUs)], and myogenic potential was evidenced in most samples. Cell preparations expressed mRNA transcripts of typical molecular markers of myogenic cells such as desmin, MRF4, Myf5, MyoD, and Pax7 (Fig. 2D). As expected, some nonrecurrent genomic abnormalities related to the cell culture process were evidenced by karyotypic and FISH analyses (Supplemental Table 2) but were not associated with a risk of transformation, in accordance with our previous report.28 Notably, all cell preparations lost CD56 positivity after serial passages and always became senescent (Supplemental Figure 1A-B). None re-expressed telomerase (Supplemental Figure 1C), grew in soft agar (Supplemental Figure 2), or expressed mutated p53 (Supplemental Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of myoblast preparation. A, Immunophenotype and growth characteristics of myoblast preparations. B, Example of immunophenotype for myoblast preparation (T02): flow cytometry analysis after staining with anti-CD56, anti-CD90, anti-CD45, anti-CD34, anti-CD133 and anti-HLA-I monoclonal antibodies. Complete phenotypic results appear in supplemental Table 1. C, Example of undifferentiated myoblasts for P07 (left, magnification 100×) and myogenic differentiation (right, magnification 200×) in appropriate culture medium. Arrowhead, multinucleated fiber. Giemsa staining. D, RT-PCR analysis of desmin and myogenic factor (MRF4, MyoD, and Myf5) gene expression. cDNAs were from the 12 different myoblast preparations from the treated arm and from 1 normal muscle sample. Control is RT-PCR without RNA template at the RT step. ∗CFU, colony-forming units (20 or 40 cells/well, 6 wells); †Capacity of clones to give rise to plurinucleated myotubes. AM indicates autologous myoblasts; NI, not interpretable.

Effect on Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score

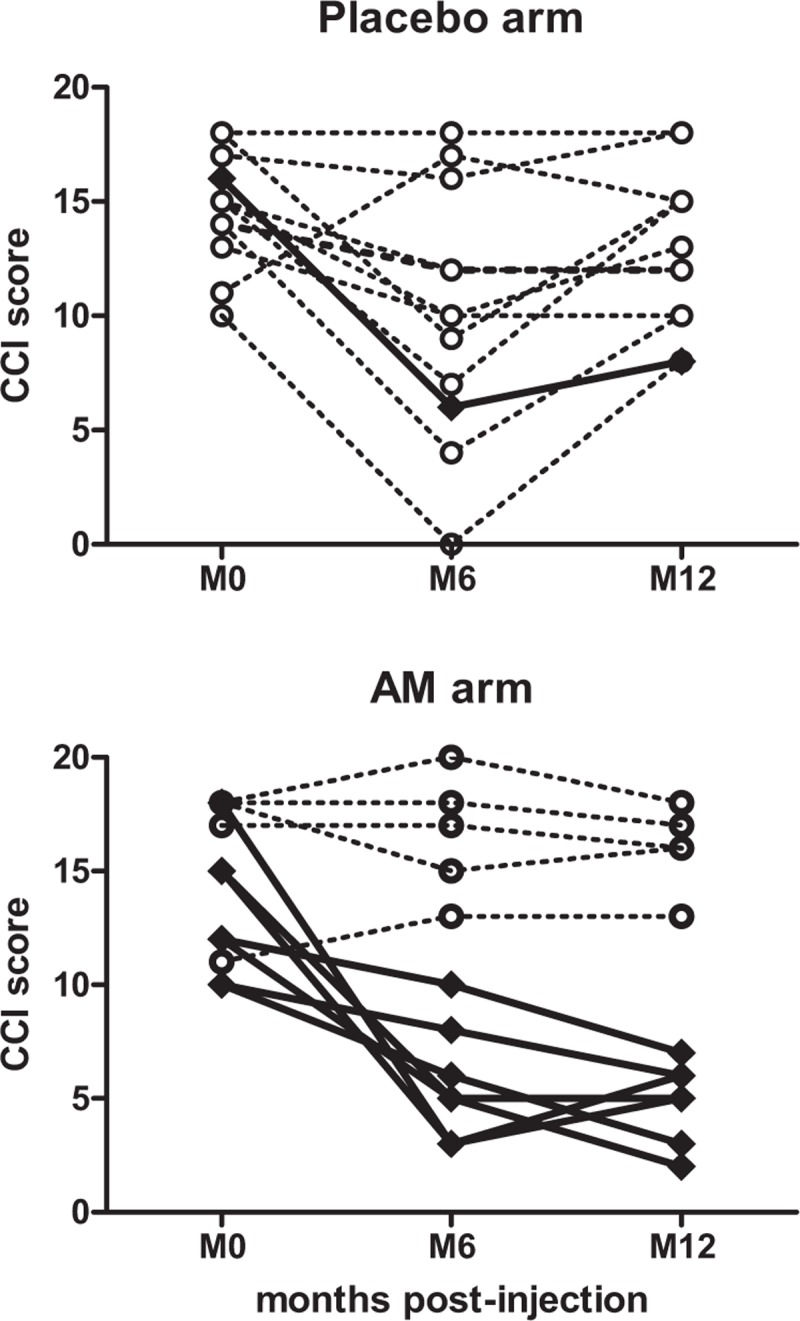

Injection of 100 ± 20 × 106 AM or placebo was performed as 8 injections directly in the EAS under endoanal echography guidance. At 6-month postinjection visit, median CCI score decreased significantly from baseline in both the AM (9 vs 15, P = 0.02) and placebo (10 vs 15, P = 0.01) arms (Table 2, Fig. 3). Due to this important but unanticipated placebo effect, the improvement in the CCI score in the AM group was not statistically different from that observed in the control group. Indeed, 6 of 12 patients (50%) having received the placebo appeared as responders at 6 months (30% or greater reduction in the CCI score) as compared with 5 of 12 patients (41.7%) having received AM.

TABLE 2.

CCI and FIQL Score Results of the 24 Patients at Baseline and After 6 and 12 Months

| Placebo | |||||||

| Baseline | M6 | M12 | Change Baseline/M6 | P | Change Baseline /M12 | P | |

| n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | |||

| Cleveland Clinic Incontinence score* | 15 [10; 18] | 10 [0; 18] | 14 [8; 18] | −4 [−10; 6] | 0.01* | −2 [−8; 6] | 0.35 |

| n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 11 | n = 12 | n = 11 | |||

| FIQL: Lifestyle | 2.3 [1.2; 3.6] | 2.5 [1.0; 4.0] | 2.0 [1.6; 3.8] | 0 [−0.4; 1.5] | 0.43 | −0.3 [−1.2; 2.2] | 0.30 |

| FIQL: Coping and behavior | 1.8 [1.1; 2.8] | 2.1 [1.1; 3.7] | 1.8 [1.2; 3.6] | 0 [−0.5; 1.6] | 0.52 | 0 [−1.4; 2.2] | 0.61 |

| FIQL: Depression and self-perception | 3.3 [2.0; 3.5] | 3.2 [1.7; 4.6] | 3.0 [2.0; 4.2] | −0·1 [−1.0; 1.3] | 0.95 | −0.2 [−1.3; 1.0] | 0.57 |

| FIQL: Embarrassment | 1.7 [1.0; 2.7] | 2.0 [1.0; 4.0] | 2.0 [1.3; 3.7] | 0 [−0.3; 2.4] | 0.17 | 0.3 [−0.4; 2.7] | 0.45 |

| Autologous Myoblasts | |||||||

| Baseline | M6 | M12 | Change Baseline/M6 | P | Change Baseline/M12 | P | |

| n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | |||

| Cleveland Clinic Incontinence score* | 15 [10; 18] | 9 [3; 20] | 6.5 [2; 18] | −2.5 [−15; 2] | 0.02* | −4.5 [−12; 2] | 0.006* |

| n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 9 | n = 12 | n = 9 | |||

| FIQL: Lifestyle | 1.9 [1.0; 3.6] | 2.3 [1.1; 3.9] | 2.6 [1.0; 4.0] | 0.3 [−0.5; 2.1] | 0.07 | 0.7 [−0.3; 2.0] | 0.03* |

| FIQL: Coping and behavior | 1.3 [1.0; 3.1] | 1.6 [1.0; 4.0] | 1.9 [1.0; 3.8] | 0.1 [−0.1; 2V3] | 0.04* | 0.5 [−0.1; 2.0] | 0.02* |

| FIQL: Depression and self-perception | 2.6 [1.0; 4.3] | 2.5 [1.2; 4.2] | 3.0 [1.2; 4.3] | 0.1 [−0.9; 1.5] | 0.40 | 0.4 [−0.3; 1.5] | 0.05 |

| FIQL: Embarrassment | 1.7 [1.0; 2.7] | 1.7 [1.0; 3.7] | 1.7 [1.0; 3.7] | 0.2 [−1.0; 2.4] | 0.12 | 0 [−1.0; 1.7] | 0.19 |

Values are expressed as median [range].

The quality-of-life score for each scale ranges from 1 to 4 (1 = poorest and 4 = best quality-of-life), except for the depression/self-perception scale, scored 1 (very poor quality-of-life) to 4.43 (excellent quality-of-life).

*P < 0.05 using the Wilcoxon signed-ranked test.

CCI indicates Cleveland Clinic Incontinence score; FIQL, fecal incontinence quality of life; M12, month 12; M6, month 6.

FIGURE 3.

Change in Cleveland Clinic Incontinence score at 6 and 12 months post-injection. Responder (≥30% reduction in CCI score at 12 months as compared with baseline) and nonresponder patients are depicted by diamonds/plain line and circles/dotted line, respectively.

At 12 months, median CCI score continued to ameliorate significantly in the AM arm (6.5 vs 15, P = 0.006) in marked contrast with the control arm in which the placebo effect was lost (14 vs 15, P = 0.35) (Table 2, Fig. 3). Consequently, the 12-month response rate was significantly higher in the AM arm than in placebo (58% vs 8%, P = 0.03, Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Change in CCI and FIQL Score Results After 6 and 12 Months, With a Univariate Comparison of the Treated and Placebo Groups

| 6 mo | 12 mo | |||||

| Myoblasts (n = 12) | Placebo (n = 12) | P | Myoblasts (n = 12) | Placebo (n = 12) | P | |

| Number of responders | 5 (41.7%) | 6 (50%) | 0.6820 | 7 (58.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.03* |

| n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | |||

| Change in CCI score | −2.5 (−15; 2) | −4 (−10; 6) | 0.6846 | −4.5 (−12; 2) | −2 (−8; 6) | 0.08 |

| FIQL score | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 9 | n = 11 | ||

| Change in lifestyle | 0.3 (−0.5; 2.1) | 0 (−0.4; 1.5) | 0.3853 | 0.7 (−0.3; 2.0) | −0.3 (−1.2; 2.2) | 0.03* |

| Change in coping and behavior | 0.1 (−0.1; 2.3) | 0 (−0.5; 1.6) | 0.3961 | 0.5 (−0.1; 2.0) | 0 (−1.4; 2.2) | 0.10 |

| Change in depression and self-perception | 0.1 (−0.9; 1.5) | −0.1 (−1.0; 1.3) | 0.6232 | 0.4 (−0.3; 1.5) | −0.2 (−1.3; 1.0) | 0.11 |

| Change in embarrassment | 0.2 (−1.0; 2.4) | 0 (−0.3; 2.4) | 0.5330 | 0 (−1.0; 1.7) | 0.3 (−0.4; 2.7) | 0.82 |

Values are expressed as median (range) or number (percent).

The quality-of-life score for each scale ranges from 1 to 4 (1 = poorest and 4 = best quality-of-life), except for the depression/self-perception scale, scored 1 (very poor quality-of-life) to 4.43 (excellent quality-of-life).

*P < 0.05 using the Mann-Whitney test.

CCI indicates Cleveland Clinic Incontinence score; FIQL, fecal incontinence quality of life.

Effect on Secondary Endpoints

Secondary endpoint analysis revealed a lack of improvement in FIQL scores in the placebo arm at both 6- and 12-month evaluations. In contrast, 1 (lifestyle) and 2 (lifestyle, coping/behavior) FIQL components were significantly ameliorated in the AM arm at 6 and 12 months, respectively (Table 2).

None of the anorectal electrophysiology assessments showed significant differences relative to baseline in the AM arm, whereas resting sphincter pressure deteriorated at 12 months in the placebo arm (Supplemental Table 4). Similarly, no change was evidenced on ultrasonography, electrophysiological tests, or MRI at 12 months for both arms (not shown).

Delayed Injection of AM in Patients in the Placebo Arm

After assessment of the 12-month endpoints, the 12 patients who were randomized to the placebo arm were proposed injection of their frozen AM after approval from the independent expert committee. Among them, 11 patients requested delayed therapy, which resulted in a 60% (6/10) response rate at 12 months as compared with baseline in evaluable patients.

Adverse Events

All postoperative hematological and biochemical parameters were normal. Three adverse events were reported, which were imputed to the treatment. None was considered as serious and all were resolved. They consisted in transient pain at the biopsy site (n = 2) and 1 cutaneous infection at the biopsy site that was resolved with antibiotics (n = 1).

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of AM injections for the treatment of FI. Myoblast injection resulted in a significant reduction in CCI scores and improvement in quality of life. Indeed, among patients in the AM arm, the CCI score at 6 and 12 months decreased from a median of 15 at baseline to 9 and 6.5, respectively (Table 2). Analysis of response rates at 12 months showed a >30% reduction in the CCI score in 58% of patients in the AM arm compared with 8% in the placebo arm. For the 7 responder patients in the AM arm, their CCI score dropped dramatically from a median of 12 to 5, respectively, at 6 and 12 months postcell therapy (Fig. 3). These results are in accordance with those of Romaniszyn et al29 who reported a 67% response rate at 12-month follow-up in 9 patients in an open pilot study. An even higher response rate of 100% was reported in another open study by Frudinger et al21 who are currently conducting a placebo-controlled clinical trial in this indication (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu, 2010-021463-32). Nevertheless, in contrast with the latter study, we clearly observed a group of nonresponder patients at 12 months in whom the CCI score remained in the pre-treatment range (Fig. 3).

One unexpected result of this present study was the importance of the placebo effect observed at 6 months. As a consequence, our study failed to demonstrate the superiority of injecting myoblasts over placebo at 6 months. Yet, the decrease in median CCI score was only transient in the placebo arm and CCI scores returned to pre-treatment levels at 12 months, in marked contrast with the AM arm (Fig. 3). In this context, we believe that future clinical trials should consider a primary endpoint at 1 year rather than 6 months. Many randomized trials on FI treatment have evidenced the effectiveness of the intervention per se in FI.27,30,31 However, the placebo effect observed in the present study was more pronounced than that reported in these studies and it remains to be determined whether it was due to the sole bulking effects of the saline and albumin injection or to its association with biofeedback. The latter hypothesis seems unlikely, as no patient responded to biofeedback before inclusion in this study.

Among evaluable patients of the placebo arm who had delayed injection, 6 of 10 were responders at 12 months after having received AM. Among them, 5 of 6 patients had initially been responders to the placebo at 6 months but only 1 of 6 at 12 months. We did not find correlation between response to the placebo at 6 months and response to delayed AM injection at 6 months. Importantly, the efficacy of delayed injection (60% at 12 months) is consistent with that observed in the AM group (58% at 12 months) and frozen cells seem as efficacious as fresh ones. The duration of clinical benefit in responders who received AM injections suggests the in situ differentiation of myoblasts into mature muscle fibers. Such differentiation was demonstrated in our preclinical animal model using injection of green fluorescent protein genetically marked myoblasts in an injured rat sphincter.20 Also, whereas many studies suggest that AM injection leads to cell engraftment, it remains to be formally demonstrated that the newly formed myofibers establish functional connections with nerves as observed in our rat study. Together, the encouraging results of this clinical trial are compatible with a long-lasting, possibly definitive, therapy for FI. The long-term follow-up of these patients will be informative.

Regarding quality of life at 12 months after therapy, the present treatment significantly ameliorated 2 of the 4 FIQL items, that is, lifestyle, as well as coping and behavior. Nevertheless, this benefit appears smaller on FIQL scores than on CCI scores. In this respect, it is of note that 2 responder patients refused to fill out the FIQL questionnaire and to undergo complementary investigation at 12 months. Thus, it is presumable that variations in FIQL and paraclinical data may be somewhat underestimated herein. This contrasts with 2 encouraging previous reports,22,29 but is consistent with the short-term results of the study published by Frudinger et al.21 Our patients were not totally comparable, in terms of age and incontinence severity, with those of previous studies that also reported a positive effect. In our cohort of 12 patients having received AM, 6 (50%) had EAS insufficiency associated with neurological dysfunction and 4 (33%) had associated rupture of the internal sphincter. We cannot exclude that this may have influenced the response rate. Moreover, the heterogeneity of response revealed by this study raises the question of predictive markers of response and/or a more precise definition of indications for cell therapy in FI. In this study, due to limited sample size, no such predictive markers could be identified.

Regarding anorectal manometry and ultrasonography, no change was observed after 1 year of treatment, in accordance with the study by Frudinger et al.21 This study confirms that injection of AM is well tolerated, safe, and provides clinical benefit. Clinically, the only adverse effects observed concerned the muscle biopsy, and these were classified as nonserious and quickly resolved. In parallel to monitoring adverse effects, we performed an extensive analysis of myoblasts for all patients. As expected from previous results in human mesenchymal stromal cells32 or myoblast preparations,28 we evidenced some karyotypic abnormalities, none of which were associated with any growth advantage, as all cell preparations ultimately entered replicative senescence. None exhibited any tumorigenic potential as attested by lack of growth in soft agar culture, an assay in which only transformed cells can proliferate, and lack of molecular anomalies in individual p53 transcripts. It is likely that these erratic genomic abnormalities originated from the cellular stress caused by in vitro manipulation and culture.

Cell therapy may offer several benefits over SNS. It may be appealing to patients not wishing to undergo implantation of an invasive device or to those with cardiac stimulator or defibrillator implants, exposed to MRI, ultrasonic equipment or radiation therapy, or in failure of SNS treatment. On the basis of the present findings, it would be justified to conduct a phase 3 multicenter trial in order to compare AM therapy with SNS with a 12-month primary endpoint and to determine whether injection of AM in the sphincter could become standard treatment for FI.

Together, the results of this phase 2 trial indicate that injection of myoblasts in the striated sphincter of patients with FI provides clinical benefit at 12 months post-treatment, with excellent tolerance and safety. It opens perspectives for the cure of refractory FI.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Nikki Sabourin-Gibbs, Rouen University Hospital, for editing the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

OB and FM designed the original study. AB, JD, and SLC performed myoblast production under the supervision of OB, CG, and JM. SJ was responsible for quality control. PC organized and interpreted karyotypic analyses. DB organized the conservation of frozen myoblasts. FM performed implantation and coordinated patient follow-up. JJT and VB performed some delayed AM injections. AML supervised electrophysiological analyses. EK performed anal ultrasound analyses. JB designed the statistical plan and coordinated randomization. EH and JB performed statistical analyses. OB and VB wrote the initial version of the manuscript, which was edited by JB and FM. All authors contributed to the conception of the work and considered, revised, and approved the final version for submission.

This study was supported by a grant from the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique from the French Ministry of Health and, for a limited part, by Celogos (Paris, France). The work was completely independent. The Ministry of Health and Celogos had no role in the study design, or in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data.

AB was the recipient of a PhD fellowship funded in part by Celogos. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Study Group of Myoblast Therapy for Fecal Incontinence: Patrice Valleur, Luc Sensebé, Rémi Morello, Guillaume Gourcerol, Céline Savoye-Collet, Géraldine Joly-Helas, Christelle Doucet, André Ulmann, Jean-Michel Flaman, Angélique Aublet, Lauriane Vittecoq, Chloé Modzelewski, Delphine Picoche, Noelle Frebourg, Sophie Boyer-Mariotte, Ludovic Lemée, Michèle Nouvellon, Christine Chefson, Lise Gourichon, Arnaud Roucheux, Fabienne Jouen, Julie Lamulle, Laetitia Demoulins, Ingrid Dutot, Sophie Ruault, Fabrice Duparc.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: and the Study Group of Myoblast Therapy for Faecal Incontinence

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharma A, Yuan L, Marshall RJ, et al. Systematic review of the prevalence of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 2016; 103:1589–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasgow SC, Lowry AC. Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 55:482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karoui S, Leroi AM, Koning E, et al. Results of sphincteroplasty in 86 patients with anal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43:813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zutshi M, Tracey TH, Bast J, et al. Ten-year outcome after anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52:1089–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dehli T, Stordahl A, Vatten LJ, et al. Sphincter training or anal injections of dextranomer for treatment of anal incontinence: a randomized trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013; 48:302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerra F, La Torre M, Giuliani G, et al. Long-term evaluation of bulking agents for the treatment of fecal incontinence: clinical outcomes and ultrasound evidence. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda Y, Laurberg S, Norton C. Perianal injectable bulking agents as treatment for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2:CD007959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thin NN, Horrocks EJ, Hotouras A, et al. Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of neuromodulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 2013; 100:1430–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SR, Wadhawan H, Nelson RL. Surgery for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 7:CD001757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cera SM, Wexner SD. Muscle transposition: does it still have a role? Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2005; 18:46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duelund-Jakobsen J, Worsoe J, Lundby L, et al. Management of patients with faecal incontinence. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016; 9:86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams AE, Croft J, Napp V, et al. SaFaRI: sacral nerve stimulation versus the FENIX magnetic sphincter augmentation for adult faecal incontinence: a randomised investigation. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016; 31:465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehur PA, Wyart V, Riche VP. SaFaRI: sacral nerve stimulation versus the Fenix(R) magnetic sphincter augmentation for adult faecal incontinence: a randomised investigation. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016; 31:1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karpati G, Ajdukovic D, Arnold D, et al. Myoblast transfer in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 1993; 34:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremblay JP, Malouin F, Roy R, et al. Results of a triple blind clinical study of myoblast transplantations without immunosuppressive treatment in young boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Transplant 1993; 2:99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menasche P, Alfieri O, Janssens S, et al. The Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation 2008; 117:1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin JT, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:1078–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blaganje M, Lukanovic A. Intrasphincteric autologous myoblast injections with electrical stimulation for stress urinary incontinence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012; 117:164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho CP, Bhatia NN. Development of stem cell therapy for stress urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012; 24:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisson A, Freret M, Drouot L, et al. Restoration of anal sphincter function after myoblast cell therapy in incontinent rats. Cell Transplant 2015; 24:277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frudinger A, Kolle D, Schwaiger W, et al. Muscle-derived cell injection to treat anal incontinence due to obstetric trauma: pilot study with 1 year follow-up. Gut 2010; 59:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frudinger A, Pfeifer J, Paede J, et al. Autologous skeletal-muscle-derived cell injection for anal incontinence due to obstetric trauma: a 5-year follow-up of an initial study of 10 patients. Colorectal Dis 2015; 17:794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36:77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43:9–16. discussion -7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rullier E, Zerbib F, Marrel A, et al. Validation of the French version of the Fecal Incontinence Quality-of-Life (FIQL) scale. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004; 28:562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallas S, Michot F, Faucheron JL, et al. Predictive factors for successful sacral nerve stimulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence: results of trial stimulation in 200 patients. Colorectal Dis 2011; 13:689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leroi AM, Siproudhis L, Etienney I, et al. Transcutaneous electrical tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of fecal incontinence: a randomized trial (CONSORT 1a). Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1888–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bisson A, Le Corre S, Joly-Helas G, et al. Chromosomal instability but lack of transformation in human myoblast preparations. Cell Transplant 2014; 23:1475–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romaniszyn M, Rozwadowska N, Malcher A, et al. Implantation of autologous muscle-derived stem cells in treatment of fecal incontinence: results of an experimental pilot study. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19:685–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel KE, et al. Efficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siproudhis L, Morcet J, Laine F. Elastomer implants in faecal incontinence: a blind, randomized placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25:1125–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarte K, Gaillard J, Lataillade JJ, et al. Clinical-grade production of human mesenchymal stromal cells: occurrence of aneuploidy without transformation. Blood 2010; 115:1549–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.