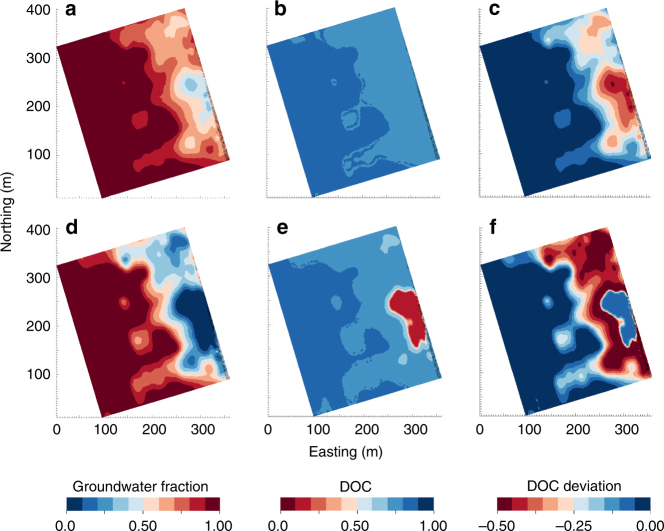

Fig. 5.

Spatial projections based on combining ERT estimates of groundwater fraction with aqueous chemistry. Spatial projections were generated across most of the domain that was sampled using groundwater (GW) wells (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 2,3)34. Due to changes in river stage, the HC experienced a broad range of GW–river water mixing conditions during the sampling period34. Two temporal snapshots were selected that differed in the degree of mixing. a–c Projections during a point in time with modest river intrusion and higher GW fraction. d–f Projections during a point in time with increased river intrusion and lower GW fraction. a, d Projections of GW fraction where pure GW is indicated by 1 and pure river water (RW) is indicated by 0. b, e Projections of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations generated by combining a and d with the empirical relationship shown by the gray line in Fig. 3a; DOC is presented as a fraction of RW DOC concentration, as in Fig. 3a. Between b and e there is a relatively small decrease in the GW fraction (i.e., a small increase in the RW fraction, as shown by comparing a with d). Due to nonlinearity in the relationship between GW fraction and DOC (Fig. 3a), this small decrease in GW fraction led to a large increase in DOC concentrations within the hyporheic corridor (HC). c, f Projections of the DOC mixing model deviations. The projections were generated by combining the spatial projection of GW fraction (a, d) with the empirical relationship shown by the gray line in Fig. 3d. The panels show that a large fraction of river-derived DOC was not transported into the broader HC, but that a small decrease in the GW fraction (increase in RW fraction) resulted in significant quantities of river-derived DOC being transported into the HC